The Northern Front: Trench Warfare in the 18th Century

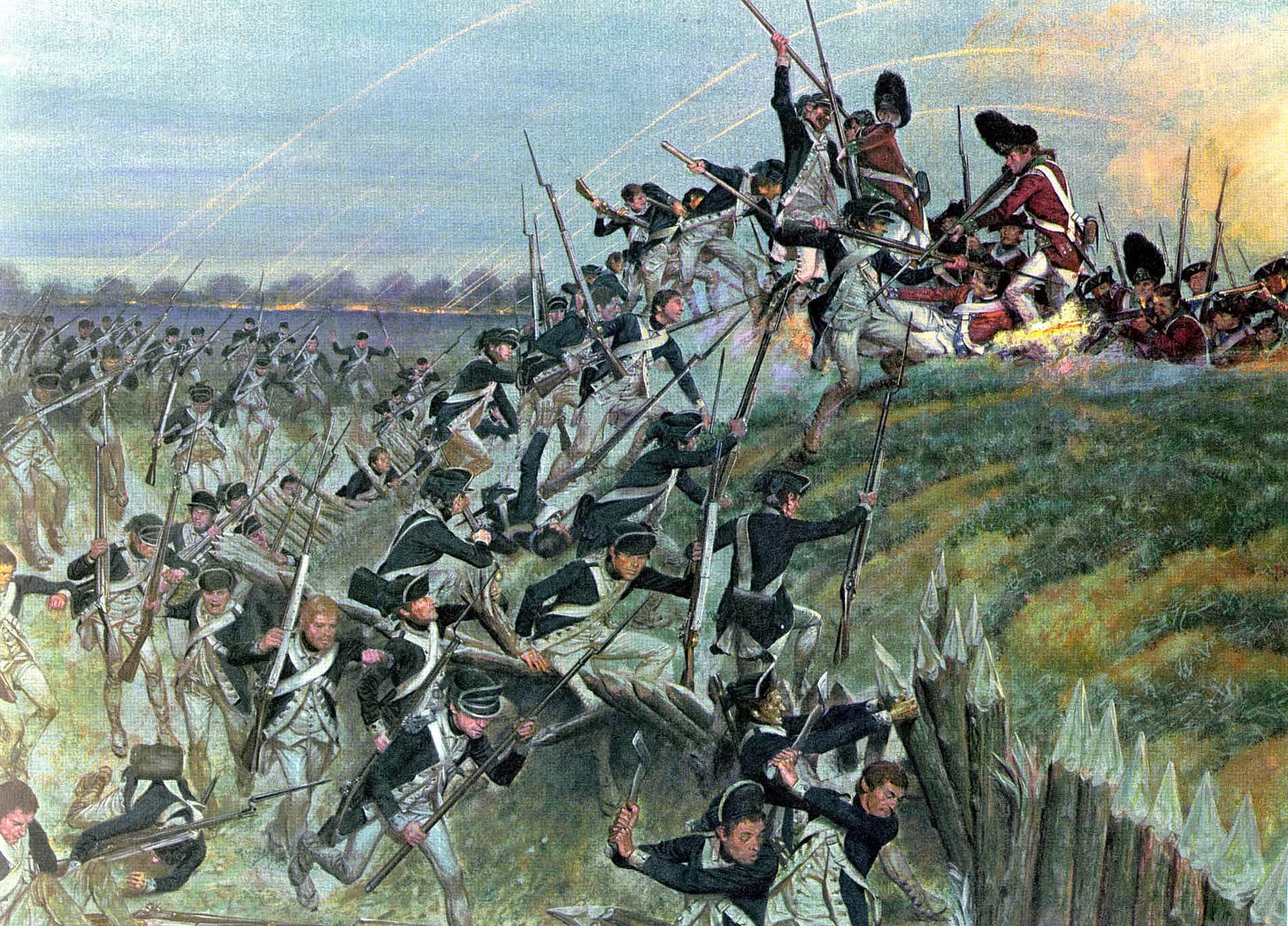

Artillery flies over the heads of soldiers huddling in the trenches as they steel themselves for what is to come. These men have fought countless similar actions over the past few years, each time hoping to pierce the enemy’s lines and bring the war to an end. But each time their hopes are dashed: they make only incremental progress at great cost in blood, and the enemy always manages to fall back on even stronger positions. Lulled by the sounds of their guns pounding the enemy’s positions, the soldiers’ reveries are interrupted by the sergeant’s whistle. With a shout, they leap as one over the top and charge across open ground. Many are cut down in the hail of fire that greets them, but most make it to the enemy trenches. Their firearms become melee weapons as they stab, shove, and club the defenders, cries in English, French, and German rising above the din.

