Book Discussion on The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History

Below is a synopsis and discussion of The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History by Tonio Andrade. The author is a military historian interested in China and its divergence from the West, who first made his mark with a book on the Chinese conquest of Dutch Taiwan.

Synopsis

The Gunpowder Age looks at Europe and China’s parallel military developments from the first uses of gunpowder on the battlefield, sometime in the 9th century or so. In doing so, Andrade engages with the idea that Europe’s later military dominance was incubated by protracted competition between relatively stable states, which encouraged military innovation. He argues that these dynamics also applied to several periods in East Asian history, and uses them to explain several key developments. He also argues that the ascent of the West was not nearly so monotonic as often portrayed, and that the long transition from the Ming to Qing dynasties—which also saw wars with Japan and Korea—was another “warring states” period whose innovations temporarily brought China back to parity with the West.

Part I: Chinese Beginnings

The first part looks at the emergence of gunpowder weapons and their earliest iterations. Chapter 1 applies the competing-states model to the era that gave birth to gunpowder, what Andrade calls the Song Warring States period. During the first two phases, from 960 to 1234, parts of northern China were ruled by dynasties founded by steppe peoples (the Liao, Xi Xia, and Jin). These were relatively sophisticated and stable states that exerted competitive pressure on the Song, inspiring lots of military and administrative innovation. This accelerated in the third phase (1234-79), in which the Mongols slowly overwhelmed the Southern Song.

Chapter 2 looks at the gunpowder weapons that emerged from this process, beginning with the formulas for gunpowder itself. It was a long period of experimentation, as early formulations were not nearly so explosive; as such, many early weapons were used as incendiaries and bombs rather than propellants.

The gun did not emerge until around the time of the Mongol conquest, as described in Chapter 3. The exact moment is harder to identify than one might think, because descriptions of weapons are often vague, but it is clearly attested by the early 13th century. Its subsequent development is detailed in Chapter 4, which notes “a general truth about early Ming guns: they were designed not for bombarding ships or walls but for killing people” (p. 61).

Part II: Europe Gets the Gun

Chapter 5 discusses the adoption of guns in Europe and the early forms they took. The two separate strands of development are brought together in Chapter 6, which discusses the development of large cannons in the West. It proposes a compelling reason for why Europe developed them but China did not, hinted at earlier in the text: medieval European walls were thin and constructed of brittle stone, while Chinese cities were typically girded by rammed-earth walls that were extremely thick (10-20 meters at their base). Europeans therefore had a strong incentive to develop castle-breakers that would be completely ineffectual in China.

Chapter 7 then looks at the emergence in Europe of the classic long-barreled gun, which fired farther and more accurately than Chinese variants. Whereas length-to-bore ratios were about equal around the mid-15th century, European guns quickly surpassed those. Andrade considers several explanations for why this was not developed in China, before suggesting a warring-states explanation: after 1424 and especially 1449, the Ming saw a long century of peace, while Europe was wracked with wars that saw gunpowder transform the continent—the Military Revolution thesis, discussed in Chapter 8. Yet two Sino-Portuguese clashes in the 1520s, detailed in Chapter 9, show that this did not confer an absolute advantage and that Ming forces were still able to adapt in the face of Western firepower.

Part III: An Age of Parity

In this section, Andrade argues against the simple narrative of accelerating European ascendance following their adoption of the gun, and argues that China rapidly adapted to Western innovations introduced by the Spanish, Portuguese, and Dutch. He rebuts two specific claims frequently made about this period: that the Chinese abandoned any innovation, and that European drill gave their infantry a unique advantage.

Chapter 10 addresses the first of these claims, examining Chinese encounters with Western guns, which they called “Frankish cannons”. Far from eschewing these innovations, it was precisely the Confucian scholarly class that advocated their adoption: they suggested mounting Portuguese cannons on the Great Wall, had copies made and distributed, encouraged experimentation, and celebrated their use in poetry.

