Air-Mechanization, Part 1: An Obsolete Concept Whose Time Has Come?

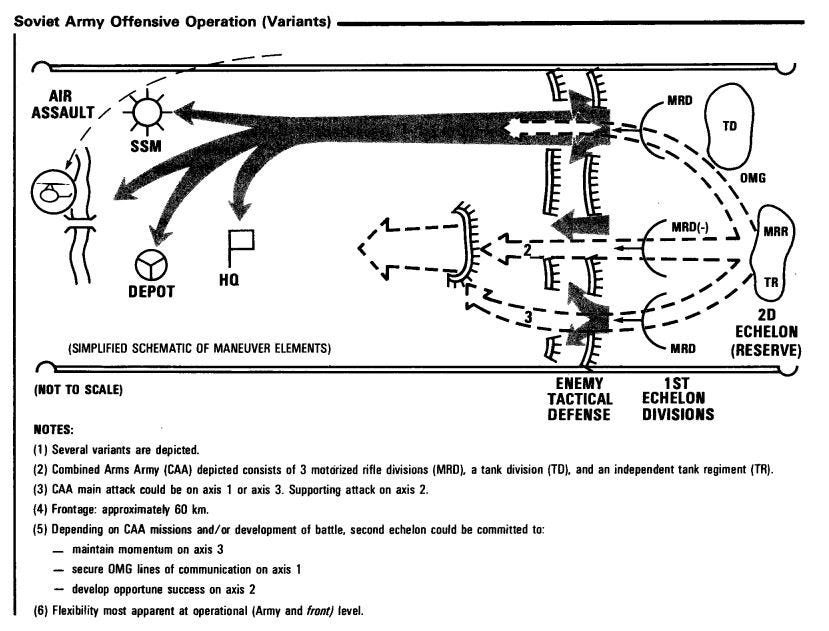

The 1980s promised a new era for helicopters. Armies on both sides of the Iron Curtain envisioned air-mechanized forces as the logical extension of World War II’s armored spearheads, thrusting faster and farther into the enemy’s operational depth than ground-based units. Attack helicopters armed with the latest-generation anti-armor missiles were to be the airborne equivalent of tanks, paired with assault helicopters carrying light mechanized forces—flying IFVs.

The concept was not entirely new. Every leading military experimented with parachute insertions during the Interwar years. These efforts, which continued through the 1970s, experimented with air-droppable tanks, IFVs, and artillery. What these platforms lacked in protection and firepower was to be compensated by their ability to strike far into the enemy’s undefended depths.

There were drawbacks, however. Parachute drops disperse forces over a large area, giving the enemy several hours to respond before a force of any size could concentrate. This makes it difficult to execute without nearby supporting ground forces, and drops were only rarely successful at great depths during World War II.

The helicopter offered an apparent solution. It allows several units to converge on a single point, so that troops can fully deploy within an hour of boots hitting the ground. After helicopters proved their basic viability in Korea, they were used extensively for tactical air assault missions in Vietnam, and were soon to be used in Afghanistan and the Falklands. This provided the template for heliborne assault on longer-range objectives, integrated into large-scale mechanized operations.

This synthesis appealed to prevailing thought on both sides of the Cold War. By the late 1970s, the Soviets were contemplating non-nuclear offensive strategies, which required high-tempo attacks to maintain their momentum. Heliborne insertion allowed the breakout force to preempt the formation of new defensive lines by seizing key bridges and airfields, where they could hold off enemy reserves until ground forces caught up. The Americans were meanwhile developing AirLand Battle, which sought to counter such offensives by disrupting second-echelon forces with strikes deep to the rear—air-mechanized assaults were an obvious candidate for this.

It was the Soviets who took the concept of air-mechanization the furthest. In the late 1970s, they created the first dedicated airborne brigades with organic lift at the army-group level, capable of inserting several battalions at great depth. These were still foot-mobile once on the ground, so planning considerations demanded that breakout forces link up with the airborne within six hours of insertion. The introduction of a new heavy-lift helicopter, the Mi-26, offered a possible solution: the Soviets experimented with corps-sized formations which could insert lightweight BMDs and 2S9 self-propelled mortars.

American interest in large-scale “vertical envelopment” took concrete form in 1974 when the 101st Airborne Division was converted to air assault. These formations were aided by the introduction of the Blackhawk into service in 1979, capable of transporting both infantry and 105mm howitzers.

The US never went as far in developing AFVs which could be delivered by helicopter. American strength in air-ground integration, meanwhile, combined with the Soviet armor threat, drew the new Apache into more of a tactical role as a tank-killer—at the same time that the 101st was being converted to air assault, the 6th Cavalry Brigade was reconstituted as the first air cavalry unit.

