Crowning the King of Battle: Field Artillery in the Italian Wars

This piece focuses on several key battles during the Italian Wars. For more on the broader tactical developments and general history of the period, I recommend Frederick Taylor’s The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, which paid Dispatch subscribers receive free.

Beginning around the year 1500, Europe underwent two distinct military revolutions. The first was the ascendance of infantry formations that combined the staying power of Swiss pike battalions with the offensive power of new handheld gunpowder weapons. Pike-and-shot warfare, as this was called, dominated battlefields for the next two centuries. The second was precipitated by the proliferation of high-quality siege cannons. These sparked an evolutionary race between the offense and defense, resulting in the distinctive star-shaped fortresses and new siege techniques.

These twin shifts were birthed in the hothouse of the Italian Wars, in which French, Spanish, and Imperial armies descended on Italy in a series of conflicts from 1494 to 1559. A combination of new weapons, sustained warfare, and increasing military budgets forced intense experimentation and innovation. By the mid-16th century these new tactics were firmly entrenched, even if they continued to be refined over the following decades.

At the juncture of these developments stood a third, less celebrated revolution: the integration of artillery into field armies. Cannons first appeared on European battlefields in the early 14th century, and were used in pitched battles by the mid-15th. These early pieces were neither easy to use nor especially accurate, and their overall effect on battles is open to debate. In the following century, Italy served as an important incubator for artillery tactics. It was the battlefield of Western Europe for the first third of the 16th century, during which time new guns proliferated in unprecedented variety and quantity. By the end of the Italian Wars, field guns were still nowhere as decisive as the new infantry or siege tactics—it would be nearly a century before they became truly dominant—but they had become an essential part of any field army.

As such, the period provides an interesting look at how armies experimented with an immature technology. In contrast to modern artillery doctrine, which was worked out within the span of World War I, it took generals many decades to figure out how to use direct-fire cannons effectively. Not only was the technology itself continuously evolving, but so too was the broader tactical landscape in which it was employed: infantry and cavalry were themselves undergoing great changes, making the lessons from individual battles far more ambiguous.

An apt comparison can be made to contemporary UAV employment. Not only are the drones flown in Ukraine today more advanced than the ones used in Nagorno-Karabakh and Syria, but the scale and complexity of operations is also far greater—affecting how they are used. Future conflicts will see still more advanced models, yet will not necessarily face the same saturation of air defenses or EW that exists in the Donbas, with inevitable doctrinal consequences. The mutual evolution of air, ground, missile, and electronic arms makes the future obscure. In the face of such uncertainty, we find echoes of the long wars between the Valois kings of France and the Habsburg monarchies.

Gunpowder Enters the Stage

The first period of artillery development in Europe was the opening phase of the Hundred Years’ War, when both France and England used siege cannons with mixed results. Demand spurred innovation, however, and their quality steadily improved. The French invested especially heavily in the last decades of the war under the direction of the brothers Gaspard and Jean Bureau, who developed better casting techniques and amassed a large artillery park of improved weapons. With these guns in tow, the French army swept through Normandy between 1449 and 1450, reducing a number of English-held fortresses.

The last years of the war also saw new roles for artillery. The great siege weapons were bombards and mortars cast from iron, which fired massive stone balls. Smaller weapons, such as bronze culverins, often had much longer barrels but fired balls less than 10 kg in weight. These were used to punch through high castle walls, but could also be used against troops in the field. At Formigny in 1450, the outnumbered French pushed two culverins forward to fire against the English from outside the range of their longbowmen. This apparently inflicted modest casualties, but not enough to prevent the opposing infantry from rushing forward and capturing the unprotected guns. The guns’ report had in the meantime alerted a nearby detachment of French cavalry which rushed to the field of battle, where it not only equalized the balance of forces but was able to ride over their dispersed infantry.

A more effective use of artillery was found at Castillon in 1453, the final battle of the Hundred Years’ War. The English were trying to head off an invasion of Gascony, the last of their major possessions in France, and launched a desperate attack against a strong French position containing hundreds of gunpowder weapons and surrounded by strong fieldworks on all sides. Masses of shot ripped through the closely-packed English ranks, and those that made it to the ramparts were cut down by the defending infantry; a well-timed cavalry charge on their flanks sealed the French victory. Although it is possible that the artillery caused most of the casualties at Castillon, its real role was disrupting the English columns at the point of attack.

