Operational Maneuver and Psychology

Since the earliest days of organized warfare, the appearance of the enemy on the flanks or rear has often been enough to destroy entire armies. Once a few individuals or units are overcome with panic and flee, their more stouthearted comrades are left with exposed flanks; some of these may then flee in turn, creating a cascading breakdown of cohesion and morale as the army’s position becomes less tenable. Or, as more often happens, an army routs from the rear, leaving the forward echelons feeling exposed. Discipline and training can mitigate this, but so long as a threat from the rear is credible, it exerts tremendous psychological pressure.

It is a core tenet of maneuver theory that operations should attack the enemy mentally as well as physically. Taken in its most extreme Boydian form, the essence of maneuver is the progressive discombobulation of the enemy’s ability to interpret events. But how well does that hold up at larger scales? Modern armies do not fight on a single battlefield, but across extended fronts—does operational maneuver create the same effect? The 20th century witnessed several such maneuvers employed to decisive effect: it is worth looking at a few of them in detail.

1. Fall Gelb

The Allies’ plan for 1940 was straightforward. They expected a German offensive through Belgium, as had happened in 1914, so they prepared for First Army Group to advance into Belgium while Second and Third manned the Maginot Line along the eastern half of the front. Backing these forces was a strong general reserve stationed near Reims, including the French Seventh Army, which possessed a light armored division and two motorized infantry divisions.

Toward the end of 1939, the Allies’ Supreme War Council grew increasingly concerned that the Germans would also pass through the Netherlands, and made contingencies to link up with the Dutch on their left flank. Seventh Army was chosen for this role, as its motorized units could cover the longer distance—this meant taking it out of the reserve and putting it on the far left flank of the line.

When German Army Group B crossed the Belgian border on 10 May, it seemingly confirmed the Supreme War Council’s suspicions. Anglo-French forces moved up into Belgium the following day, with the Seventh Army on the far left flank. Initial engagements on the 12th went favorably for them, convincing the high command that they had judged correctly, but that evening German Army Group A approached the Meuse at three points, near Dinant, Monthermé, and Sedan.

On 13 May the Luftwaffe shifted its main effort to Sedan, defended by Second Army, devoting well over half its operational aircraft. For eight hours, they unleashed a terrific bombardment on just a few kilometers of the front manned by a single infantry division. The infantry regiments of three Panzer divisions began their crossing immediately after, knocking out bunkers one by one. The Panzers themselves crossed the following morning. Second Army threw in its reserves, but confusion compounded the slowness of a rigid command structure so that the counterattack was delayed and piecemeal. The Germans were able to push past these and secure their bridgehead. 60 km to the north, a similar scene transpired at Dinant.

The French still possessed three armored divisions in general reserve and were beginning to stand up a fourth. 1st Armored Division had already been sent up into Belgium and had to be desperately recalled. As it returned south on the 15th, short on fuel from all its movements and strung out along the roads, it was destroyed by two Panzer divisions which had broken out from Dinant, aided by heavy Luftwaffe bombardment. 2nd Armored Division’s tanks were loaded onto rail flatcars toward Belgium while its wheeled vehicles traveled separately by road, leaving the division unable to reconsolidate before being overwhelmed by the German offensive. Only 3rd Armored Division was sent south of Sedan, where a fierce battle was developing. It and other elements of the general reserve were committed as fast as they could be moved up, but they were outnumbered two-to-one; after a vicious three-day battle, they were finally repulsed on the evening of 17 May. A desperate attempt to cut off the penetration with the hastily-assembled and incomplete 4th Armored Division also failed on the 19th, leaving the route to the coast clear.

The offensive had a psychological impact both on the frontline troops and leadership at all levels. The ferocity and suddenness of the attack on Sedan took the defenders completely off guard. This area was defended by Series B reservists, meaning mostly older (above 30) and not expecting to see serious combat in the first place—their fortifications were not even complete. It was above all the intensity of the aerial bombardment that unnerved them: although the attack inflicted minimal casualties, it severely rattled the defenders and cut their telephone lines to the rear. False reports that Panzers had overrun their positions caused many rear-echelon troops to panic and flee on the evening of the 13th, including much of the artillery. Most of the forward elements continued to resist until German armor did cross the following morning.