Air assault was nevertheless employed to great operational effect in Desert Storm, when the 101st Airborne conducted interdiction operations deep behind Iraqi lines. The US Army continued to develop ideas around air-mechanization through the 1990s with the Army After Next program, which looked at developing light-weight AFVs that could be inserted by helicopter, or at least delivered to assault troops via C-130s on unimproved airstrips.

This changed after 2001. The helicopter’s combat role in GWOT was mostly limited to tactical mobility and close-air support. Without any major developments on the Russian side, it appeared as if air-mechanization had died on the vine. Only in 2022 was the concept put to the test again in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Assault on Hostomel

The Battle of Antonov Airport is perhaps the only operational-level air assault in history conducted in support of a breakthrough. It is worth briefly reviewing the basic course of events (detailed in a recent article).

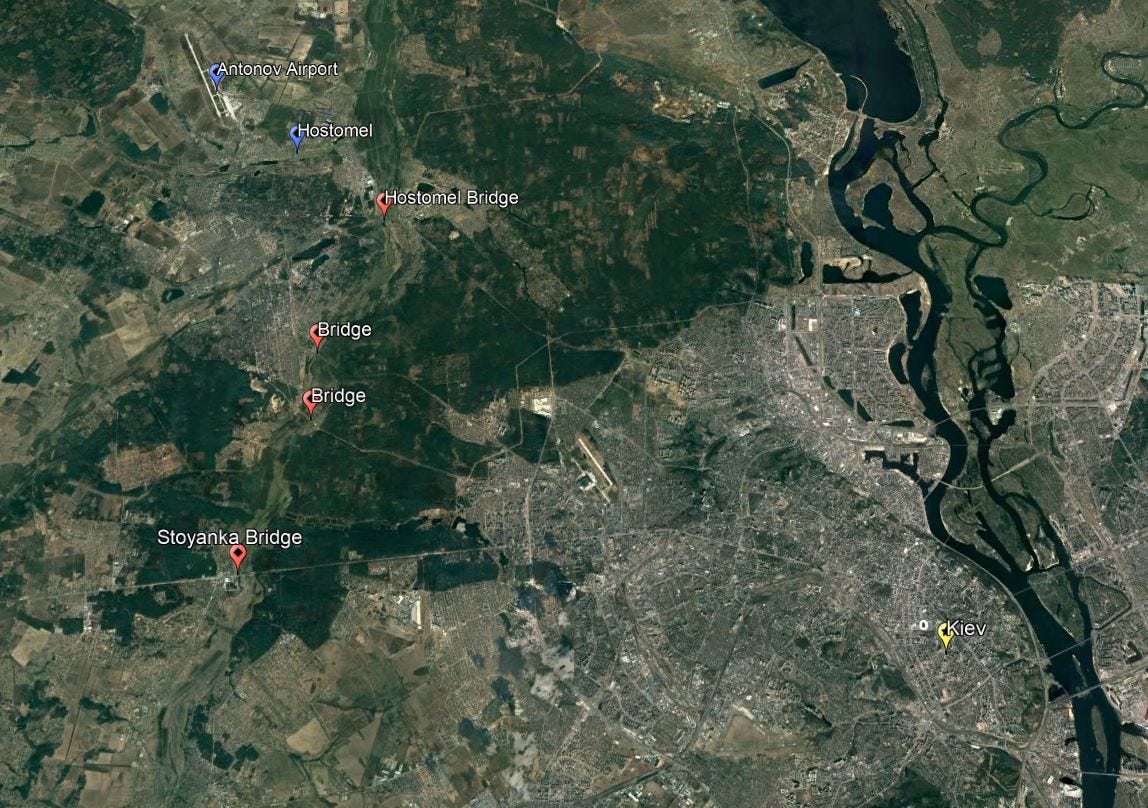

Around 0930 on 24 February, hours after the ground invasion had begun, a flight of helicopters carrying Russian VDV (airborne troops) crossed the Ukrainian border from Belarus. It was preceded by a series of ballistic missile strikes and accompanied by EW jamming which suppressed Ukrainian air defenses, although the Russians lost at least three helicopters to MANPADS and Ukrainian jets. Around 1100, some 300 VDV landed at Antonov Airport in Hostomel. They captured the airport in a two-hour battle in which another four helicopters were downed. The surviving helicopters then returned to Belarus, leaving the VDV with only a pair of jets for air support until reinforcements could arrive.

Ukrainian regular forces moved up to Hostomel that afternoon and counterattacked with mechanized infantry and artillery around 1730. After several hours of fighting, they succeeded in driving off the VDV, who took refuge in a nearby wood. Just around when the counterattack was launched, eighteen Il-76 transport planes were reported inbound from Pskov, the home base of the 76th Guards Air Assault Division. They were due to arrive no later than 1900, but fighting at the airport forced them to return home.

