The Levels of Warfare, Part 4: Operational Confusion

Operational art has had a troubled existence in the English-speaking world. Although the concept has existed since the beginning of the 20th century, American officers did not come to it until the 1970s. This was the period of post-Vietnam reorientation toward conventional war with the USSR, which entailed much greater interest in Soviet doctrine. The US Army developed its own operational ideas, and formally adopted the concept of the operational level in its 1982 version of Field Manual 100-5, Operations. From the very beginning, it has stirred controversy.

Level or Art?

Much of the debate has focused on whether it is correct to speak of an operational level or just of operational art. The former was popularized by Edward Luttwak in an influential 1980 paper, two years before its formal adoption into US doctrine. Critics pointed out that the Soviets never spoke of “levels” of warfare, only of “operational art” (although even this is not true1).

Yet Luttwak’s coinage was hardly a radical a departure from earlier usage. Beginning in the 18th century, theorists wrote of tactics and strategy as different parts or branches of warfare, and the Soviets explicitly divided warfare into the tactical, operational, and strategic parts. Describing these as “levels” moreover captures an implicit logic behind the division:

1. Each level is directed to a particular end

From their introduction in the mid-18th century, tactics and strategy were defined in terms of what commanders were trying to accomplish. In their original form, tactics focused on winning the battle and strategy the campaign; in their current incarnations, tactics focus on winning engagements and strategy the war, while operational art focuses on the major operations of a campaign.

2. The levels exist in a hierarchy

Higher levels direct efforts at lower levels; lower levels tell the higher what is possible. This is in line with Nicolai’s 18th-century description of elementary tactics, grand tactics, and strategy as links in a chain (see Part 3). Svechin put it in a similar manner: strategy groups operations for its purposes, operations are combinations of tactical actions.

3. Each level is governed by its own logic

Bourscheid stated this explicitly as early as 1782, when he drew a distinction between tactics and strategy on the basis that they “have two different theories, each of which has its own calculations” (see Part 2). Tactics deal with the immediate problems of applying combat power—the coordination of combined arms. Operations are concerned with large-scale maneuver and give especial emphasis to logistics. Strategy deals with applying all national resources to the war: mobilization, priorities among different fronts, coordinating with allies, etc.

The Fundamental Error

The division of warfare into a three-part paradigm of tactics, operations, and strategy was plain in German and Soviet writing—the Soviets often emphasized this by referring to tactical and strategic art, analogous to operational art. The difference between “level” and “art” is therefore mostly semantic. The real source of controversy is an American invention: defining operational art as the bridge between tactics and strategy.

This innovation was present from the introduction of the operational level in the 1982 version of FM 100-5:

The operational level of war uses available military resources to attain strategic goals within a theater of war.

The 1986 version introduced operational art, which it defined as:

the employment of military forces to attain strategic goals in a theater of war or theater of operations through the design, organization, and conduct of campaigns and major operations.

This is a radical departure from any previous definition of operational art. It was always understood as the role of strategy to make operations serve strategic objectives. Svechin was quite explicit:

The success of an individual operation is not the ultimate goal pursued in conducting military operations however…Strategy is the art of combining preparations for war and the grouping of operations for achieving the goal set by the war for the armed forces.

This is obvious when we make an analogy to tactics. The role of tactics is to win engagements, whether or not those engagements serve any higher purpose or not—a fruitless battle can be brilliantly fought, after all. The purpose of operational art should likewise be to conduct effective operations.

The original concept was frank acknowledgment that individual tactical actions rarely affect the course of the war—operations and campaigns are the true building blocks of strategy. For a recent illustration, we can look to Ukraine’s Kherson offensive: it accomplished the operational objective of pushing the Russians over the Dnieper, but it did not accomplish any strategic objectives on its own.

Roots of the Confusion

Where did this misunderstanding come from? Most likely, it owes to operational art’s mythologized origins. Operational art is often described as something that emerged between tactics and strategy, necessitated by the growing sizes of armies in the 19th century—the Soviets themselves often described it this way.2

Needless to say, this view is wrong. Strategy, as we have seen, originally referred to the operations of a campaign, not to the entire war. Accounts of operational art’s “emergence” invariably take the Napoleonic Wars as their point of analytic departure. This was an anomalous period in which wars were regularly decided by a single campaign, in stark contrast to the preceding centuries in which wars were decided by the cumulative effect of many campaigns in multiple theaters. When Clausewitz’ definition of strategy—the use of tactical actions to accomplish war aims—gained ascendance at the end of the 19th century, German officers resorted to using operativ to fill the conceptual gap.

