Book Discussion on The Cutting-Off Way: Indigenous Warfare in Eastern North America, 1500-1800

Below are notes and a discussion of Wayne E. Lee’s The Cutting-Off Way: Indigenous Warfare in Eastern North America, 1500-1800. I hope to do more of these on books I read that fall outside the usual topics discussed here or which approach them from an interesting angle. My previous one was on Christopher Goscha’s Road to Dien Bien Phu. I hope you enjoy.

Synopsis

This book presents a new model for looking at Indian warfare, looking at how their hit-and-run tactics were shaped by the broader context of social organization, logistics, and strategy. It also looks at how Indian nations interacted with and were influenced by Europeans, examining these changes within the framework of cutting-off warfare.

Chapter 1: Introduction: The Eastern Woodlands

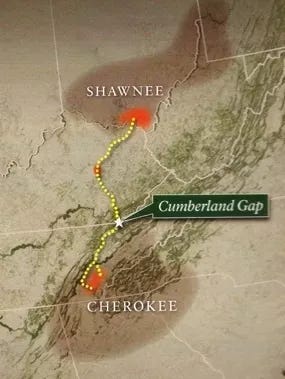

This introduces the “cutting-off way”, a term coined by the author to describe a paradigm of Indian warfare that relies mostly on long-distance raids that used surprise to strike quickly the retreat with loot, scalps, and prisoners. This paradigm describes most warfare in the Eastern Woodlands following the collapse of large centralized societies along the Mississippi, and owes to several factors:

Settlement patterns: clusters of towns surrounded by large hunting areas, which meant attackers had to cross long distances and strike quickly before help arrive from surrounding

Demographics: Low population density meant high percentage of society was involved in war, societies could not endure high casualties.

Social structure: relied on different incentives, men could not be mobilized the same way

There were some similarities to European warfare, but they were fairly superficial:

Pitched battle: mostly a face-saving exercise when a raid failed to achieve surprise, was broken off quickly

Sieges: more like blockades, but could usually not last long for fear of reinforcements

Encounter battles: ambushing a hunting party or another war party, seeking to envelop but not fully surround them, avoiding a bloody fight to the last man

Chapter 2: The Cutting-Off Way of War

Several examples and case studies of the cutting-off way, drawing the focus away from the tactics of the cutting-off way and toward operational methods. Several examples:

Two Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) expeditions a century apart, in which a large party traveled a long distance then dispersed into small bands for individual raids.

A Choctaw raiding party discovered in Chickasaw territory: could no longer attack as a body, so split up to attack in smaller groups

Ability to sustain operations and fight pitched battle was limited, so the emphasis was on hit-and-run attacks. Counterexample of the French besieging Natchez: “Do you remember or have you ever heard it said that Indians have remained in such great numbers for two months before forts?”

Case study of a large-scale attack for which there are sources from both sides, during a period of Mahican-Mohawk hostilities. Several hundred Mahicans traveled 200 miles by rivers to launch an attack on a fortified Mohawk town. Despite achieving complete surprise and inflicting several casualties, the palisade prevented a massacre and the two sides skirmished outside the village for several hours. The Mahicans withdrew before Mohawk reinforcements arrived from neighboring towns, who pursued through the night and ambushed them the following morning as they departed their camp. After a day-long siege of the camp that extracted heavy casualties on both sides, the raiding party escaped the following night.

This case-study contrasted with other examples illustrates certain aspects:

The Mahicans could have attacked assaulted the town, besieged it, or fought a pitched battle outside its walls—but that was only a last resort

The arrival of Mohawk reinforcements from nearby villages forced the Mahicans to retreat: the expectation of this forced quick hit-and-run attacks

There were occasional encounter battles, in which warriors tried to envelope the enemy in a half-moon formation, individuals slipping from tree to tree.

Chapter 3: The Indians Went Hunting

Overview of how Indian war parties kept themselves supplied, showing the mutual influence of logistics and operational methods in the cutting-off paradigm; how these methods gave war parties great flexibility but also limited their endurance.