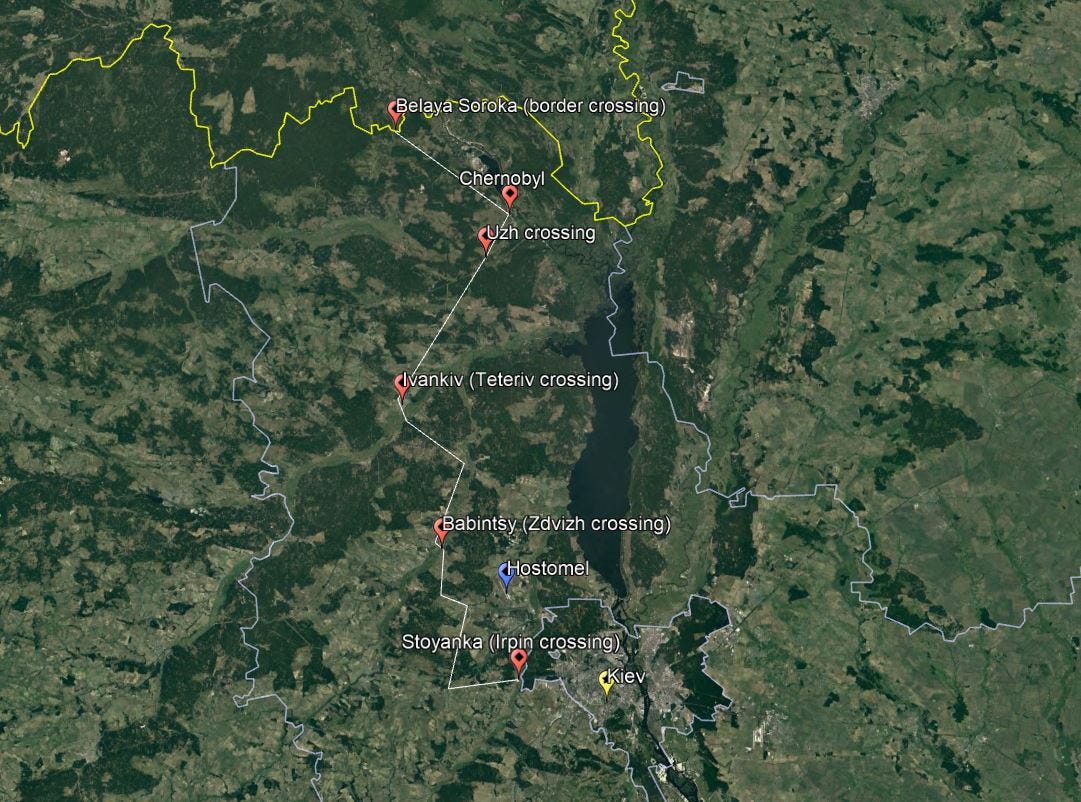

Russian ground forces had meanwhile entered Ukraine from Belarus around 0400 and were drawing near Kiev. They got engaged in heavy fighting around Ivankiv, where Ukrainian airborne managed to blow the bridge, but not before the 5th Separate Guards Tank Brigade broke through to reach Hostomel the following morning. Ukrainian forces at the airport withdrew at their approach, shelling the tarmac to render it unusable. There was intense fighting in Hostomel over the next few weeks as both sides poured in reinforcements, leading to a deadlock until the Russians withdrew entirely at the end of March.

Before we can draw any general conclusions about the prospects of air-mechanized assaults in modern warfare, we have to consider what specifically the Russians were trying to accomplish at Hostomel. Fortunately, captured document gives us a very good idea.