When American officers first encountered the “operational” in the 1970s, they were not familiar with this history. Assuming that “strategy” had always referred to the highest level of warfare, they attempted to justify the Soviet concept by explaining it as a bridge between tactics and strategy. This definition rapidly caught on throughout the Anglosphere—the British, Australians, and eventually NATO adopted it into their doctrine. The result has been a mess: an overly-broad concept which encroaches on what should properly be called strategy, making no account for the fundamental differences between the two (this flaw was highlighted in the book Alien: How Operational Art Devoured Strategy, by a pair of Australians3).

Operations as Tactics

Interestingly, critics of the operational level often make the opposite accusation: that it is really just tactics on a grand scale.4 This argument hinges on the similarity between the long, continuous fronts of the World Wars and the battleline of a set-piece battle—after all, didn’t the Schlieffen Plan explicitly draw on the Battle of Cannae for inspiration?

This line of argument ignores the reasons for distinguishing between tactics and operations. Let us take the example of a flanking maneuver: a tactical envelopment is effective because it bypasses the bulk of the enemy’s prepared defenses and attacks him from a direction he is not expecting. This is very different from an operational encirclement: although this too might confer some tactical advantages, its main virtue is in cutting off the enemy’s lines of communication, rendering his position untenable.

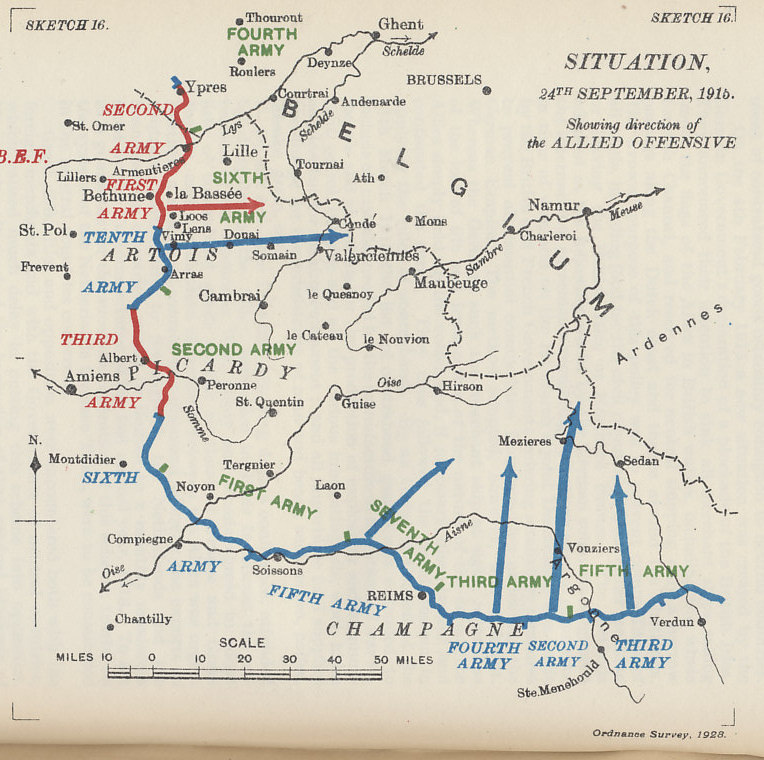

These distinctions are evident in the writings of the French and British during World War I, who used the word “strategy” where the Germans were already using “operational”. Haig, describing plans for the 1915 autumn offensives, writes:

Thus the German salient will be attacked on its two flanks. Looking at the map and trying to apply strategical principles, ‘to get on the Enemy’s rear and cut his communications,’ I argued that the French Army on my right, after reaching Douai, would move on Valenciennes and eastwards on Liege: while the Army from Rheims must advance in the direction Hisson-Namur so as to be able to shatter the Enemy between them.5

It is also important to note that the Germans first drew a distinction between operations and strategy, not tactics (as we saw with Freytag-Loringhoven’s quote in Part 3). Likewise, the Soviets’ Frunze Military Academy created a department of operations out of their department of strategy.

The Philosophical error

In 2011, Huba Wass de Czege, one of the leading authors of the 1982 version of FM 100-5, wrote a mea culpa for his role in the controversy. He identified his use of the term “operational level” as the source of the confusion, claiming it was a misrepresentation of the original Soviet concept (absurdly, he blamed this on his indoctrination on the American way of thinking!). He also maintained that the true purpose of operational art is to serve as the bridge between tactics and strategy—an ahistorical innovation introduced by Wass de Czege himself.