The leadership’s shock was slower to take hold. After discounting reports of German units moving through the Ardennes, they were completely stunned by the main attack—when news arrived on the 14th that the division in front of Sedan had already routed, the theater commander collapsed in tears. Although they did throw everything they had into the gap, a slow and inefficient command process delayed what might otherwise have been an effective response. Once this failed, they were left without much left to work with, and seemed to lose their initiative. This malaise extended to First Army Group leadership. Once the full extent of the catastrophe became apparent after 15 May, its leaders became extremely demoralized and hesitant to attack the emerging salient, where quick and decisive action might have severed the armored spearhead as it hurtled toward the coast.

However, two things must be said against this. Despite being trapped in a rapidly deteriorating situation, First Army Group never lost its cohesion. It kept up the fight against Army Group B in Belgium and, when ordered to retreat on 23 May, conducted a fighting withdrawal in good order and continued resisting all the way through Dunkirk. Secondly, speculation about a counterattack must also be tempered by the harsh reality that its more mobile units were poorly disposed to respond, that they were still engaged with Army Group B, and that the Luftwaffe had managed to defeat every Allied counterthrust thus far.

The psychological impact of the German offensive was thus most acute during the breakthrough itself, not during the ensuing envelopment. Although the effects of this initial shock persisted in the following weeks, as the general staff and army commanders acted with inexplicable lassitude, that cannot be separated from the fundamentally bad posture in which they began the campaign. Seventh Army had been placed on extreme left long before the invasion began, while two armored divisions were prematurely committed to Belgium, leaving little margin to respond to any surprise. It was an error in initial dispositions which even the best commanders would struggle to recover from.

2. The Frontier Battles in Russia

If the French were surprised by the direction of the German attack in 1940, the Soviets in 1941 were surprised by the entire offensive. When three German army groups crossed the border on 22 June, the Red Army was already in disarray. Formations lacked sufficient stockpiles of ammunition and fuel, their vehicles were in a poor state of repair, and did not have proper orders to respond to an invasion—units along the border were even told not to respond to provocations.