The First World War is usually seen as a singular folly, a war made uniquely bloody by the confluence of technology and mass mobilization. It is the archetype to which all other periods of static trench fighting are compared, whether in Korea or now Ukraine. Yet not only was it not the first such war, it was not even the first such war in that region. The scene above describes a conflict waged on Flanders’ sodden fields two centuries before the guns of August erupted.

A World War

The War of the Spanish Succession (1701-14) was the last of the great wars of Louis XIV, fought by millions of soldiers across several continents. It broke out when the French king’s grandson, Philip of Anjou, was chosen to succeed the last Habsburg king of Spain. This threatened the political balance of Europe: Spain controlled much of the Low Countries and Italy, not to mention a vast colonial empire, threatening to give the Bourbon dynasty unassailable hegemony. The Austrian Habsburgs, who maintained their own claimant to the Spanish crown, declared war immediately, joined the following year by England and the Dutch Republic following a series of diplomatic missteps by Louis.

The Grand Alliance, as the anti-Bourbon coalition was called, made the Spanish Netherlands (modern Belgium) a major theater of operations. It was there that all their interests converged: Dutch anxiety over their southern border, English desire to keep the Channel ports out of French hands, and Austrian claims to traditionally Habsburg territory. It also presented the best invasion route into France, which offered to secure all their war aims at once.