He then proposed his own framework for thinking about operational art. Likening warfare to an explorer’s journey, he compared tactics to how one gets around specific obstacles and strategy to charting the general path forward; operational art mediates between strategic and tactical priorities. This scheme, he argued, holds for all types of armed conflict, even a company or battalion conducting distributed counterinsurgency operations.

This type of excessive abstraction is common in criticisms of the operational level.6 Doctrinal terms developed for state-on-state warfare are turned into generalized concepts for all military operations, even when the underlying dynamics are very different.

The triplet of strategy, operations, and tactics describes patterns unique to large-scale conflicts: belligerents must always mobilize their resources and direct them to the appropriate front; they must coordinate and sustain those forces in offensive or defensive operations; they must figure out how to apply their combat power in direct engagements with the enemy. This holds just as true for Roman legions, feudal hosts, and 18th-century gunpowder armies as it does for modern mechanized forces. Turning these concepts into broad abstractions, applicable to any sort of conflict, strips them of their value.

The “Cognitive Approach”

At the same time as this turn towards abstraction, there was a growing tendency to speak of operational art as a way of thinking. This goes back to Luttwak’s 1980 article, which focused on the absence of operational thinking in the American way of war. He meant something very specific by this: namely, the German and Soviet tendency to focus on attacking the enemy’s rear areas. The emphasis on thought and conception was picked up by Shimon Naveh in his 1997 book In Pursuit of Military Excellence, a postmodern jargon-laden treatise which turned the word “cognitive” into something of a buzzword.

Operational art became inextricably linked with the “cognitive”, leading to its gradual divorce from any specific action. The latest version of Joint Publication 3-0, Joint Operations defines operational art as:

the cognitive approach by commanders and staffs—supported by their skill, knowledge, experience, creativity, and judgment—to develop strategies, campaigns, and operations to organize and employ military forces by integrating ends, ways, and means.

This kitchen-sink non-definition—poor by the standards of freshman-level composition—renders the concept effectively meaningless. Gone is any sense of purpose or scale; to the extent that it says anything at all, it reduces operational art to “planning”.

Conclusion

My purpose in this series on the levels of war has been to show the evolution of the conceptual relationship between tactics and strategy, from antiquity to the present. Although tracing etymologies and shifting semantic senses isn’t the most stimulating task, it helps us to untangle the labels from the concepts. The concepts themselves—stable since the late 18th century—give us firm footing to view the doctrinal debates without getting sucked into the whirlpool of changing terminology.

At its best, doctrine provides a common vocabulary that embeds certain truths about the nature of warfare. It directs attention to the material factors at stake without drawing attention to itself or provoking quibbles over terminological boundaries. It is, of course, debatable how much this is necessary for military success: on the one hand, the US military has proven itself more than capable of conventional operations, while on the other, recent counterinsurgency debacles arguably owe to a failure born of faulty concepts. But whatever the case, if doctrine-writers are going to expend the effort anyway, they might as well do a good job.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

These critics have likely only read the handful of early works which exist in translation, but even in Strategy Svechin wrote, “Wherever operational art has to choose between two operational alternatives, the operator will not find justification for one or the other by staying within the bounds of operational art, but must rise to a strategic level [etazh, as in a storey of a building] of thinking” (Стратегия, p. 19). He and later writers also used the word urovni, meaning levels, to distinguish between tactics, operational art, and strategy.

Georgii Samoilovich Isserson, The Evolution of Operational Art, p. 13.

Alien specifically criticizes how American doctrine makes operational art responsible for campaign design. There is some justice in this: although campaigns were historically the realm of operational art, the enormous campaigns on the Eastern Front of WWII were guided by fundamentally strategic considerations (this is analogous to how “battles” expanded from the tactical realm to the operational—compare Waterloo to Stalingrad). The more straightforward objection in my view is that American doctrine makes strategic objectives the responsibility of operations.

See, for instance, It’s Just Tactics: Why the Operational Level of War is an Unhelpful Fiction and Impedes the Operational Art. The article confuses Jomini’s notion of grand tactics with prototypical “operational” maneuvers. This is incorrect: grand tactics quite clearly means tactics in the modern sense (see Part 2).

Douglas Haig, War Diaries and Letters, 1914-18, p. 144.

For a similar example, see B.A. Friedman On Operations, ch. 6, which is probably the best summation of current arguments against the concept of an operational level.

Excellent final installment, Ben!

Great series. Thanks.