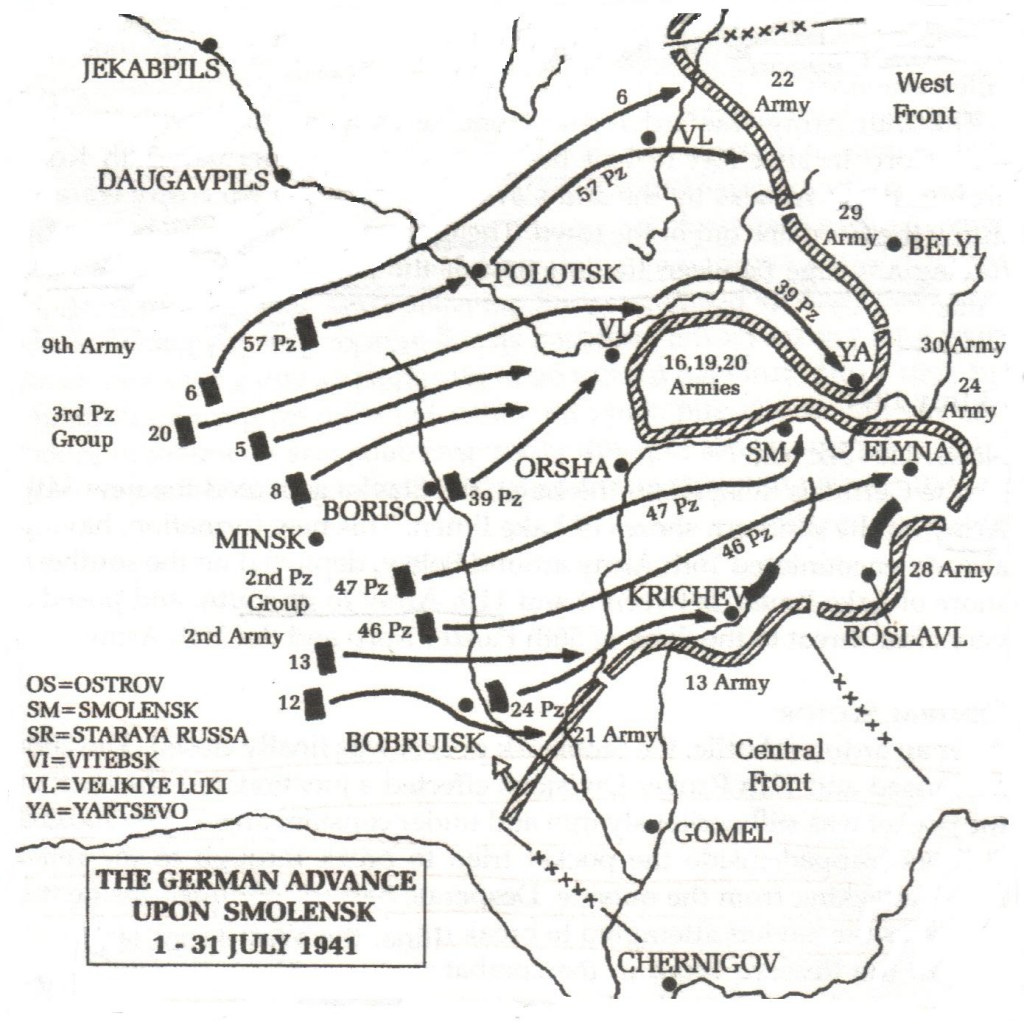

The vastness of the Soviet frontier was so great that no single maneuver could threaten the integrity of its entire defense, but could destroy large operational groupings in a stroke. The German main effort was Army Group Center, which faced four armies and two mechanized corps in Belorussia. The Luftwaffe destroyed most Soviet aircraft on the ground as two Panzer groups swung around in a vast double envelopment to meet at Minsk, over 300 km beyond the border. German aircraft continued to pound Soviet artillery, groupings of vehicles, and command posts, degrading not only their physical ability to resist, but also telephone links between echelons.

This last bit was crucial. Most units were left completely in the dark and could not coordinate a response, nor did they receive orders to withdraw once the scale of the disaster became clear. Several undertook counterattacks on their own initiative, but these completely failed in the face of superior air and ground forces. Left to their own devices, hundreds of thousands of soldiers managed to escape the thin cordon by abandoning all their equipment. Nevertheless, it took Army Group Center over a week to reduce the pocket after it was closed.

This stands in contrast to the subsequent envelopment battle, in which the Stavka maintained communications with subordinate commanders throughout. As Fourth and Ninth Armies were liquidating the Minsk pocket, Second and Third Panzer Groups raced ahead to entrap a second defensive line forming along the Western Dvina and Dnieper. The armies of this line put up futile resistance as their commands were overpowered, but they managed to hold open a corridor into the pocket for nearly three weeks after the operation began. Once the pocket was closed, the cordon was held more tightly and fewer Soviets managed to escape; but as at Minsk, the surrounded armies continued to resist long after.

Operationally speaking, the deep German penetrations caused neither a psychological nor moral breakdown. Initial Soviet dispositions in the early weeks of the campaign made their responses inadequate, but only the physical destruction of communications equipment truly discombobulated them. Where breakdowns did occur, they were at a much smaller scale. Even before the two pincers had closed around Smolensk, the Germans attempted penetrations at several other points along the line; as at Sedan, these caused units to rout—in one case, three infantry divisions fled at the mere approach of a single Panzer division. Timoshenko, the Western Front commander, recognized that this was an essentially tactical problem. He ordered troops and villages in the rear areas to fortify their positions and counterattack against any spearheads, which he was confident would scatter them. The real concern was not that a breakthrough could cause a general panic, but that localized panics could allow breakthroughs.

3. Inchon Landings

The examples from World War II show the impact of operational envelopments on the offense, but the Korean War furnishes an example on the defense. On 25 June 1950, North Korea launched a major offensive that quickly overwhelmed South Korean and US forces along the 38th Parallel. In little over a month, the Korean People’s Army (KPA) drove the defenders back to small area around the southern port of Pusan. There was intense fighting over the next several weeks as the US scrambled to shore up the perimeter with reinforcements from Japan and allied forces under a UN mandate.

As the front stabilized, commander-in-chief Douglas MacArthur began planning an amphibious assault that would cut KPA supply lines and render their position in South Korea untenable. His target was the port of Inchon, a short distance from Seoul, which would allow UN forces to retake the capital and claim a major moral victory. Two US divisions and two South Korean regiments were detached from Eighth Army and formed into X Corps for the purpose. The plan was for two US Marine regiments to assault the beaches, after which the entire corps would move on Seoul.

