The Chain of Combat, Part 2

Political Jointness

In Part 1 on the chain of combat, we looked at a different way of classifying armed conflicts, based not on the scale of fighting or asymmetry of forces, but on the overall coherence of combat operations. This framework is useful for describing many conflicts Western nations have waged in the post-WWII and especially post-Cold War era: European nations’ wars of decolonization, America’s involvement in Vietnam and the Middle East, etc. It also helps explain a central paradox: how these conflicts often end in failure, despite increasing overmatch in conventional capabilities.

The Political Context

Military force is merely an instrument of policy, and all political actions must be coordinated in order to be effective. This is true even in large-scale wars where the military defeat of the adversary is the primary aim. Although political leaders usually grant their generals broad leeway, recognizing the unique and self-contained logic of combat operations, they must often overrule them when more pressing matters come to the fore. Questions of diplomacy, economy, and public support sometimes take priority over operational success, forcing generals to take actions that obey no higher military logic—a strategic-level break in the chain of combat, in other words.

One can say more broadly that breaks occur in the chain of combat wherever political and military questions become intertwined. We see this across the entire spectrum of conflicts. Every counterinsurgency campaign must wrestle with a direct tradeoff between military expediency and broader political objectives at the lowest tactical level. Rules of engagement assume an outsized importance, and the split-second decision whether to shoot or not can be of decisive importance—it is no accident that the term “strategic corporal” was coined in such an environment. Other examples abound: whether or not to raid a particular village, which local leaders to work with, what sort of economic aid to provide.

Balancing the political and the military

It is not too great a leap to make the analogy between the coordination of political instruments and combined-arms or joint warfare. At the lowest tactical levels, the separate arms are synchronized to take advantage of their respective strengths: artillery suppresses, tanks and infantry assault, armor exploits. So too with the various service branches in joint operations: air and naval fires enable amphibious landings, which set conditions for follow-on land operations, and so forth.

In both cases, there is a single commander responsible for integrating these efforts at the point where they come together. The commander of an infantry brigade which receives artillery and tank attachments is no longer just an infantry officer, but a combined-arms commander; similarly, the commander of a joint task force is responsible not just for the mission of his own service branch, but of the entire joint force. In neither case is it a matter of one arm or service acting with the support of the others, but of a unitary force integrating all the means at its disposal to accomplish the objective.

What we might call political jointness—something more than the cumbersome “whole-of-government approach”—similarly entails unifying the levers of political power under a single official. This obviously works well in full-scale wars, wherein national leaders form cabinets to coordinate industrial policy, alliance-building, embargos, and military operations. In the American example, Lincoln and Roosevelt come to mind. What, then, explains the failures in Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan—even though these were high political priorities?

Arguably, these smaller ventures failed precisely because they were high presidential priorities. Coordination of efforts occurred at the wrong level. There was no single person beneath the president himself who 1) was tasked with formulating a coherent strategy and 2) had direct tasking authority over all national assets in theater. Although there were various mechanisms for the military and various federal agencies to coordinate action on the ground, each organization’s requests and recommendations were ultimately advocated for by their agency heads at the National Security Council—a cabinet-level body—which drew up the strategy for these conflicts. This was then implemented by the various agencies in theater, where their separate organizational interests often took priority over the national mission. The military, as the main effort, had the biggest role in shaping strategy and maintained some direct control over other national assets; but it had neither the mandate nor the expertise to understand the full political problem.