The Lines of Brabant

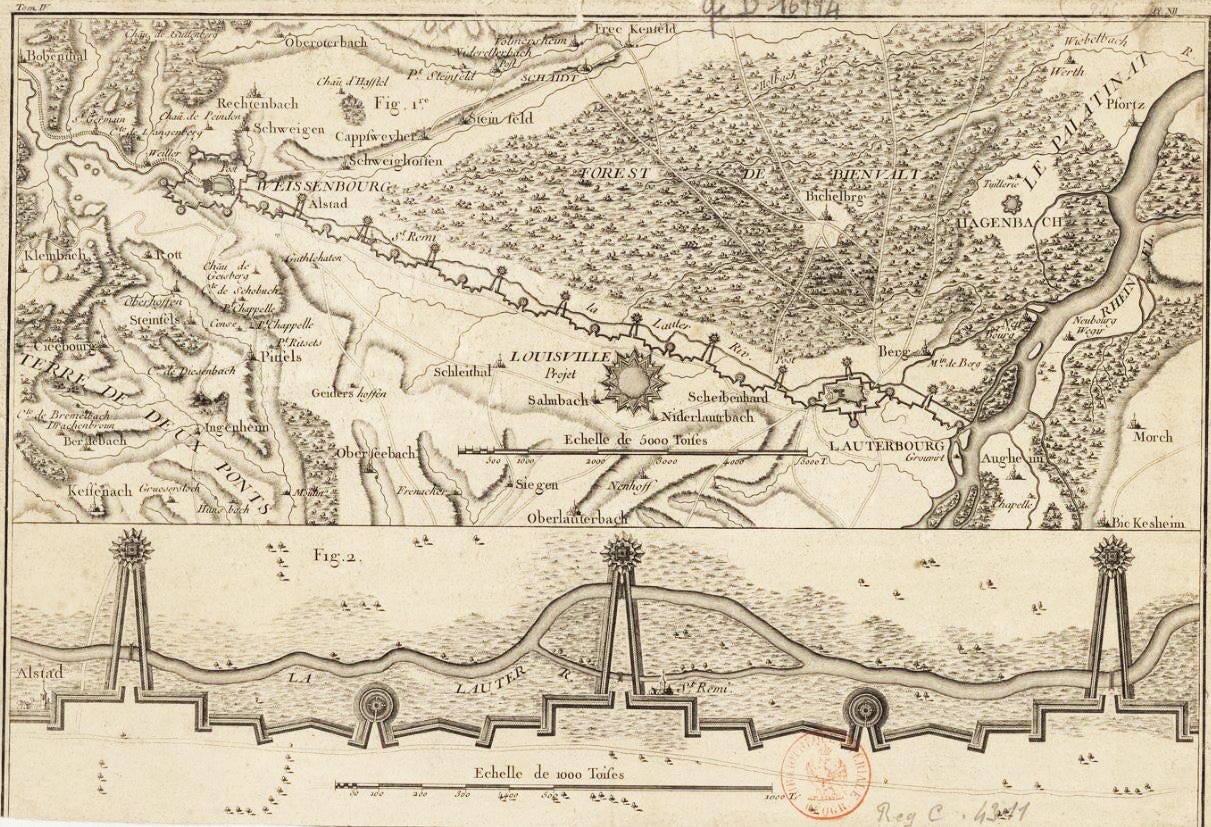

The French, for their part, remained on the defensive in the north, conserving their offensive strength for other theaters. To this end, they constructed the Lines of Brabant, a long system of ditches, ramparts, and palisades. Such defensive lines were common in the 17th and 18th centuries. The French and Germans maintained several along the Rhine frontier, each at least fifteen kilometers long, and there were other such lines in the Black Forest, Low Countries, and northern Italy.

None of these compared to the defenses built in 1701, however. The Lines of Brabant stretched nearly 130 kilometers through modern Belgium, from Antwerp on the Scheldt to the Meuse near Namur. They were augmented by another set of fortifications that ran from the opposite bank of the Scheldt to the coast. It was ideal country for this. The Low Countries had long contested ground, dotted with many fortresses that could be integrated into the lines. The land was also cut through with rivers and canals which formed part of the barrier.

These waterways also made it possible to amass large armies in the region. They irrigated fertile farmlands and served as corridors for provisions and equipment to the front—both sides regularly maintained upwards of 100,000 soldiers in theater. Although these numbers were nowhere near sufficient to man the entire front, the French garrisoned and patrolled the quieter sectors. If a breakthrough attempt was detected, detachments would be rushed to man the lines until the main army arrived. The effect of the entrenchments was therefore largely indirect: it was their defensive potential that prevented the Allies from pushing forward. To put it in Mahan’s terms, it was the army-in-being that created the front, not the entrenchments alone.

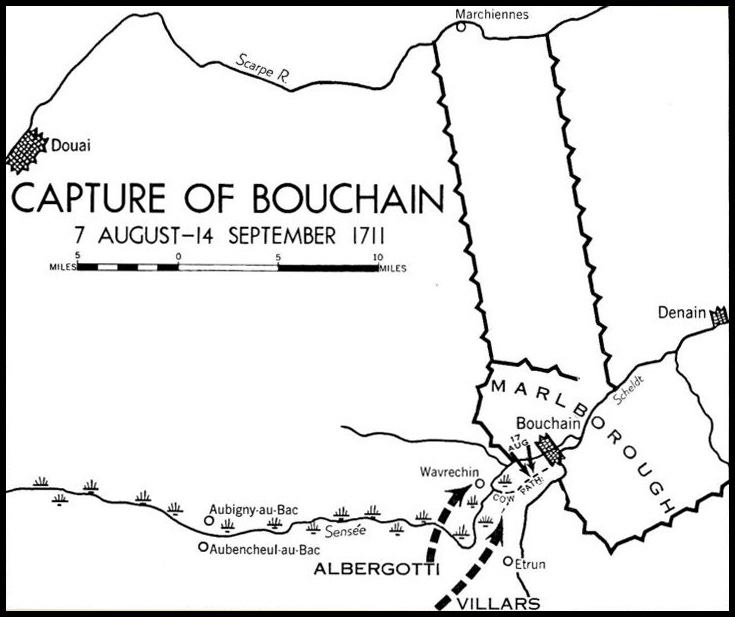

In the event that an attacking army did manage to break through, it could not simply charge forward. A mishap early in the war showed the dangers of trying to barrel through. In 1703, the Allies launched diversionary attacks at two points along the Lines of Brabant so that a Dutch corps could break the lines west of Antwerp and attack a fortress on the coast. The supporting attacks went badly, however, and the Dutch, at risk of being cut off, were forced to retire. This left the Allies with little choice but to take a slow and steady approach, capturing one fortress at a time to secure their advance.

