Drones, Trenches, and C2: A Recipe for Centralization?

A few weeks back I posted a thread on drones in the Ukraine War, looking at how they were enabling a fine level of command-and-control at the squad level. A video clip showed Russian soldiers being guided in their attack on a Ukrainian position, during which the drone operators warned them of enemy firing positions and approaching vehicles, while directing them to available cover and entry points.

The clip only showed part of the engagement, after the Ukrainian defenders had sustained casualties. The direction given by the Russian drone operators was amateurish and the troops appeared poorly trained. Nevertheless, their attack was markedly effective. The drone operators’ broader situational awareness allowed them to make better and faster tactical decisions than any leader on the ground could, and this more than made up for any other deficiencies.

This points to an important development. So far, discussion of drones has emphasized either their lethality against unprotected ground forces (e.g. in Nagorno-Karabakh or Ethiopia), or how they enable precision fires in a more contested environment (as we currently see in Ukraine). Far less visible has been how they have enabled command and control.

The potential is revolutionary. It is easy to imagine units being similarly controlled at every echelon: UAV-guided squads falling under similarly equipped platoons and companies, with all their imagery feeding into a battalion- or even brigade-level COP. Inevitably, this leads to more centralized control. Although nothing in principle prevents subordinate units from maintaining their independent initiative, the integration of all battlefield information into a single picture gives commanders every motivation to hold a much tighter rein: having just as much information as subordinates removes a significant justification for independent action. This is especially so considering the nature of the fighting.

Echoes of the Past, Hints of the Future

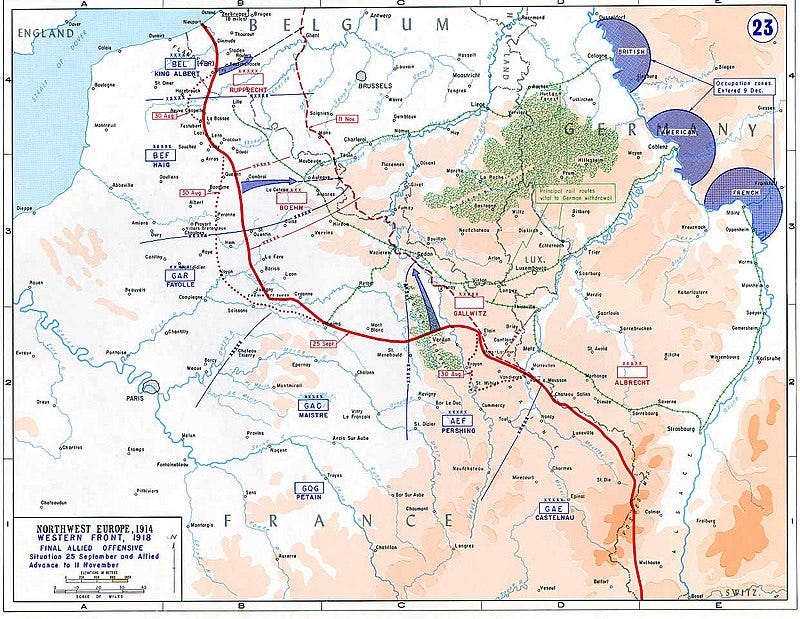

As has been repeated to the point of cliché, the trenchline assaults in the Donbas resemble nothing so much as the Western Front in World War I. This comparison is particularly apt when we consider the command-and-control revolution that took place during that war. After sending countless waves of infantry into the meatgrinder to no avail, generals learned to plan their attacks in much greater detail, coordinating artillery barrages with infantry and tank assaults down to a small-unit level—called stormtrooper tactics by the Germans, methodical battle by the Entente.

They also came to the belated understanding that they could progress much faster by advancing slower, taking one trench at a time in deliberate succession, instead of trying to crack through an entire defensive line in one go. Such tactics proved their worth in the campaigns of 1918. The German spring offensive made several deep inroads into British and French lines, after which the Allies’ riposte during the Hundred Days drove the exhausted Germans back along the entire front.

Similar tactics have already been revived in Ukraine. A Russian document captured at the end of 2022 lays out recommendations for force restructuring in light of recent experience. It envisions the creation of dedicated assault units, mechanized or airborne battalions with attached tanks, artillery, and direct-fire weapons. These represent a significant departure from the Battalion Tactical Groups that Russia entered the war with (which were a late Soviet concept—the new units are closer to the combined-arms assault battalions the Red Army employed late in World War II to initiate major offensives).

The recommendations reflect age-old tactics adapted to the modern battlefield. Assaults are conducted at the company level, with attached artillery and armor supporting infantry platoons. Thorough reconnaissance is carried out beforehand, by patrol and quadcopter. Guns are kept in bunkers and are only brought forward for fire missions, remaining in position no longer than 15 minutes to avoid counterbattery fire. Fires of all types are layered, timed to lift just before the infantry launches its assault upon a limited objective; reinforcements are thereupon pushed forward as the assault platoons prepare their positions to receive a counterattack. Such assaults have been observed by Russian regulars and Wagner over the past several months, with mixed results—likely owing to insufficient training and experience.

Especially interesting amidst all this is the question of command-and-control. Even though WWI infiltration tactics entailed a great deal of synchronization in advance, they left much on-the-ground decision-making to the forward detachments—commanders in the rear simply lacked the situational awareness or means of communications to control events. The Russian document advises somewhat closer control from hardened command posts, with all movements tracked on a map; intriguingly, it recommends against exposing quadcopters during the conduct of the assault.