On 31 August, the North Koreans launched the Naktong Offensive, a renewed attack on the Pusan Perimeter. Although the fighting was intense, UN lines held, and MacArthur decided that he could spare the forces to launch his planned landings on 15 September. X Corps found the beaches at Inchon surprisingly weakly defended, and a week later arrived at Seoul, into which the North Koreans had managed to throw only a single understrength division.

The day after the landings, Eighth Army began its counteroffensive from the Pusan Perimeter. The North Koreans were still attacking, and UN forces ran right into them, making only localized progress for the first three days. KPA divisional headquarter began withdrawing on the night of 18-19 September, and the following day American and ROK units made their first substantial breakthroughs. As X Corps battled for Seoul in the north, Eight Army pressed the pursuit to the 38th Parallel.

Interrogations of North Korean prisoners taken in the first few days of the counteroffensive revealed they had no knowledge of the landings at Inchon, suggesting that their high command concealed the news to prevent a rout. At first glance, this seems to support the maneuverist view: the North Korean high command feared that their men would collapse if they learned the true situation, so they were kept ignorant until a retreat could be organized.

A closer look reveals a different picture. By the time the Naktong Offensive began, North Korean forces had already been engaged in two months of hard fighting, including a full month along the Pusan Perimeter itself. UN forces already outnumbered them and continued to receive large reinforcements in September, while enjoying artillery dominance and absolute air superiority. Interviews with POWs revealed that most of the soldiers were unwilling conscripts, already demoralized and only fighting under threat of death. The Naktong Offensive was a last desperate push by the North Korean high command, in other words, and it had already been soundly defeated by the time the first boots hit the beaches at Inchon.

We do not have any record of the KPA high command’s decision-making at this time, but when it finally did decide to pull back, it was only acknowledging the reality of defeat, much as First Army Group did in May 1940. The withdrawal began in good order, with stiff rearguard actions holding back the Eighth Army, but KPA divisions began to dissolve under constant aerial bombardment and relentless pursuit over the next two weeks. Even then, roughly half the North Korean troops and nearly the entire leadership cadre escaped north of the 38th Parallel (the highest-ranking officer to be taken prisoner, 13th Division’s chief of staff, was a deserter).

Two points stand out. The first is that the KPA was defeated by Eighth Army alone. Although the landings probably spared UN forces by persuading the North Korean high command to withdraw sooner than they otherwise would have, the Naktong Offensive had already culminated. The commander of South Korea’s 1st Division assessed that North Korean attacks had already reached their highwater mark in the first week of September,1 while others judged the offensive to have been conclusively defeated by 12 September.2

The second is that the landings failed to achieve the fullest measure of success because they did not aim at cutting off the retreating KPA forces. MacArthur focused his immediate efforts on recapturing Seoul by 25 September, a symbolic three months after the war began (although the actual fighting continued for several more days). This allowed the remnants of the North Korean army to escape up the eastern side of the peninsula. The emphasis on the moral and psychological objectives of the Inchon Landings, at the expense of the physical, prevented the success from being total.

