The Fighting March: Operational Mobility During the Crusades

Operational mobility is a universal challenge in war. Enemy action, supply problems, transportation breakdowns all compound one another to make simple things difficult. By the same token, these impediments create an opportunity: whichever side can overcome them gains an enormous advantage over its adversary.

This was just as true in the Middle Ages, a period often stereotyped by sieges and raids, as in other times. It too saw complex campaigns in which mobility was a critical factor. Medieval generals had a good sense for key terrain, and armies often maneuvered around each other for days and weeks, seeking some advantage over their foe or trying to block him from reaching some objective. The most famous battles of the Hundred Years’ War—Crecy, Poitiers, Agincourt—were proceeded by weeks-long pursuits that involved many such moves and countermoves.

The difference from other periods lay more in the texture of the problem. Armies were generally small enough that they could live off the land, and so long as they maintained a certain distance from their foes, could often sustain themselves indefinitely. Their challenges lay more in coordination: a lack of maps, poor roads, and irregular administration made it difficult to synchronize actions across great distances. This was illustrated in 1214, when an English and a German army undertook an ambitious campaign to converge on Paris from opposite directions: one would draw away the defenders, leaving the capital exposed to the other. In the event, the Germans got a late start and the French were able to drive off the English, before turning back to win a major victory at Bouvines.

Competing Systems

This got even more complicated when those feudal armies traveled east during the Crusades. There they encountered an entirely different style of warfare, one built around Turkish cavalry archers and which emphasized mobility. From Saladin the Strategist:

Companies of horsemen danced up to enemy formations on all sides and unleashed arrows before withdrawing a safe distance, often to the protection of a static line of infantry; when pursued, they could turn around in the saddle and continue firing as they fled (the famous Parthian shot, named for another steppe tribe which fought the Romans on the plains of Syria some thousand years before). Only when the enemy was completely worn down or had lost its cohesion would they charge with lances and swords.

This fighting style was completely new to Western armies, which had trouble bringing their heavy cavalry to close quarters with such an elusive foe. It also impeded their operational mobility: cavalry archers harassed marching columns over long distances, wearing down the adversary before he even encountered the main army. But experience is a stern teacher, and the Crusaders eventually worked out a technique that allowed them to move great distances in the face of this threat, allowing them to undertake more ambitious campaigns.

Early Decades

Despite these challenges, the Crusaders had spectacular early success. After the fall of Jerusalem in 1099 they managed to win a string of victories that expanded their hold in the Levant, and they ultimately established four states: the Principality of Antioch, County of Tripoli, Kingdom of Jerusalem from north to south along the coast, and the County of Edessa stretching northeast across northern Syria and Mesopotamia.

These early victories depended in no small part on tactical innovation. Already in 1099, just weeks the capture of Jerusalem, they marched out across open country to meet a large Egyptian army, formed up in a 3x3 grid of mixed infantry-cavalry battalions, ready to meet the enemy from any direction. Over time, they also adopted cavalry archers in their own armies, recruiting local-born warriors and equipping mounted sergeants with bows. Although these could not compare with Turkish archers in quality, they helped offset their disadvantage.

They also depended heavily on fortresses. The land was already dotted with strong castles, but the Crusaders expanded these and built new ones to cement their rule. These proved useful when facing invasions, as it gave the Christian army plenty of safe havens to shelter in while seeking a favorable engagement. What is more, major Muslim offensives drew warriors from all over the region hoping to gain booty, so castle walls could be used to gather in provisions, and their garrisons could fall upon unsuspecting raiding detachments. Conversely, frontier castles also served as useful bases from which the Crusaders could launch raids of their own.

Finally, the Crusaders benefitted from the region’s fragmented political map. The great emirs of Damascus, Aleppo, and Mosul were all nominally under Seljuk authority, but in practice maintained a large degree of autonomy. They did collaborate in a number of campaigns, but their motives varied and they suffered from the weaknesses inherent to all coalitions.

The Crusaders’ fortunes began to shift in the 1130s, when a fearsome warlord named Zengi began subduing the fractious princes of Syria and upper Mesopotamia. It was not long before he turned this growing strength against the Crusaders. Zengi’s first great triumph came in 1144 when he captured the city of Edessa and half the County’s territory. Over the next two decades, he and his son Nur ad-Din pried away one Crusader possession after another, leaving them mostly confined to a strip of land along the coast.