This conservatism probably owes to Russia’s chronic shortage of small drones throughout the conflict. If they acquire more, we are likely to see more low-level control of the type in the video clip. These techniques will inevitably get integrated into assault unit doctrine, giving higher commanders tighter rein over their subordinates—the groundwork for a highly centralized C2 architecture is already in place.

The Mechanics of Battle

The sum of these developments favors of an incrementalist approach to tactics and operations. Although much has been written on the inadequacy of the division of warfare between maneuver and attrition, their colloquial definitions capture an essential difference. Maneuver seeks to create a breakthrough, which can then be exploited to collapse the enemy’s position; as opposed to attrition, which works by steadily pushing the enemy back from one position to another.

The former is usually to be preferred, as it offers the chance to achieve decisive results with better economy of force. But that is not to say that the latter can’t do better than a merely favorable attrition ratio. Although the slow tempo of methodical attacks gives the defender time to prepare fallback positions and to conduct deliberate withdrawals, this is not something that can be carried on indefinitely. So long as steady pressure is maintained, the defender will eventually have to abandon logistics hubs and other key nodes, precipitating a much more substantial withdrawal. This is not the same as a breakthrough—there is little chance for the attacker to get ahead of the withdrawing enemy—but the pursuit can inflict higher-than-usual casualties and substantial equipment losses.

This is what we saw around Kherson, where the Ukrainians pushed Russian forces off the right bank of the Dnieper. Their assaults were slow and methodical, incurring heavy casualties, until AFU missile strikes on the river crossings rendered Kherson itself untenable. As the Russians fell back to the opposite bank, the Ukrainians hit the withdrawing troops with long-range fires. This was admittedly something of a special case, as the narrow bottleneck formed by the river crossings made possession of the right bank an all-or-nothing affair, and once the Russians completed their withdrawal, the offensive came to a halt along the river.

Kherson therefore serves as a useful illustration of principle, but says nothing about how modern armies will fare in more ordinary circumstances. Everything that improved C2 brings to the offense also benefits the defense. A sector commander can readily judge the shape of an attack and allocate fires accordingly, using precision fires to effectively target enemy troops as they move out into the open. This follows from a basic rule of warfare: advances in firepower favor the defense, while protected mobility favors the offense.

Overall, UAVs enable the former a lot more than the latter. A drone operator might be able to guide his comrades from cover to cover in a small-scale infantry fight, but he cannot do the same for a large combined-arms assault in the face of guided artillery. Indeed, even with the low troop densities of the Ukraine War, the only operationally significant breakthrough following the initial invasion has been the Kharkov counteroffensive, which only succeeded when Russian troop strength was at an absolute low (this is of course pending Ukraine’s expected spring offensive).

Planning the Next War

It is doubtful how much any future war will resemble Ukraine. There are no obvious brewing conflicts that combine wide stretches of open terrain with large and sufficiently advanced opposing forces. The most obvious flashpoints, such as Taiwan or the Himalayas, are shaped far more by sea and air power. Yet the demands of hypothetical conflicts still shape how militaries plan and train, so it is useful to follow these observations to their logical conclusion.

There are two obvious lessons from the current conflict. The first is the premium on execution. Any task so complex demands careful preparation and training, which can be the difference between moderate and staggering casualties. This will demand constant large-unit drills, refinement of protocols, and investment in technology. The specialized assault troops are prone to especially heavy casualties, meaning large numbers of them have to be maintained at a high baseline of proficiency.

The second lesson is the importance of endurance. No matter how well executed, individual assaults incur significant casualties for the attacker. In order to be worth the effort—that is, to accomplish anything more than a slightly favorable attrition ratio—assaults need to be sustained one after another until they cause something to break. This means not just amassing sufficient resources in preparation, but keeping the correct pace: setting a series of obtainable objectives that can be accomplished fast enough to keep the enemy off balance.

This is a tall order. It is very hard to gauge how long a well-defended area will take to fall—witness the Russian experience at Bakhmut—and maintaining sufficient tempo may simply come down to launching series of limited-objective attacks in varying directions. This hinges upon a certain flexibility, all the more so since drone-enabled surveillance makes surprise much harder to achieve. At the very least, attackers must secure their lateral lines of communication to allow rapid shifts in the main effort, effectively increasing their protected mobility in the near-operational zone.

Even under favorable conditions, successful offensives are likely to take a long time—several months, if not the better part of a year. The definition of success itself must also be qualified: limited gains with a better-than-usual casualty ratio might be the best that can be hope for in a single campaign. And it must always be remembered that 1918 Germany did not agree to an armistice because of any particular battlefield defeat, but because the cumulative toll of the war effort had exhausted her resources.

The Future That Might Be

It is somewhat unsettling to imagine that rather low-level tactical and technical considerations could shape the dynamics of wars so profoundly. This is especially so for those raised on fast-paced maneuver warfare—the idea that centrally-controlled trench warfare could be better upsets every notion of good doctrine.

That is not to say that existing trends are inevitable. Different geography, equipment, or political circumstances—to say nothing of new technologies—could easily turn these assumptions on their head. But whether or not they bear out, they will certainly shape military thinking in the medium term. That alone makes them worth paying attention to.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

That's a hugely comprehensive article, thank you.

I can see the centralization, but also see decentralization. Small combined arms units with drone capability can act on initiative instead is waiting for HQ to view the field. using drone ops they can also call for fires from any regional supporting battery in the area.