4. Crossing the Suez Canal

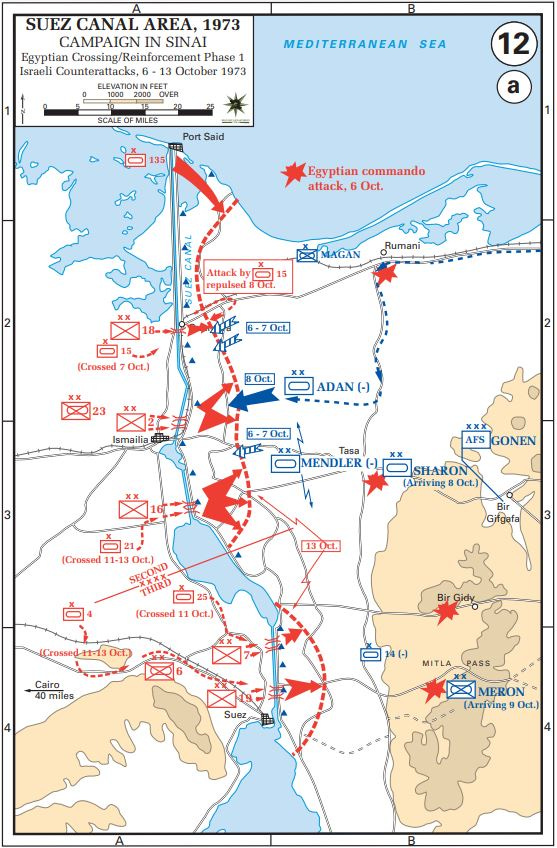

The 1973 Arab-Israeli War provides us another notable example of an operational envelopment on the defense. On 6 October 1973, Syria and Egypt launched a surprise attack on Israel to recover the territories they had lost in the last war: the Syrians on the Golan Heights, the Egyptians on the Sinai. The Egyptian offensive was the more impressive—and difficult—of the two. Commandos crossed the Suez Canal in small boats and neutralized the border forts while engineers laid bridges. Two field armies then crossed and dug in on the eastern bank: Second Army along the northern half, Third Army along the southern.

Like the French of 1940, the Israeli Southern Command was in a state of shock for several days. Not knowing what else to do, they ordered a series of ineffectual frontal attacks with the tank division they had on hand, incurring heavy losses against teams of infantry equipped with antitank rockets. Unlike the Germans of 1940, however, the Egyptians were not aiming for a rapid exploitation. They were under strict orders to remain inside their SAM umbrella, which would protect them from the formidable Israeli Air Force—it was a bite-and-hold operation on a grand scale, not a sweeping offensive.

Over the following days, the Israelis regained their bearings and poured reinforcements into theater. Once the Syrian front was stabilized, more were diverted south. The Israeli plan for the counteroffensive was to push their armored divisions across the Suez Canal at the gap between Second and Third Armies and cut them off from behind. The Egyptians had some sense of Israeli intentions and sent tank forces to attack the assembly area, but these thrusts were poorly organized and easily defeated.

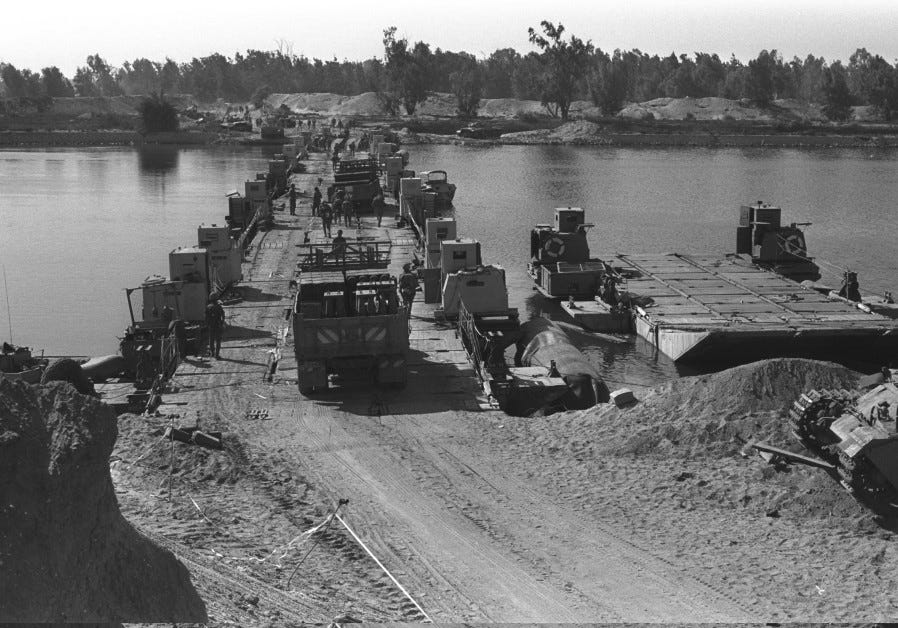

On the night of 15-16 October, Israeli paratroopers secured the western bank of the canal. A tank brigade was ferried across the next morning, while engineers began laying bridges for follow-on forces. The tanks began attacking Egyptian SAMs to open a seam in the air defenses, allowing Israeli planes to get in and start prosecuting ground targets. The Egyptians were soon alerted of the bridges and bombarded them with airstrikes and artillery, but all three Israeli divisions managed to get across in the next few days.