Case study of one of several French-allied Lenape war parties that attacked Braddock’s expedition in 1755. After capturing a few English prisoners, they returned to their base camp with only a few French-provided biscuits to eat for the 65-mile trek. At the camp, they were given venison by a hunting party that had been left behind; after the other war parties came back, they all returned home.

The first part of every expedition was the approach march: sometimes hundreds of miles by river and land. Five types of food could be eaten en route:

Ground corn that could be eaten on the move

Corn flour that was mixed with boiling water—required a campfire

Dried meat, prepared in advance

Expedient food: wild plants & small game that could be hunted on the move

Larger game hunted more deliberately

Expeditionary routes:

War parties traveled along rivers and portages whenever possible, which made longer-distance routes predictable, using canoes that could hold substantial supplies.

When traveling by land, they followed routes that passed through clusters of towns where they could expect hospitality, or along buffalo migration routes for easy hunting.

Long-distance routes, especially by water, were fairly regular and predictable.

Expeditionary logistics:

Often set off fairly light, with as little as 3-4 days of ground corn, but other times with much larger packs (which any prisoners taken during the expedition would be made to carry).

They would hunt along the way, stop at neutral villages for sustenance, and cache food before gathering at a large base camp from which they would launch attacks.

Logistical limitations (availability of game, reliance on hospitality) meant that war bands converged by separate routes on the base camp.

Returning from an attack, they moved quickly and ate little to evade pursuit, relying mostly on food they had cached.

These logistical constraints meant that war parties could not remain in the field year-round, except occasionally with European help: to feed them and their families back home, who depended on the warriors to hunt during the winter. As such, it was impossible to take and hold ground (for which they in any case lacked the manpower to occupy); rivals were only driven from an area after many years of repeated raids.

Chapter 4: Peace Chiefs and Blood Revenge

This is the most “anthropological” chapter in the book, explaining what war meant in a social context, and explaining how escalation of hostilities was managed and how wars were ended.

Case study of the 1622 Powhatan massacre of English settlers in Virginia. After the resignation and death of a Powhatan leader who enjoyed good relations with the English, his successor sought English help against an Indian rival; their refusal caused him to view them and their expansion with mistrust. The Powhatan attacked outlying settlements one day early in 1622, killing ~350. Several key points:

The Powhatans viewed this as a limited attack and did not press it beyond the outlying settlements—this was probably intended as a warning message

English casualties were further limited by warnings of the attack by Powhatans living among them.

The Powhatans expected limited retaliation in turn, for which they prepared.

The attack was interpreted very differently by the English, who sought the wholesale destruction of the Powhatans.

Case study of the 1715-53 Creek-Cherokee war, begun when an anti-Creek faction of the Cherokees violated customs by killing a Creek emissary. When other Cherokees learned of this, they immediately went into a defensive posture, expecting retaliation. They fortified many frontier towns over the next few years, but Creek raids over several decades forced them to abandon many of these.

Warfare was complicated by the three overlapping functions it served:

Political or economic: access to hunting grounds, teaching lessons to neighbors, etc.

Revenge: death of a kinsmen required a blood debt to be paid, but the aggrieved could accept something less than eye-for-an-eye retaliation in order to limit escalation.

Personal status: taking of scalps and prisoners increased individual warriors’ prestige. This often prolonged or motivated wars.

The extent of a war was determined by internal factors:

In cases of blood revenge, the size of the war party depended on the prestige of the aggrieved party; also depended on opportunities for individual status.

This made it difficult to separate the different motivations for war, sometimes lead to periods of “not-quite-war” characterized by sporadic killings.

Escalation was further limited by extensive ritual demands before any war party set out. Religious leaders could also act as a brake on war chiefs’ power.

Functions of prisoners:

Proof of social status for returning warriors

Object of revenge to help the community grieve: “Ironically, torture may have helped end feuds.”

