Venice and the Problem of Grand Strategy

The last two decades of the 15th century saw the Venetian empire at its peak. Domination of the Mediterranean spice trade turned Venice into the most important commercial hub in Europe, drawing a steady stream of gold and silver into its coffers. This wealth was built upon sea power: the Venetian navy was the strongest of any European power, outfitted with the best ships and sailors in the world. At home, Venice enjoyed domestic tranquility, suggested by the name La Serenissima, governed by republican institutions upheld as ideal by Renaissance scholars.

If Venetians’ fortunes were at their height, they were all too aware of how far they had to fall. Threats loomed to the east and west which might knock them off their perch. Their complete dependence on the maritime trade made them vulnerable to the rapid growth of Ottoman naval power, while her modest land empire was an inviting target for Europe’s growing powers.

Nevertheless, Venice averted any sudden catastrophe. Although nowhere near strong enough to compete head-on with the centralized states that were then emerging, her inevitable decline was long and steady, lasting a full three centuries. It was not until 1797 that she finally succumbed to the tide of the French Revolution, to which no European state was immune. The ability with which Venice managed this, emerging as well as could be expected from such a time of crisis, makes it a fascinating case-study for the problem of grand strategy.

Venice and Grand Strategy

Grand strategy is profoundly different from the other levels of war. As a working definition, it is the application of the whole of a state’s resources towards the furthering and maintenance of its interests. This requires the coordination of many different sectors: military, industrial, economic, media, etc. Yet except in the most totalitarian societies, the state does not have the same authority over these separate elements that military leaders do over their subordinates. Political leaders might incentivize and encourage industry to invest in certain key sectors, for instance, but they cannot force it. Grand strategy is more a problem of management and coordination than it is command.

And that is just the execution. Merely formulating grand strategy is a whole other set of negotiations: if grand strategy is supposed to serve national interests, who gets to define those interests? Political leaders are vested with nominal responsibility, but they are tasked with protecting the interests of their constituents. This is obvious in a modern democracy, but it is also true of monarchies in the past, where interests and power blocs always had to be satisfied. The formulation of grand strategy is therefore in some sense a political compromise among all the factions within a state.

This was a great advantage for the tight-knit oligarchy which ruled Venice. The city’s entire economy was oriented around maritime commerce—the great noble families engaged in trade, while the commoners were merchants, sailors, dockworkers, shipwrights, etc—and all Venetians recognized the need to keep the sea-lanes open and protect foreign trade. Beyond this natural convergence of interests, Venice developed strong institutions to suppress factionalism within the elite. From early on, the municipality was governed by republican institutions: a representative body composed of eligible citizens, and a chief executive, the doge, who was elected for life. Sometime in the 12th century, elections were limited to the Great Council of all adult male patricians, over the following centuries this body placed increasing restrictions on the doge’s power: he was required to consult appointed advisers on all decisions, while certain executive powers were devolved to various committees.

Effective power was held by a few dozen patricians who dominated these bodies; they were carefully groomed for their roles over long political careers, narrowing and homogenizing the decision-making process. This helped them avoid the fate of Genoa, another great mercantile power which was confounded by frequent and bloody upheavals. Whereas the great Genoese houses pursued their own interests at the expense of the common interest, Venice could chart a deliberate course years and decades in advance.

On the Eve of Empire

The great irony is that the Venetians came into their empire wholly unexpectedly. Up to the 13th century, they had built a modest base of power by extending control over the Adriatic Sea; this made them useful to the Byzantines, who granted them generous trade concessions in return for naval aid.

Constantinople became the main source of Venice’s commercial wealth, but in the wake of the First Crusade her ships began extending their routes to the eastern stretches of the Mediterranean. In return for naval aid, she gained trade concessions in the newly-conquered port cities of the Levant. These consisted of single squares or neighborhoods by the harbor—not true colonies, but together they constituted a network of friendly anchorages where they could do business.

Venice’s priorities up to that point were roughly:

Security of the city itself

Security of the Adriatic Sea, through which all her commerce had to pass

Relations with the Byzantine Empire, her greatest trade partner

Trade with the Levant

The Levantine trade became relatively more important in the 1170s when relations with Byzantium went through a rough patch. An emperor imprisoned all Venetian merchants residing in Constantinople and impounded their goods as punishment for their attack on the Genoese quarter. Venice launched an ill-fated retaliatory expedition, and after a few more years of hostilities the two made peace, but the entire episode soured Venetian-Byzantine relations. It was against this background that the French and Venetian forces of the Fourth Crusade conquered Constantinople, leaving the maritime republic of the Adriatic with a true empire.

The Conquest of Byzantium

The story of the Fourth Crusade is a convoluted one, involving a planned expedition to Egypt for which the would-be Crusaders contracted a large Venetian fleet. As the date of departure approached in summer 1202—and the bill came due—the knights realized that too few men had shown up, leaving them unable to pay for their passage. The Venetians kept them effective prisoners on the Lido until some arrangement could be made (halting trade to build a new fleet had been quite expensive), so Doge Enrico Dandolo brokered a deal: the Crusaders would assist Venice reconquer some rebellious cities on the Adriatic to recoup their costs, after which they would be taken to Egypt.

It was around this time that the expedition was approached by the son of a deposed Byzantine emperor, the victim of the latest coup in Constantinople. He offered an enormous payment—more than enough for the Crusaders to pay their debts—if they would help him gain the throne. This they agreed to do, besieging Constantinople in July 1203 and successfully installing their client on the throne as Alexios IV. Years of improvidence had drained the Byzantine treasury, however, leaving him unable to pay his debt. After a protracted period of negotiation, the Crusaders and Venetians realized that they were never going to get satisfaction, and thereupon decided to conquer the city outright and divide the empire among themselves. They laid siege to it the following spring, and on 12 April fought their way over the walls and subjected the city to a dreadful sack.