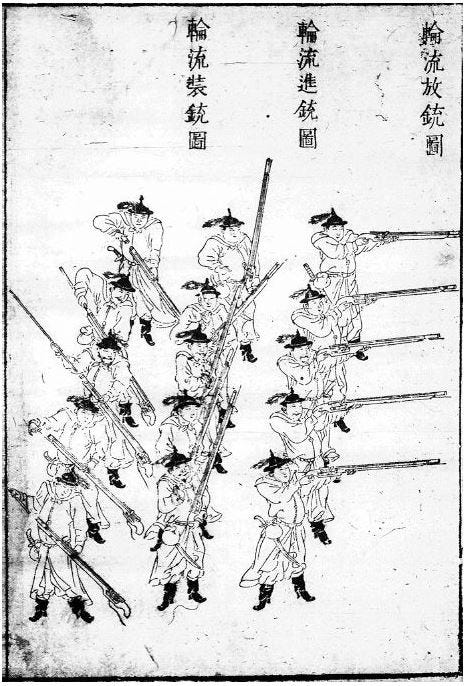

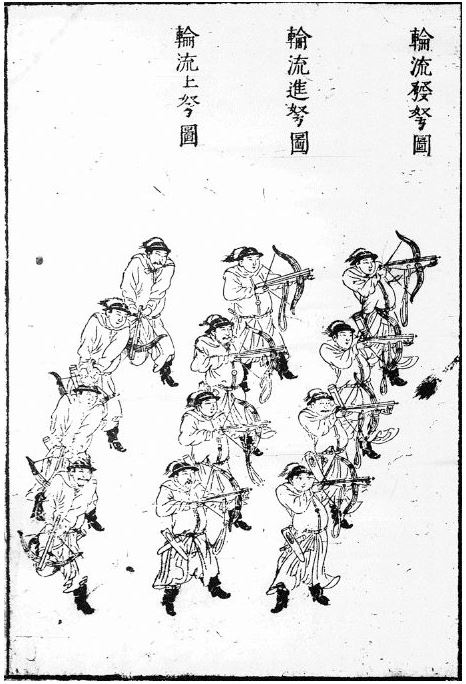

Chapter 11 addresses the second. As early as the Warring States Period, China had developed elaborate drill techniques for crossbowmen which allowed sustained volleys in the face of the enemy. This was apparently never lost, and was detailed in manuals from the 8th, 9th, 11th, and 17th centuries, with many attestations of its use in between.

Chapter 12, which narrates the adoption of the musket in Japan, China, and Korea, shows how the Ming explicitly drew upon this tradition to develop volley fire for firearms—the earliest clear mention of such. The Koreans further refined this, and developed perhaps the best firearm infantry in the world in the early 17th century.

Direct contact between European and Asian trained infantry is described in Chapter 13. There are just a few examples: two each during the Ming war with the Dutch over Taiwan in the 1660s and during the Qing war with the Russians along the Amur River in the 1650s (involving Korean musketeers). Andrade cites Chinese victory in all four to argue that Asia and Europe were at rough parity through the 17th century.

Nevertheless, Andrade highlights two exceptions in which Europeans were clearly superior: naval technology and fortification. Chapter 14 looks at the first of these, showing how much better broadside ships with multiple gundecks and complex rigging performed in combat. The Chinese attempted to adapt, replicating Western naval guns, bringing Portuguese artillerists to Beijing to train their own gunners, and even building an entire fleet of multiple-decked war junks (which the Dutch destroyed these in a sneak attack).

Chapter 15 looks at fortifications. Although the Chinese apparently made some efforts to adopt the bastioned fortress, it never really caught on, nor did Western siege techniques, as shown in four Chinese sieges of European forts: two each during the previously-discussed wars with the Dutch and Russians. The Chinese were ultimately successful in three, but two saw a much smaller force hold out for a long time, and only one succeeded through bombardment. That was the siege of Fort Zeelandia (covered in detail in Andrade’s book Lost Colony), in which the Chinese were eventually shown effective siege techniques by a German defector.