Adoptee to replace lost population (more usually for women and children; men were more likely to be tortured)

Slaves (though not initially exchangeable chattel to be sold on an open market)

This explains the differences with European warfare:

Harsher in some cases (e.g. the Mystic massacre, in which Connecticut colonists and their Narragansett allies slaughtered an entire Pequot village in revenge for their killing some unarmed men and women, depriving the braves of valuable prisoners)

More merciful in others: Indians accused Europeans of conducting “sham fights” for doing prisoner exchanges or allowing the garrisons of surrendering fortresses to march out—explaining why France’s Indian allies attacked the retreating garrison of Fort William Henry [this reputation persisted: during the siege of Detroit in the War of 1812, the British commander got the fort to surrender by warning that he could not control his Indian allies.]

The role of resident aliens from one tribe living in another tribe’s village: served a function between hostages and marriage alliances.

Built up mutual affection, often functioned as an intermediary during the build-up to hostilities

Could warn locals of an impending attack by the resident’s tribe, limiting the need for retaliation (as with the Powhatan massacre of 1622).

Chapter 5: Fortify, Flight, or Flee

Looks at Indian defensive strategy, and how fortification styles evolved in response to European technology. During times of war, Indians built palisades around vulnerable towns. Over time, some added bastions to allow crossfire. This may have been introduced either by Europeans with gunpowder, or was a residue of the large centralized Mississippi societies, whose settlements had square bastions built into the walls. Lee uses the examples of the Tuscarora and Cherokee in the 18th-century Carolinas as two contrasting approaches to European.

Tuscarora in eastern North Carolina: rapidly adopted European-style forts during their war with British settlers in early 18th c. They successfully repelled two English expeditions this way, prompting them to invest more in fortifications, but this proved a dead-end: the English mounted a third expedition in 1713 that used advanced siege techniques to take their main stronghold, resulting in the slaughter of the garrison and defeat in the war.

The Cherokees, by contrast, abandoned their villages during a war with the British later in the century. Instead, they ambushed British columns using the half-moon attack, concentrating on the baggage train in the rear: unlike Indian war parties, European troops were logistically constrained and had to withdraw. Although the Cherokees suffered from these incursions, they were able to negotiate a reasonable treaty to end the war. They did continue to erect palisades during hostilities with other Indians, however.

Chapter 6: The Military Revolution of Native North America

A closer examination of how European technology/social pressures changed Indian warfare. He begins with the framework of Geoffrey Parker’s Military Revolution thesis.

Firearms were in high demand among Indians when first introduced, and tribes that got them usually overwhelmed their neighbors. But questions of accuracy, maintenance, and increased logistical requirements raised questions about their utility vs. bows:

Muskets lacked a key advantage they held in Europe: ability to quickly recruit and train vast numbers of soldiers—Indian manpower reserves were just too small. Other factors:

Couldn’t fire as quietly, quickly, or as long as bows

Musketball wounds were more disabling, making it easier to take prisoners

Otherwise fit in with the cutting-off way: initial salvoes of fire, followed by close-in fight

Made open battle much more lethal, hence rarer; marked a shift in preference towards ambushes

European supply requirements (incl. gunpowder) affected how Indians fought them:

They attacked the baggage train at the rear of columns, and supply convoys headed to forts in the wilderness—Americans adapted by building fortified camps along the route [Indians in the Northwest were more successful during the War of 1812, managing to cut off Detroit]

Avoided defending fixed positions against European artillery (as in ch. 5)

The role of fortifications

Archaeology suggests proliferation of forts (stockades) beginning around 1100 AD; arrival of Europeans spurred a new burst of fortress-building

Many complex forts in the Great Lakes area, but these grew sturdier with European contact and developed straight walls to allow crossfire from projecting towers

Once Europeans began employing more artillery and advanced siege techniques in the 18th century, Indian forts became less common; palisades remained common to defend against other tribes

“Native Americans’ technological and social infrastructure proved incapable of taking advantage of all of the components of the European military revolution.”

