A Military-Industrial Complex With a State: Sweden in the 17th Century

Mirabeau’s witticism about Prussia in the 18th century could have just as easily been said of Sweden in the 17th. From the first expansionary wars in the 1560s through the death of Charles XII in 1718, her kings were at war for 108 out of 158 years. Despite a small home population, the Swedish army grew in excess of 150,000, while the navy briefly became the fourth-largest in Europe. At the height of its glory, the Swedish Empire seemed more a military with a state than a state with a military.

It was not naturally suited to play so large a role in the political contests of the 17th century. Its population was only somewhat over two million and its farmers struggled to eke out a living in lands so far north. Nor was it a great commercial nation, edged out of the lucrative Baltic trade by other mercantile powers. Yet it was endowed with precisely those resources which were essential for war. Large copper and iron deposits were cast into artillery and cannonballs. Fine-grained oak and pine forests were used to construct ships and produce naval stores. Charcoal and sulfur deposits fed the country’s gunpowder mills. To a far greater extent than Prussia ever managed, Sweden could arm and equip itself.

This enabled her monarchs’ warmaking in other ways. Exports of key materiel generated large revenues for the crown, as cannon foundries across Europe devoured Swedish iron and copper and navies consumed vast quantities of pitch and pine. Weapons sales also played a key role in keeping the war machine running: although they never made up a major part of state revenues, the private profits they generated were reinvested to give the arms industry an economy of scale. Not just private production, but society itself was built around war: taxation, recruitment, and the raising of supplies were organized down to the lowest level to run with the utmost efficiency. At its height in the 17th century, the Swedish Empire was not just an army with a state, but an entire military-industrial complex.

Early Days

Sweden’s rise began in 1523 when she broke free from the Kalmar Union, a centuries-old union of the crowns of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It had grown increasingly contentious in Sweden as the nobility chafed under the domination of Danish interests, and in 1523 they rebelled and elected their own king, Gustaf Vasa. After a brief war, Denmark recognized their independence the following year. Except for a minor border war fought with Russia and the turmoil of the Reformation, during which Sweden converted to Lutheranism, the rest of his 37-year reign was mostly peaceful.