Innovation and Proliferation

Formigny and Castillon showed that artillery could play a major role in open battle, but it was not yet clear what that was. Its effect at Formigny was indirect, while the casualties it inflicted at Castillon depended on the enemy’s willing to frontally assault an extensively-prepared position. There was as yet no reliable way a general could put his cannons to good use.

Manufacturing techniques meanwhile continued to improve in the following decades, with lighter cannons and carriages that made guns more maneuverable in battle. During this time, the dukes of Burgundy—the semi-independent vassals of the French Crown—developed a powerful artillery arm of their own, which they used in wars against their sovereign and the Swiss Confederacy. Here too, the effectiveness of field artillery was ambiguous.

The Battle of Montlhéry, fought between France and Burgundy in 1465, typified the use of artillery in the later 15th century. Both sides brought cannons, but Duke Charles the Bold had them in much greater numbers. The initial bombardment inflicted some casualties and spurred the French knights into action. The rest of the battle was a cavalry and infantry engagement, although the Burgundians kept up the cannonade on the rear lines throughout. It is impossible to say precisely how much of a role the artillery played at Montlhéry, but it was a decidedly subordinate role in what was otherwise a typical late-medieval battle.

More interesting was his war with the Swiss in the 1470s. In three pitched battles, he fought not against a robust cavalry-centric army but large squares of pikemen—ideal for use against Charles’ knights, but also vulnerable targets for his cannons. In the first of these, at Grandson, a Swiss column charged as he was deploying his army and overran his artillery before it could have any effect. His next two defeats owed as much to maneuver as to speed: on both occasions, the Burgundians formed up in a strong position protected by artillery, but the Swiss outflanked these and managed to entrap the entire army. All three were heavy defeats for the Burgundians, the last of which was fatal for Charles.

The Duke’s losses to the Swiss owed more to larger tactical mistakes than anything else, but they illustrate the problems of artillery in open-field battle. It was difficult to deploy them rapidly enough to be effective, but it was also hard to bait the enemy into battle against a prepared position. Great gunpowder victories like Castillon appeared to depend more on enemy recklessness than anything.

Major battles featuring large numbers of guns were few and far between for the rest of the century, but the new weapons were in high demand. France (including Burgundy) remained the most advanced manufacturer, although its guns and casting techniques rapidly proliferated to other parts of Europe. Already by the 1480s, Ferrara—an important French ally in the later Italian Wars—was a major center of production and innovation.

One last innovation of the 15th century was in operational mobility. During the reconquest of Normandy in the final years of the Hundred Years’ War, taking one stronghold after another in quick succession, the French siege train only had to march a short distance from Paris, and often could rely on the Seine for transport. But French artillerists continued to make gun carts and carriages stronger and lighter, and the monarchy invested in teams of draft horses to pull them vast distances.