European influence on political structures and society:

Adoption of gunpowder weapons created dependence on European allies, who preferred to deal with war chiefs over peace chiefs, giving them gifts and prestige—exerted a centralizing effect

Villages often clustered around European forts for protection and access to supplies (and village clusters often asked for forts to be built nearby as a condition of an alliance), but with gradual abandonment of their own forts, Indian villages became less centralized

European demand incentivized the capture of prisoners for sale into slavery. This included a feedback loop with the provision of weapons (and corresponding prestige)—early contact could be a great advantage

Increased prisoner-taking in combat with Europeans, because they paid such high ransoms

Ultimately more a consequence of economic and demographic patterns than specific technology

Chapter 7: Subjects, Clients, Allies, or Mercenaries?

Considers the various types of relations formed between English settlers and the nations they came in contact with from an imperial perspective, using the Irish as a comparison. Identifies five parallels:

Coopting local leaders through grant of titles in order to deal with a single centralized leader

Particular military skills deemed suitable to the landscape

Personal relationships were more effective at mobilizing allies than formal arrangements

Divide & conquer

Power initially wielded through local, nonnative agents who were in competition with one another (although later on these similarities diverged)

Ireland:

English king initially ruled through a deputy who formed military alliances with local chieftains. These troops were useful for irregular warfare in wooded or swampy terrain.

Attempts to ensure loyalty of Irish subjects varied between incorporation into English political structures and forced acculturation, with some advocates for expulsion/expropriation.

Expulsions and settled of English plantations provoked new rebellions, but the English could always rely on some local elites to provide manpower and were more resilient because of home support—allowing them to endure those rare largescale uprisings.

Irish manpower was not as useful outside Ireland, and England was reluctant to employ them elsewhere for political reasons except in extreme cases. Catholics & Irish were weeded out of the army after the conquest.

North America:

“Indian cooperation was the prime requisite for European penetration and colonization of the North American continent.”

Difference with settlement in Ireland is that English in N. America were more concerned about imperial competition with Spain; once they failed to get local Indians to act as imperial subjects as was the case in Spanish America, they adopted more of a garrison-colony Irish model.

Three broad periods:

Indian chiefs offered their warriors as irregular fighters—both bargaining chip and threat. Enlisting their aid was a true negotiation: involved trade treaties, access to firearms, prestige titles, etc. Their help was necessary in wars with other Indians or as clients acting in English interests (fighting hostile tribes, slave trade)

Relations shifted as colonial land hunger surpassed the desire for trade. Indian allies took on more “mercenary” character to drive rivals off their land, and there was increased competition among the different colonies.

Later period of British-French imperial competition saw more Indians forming confederations even as London exerted more control over the colonies—led to view of Indian allies as subject states, mediated through a centralized Indian ruler. But British depended on them for wars against the French, so their authority was still negotiated.

Rapid demobilization of Indian allies combined with colonist expansion after British victory over the French in North America led to a generalized uprising, similar to the Nine Years’ War at the end of the English conquest of Ireland (1593-1603). Reflected discordant views of the relationship: subject/ruler vs. client/patron. This backfired during the American Revolution, when using Indians against the colonists was politically costly.

Differences between the two:

North America was much larger, so even after colonial expansion created large self-sufficient coastal enclaves, the English continued to rely on Indians on the frontier. They also maintained greater autonomy throughout.

By 1600, the English were recruiting Irishmen as individuals into the army; despite continued political mistrust, they came to be viewed as subjects. Indians were never assimilated.

Chapter 8: War’s Ends

This chapter discusses strategy: the aims that Indians pursued through war and the actual outcomes they effected. This was shaped by the methods of war outlined in chapters 2 & 3 and the purposes of war listed in chapter 4.

