Red Sea Pirates! Commerce Raiding During the Crusades

Since attention is back on Houthi attacks on shipping through the Bab al-Mendeb, I thought that it would be worth looking at an earlier episode of attacks on Red Sea commerce that took authorities by surprise. This was one of the more colorful incidents of the Crusades, undertaken by the semi-rogue baron Reynald of Châtillon against Saladin, the sultan of Egypt and Syria. Over the winter of 1182-83, he terrorized merchants and pilgrims around the Red Sea in an audacious campaign of brigandage, forcing a panicked response from authorities in Cairo.

The Red Sea was never a major theater in the centuries-long conflict between Christians and Muslims—other than Reynald’s campaign, it hardly figured at all. Then as now, however, it was crucial for Egypt’s geopolitical position, serving as a conduit for the country’s trade. As such, it was one of the foundational elements in Saladin’s grand strategy, which used Egyptian gold to fund his campaigns against the Crusaders and rival Muslim princes.

Saladin in Egypt

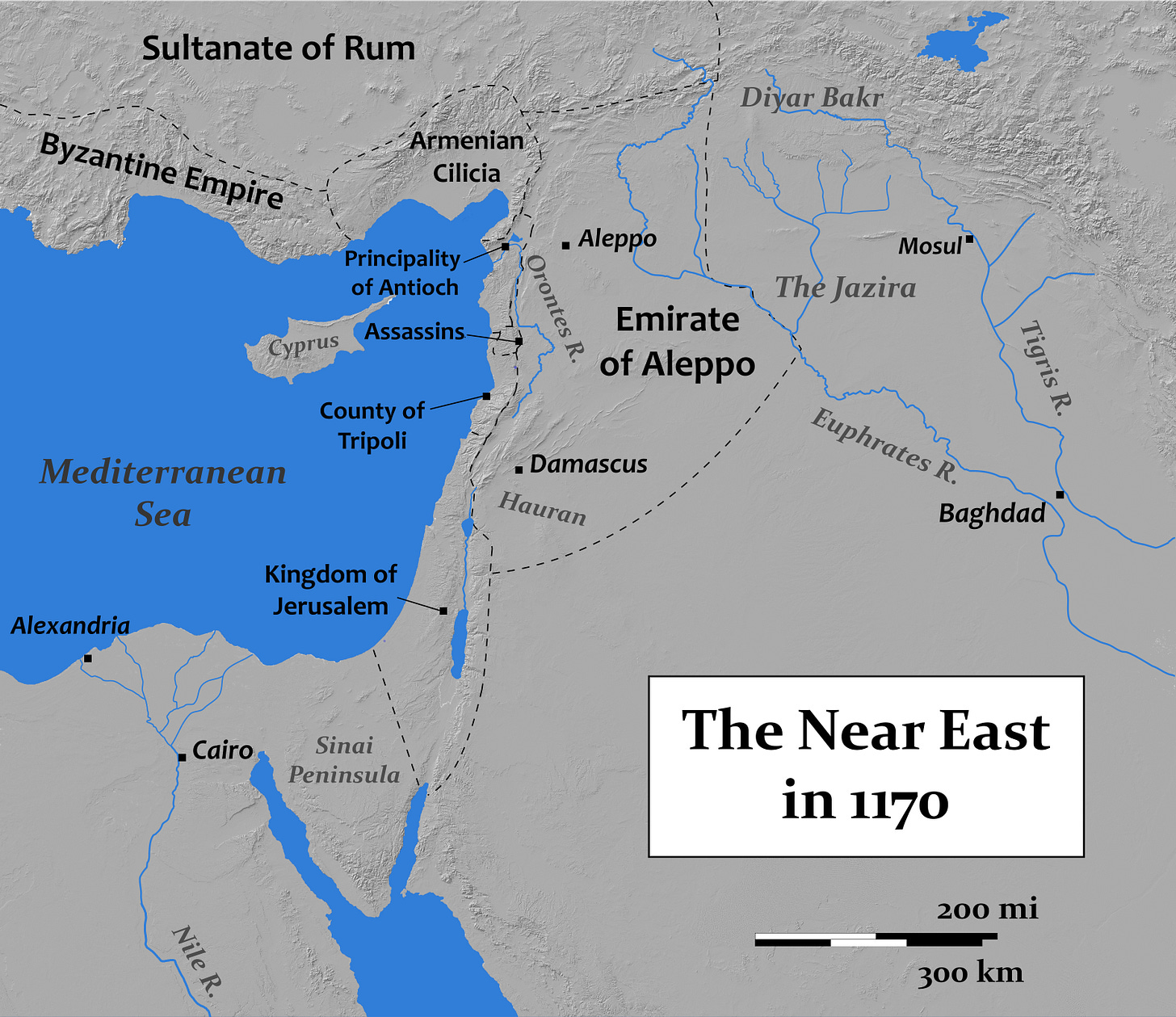

Saladin came to power in Egypt almost by accident. The political map of the Near East in the mid-12th century was dominated by a three-way competition. The Crusader states held the eastern shore of the Mediterranean, while the interior of Syria was controlled by the powerful emir Nur ad-Din. Across the Sinai, the Fatimid caliphate ruled a decrepit empire that had once encompassed most of North Africa, but had since retracted to roughly the borders of modern Egypt.

The Fatimids were Shiites, putting them at odds with the Islamic world’s Sunni majority, who looked to the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad for spiritual guidance. This, along with their political weakness, made them an inviting target for Nur ad-Din. In the 1160s, he made several attempts to conquer Egypt. He appointed one of his best generals to lead these expeditions, a Kurd named Shirkuh, who brought along his nephew Saladin. The first two campaigns were failures—the Fatimids called in help from the Crusaders of the neighboring Kingdom of Jerusalem, who were loath to see Syria and Egypt united—but the third succeeded, and Shirkuh became the Syrian viceroy in Egypt. He died suddenly just two months later, however, and Saladin won the support of the army to succeed his uncle.