Part IV: The Great Military Divergence

The final section considers the growing divergence between East and West that begins in the mid-18th century. Chapter 16 looks at two explanatory factors. The first was the long period of peace that lasts in China from 1760 until the start of the First Opium War in 1839. Few acquired any military experience, drill became a ritualized display, and, above all else, the military stopped innovating. In a very concrete sense, the Qing were the victims of their own success.

At the same time, Western experimental science was beginning to make a serious impact on military innovations: ballistic measurements that allowed more effective gun designs, sensitive time measurements that allowed precise air-burst fuses, the application of steam power to ships, etc. The result was a crushing British victory in the First Opium War.

Chapter 17 shows that the Chinese were far more responsive to this than is often credited. Even during the war, they started manufacturing modernized carronades, improving their carriages and gunnery, and developed man-powered paddleboats that could navigate shallows. Conscious of just how much their defeat owed to their scientific backwardness, officials developed a farsighted modernization plan after the war, translating Western publications and buying up guns and ships. They even managed to create a small-scale replica of a steam-powered ship, but lacked the precision tooling to make it very efficient.

The reason for this, and for other initial failures more broadly, was a lack of the necessary technical and intellectual infrastructure: advanced mathematics, technical drawing to accurately reproduce designs, and above all “machines for making machines” that could create precision tooling. And the impetus to reform eventually fizzled out from a lack of official interest: although defeat in the First Opium War was humiliating, British aims were limited and did not seriously challenge imperial authority.

This changed after 1850, when a series of large-scale rebellions and foreign wars created what Andrade argues in Chapter 18 amounted to a warring-state dynamic. The Taiping Rebellion (1851-64) created an organized competitor within southern China around the same time as the Second Opium War (1856-60), even as dangerous rebellions raged on the periphery. This compelled the Qing to focus their energies and money on remedying the faults within their military, especially their deficit in “machines for making machines”. They imported machine shops wholesale from America and established the Jiangnan Arsenal and Fuzhou Shipyard to develop modernized weaponry.

Andrade argues that, although many of these efforts are often deemed failures, they lay the groundwork for subsequent progress. The Fuzhou Shipyard was especially impressive: an entire complex that had schools to teach math, science, and technical skills, along with the advanced machinery. The Chinese navy reached a high degree of technical sophistication by the latter decades of the century, but by the time they fought the French in the 1880s and Japanese in the 1890s, the suppression of internal rebellions had removed the stimulus to reform and Fuzhou was no longer fully funded. Even then, failures in both those wars owed more to self-imposed handicaps borne out of fear of future uprisings than straightforward technological backwardness.

Discussion

Just as a survey of the evolution of gunpowder warfare, The Gunpowder Age stands on its own as an incredible story. The overview of the first few centuries of innovation is fascinating and picturesque, and it is surprising how quickly gunpowder weapons became pervasive in Chinese armies: by 1380, Ming policies dictated that 10% of troops should be gunners, and by the later 15th century this number was 30%. Andrade also highlights the mystery of the gun’s transmission across Eurasia: although it diffused quickly throughout Western Europe in the first half of the 14th century, its first clear attestation in the Middle East is not until the 1360s or 70s, in Russia and Central Asia in the later 14th century, and in India not until the 1440s.

The theoretical arguments are equally compelling. It takes one glance at the old walls of Chinese cities to appreciate Andrade’s explanation for the initial divergence of Western gun technology.

So too are the two broader themes that run through the entire book: the “warring states” model for innovation and the rejection of Confucian conservatism as a reason for China falling behind. The constant warfare of the Song period furnishes many examples of official interest in gunpowder, producing a wild proliferation of new weapons, and it was precisely those Confucian officials who, far from being an innately conservative influence, took the greatest interest in them.