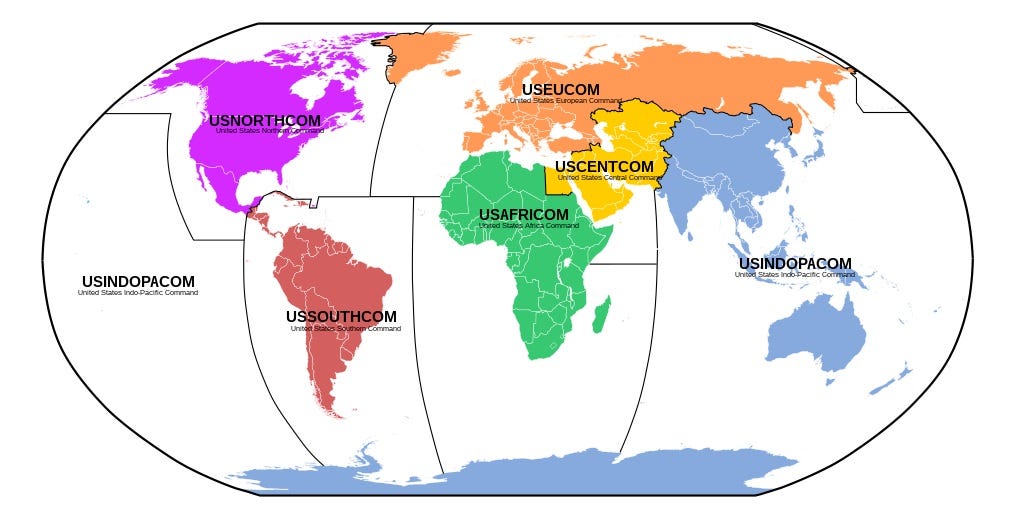

This political situation in fact resembled US joint operations prior to the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986. Before these reforms, individual service chiefs had ultimate operational control over their respective elements, and the commanders of joint task forces tended to act according to their own service’s priorities at the expense of the joint mission. The chain of command introduced by Goldwater-Nichols bypassed the service chiefs entirely, placing all operational forces under one of six geographically-aligned combatant commands. The bill also put a great emphasis on jointness, taking steps to ensure that joint task forces were better integrated and organized around a common objective. Combatant commands created entire staffs familiar with the intelligence picture and operational problems unique to their region, allowing commanders to formulate operational plans for anticipated conflicts and advocate for the force structure and allocation he would need to execute them.

Political jointness would entail a similar unity of effort: a single official with direct tasking authority over all national assets in country, supported by a staff to advise him on employing military, diplomatic, intelligence, and economic assets. Pure insurgencies are more complicated still: if policy instruments should be synchronized as close to the break in the chain of combat as possible, then counterinsurgencies must do so at a very low tactical level. Local conditions vary considerably, requiring very different combinations of force, economic inducements, and alliance-building depending on the province or even municipality.

The military itself recognized the convoluted political nature of this problem in Iraq and Afghanistan, and made some efforts to adapt. It expanded its capabilities in civil affairs, information operations, and the like. Great effort went into writing JP 3-24, the DoD’s manual on counterinsurgency. But armed force was only one tool in a much larger mission, and not even the most important; giving the military responsibility for counterinsurgency is as sensical as defining “combined arms” as a task for the artillery. Any serious attempt at counterinsurgency would place the full spectrum of political tools in the hands of relatively low-level officials, even if that meant placing civilians directly above brigade- or even battalion-sized elements.

None of this is to say that Vietnam, Iraq, and Afghanistan were ever winnable—all three were executed under bad assumptions, witnessed manifold planning failures, and set unrealistic objectives. This is only to point out a more general problem of diffusing responsibility. It inevitably allows broader strategic aims to color planning assumptions, the siloing of efforts, and the shifting of blame between agencies.

The Other Side of the Coin

If Western nations have had a dismal track record in the small wars and insurgencies of the past century, it owes at least in part to the striking success of various Marxist movements. Even when completely outmatched militarily, they were able to organize and expand until strong enough to undertake more ambitious objectives. Indeed, Marxist methods of organizing were arguably designed precisely to address the political-military problem, with party cadres operating alongside guerrilla leaders to ensure that military actions supported the movement’s broader goals.

Among the most successful of these leaders was Mao, who articulated a three-phase approach for revolutionary warfare. The first involved building networks in remote or inaccessible areas, indoctrinating the peasantry, and recruiting fighters; the second involved larger-scale guerrilla actions from a safe base of operations; and the third was an all-out conventional war. In all three phases, political commissars were assigned to military units—although this violated the principle of unity of command, it gave the movement’s leaders a better handle on political questions such as alliances, popular support, and long-term strategy.

Unsurprisingly, this and similar formulations fared less well farther up the chain of combat. Commissars had no natural role in the large-scale combat operations of World War II, and they interfered so much that Stalin abolished the position in October 1942. By this point, their primary role had in any case become to ensure Red Army generals’ loyalty, so they were easily replaced by other officers who fulfilled that role.

The examples of the past illuminate the problem of political jointness, but do not offer easy solutions. It is a question that all military operations short of full-scale war have to deal with, and one which will only grow more complex with time. As with any large-scale endeavor, synchronizing and coordinating efforts is the most difficult part of planning. Different governments and non-state actors face very different problems in this regard, making it hard to predict what will work in various conflicts. But those who do it well will always have an enormous advantage.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.