Swarms, Packs, and Stigmergy: Animal Analogs for Drone Behavior

“Drone swarm” is a phrase that has become firmly lodged in popular discourse, used indiscriminately to refer to the high number of drones on the modern battlefield. This is a shame, because the original concept, borrowed from the study of insects, is far more interesting. A true swarm exhibits complex behavior that emerges from a mass of individuals following a few simple rules: mostly to calibrate relative motion between individuals, but also to cue an attack.

A swarm of honeybees, for instance, is guided to a food source by scouts that know its location; the rest of the bees follow by maintaining certain spacing with their neighbors (not too close, not too far) and largely matching their velocity. This combines directed intelligence with decentralized control, allowing the swarm to maneuver around obstacles while maintaining its coherence and objective.

When defending the hive, bees follow different rules. Certain kinetic, visual, and chemical signals may prompt an individual bee to sting a nearby object. This releases a pheromone that triggers other bees to do the same in an escalating cycle. Once past a certain threshold of pheromone concentration, the remainder become less likely to sting in order to prevent too many from sacrificing themselves—absent any further cues, the target is assumed to be neutralized.

It is easy to imagine how UAVs could behave similarly: a handful of piloted scouts that seek out targets, followed by a mass of undirected drones that autonomously maintain spacing with their neighbors and respond to attack signals. As things stand now, however, plenty of factors militate against this behavior. The type of cheap and disposable drones that would be ideal for true swarms have short range, making it inefficient to use them to hunt out potential targets. Clustering them too tightly together would make them vulnerable to fragmentation weapons, while keeping them dispersed to the point that they had to coordinate via radio signal would make them vulnerable to jamming.

These are all technical problems, and it is entirely possible that they will be worked out. In the meantime, guided FPV drones work effectively enough at the individual unit level—where they serve other functions besides—that there is little incentive to create buzzing clouds of machines that roam the landscape like Africanized honeybees.

Stigmergic Targeting

The closest we see to swarms at present are the many drones that individually hit a single target—“swarming” about as much as artillery shells do when firing for effect. Even then, it is rare for drones to attack all at once: their attacks are sequential, spread out over minutes or hours. This slow, sequential pattern does loosely resemble another insect phenomenon: stigmergy.

This refers to the use of pheromones to coordinate action over greater distances, like ants laying down a chemical trail for others to follow, which grows into a heavily-trafficked two-way thoroughfare between the nest and a food source. Honeybees use stigmergy even more efficiently: because they move in three dimensions, they can follow pheromones directly to the source, instead of being stuck to the path the first one took.

FPV drones attacking high-value targets, such as armored vehicles, exhibit a sort of stigmergy. They all fly individually to the destination, whereupon they emit signals of their own: BDA for previous attacks and location updates for those that follow. These provide both attack cues and a cutoff threshold once the target has been destroyed. Although this intelligence is far more sophisticated than the type of chemical signals emitted by insects, it allows individual drone teams to make their own attack/wave-off decisions.

Drone Packs

There are nevertheless several examples of multiple drones acting in concert. These are usually more sophisticated, involving more advanced drones and complex attacks. Some of the clearest cut occurred over the skies of Nagorno-Karabakh in 2020, when decoy drones triggered a response from radars or SAMs, which were then targeted by loitering drones.

This evolved from Israeli tactics explored in the 1980s, when decoy drones opened the way for manned aviation to attack Syrian ground sites; itself an outgrowth of the manned decoys used by the Wild Weasels over Vietnam. Work is now being done to make these tactics platform-neutral, executable by a flight of same-type drones: whichever one first encounters an enemy system first would engage it with a frontal fixing attack, while the others sweep around to attack from other directions.

In all such cases, tactics resemble less a swarm than a pack—like hyenas barking at a lion while their companions snap at his flanks. Pack animals’ behavior is far more sophisticated than insects, involving greater awareness of what one’s neighbors are doing. Wolves and whales herd their prey toward their peers, while chimpanzees are even more sophisticated, flushing out prey into ambush positions.

In a certain sense, all human tactics on a short enough timescale resemble pack behavior—think contact drills executed along predesigned templates, with no deliberate planning and only minimal communication. This is the obvious analogy for drone attacks, wherein fast-moving missiles shorten the decision-making cycle, requiring statistically-optimized responses.