The flip side of this is that during peacetime, military science stagnates or regresses. Andrade does not expand on this as much, but occasionally hints at a few things which amplify these dynamics. In the first place, Chinese administration was sufficiently centralized that a lack of imperial interest was often sufficient to kill a project: although provincial officials might experiment with a new technology, it was hard to persuade the authorities to adopt it absent a compelling threat. Related is the burden of administering a state as large as China and keeping many sets of elites happy—a competing priority for resources to the military.

One does sense a lingering culture of conservativism which is more imperial than Confucian. When Portuguese artillerists were brought to Beijing to teach their craft in the 1620s, court officials expressed concern that this would reveal Ming vulnerabilities to the outside world. Similarly, the Qing military’s poor performance against the French and Japanese in the 1880s and 90s owed much to a divided command structure designed to reduce the chance of a coup. After all, military readiness is not always the most pressing security concern.

Parity in the 17th Century

Part III, on the period from the mid-16th to mid-18th centuries, was in some ways the least satisfying. Chapters on Chinese willingness to learn from the West and innovate on their own were fascinating, and Andrade persuasively argues that Asian musketry was up to if not beyond the standards of European armies; but I was not at all convinced that this reflected an age of military parity.

The argument rests on very scanty evidence: just a handful of direct clashes between Europeans and Chinese, never much more than a thousand men a side, and in all but one of which the Europeans were greatly outnumbered (the sole exception involved fewer than a hundred men per side). Nor does Andrade really look beyond the limitations of the evidence. There are several questions that could put things in fuller context:

1.) How readily available were well-trained troops? Part of the strength of European militaries was that, once pike-and-shot tactics proved themselves in the first quarter of the 16th century, the continent was flooded with experienced veterans and officers who could command them. This allowed generals to quickly raise well-trained armies, even in countries such as France or England that had rather poor homegrown infantry.

Could a Chinese general do the same? The chapter on Asian musketry points to the difficulty of estimating the proportion of firearms in 16th-century Ming armies (not just what was advocated in writings), and suggests that northern Chinese troops took to these reforms less readily. It seems that the Koreans and Japanese subsequently employed a very high proportion, but Andrade acknowledges more research is needed for the later Ming and Qing.

2.) How well did Asian musketry perform within a larger tactical system? Technical proficiency alone is insufficient—it must be coordinated with other arms to be effective in battle. This was one area where Western armies excelled: their pikemen were also well drilled, and musketeers were practiced in taking cover behind them when threatened by enemy cavalry.

Although Chinese military manuals describe similar tactics (using spearmen instead of sturdier pike formations), none of their battles against Europeans reveal much in the way of combined arms—we would have to look at intra-Asian battles to see how well their tactics worked in practice. The only mention of such in the book was the failure of Korean combined arms against Manchu cavalry, but there was no examination of the tactical dynamics.

3.) How well did Asian artillery perform in battle, as opposed to sieges? Field artillery was already assuming an important tactical role in Europe by the later 16th century and was very often decisive in the 17th. Little attention is given to Chinese field artillery or how effective it was in battle.

Silence on these questions leads me to suspect that 17th-century Chinese armies were not quite as effective as Andrade suggests. This impression is amplified by his accounts of Chinese siege warfare: despite very good artillery and gunnery, their subsequent failure to adopt Western fortifications or siege techniques suggests deeper institutional problems. This bears comparison to the later 19th century, the First Sino-Japanese War in particular: the Chinese were in many ways technologically superior to the Japanese—the fleet especially—but their efforts were doomed by poor leadership, tactics, and administration.

Nevertheless, this section persuasively argues that the Chinese at least narrowed the gap with the West during this time, in line with the warring states model. At the very least, this will hopefully motivate further research.

Cultural Advantages

Part IV marks the appearance of a completely new factor in the dynamics of military evolution, namely the West’s culture of scientific innovation. This is especially interesting following Andrade’s rejection of glib cultural narratives around Confucian conservatism—he admits to having been initially skeptical about the role of science as a decisive factor.