Although Saladin held this position until Nur ad-Din’s death in 1174, the relationship between lord and vassal was marred by distrust. Saladin had gained his position through political maneuvers, not Nur ad-Din’s direct appointment, and the Syrian emir feared that he would try to assert his independence. The viceroy, for his part, was torn between several competing obligations: to send tribute back to Syria, to provide for Egypt’s defense, and to maintain his own position amidst a hostile population that still contained many Fatimid loyalists. The last two were especially vexing, as any legitimate efforts to improve his position were indistinguishable from attempts to establish an independent power base. Money problems only amplified this: Egypt was very wealthy, and was supposed to be a cash-cow to fund Nur ad-Din’s wars in Syria, but security expenses reduced the flow of gold to a trickle.

Egypt and the Red Sea

As a matter of practical necessity and as a show of good faith, one of Saladin’s first priorities was to secure his communications with Syria. The Crusaders controlled the entire coastal plain of the Mediterranean’s eastern shore, which meant that Damascus could only be reached via an inland route: across the Sinai Peninsula, then along the eastern edge of the Dead Sea and River Jordan. This route was entirely desert, requiring travelers to pass from one well or oasis to another, which made them extremely vulnerable to concerted attacks. The Crusaders moreover maintained friendly relations with the Bedouin of these deserts, who harassed passing caravans, and held a chain of fortresses from the southern end of the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Aqaba. Merchants and officials were accordingly forced to travel with a large armed escort, limiting the frequency at which convoys could depart.

Saladin began by attempting to reduce the enemy presence in the desert itself. In 1170, he attacked Ailah, the southernmost of these fortresses. This castle was on an island in the Gulf of Aqaba, just off the mainland and some 15 km from Aqaba itself. He outfitted an expedition accompanied by a long camel train carrying disassembled boats; these were reassembled at Suez and sailed around the peninsula to Ailah while the rest of the army marched overland. After a siege of several weeks, the fortress surrendered at the end of the year.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.