Several overlapping motivations for war:

Defense or expansion of territory

Seizure of captives for adoption or sale

Negotiation of tributary relationships

Revenge for insults

Protection of kin

Plunder

Individual desire for revenge that broadens into wider war

Desire to resist enslavement

Long-standing blood feuds

Access to trade goods

Captives for internal labor (vs. adoption, sale, or ransom)

Reputation management

Discussion of the relationship between motivations for war and the expected and possible outcomes. The latter ranged from:

Territorial displacement in extreme cases

Imposing tribute

Maintaining reputation

Gaining captives

Maintaining sovereignty

These outcomes were mostly limited by the means available: logistics and societal structure constrained their ability to conquer and hold territory, although more hierarchical societies emerged around the Mississippi and Chesapeake, where goods could be more easily transported by water.

Territory consisted of three concentric rings:

Town clusters and their surrounding fields

Nearby resources (oyster banks, close hunting, timber), plus area for towns to relocate every few decades (owing to rotting houses, exhausted fields, etc.)

Distant hunting grounds for winter expeditions, which expanded with European demand for deerskins.

This created vast empty spaces between settlements which were considered the territory of one group or another—overlapping claims was a frequent cause of war. Buffer zones sometimes formed around overlapping claims to avoid conflict; boundaries might be marked in a peace agreement.

Discussion of submission and tribute:

“‘Submission’…refers to the admission by one Nation that another’s attacks had made their lives unsustainable, but that rather than move away, or continue to fight at a significant disadvantage, they offered to make peace, usually at the price of some form of tribute.”

Tribute could be symbolic, regular payment of goods, promises of military support, subordination of foreign policy, etc.; payments might be redistributed to other tributaries, and complex webs of relationships emerged.

Example of the Powhatans, who formed an unusually centralized confederacy. The paramount chief expanded via several different means:

Captured the inhabitants of one village cluster, resettled them among his own people

Received another people as tributaries after they fell out with their English allies

Exterminated a third group that he deemed a threat

A more usual course than extermination was forced displacement: making a people’s existence untenable through repeated raids, forcing them to give up their hunting grounds and move elsewhere—the Creek-Cherokee War saw the latter abandon their more exposed towns and ended with a formal cession of land. Sometimes displacement meant moving long distances; other times, within a people’s existing boundaries.

Discussion

The book gives a fascinating explanation for why Indian warfare took the specific form that it did. Coming from a Western or Eurasian perspective, so much of it is counterintuitive: low population densities, large distances between rivals, and a very high percentage of military mobilization created very different constraints and incentives. In explaining this, Lee fills out a lot of the background details that are not necessarily obvious: the “warriors’ paths” that war parties took over long distances, their means of sustaining themselves on the march, and societal factors that influenced everything from strategy to tactics.

This makes for interesting comparative studies too. Because Indian society was less centralized or subject to the control of its leaders, political and personal aims were intertwined through many more aspects of the war. This stands in contrast to advanced Western states, where I argue only grand strategy is the natural domain of domestic politics—execution of those policy objectives is mostly in the hands of government officials, while operations and tactics are mostly left to the military.

My only real complaint about the book is that could have put a bit more meat on the bones. For all the examples and case studies, I came away without a sense of concreteness: there was no overview of the Eastern Woodlands’ strategic geography, maps of the major tribes or timeline of their wars, discussion of the carrying capacity of different regions, the typical duration and extent of most wars, etc. I do recognize that it was mainly written for a more specialized audience and managed to condense an expansive argument into just 200 pages, but that makes the absence of a bibliography even more frustrating.

Overall, The Cutting-Off Way is an excellent overview that presents out a compelling and persuasive argument. If not the easiest introduction to the subject, it has certainly encouraged me to read more on the subject and revisit the book at some point in the future.

If you would like to read more, you can purchase The Cutting-Off Way here:

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Thoroughly enjoyed the Road to Dien Bien Phu and so eager to pickup this recommendation

Thanks for sharing this, it fits in well with a number of my recent reads reexamining the history of the indigenous peoples of North America that do without some pretty worn out stereotyping. I’ll be looking for a copy of this.