Charles VIII’s Invasion and the Battle of Fornovo

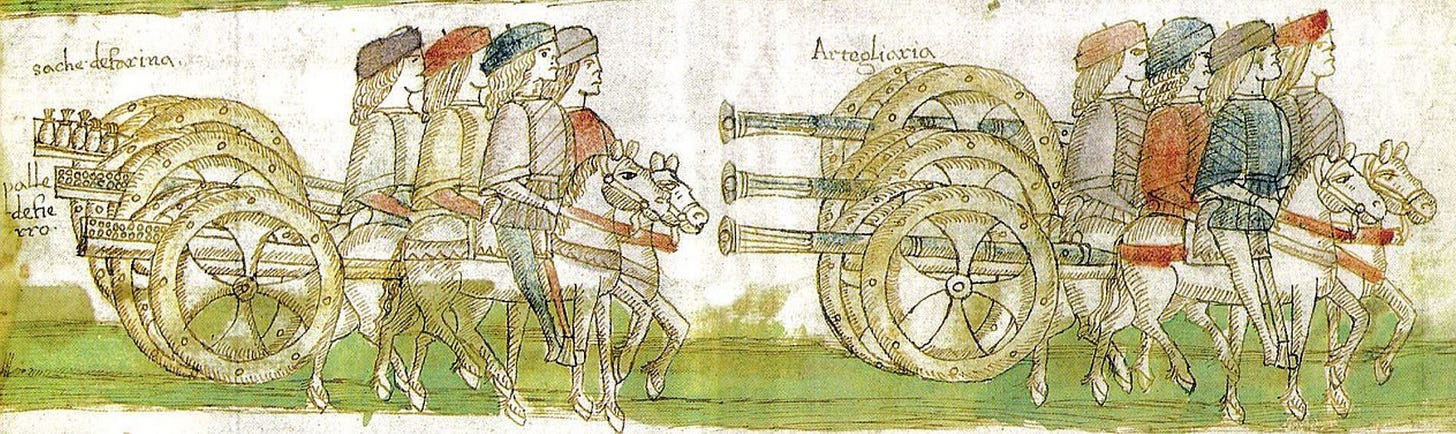

So when Charles VIII of France invaded Italy in 1494 to make good his claim on the Kingdom of Naples, he brought along a massive artillery train. The heaviest guns were sent ahead by ship to avoid the barriers of the Alps and Apennines, then dragged more than 700 km from La Spezia to Naples. These proved their worth in several sieges along the way, where medieval town walls proved no match for the gargantuan cannons.

News of their power preceded the French advance, prompting many towns and fortresses to surrender without a fight—including Naples itself, which capitulated in February 1495. Charles spent several months there arranging his affairs, then left a strong garrison behind when he took the rest of his army back to France. This time, his gunners dragged many of the large-caliber pieces over the Apennines, recruiting local mule teams to assist.

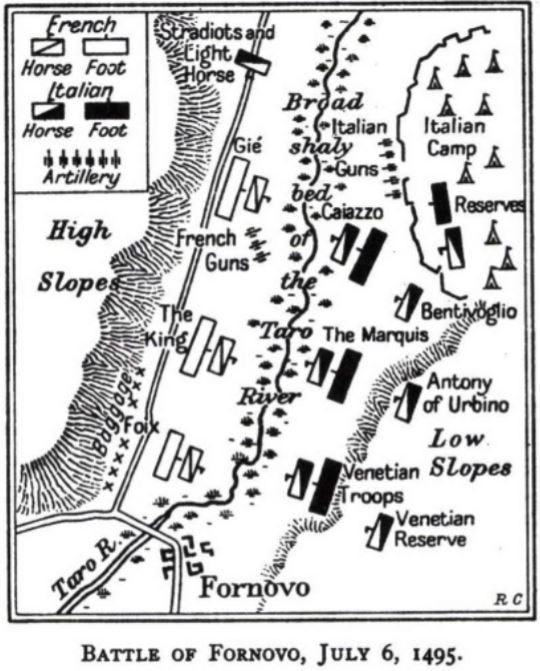

In the meantime a coalition of Italian states, alarmed at the ease with which Charles had marched across the peninsula, was gathering to block his return to France. As he descended the far side of the Apennines, he found their much larger army blocking his path. They had formed up on the opposite bank of a small river near the village of Fornovo, where the narrow valley forced the French to march directly across its front. Charles drew his army up in three bodies, each with a line of cavalry backed by a line of infantry, and placed his artillery in front of the center.

A small Italian battery opened the battle as the French were moving into position. Charles’ guns replied, but the previous night’s rain had gotten the powder damp and slowed their rate of fire. Many of the Italians were nevertheless convinced that the large battery would sweep them from the field, however, and the few initial casualties prompted their cavalry to charge. The horses struggled up the steep and muddy embankment, allowing the French to easily drive them back. Charles’ guns kept up their fire on the retreating Italians as the rest of the army continued safely down the valley, although some light cavalry did manage to loot the baggage train.

The Battle of Fornovo was one of just a handful of pitched battles during the first Italian War, and the only one to see the use of artillery. It was mere accident that the French guns did not get to truly prove themselves in the field—they were ideally positioned to tear apart dense formations at close range. Instead, the battle fit the mold of other late medieval battles: a short exchange followed by a cavalry and infantry fight. Subsequent battles of the Italian Wars would look much different.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.