The Zengid dynasty was also very successful in open battle, inflicting a number of harsh defeats on the Crusaders which left them scrambling for a tactical solution. For this, they could look to the other great military system in the region: the Byzantines.

The Eastern Frontier

By the time the Crusaders first set foot in the Holy Land, the Byzantines had been fighting Arab and then Turkish armies for nearly half a millennium. Since the 630s, they had dealt with continuous waves of invasion on their eastern frontier, devising many techniques for dealing with them.

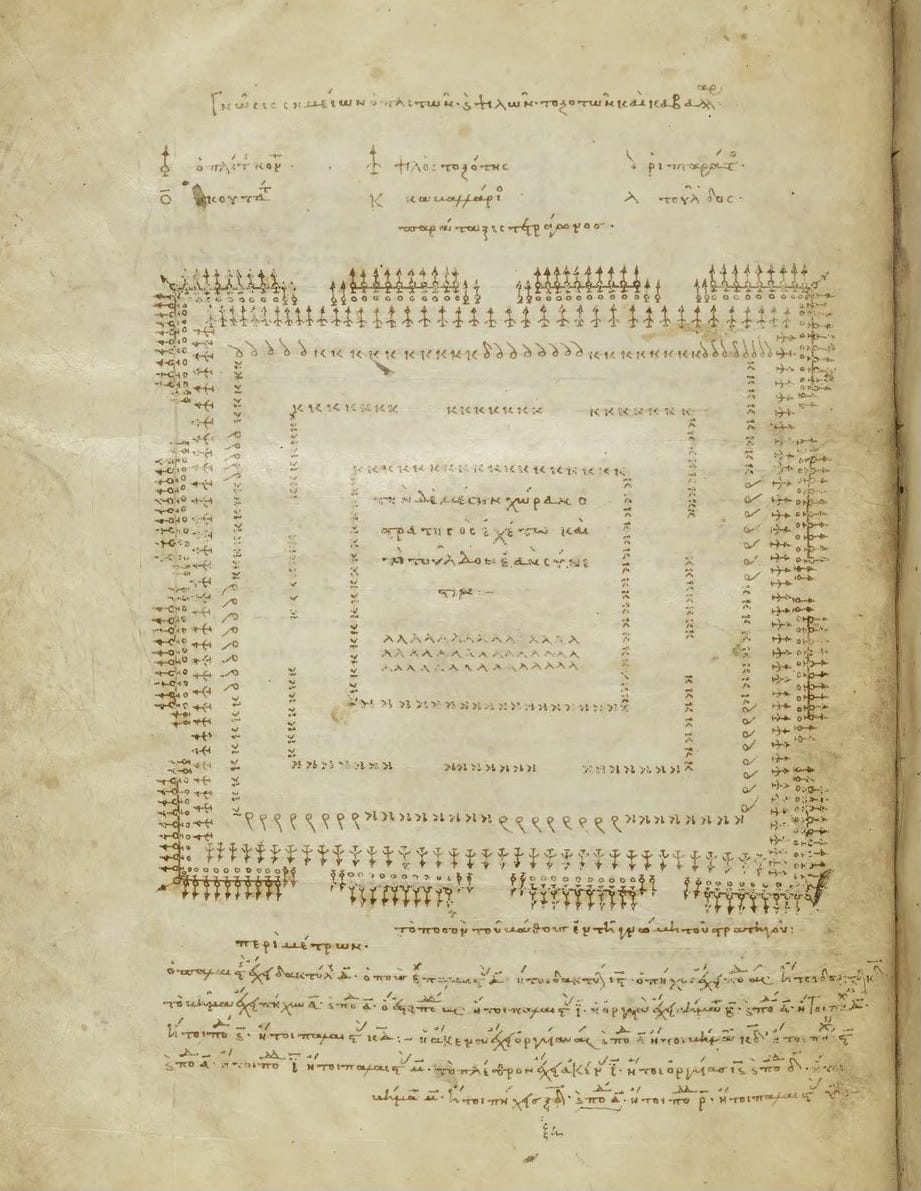

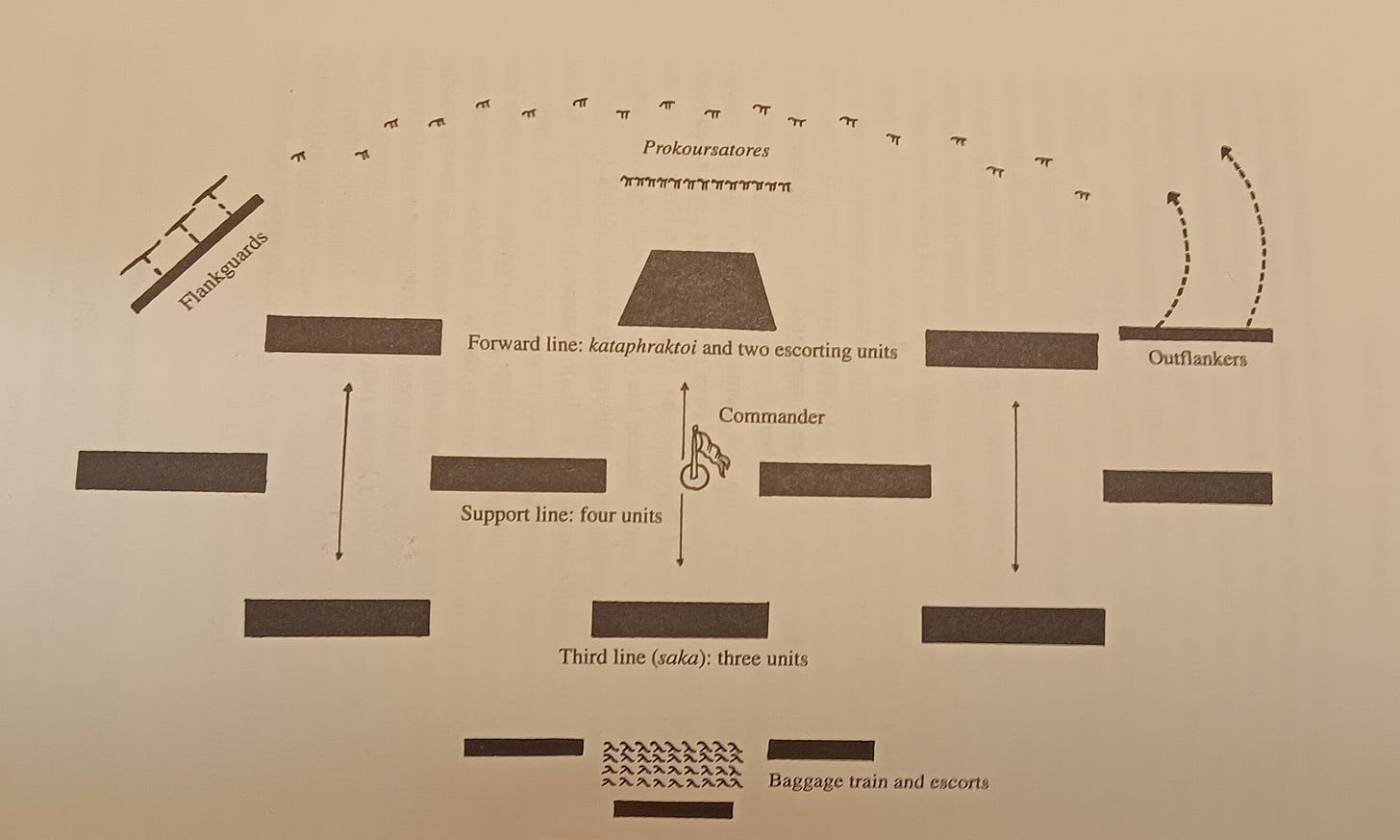

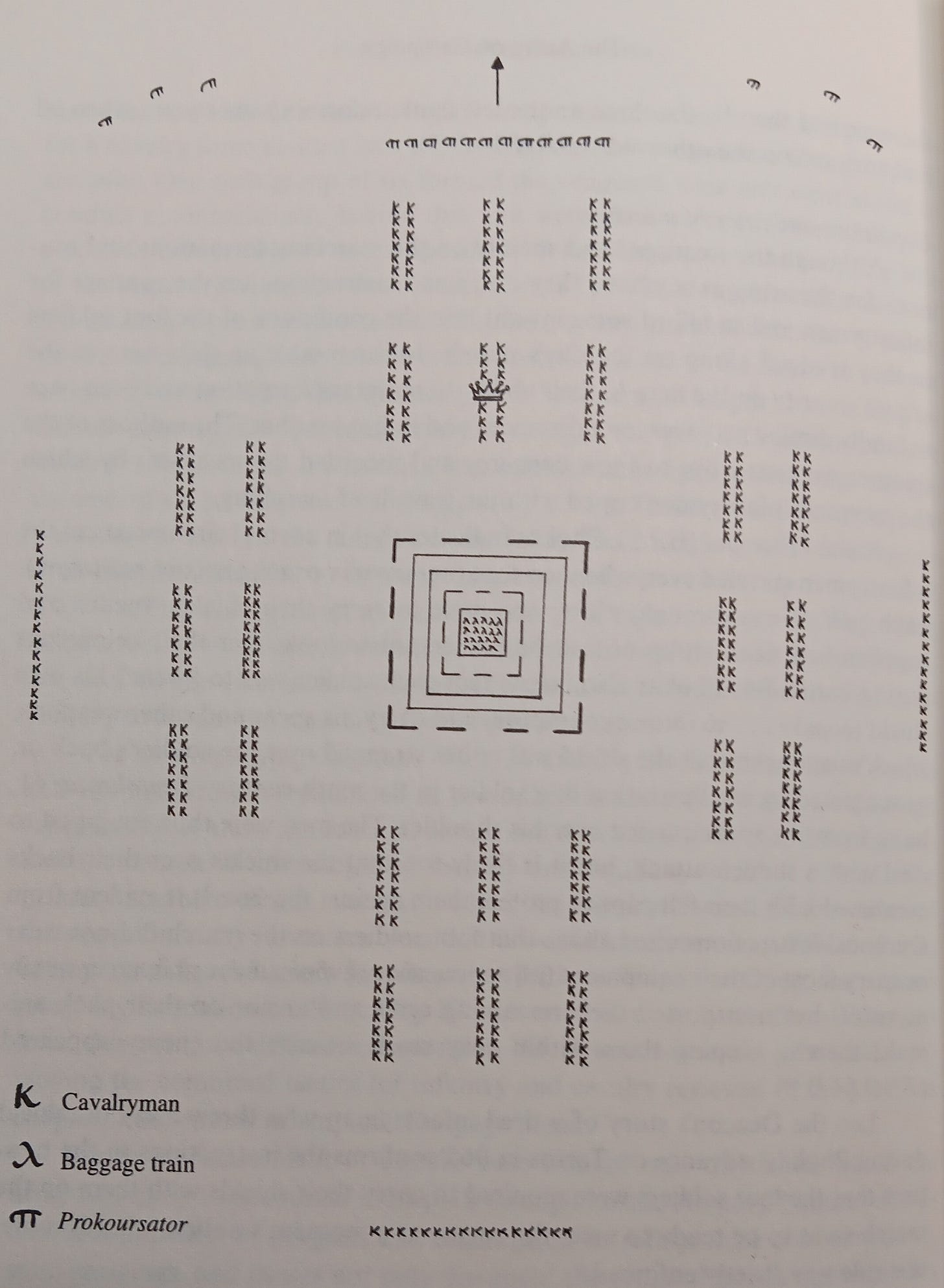

In the first place, the cavalry followed the old Roman practice of fighting in multiple lines—two at a minimum, plus a baggage guard. This was ideal for fighting light cavalry, as the supporting line could beat back any envelopment of the first.

They employed their infantry in an altogether different scheme. Foot soldiers were formed into a large hollow square, protecting the baggage and any civilians that might be accompanying the army. Spearmen were placed in the front ranks to repel any charges, and archers behind them fired overhead. There were also regular gaps in the line, defended by javeliners, which allowed cavalry to pass through. Normally the cavalry would fight outside the square in multiple lines, but when hard-pressed or facing a much larger force, could retreat to safety.

When marching through hostile terrain, the Byzantines adopted a variation of these formations. The infantry marched in its square formation, protecting the baggage, while the cavalry rode in columns to the front, rear, and along either flank. This allowed them to form up quickly if the enemy appeared in front and to respond immediately to ambushes from either side (useful while passing through the defiles of Anatolia and the Balkans). The four blocs of cavalry could also provide mutual support, and in the event of a reverse retreat inside the infantry square.

Adaptation

From the beginning, the Byzantines exerted a strong influence on the Crusaders. They provided guides to the First Crusade as it crossed the dangerous Anatolian highlands, where their tactical advice staved off disaster. During the 1130s to 1160s, Byzantine armies also participated in many combined operations with the Crusaders in Egypt and Syria.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.