True Swarms

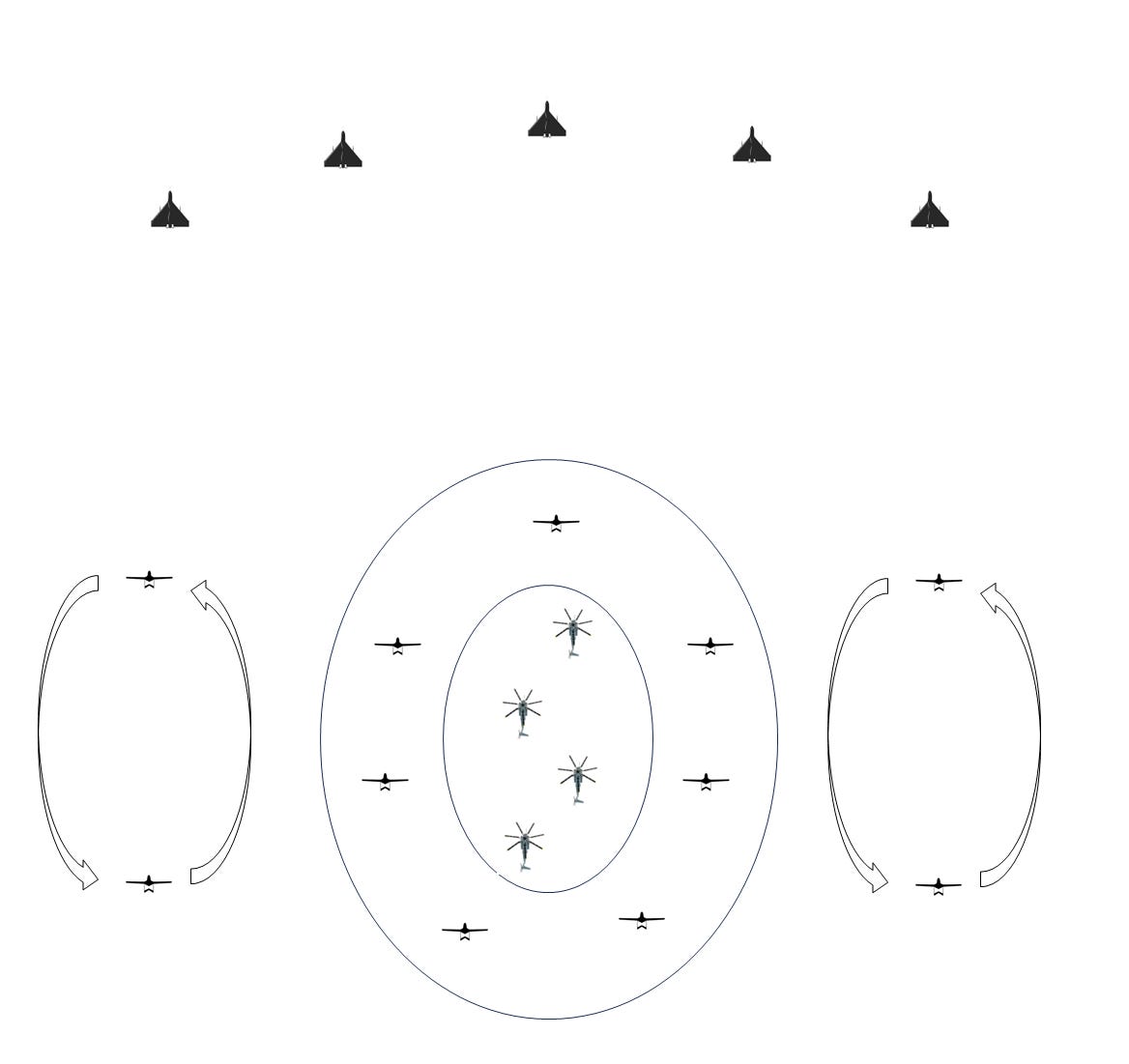

There is still a plausible use for UAV swarms; as with honeybees protecting their hive, it exists on the defense. Drone escorts forming a protective bubble around helicopters, proposed in the last piece, would effectively function as a swarm. Individual units would have to fly autonomously, with enough spatial awareness to maintain appropriate distance from the helicopters while ensuring that intercepts do not result in collateral damage.

In the event of hostile fire, they would have to estimate how many should respond in order to get a sufficient probability of kill without prematurely exhausting themselves, like bees escalating only up to a certain point. After every such engagement, the escorts would have to rearrange themselves to maintain all-around coverage with clear intercept lines.

I anticipate that we will see the rapid development of defensive swarms in the not-too-distant future. Just as naval ships no longer protect themselves with heavy armor and point defenses, but instead distribute air, missile, and subsurface defenses among several escort vessels, it is easier for air and ground platforms to disaggregate their own defenses. Drone swarms can be used to protect armored vehicles, radar sites, and any number of other high-value targets. The rate at which this is done may well determine how soon mobility is restored to the battlefield.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

For more information about the algorithm and its history I suggest:

https://www.red3d.com/cwr/boids/

Just a quick note, the decentralized swarm movement is also known as the Boids algorithm, an Artificial Life program developed by Craig Reynolds in 1986.