The Utility of Military History

Read and reread the campaigns of Alexander, Hannibal, Caesar, Gustavus Adolphus, Turenne, Eugene, and Frederick. Model yourself on them. This is the only means of becoming a great captain, and of acquiring the secret of the art of war. Your own genius, enlightened by this study, will learn to reject all maxims contrary to the ones held by these great men.

-Napoleon Bonaparte

Is there any practical use to studying pre-20th-century military history?

It is often argued that a responsible citizenry should be educated in the history of a nation’s wars. The evolving relationship between military and society gives us a useful framework for political debates; and at the highest levels of national strategy, there are plenty of universal lessons to be learned about alliances, economic policy, and wartime leadership. But all that lies beyond the practice of warfare itself. Does history serve any useful purpose for the military professional?

To modern ears, Napoleon’s advice sounds quaint. The very word “maxim” carries a whiff of the archaic, and the methods of the gunpowder age are long outdated—it is probably impossible to find case studies one could describe as useful dating before the Second World War. And all that notwithstanding, his advice rings a bit glib: history is complex and messy, not at all easy to extract lessons from. Even before Napoleon’s era, it was an unreliable guide which often led men astray.

This was already apparent in the Renaissance, a time when it was believed that most worldly knowledge worth having could be found in the classics. Yet Greek and Roman models proved at best irrelevant and at worst detrimental on the battlefield. Machiavelli’s treatise The Art of War was filled with impractical advice taken from ancient writers and was mostly ignored by his contemporaries—in one famous episode, a mercenary captain deflated his pretensions by showing him incapable even of commanding troops on a parade ground.

One of the finest authorities on Renaissance warfare said the following:

In the actual practice of the art of war at this time it is hard to discover any indisputable outcome of classical teaching. Tommaso Carafa, who commanded a Neapolitan force against the French in the campaign of 1495-6, is said by Paolo Giovio to have lost a battle by disposing his troops in the form of a crescent, "according to the custom of the ancients," and the historian adds that such imitation of the ancients had often been the undoing of Italian commanders. The same writer implies that the lines which Prospero Colonna dug for the defence of the citadel of Milan were modelled on those which Julius Caesar dug at Alesia, but it seems very probable that Giovio was led to suggest this classical inspiration by the obvious resemblance between the two works. A more transparent instance of a historian seeing studied imitation where there was only accidental similarity is Merula's remark that Prospero Colonna was indebted to Roman teaching for his fortified camps and Fabian tactics [Ed: these were both very common medieval practices].

-F.A. Taylor, The Art of War in Italy, 1494-1529, ch. 8.

If naïve imitation of the past was the worst consequence of Renaissance humanism, a very different type of error resulted from the revival of enthusiasm for ancient warfare in the nineteenth century. This was the great age of German classical philology, which helped give birth to military history as a formal discipline. Scholars and soldiers alike produced detailed case studies of past battles, often with explicitly practical ends.

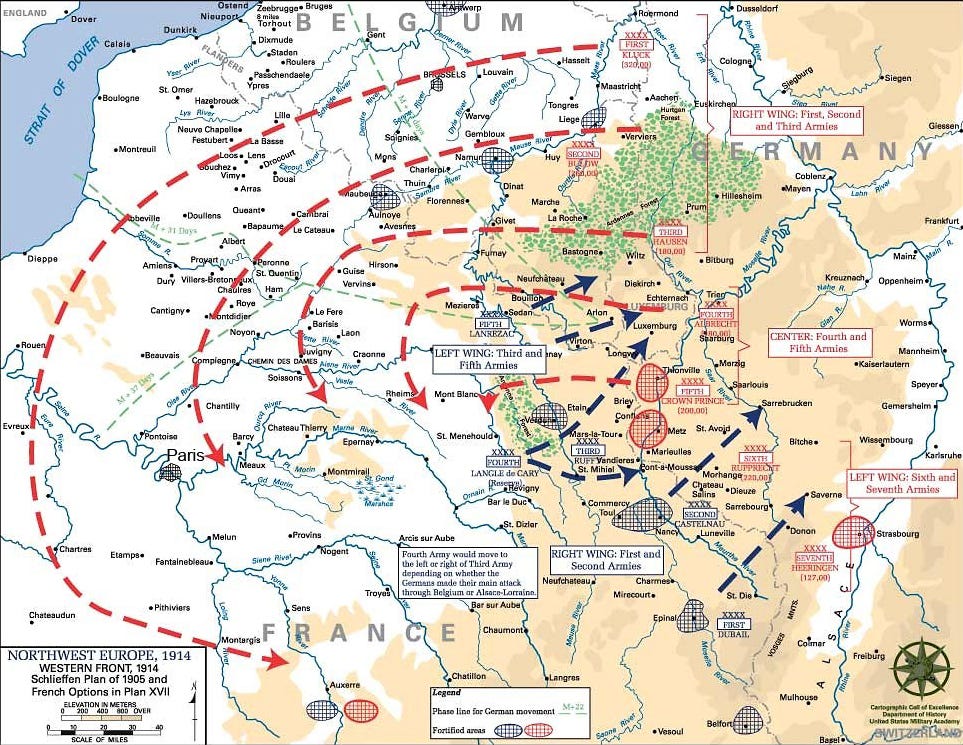

The most famous of these was Count von Schlieffen’s study of Cannae, which furnished the model—or at least justification—for his war plan against France. He trawled history for examples of other “Cannaes” to show how large battles of annihilation could be won. Although Schlieffen fundamentally misunderstood Hannibal’s mechanism of victory at Cannae, he cannot be accused of repeating Carafa’s mistake, as his discussion of more recent battles showed far more consideration of the particulars. His real error was different: an obsessive focus on a singular principle which he thought Cannae embodied, one he believed necessary to winning a rapid and crushing victory.