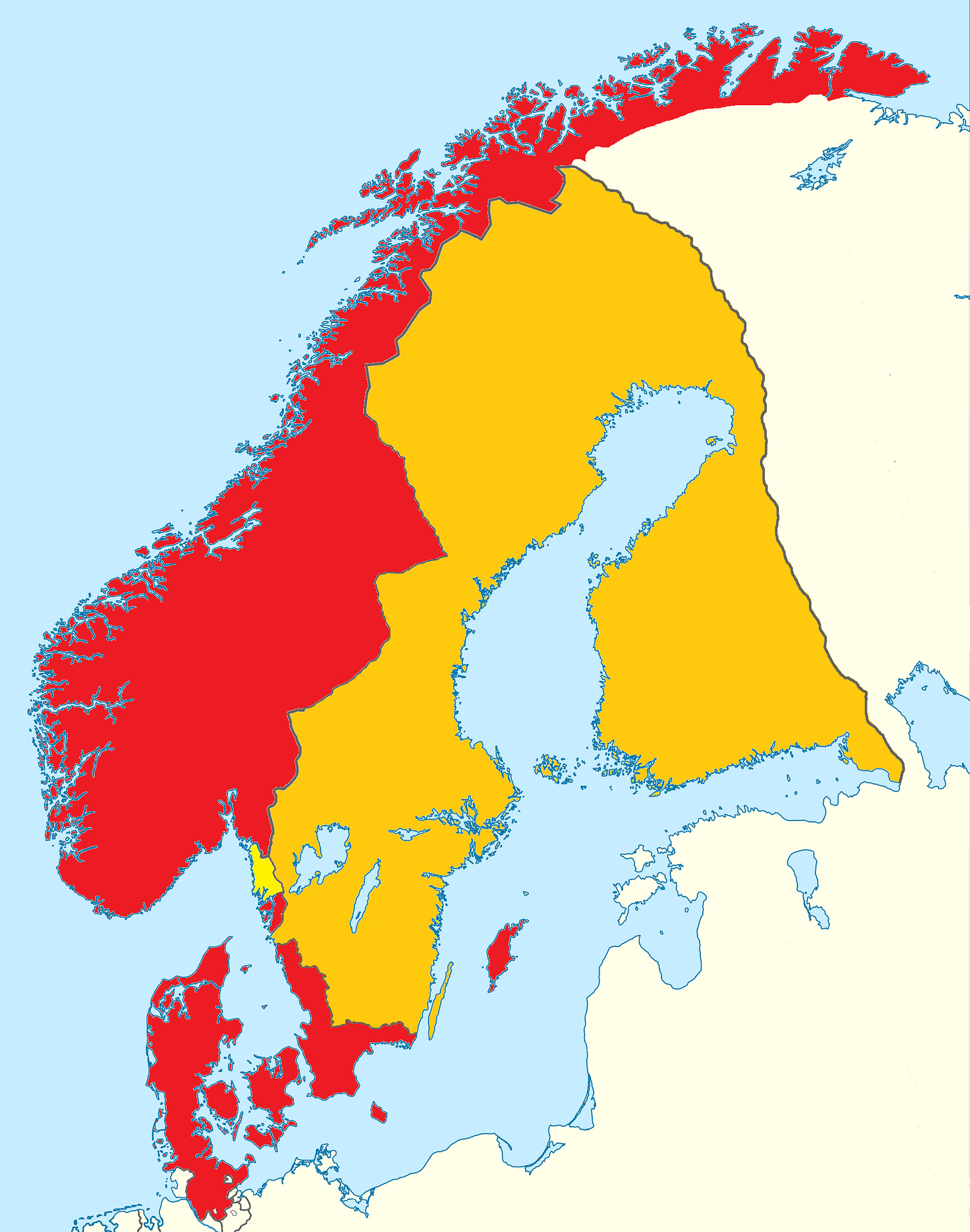

There were good reasons for this restraint. At the time, the Kingdom of Sweden was poor and weak. Although it encompassed most of the modern territory of Sweden and Finland, it was hemmed in on all sides by hostile powers. The Danish crown possessed Norway on Sweden’s western border, and also Scania, at the southern tip of the Swedish peninsula. Beyond the territorial threat this posed, this gave them full control of the Oresund, the main entrance into the Baltic, which they used to collect large customs duties on trade in the region’s timber, grain, fish, and metals. This made up over half the crown’s revenues, allowing the hire of large mercenary armies—a luxury the Swedes did not have. The southern shore of the Baltic was controlled by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, then the largest state in Europe, which controlled several of the richest commercial ports in the region. To the east was Russia, which controlled vast lands and had been expanding westward.

Gustaf’s son and successor Erik XIV was more belligerent. During his eight years on the throne, he got embroiled in major conflicts with all three major neighbors. This started with the Livonian War, Russia’s ongoing effort to absorb the present-day territories of Estonia and Latvia. Erik attempted to exploit the chaos and seize territory for himself in the region; although he gained part of Estonia, this also sparked wars with Denmark and Poland.

Erik was deposed in 1569 because of mental instability, but he had set his country upon a warlike path. His brother and successor, John III, negotiated an end to the war with Poland and Denmark the following year by paying a large indemnity, which allowed him to turn his full attention to Russia. In 1577 he won over Poland-Lithuania as an ally (aided by his marriage to a princess of the royal house) and expanded his hold in Estonia. The war lasted on and off until 1595, leaving Sweden in possession of northern Estonia—this included the Hanseatic town of Reval (modern Tallinn), a significant trade port.

In 1593, John was succeeded by his son Sigismund. The new king had been elected to the Polish crown six years earlier, owing to his descent from the royal house, and shared the Catholic faith of his subjects. This caused discontent among the Protestant Swedes which turned into civil war at the end of the decade. The king’s uncle deposed him in 1599, and there followed a long war between Poland and Sweden, during which the uncle was eventually crowned King Charles IX. Fighting lasted until Charles’ death in 1611, after which a truce was concluded with no change in territory.

The Beginnings of an Arms Industry

The great series of wars that began in the 1560s under Erik XIV required a lot of equipment. The Swedish arms industry was still primitive. Although there was some production of primitive wrought-iron cannons, kings were forced to buy muskets, pikes, cannons, and gunpowder from elsewhere in Europe, and to ramp up mining production to pay for it. In order to make this more economical, he laid the foundation for a domestic arms industry.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.