Advancing The Front

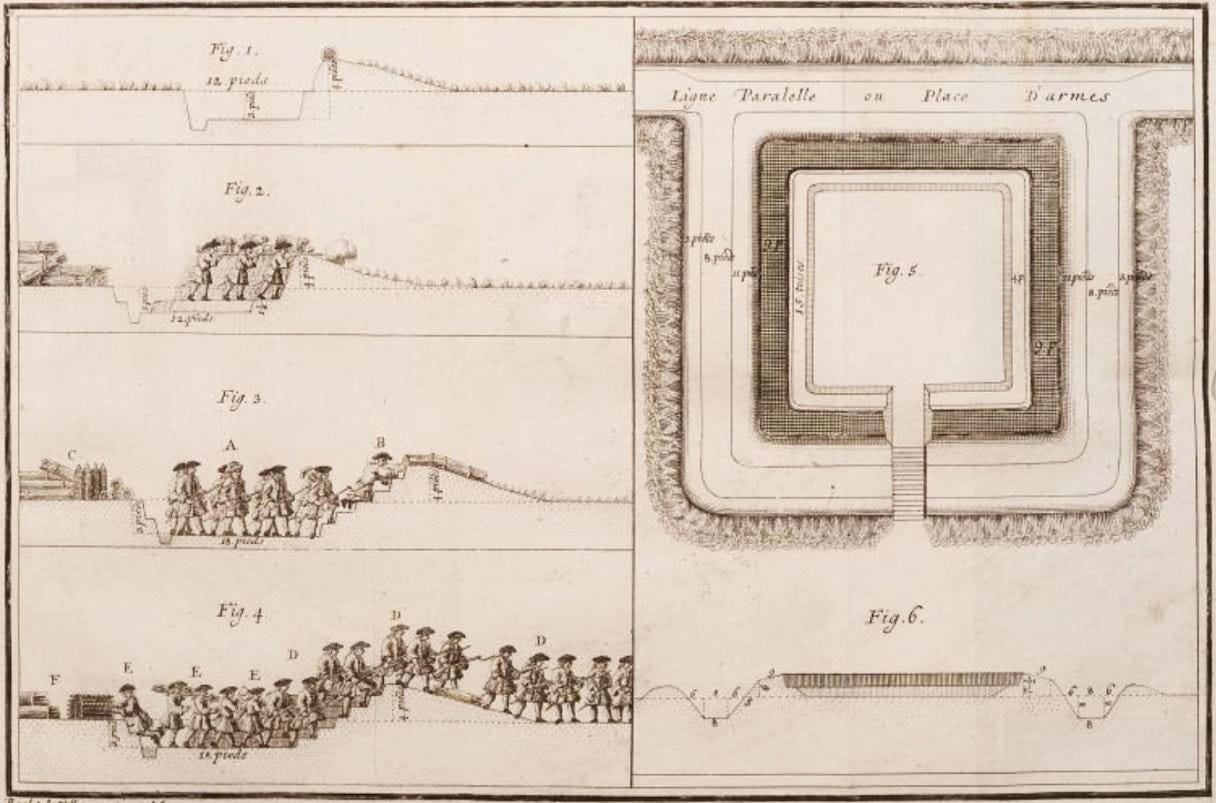

The art of siegecraft had been perfected by the 18th century. The bulk of the besieging army was assigned to the covering force, which entrenched itself across avenues of approach to prevent enemy interference. Engineers in the siege force then dug a series of parallel trenches progressively closer to the walls, which served as firing positions for the artillery and cover for the infantry to assault the outworks (many of which were just trenches protected by a low rampart).

This was slow and painstaking work, during which soldiers and workers were exposed to the constant threat of gunfire and counterattacks on their own trenches. When the time came for the final assault, cannons and mortars battered the walls to create a breach, which the infantry attacked with grenades, muskets, and bayonets into a spray of grapeshot. In a quite literal sense, the heaviest fighting in the Low Countries was trench warfare.

The similarities extended to the operational level. The elaborate system of depots and riverine supply routes resembled the rail-bound logistics of the First World War, capable of provisioning large forces along a static front but unable to sustain a rapid advance. Once the attacking army secured a lodgment, it had to widen the penetration and build out its depots before moving deeper into enemy territory. This gave the opposing army plenty of time to counterattack; failing that, the defenders could still fall back to new positions—the French often built redundant lines in vulnerable sectors. This drastically limited offensive potential, resulting in a protracted, attritional grind.

Breakthrough

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.