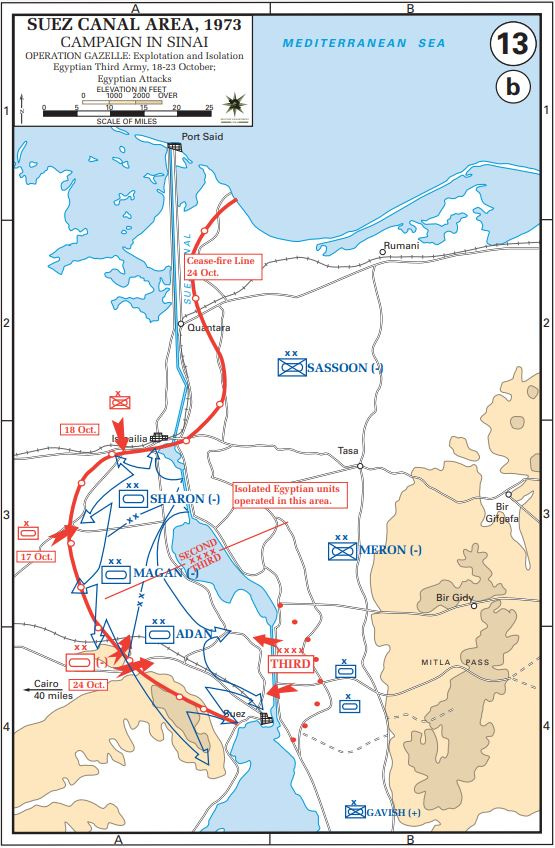

By this point, however, the great powers were pushing for a ceasefire. The Soviet Union was worried about a major defeat for its Arab clients. The Israelis had thoroughly beaten the Syrians on the Golan and were driving toward Damascus; the impending encirclement of Third Army and destruction of their SAM sites could spell catastrophe. The US, for its part, wanted to avoid an escalation in tensions. Both Egypt and Israel agreed to a ceasefire to go into effect on 22 October along existing lines, but their forces were hopelessly intermingled and soon began fighting again. A new ceasefire was agreed for the morning of 24 October, by which time the Israelis reached Suez City, completely sealing off Third Army.

Egyptian actions in the days leading up to the ceasefire gives us an interesting picture of the psychological and moral impact of the crossing. Chief-of-staff General Shazly realized the extent of the Israeli incursion on 19 October and advocated pulling four brigades back across the canal to confront the enemy penetration. President Sadat’s reason for refusing is interesting: he feared a repeat of the 1967 war, when routing units inspired a mass panic among the Egyptians. Pulling units west of the canal—even for sound operational reasons—might cause the rest of Third Army to give way. Although this decision would have undoubtedly led to Third Army’s destruction had there been no ceasefire, Egyptian forces maintained their coherence to the end. Infantry on the west bank of the canal continued to stoutly resist as the Israelis closed the pocket around them, while the Third Army on the east bank was not panicked by events to their rear.

The Psychology of Envelopment

Taken together, these case studies show how true panic is born of proximity. Unprepared French and Soviet soldiers surprised by Panzers, North Koreans subjected to constant air strikes while dogged by pursuing troops, or Egyptians anxiously watching their comrades slip back across the canal—it is the primal sense of immediate danger that seizes hold of men’s mind. Nothing like that appears in great operational cauldrons, where the threat is purely intellectual and far off. So long as the immediate flanks are secure and the leadership intact, encircled troops almost always hold together.

This is also very different from the psychological shock that affects operational decision-making. The French, Soviet, and Israeli high commands all experienced moments of stupor, leaving them temporarily unable to respond to the crisis of the moment. This was the result of surprise, however, something that can only be created at great effort and which quickly dissipates. All three high commands recovered their perception of events within days, and although they each had very different outcomes, that was a result of widely differing material positions. And if lingering shock did in fact contribute to ultimate defeat in the French case, that only goes to show that the psychological is a handmaiden to the physical.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Please like and share if you enjoyed, it helps more people find this. You can also support with a paid subscription, supporters receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529 and get access to exclusive pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.

From Pusan to Panmunjom, p. 30.

A lot of these are about C3 networks. The French one in 1940 was deeply shaky and was disrupted both at the tactical and operational level while the German one was excellent. There's an interesting underresearched thing there - why did the BEF have all the No.19 radios it needed and the French were reliant on a civilian phone net that was shit until a massive state development programme as late as the 1970s? Similarly, the Matilda IIs and Valentines that went to Moscow in 1941 were all fitted with either 19 or both 19 and the rearlink whose number I've forgotten in a radio-poor Soviet army.

Brilliant.

Always have reserves.