Other nineteenth- and twentieth-century writers followed this pattern, using of historical examples to illustrate general precepts. Victories of the Roman legions showed the value of flexibility, as battles such as Cerignola did for combined arms; commanders such as Frederick the Great were held as models of the indirect approach, just as Napoleon showed the importance of speed and decision. Many of these showed quite successfully that however much the face of war has changed over the centuries, there are undeniably general patterns which remain constant.

Yet this presented another difficulty: how to make use of such general rules? It is not easy to determine a specific course of action from broad guidelines, and there may always be other factors which prove more important. One’s own situation may differ from past examples in subtly important ways—in organization, training, mobility, logistics, and so forth—which render comparisons invalid.

Schlieffen’s own case serves as a warning of this. The outcome of Germany’s 1914 offensive owed less to the conceptual validity of annihilation by encirclement than it did to the impossibility of executing such a maneuver with a logistically-demanding army supplied mostly by animal power. By focusing on a single principle, he neglected other factors which proved much more decisive.

Any use of the past, whether Carafa’s literal-minded imitation of ancient battle formations or Schlieffen’s pursuit of a singular battle of annihilation, runs into this fundamental problem:

A general pattern observed in history cannot be applied universally.

This is of course true not just of historical examples but of any general rule. Most modern armed forces indoctrinate their servicemembers in some variation of the principles of war, sets of guidelines for the conduct of operations: maneuver, unity of command, initiative, and so forth. These are never hard-and-fast rules and are not taught as such, but rather important factors which must always be considered and often entail difficult trade-offs—between mass and economy of force, for instance, or between surprise and simplicity.

And these principles are indeed universal. As much as modern combat differs from antiquity, the Middle Ages, or the pike-and-shot era, any experienced commander or staff officer today could recognize the dynamics operating in past wars; examples from history are useful illustrations of these principles, and are the most common use of history in modern military instruction.

But that is not the same as studying military history. Case studies are necessarily limited in scope, usually intended as instructional devices to draw out a certain point. Their framing makes it easy to pick out the material factors from the full mess of reality, whereas a true study of history must engage with that mess. Although this follows Napoleon’s advice to develop a sense of the best maxims, it is still somewhat unsatisfactory.

As with anything, the rules of war only truly begin to make sense with experience. It is one thing to understand a principle intellectually, quite another to have a feel for how things work where the rubber meets the road: what a principle looks like in practice, how it interacts with other principles, how it shouldn’t be applied. With this in mind, we can reframe our original question…

Can history ever serve as a substitute for experience?

The answer lies in the overlooked first part of Napoleon’s exhortation. He did not recommend the study of battles, but of campaigns.

Campaigns before the twentieth century are in many ways the opposite of case studies. The latter thrusts us into a specific scenario, at a certain time and place, with a certain number of troops and resources, and with an immediate objective in mind. In set-piece battles of yore, as in modern operations, most of a commander’s mental efforts took place before things even begin: gathering an intelligence estimate of the enemy, selecting the best scheme of maneuver, matching troops to task, arranging logistics, etc. Once the action commenced, there were only a limited number of decision points where he could influence the course of events—to grossly simplify, the results came down to a series of rolls of the dice. This naturally focuses our attention on the mechanism of victory: what predetermined course of action gives the best probability of success in a scenario, accounting for a limited range of possible enemy responses.

Campaigns, on the other hand, were fundamentally more open-ended. When armies marched out of their winter cantonments for the season, they did not always know in advance which fortress to attack or where to fight a decisive action. Even when they did have a definite objective in mind, the entire challenge lay in establishing the conditions which would allow them to accomplish it; just as often, however, enemy action or the accidents of fate forced them to reevaluate their entire plan.

This open-endedness created a very different decision-making structure. Plans had to account for a far greater degree of uncertainty, and the ability merely to remain in the field as a coherent force was at least as important as the pursuit of an objective. Sheer accident could moot one’s present course—Napoleon’s own staff was famous for issuing a steady stream of countermanding orders as circumstances evolved—and it was quite common for armies to stumble into a decisive engagement without realizing it. In short, decision-making was a far more continuous process.

This remained true even when both sides were clearly heading toward a decisive clash. Most of a commander’s focus had to remain outside the object itself: heeding his own vulnerabilities, considering the enemy’s intervening actions, ensuring that he was not detracting from his own efforts elsewhere, and getting enough men and supplies to the right place. And looming above all that was the risk of failure: what would the immediate consequences be? Was there a safe line of retreat? How would failure change his overall position? Naturally enough, the decision whether to engage in battle was just as important as the battleplan itself.

These questions shine through in narratives and memoirs from past campaigns. Many sources record war council debates over objectives, contingencies, marching routes, and supply considerations. It is by engaging with these debates and working through the decision-making process that a student can develop an intuition for the principles of war—not as a list of rules, but as a way of conducting operations in the face of uncertainty and risk. Even when the sources don’t reveal a commander’s thoughts, it can be just as instructive to try to figure out what he might have been thinking, or whether a failed action might have been somewhat justified by some non-obvious factor.

At its best military history is like a problem set with a partial answer key.

This can never be a full substitute for first-hand present-day experience, but it can make one more receptive to that experience. And as the old schoolteacher’s saying goes, you only get out of it what you put in.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

I hope you continue my dear friend. I enjoy following you

One of the reasons that the Prussians recognized kriegspiels as a tool with which to prepare an army for war was that the games offered Prussian officers the opportunity to practice making decisions and seeing the consequences of those decisions. Military history (obviously emphasizing good military history) offers similar opportunities as the reader follows a past commander's series of decisions from planning to execution to building on the outcome.