Per their prior agreement, they elected an emperor, who was given a quarter of Byzantine territory, while the Crusaders and Venetians evenly divided the rest (pending its conquest, that is). Dandolo selected the choicest bits for a maritime power: Crete, Negroponte (ancient Euboea), many islands and port cities around the periphery of mainland Greece, and part of Constantinople itself.

Managing the Empire

Coming so suddenly into a great empire could have easily torn apart the Venetian social fabric. Massive shifts in fortune offered infinite chances to ignite jealousies, upsetting the balance of power—even small inheritances tear modern families apart. They were somewhat aided by the challenge of taking actual control of these places: Venetian claims could not simply be asserted, but had to be secured by force. This required substantial investment by all who wanted to take part, making the prize less of a windfall.

The greater threat to domestic tranquility came in the following decades. The republic’s new empire made it easier for humble families to acquire massive fortunes in the overseas trade, creating a large class of new wealth. These new families shifted the balance of power within the Great Council, causing the nobility to restrict membership in the late 13th and early 14th centuries. New rules for electing a doge were also instituted during this time, creating a convoluted system which made it difficult for any one family to dominate proceedings.

Changing Currents

It was important for the Venetians to be able to present a united front to the outside world, as the Mediterranean was growing increasingly turbulent. European power in the Levant—and hence Venetian trade interests—was precarious following Saladin’s victories of the 1180s, which confined the Crusaders to a narrow coastal strip. The Byzantines retook Constantinople in 1261, and the last Crusader enclave fell to the Egyptian Mamluks in 1291.

The Venetian response was diplomacy rather than war. The great emporia of Constantinople and Alexandria, which saw the transit of vast sums of wealth, could only profit their rulers if merchants came to call; this made Venice an indispensable partner, whatever periodic squalls might trouble their relations, and after a few unprofitable years all parties managed to patch things up. The Venetians signed a new treaty with the Byzantines in 1268, and in 1302 they signed one with Egypt.

The more serious threat to Venetian prosperity came from their commercial rivals, the Genoese. Between 1256 and 1381, they fought a series of wars over control of ports and sea lanes, which posed a serious dilemma of grand strategy: how to balance commercial and military interests. The first of these wars broke out in the remnants of the Crusader states, where a shrinking pie made the competition for its division all the more vicious. The Venetians managed to wrest control of Acre, the principal port in the region, while the Genoese took refuge in nearby Tyre. At sea too, the Venetians generally had the better of it, winning several major fleet actions despite being outnumbered.

Yet this did not automatically translate to a victory for the Venetians. They adopted a convoy system to protect their trade fleets, requiring all merchant ships to travel in regularly-scheduled voyages protected by 15-30 galleys. Genoese merchant fleets sailed unprotected, but because Venetian warships were tied up with escort duties, they were unable to intercept them. Genoese warships and privateers, on the other hand, were free to prey on large concentrations of Venetian merchant vessels when the opportunity presented itself—they captured one convoy in 1264 after luring away its escort.

The competing strategies were a classic example of naval control vs. commerce raiding, of the sort the British and French engaged in during their long contest of the 17th and 18th centuries. The outcome in this case was not the same: despite racking up a number of victories at sea, the loss of commerce proved far more expensive for the Venetians than the Genoese—indeed, the war was becoming profitable for Genoa in its later years, and they did not agree to peace until 1270.

A Growing Rivalry

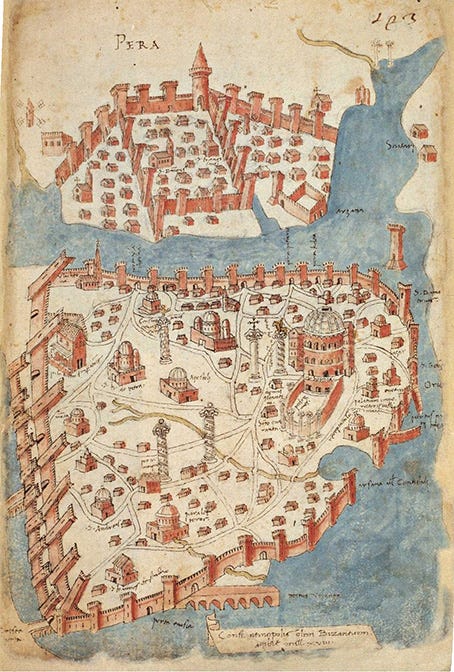

Overall Genoese fortunes were in the ascendant in the later 1200s, posing an increasing threat to Venice. They had formed a strong alliance with the Byzantine court during its time in exile from Constantinople, and upon the city’s recovery were granted possession of Galata, a suburb on the opposite side of the Golden Horn.

This was effectively a town in its own right and had its own harbor, giving them a stopover to expand its trade links in the Black Sea—the Mongol conquests of Eurasia had opened up the northern land routes from China, making the Crimea a competing source for goods that had recently only come through Egypt and Syria. Then in 1284, they crushed the third-richest merchant republic, Pisa, giving them a virtual monopoly in the western Mediterranean, which they extended into the Atlantic as far as Flanders.

Yet the Venetian position was still strong. She retained most of her Byzantine conquests, which provided ample stopovers between the home city, Constantinople, and the Levant. Venice itself was becoming a center of European trade in raw materials, and its nascent glass industry was fueled by cargo ballasts of soda ash and high-silica sand carried from the East.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.