In light of this, it would be interesting to reexamine earlier periods of European innovation. For example, while the warring states explanation for why Europe invented the classic gun in the 15th century seems adequate, was there any unique culture of tinkering and experimentation that led to continued innovation? These sorts of compounding phenomena inevitably appear earlier than one would expect, and it seems at least possible that Europe had certain cultural advantages predating the emergence of formal science in the 17th century.

Looking at things from the other direction, it seems that advanced bureaucracy and widespread literacy were an underappreciated cultural advantage for the Chinese throughout much of the Gunpowder Age. It is striking how often innovations seem to be made at bureaucratic suggestion, and the adaptation of crossbow volley fire to muskets was apparently directly inspired by older practices formalized in texts. Although there are wispy hints that Europeans also developed sophisticated infantry drills in the Middle Ages—the fighting march certainly required discipline and training, and Richard at the Battle of Jaffa employed a second line of crossbowmen that reloaded while the first was shooting—but there is no indication that this was ever institutionalized.

The Age of Scientific Warfare

Given the extreme disparity between China and the West by the time of the Opium Wars, the subsequent reform efforts are all the more impressive—this book provides a useful corrective to the impression of a China that simply floundered through the rest of the century. European powers benefitted from the compounding effects of technological advancements, and it is all the more incredible how Qing reformers undertook to scramble up the steepening exponential curve. They attempted to build the groundwork for future advances even as they struggled to produce basic weaponry, instituting scientific and mathematical education, technical training, precision machinery, and so forth.

And the results were far greater than is commonly understood. Although China lost all her wars against foreign adversaries in the 19th century, none of these were catastrophic, and by the end she could produce advanced warships, smokeless powder, and was largely self-sufficient in arms and ammunition.

These efforts lend poignance to China’s later tragedies of the 20th century. Despite the subsequent chaos of the early Republic, the country was by no means doomed to backwardness for the next half-century. Arthur Waldron describes in From War to Nationalism: China’s Turning Point, 1924-1925 how by 1924, most outside observers were relatively optimistic about China’s fate. They saw a country that was making great strides in technology, education, and economic development, even as the Beijing government appeared on the verge of effecting a political reunification. Western powers, far from gathering around China like predators around a wounded beast, were trying to usher her into the family of advanced nations via mechanisms in the Washington Naval Conference and other international agreements. The catastrophic Zhili defeat in the 1924 civil war, Waldron notes, triggered an unraveling that might otherwise have been averted.

Taken altogether, the long shadow of these events helps explain the Chinese Communist Party’s twin obsessions with internal stability and techno-scientific transformation. In one critical aspect it has succeeded: China’s industrial base is already the greatest example of “machines for making machines” the world has ever seen. Manufacturing is so vertically integrated that it is hard to imagine any other country displacing it anytime soon.

War is clearly a great motivator for this. Yet it is hard to say what a 21st-century great-power war would look like. The 20th century provides us a ready model for how industrial might determines military power, but globalized markets and dollar dominance make the effects of economic measures on warmaking abilities completely unpredictable.

Moreover, the world’s largest powers, with the exception of Russia, are in one of the longest periods of peace ever seen. The military actions fought by the US, China, Western Europe, and India over the past 50+ years are closer to the complacent border actions of the late Qing than serious contests that induce real reform. Even with recent talk of increasing tensions, it is hard to imagine any of their militaries fighting a full-scale interstate war. Sometimes the past doesn’t so much illuminate the present as make it appear surreal.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. If you are interested in reading The Gunpowder Age, you can purchase it here:

You can find other book discussions here. If you are interested in supporting the Bazaar of War, you can subscribe here:

Paid subscribers receive an electronic copy of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and get exclusive access to monthly longform pieces. You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Have you read Firearms: A Global History by Chase? Seems to tackle many of the same ideas addressed in this book. If you haven’t read, worth your time.

I think I'll give it a go, thank you. The end of the text on chapter 16 seems to be cropped by the way - it ends "The result was a crushing"