The Scheme of Maneuver

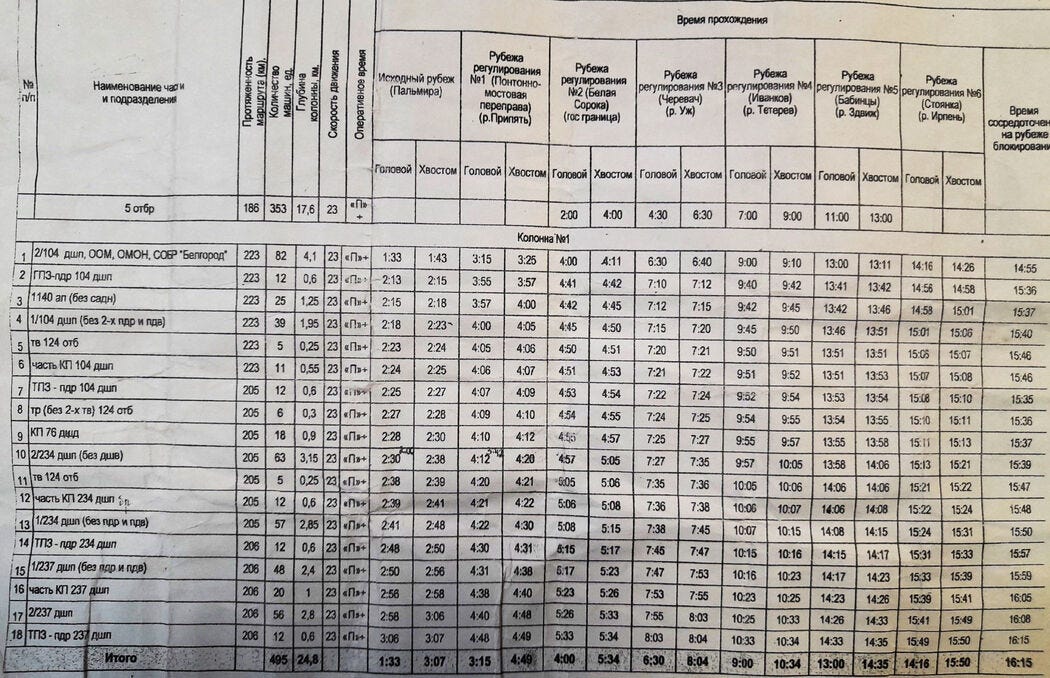

Sometime during the first weeks of the war, Ukrainian forces recovered a timetable for the 5th Separate Guards Tank Brigade and the 76th Guards Air Assault Division, the lead units entering Ukraine from Belarus.

This gives passing times for four checkpoints within Ukraine itself, each of which lay on a bridge over a major water obstacle: the Uzh River south of Chernobyl, the Teteriv at Ivankiv, the Zdvok near Babintsy, and the Irpin at Stoyanka. Only the 76th GAAD is broken down by serial, suggesting the document was intended for its use.

Three things in particular stand out. The first is that no times are listed for the 5th SGTB after the Babintsy checkpoint, suggesting it was supposed to split off from the 76th GAAD at that point. This was the brigade that reached Hostomel on the 25th; judging by the scheduled pace through the previous checkpoints, they were supposed to arrive there between 1200 and 1300 on the 24th.

The timetable shows the brigade crossing the border at 0200, however, whereas Russian troops did not cross until 0400, so it is likely that the entire operation was delayed two hours. This means that the lead elements would have arrived at Hostomel by 1500, well inside the doctrinal six-hour window that ground forces have to link up with the assault element (intriguingly, the Ukrainian counterattack came just after that window closed). Notably, this deadline was before the Il-76s even launched. Although it is entirely possible that the planes were delayed, it implies that the Russians intended to secure the airfield with armor well before air reinforcements arrived.

A second detail tells us the assault forces’ likely objective. After the 5th SGTB and 76th GAAD parted ways, the latter was supposed to head to Stoyanka, the southernmost of four nearby crossings of the Irpin. Once over the bridge, they were to establish blocking positions no later than 1615 (perhaps revised to 1815). The intent was presumably to preempt and block any reserves arriving from the capital, while securing the last major obstacle for follow-on forces—the 5th, the 35th, and the rest of the 36th Combined Arms Armies (of which the 5th SGTB formed the vanguard). The northern forces were therefore almost certainly given a similar task, to seize the bridge near Hostomel and form a blocking position there.

What, then, were the plane-bound reinforcements? A single Il-76 can carry one T-72 or three BMDs, meaning eighteen planes can barely transport a single airborne battalion with all its vehicles; alternatively, it could bring a company of tanks. Assuming the reinforcements were also from the 76th GAAD, a third detail in the timetable tells us what these might have been. The serials reveal that nearly a regiment’s worth of infantry and a self-propelled mortar battalion was detached from 76th GAAD’s various subunits; only a single company from the tank battalion was present, and the anti-air regiment was entirely absent. It is most likely that the first wave would have been mostly infantry, with the possible addition of some air-defenses: the former to balance out the armor- and artillery-heavy 5th SGTB, the latter to secure the airfield for follow-on reinforcements.

Threading the Needle

All told, the assault on Antonov Airport is not a great illustration of a true air-mechanized assault, most plainly because the assault itself did not feature a mechanized component. This is further complicated by the fact that the airport itself was not the operational objective—that was the bridge, which was to be seized by a combination of follow-on airborne and armor.

Nevertheless, the battle indirectly shows both the promise and peril of the air-mechanized concept. On the one hand, it demonstrated how relatively large-scale heliborne insertions are eminently feasible when supported by fixed-wing aviation and EW. The landing and initial actions on the objective were successful, while the subsequent loss of the airport and ultimate failure to capture the bridge over the Irpin owed more to the ground forces’ delay. Even so, the operation was a limited success insofar as it forced the early commitment of reserves that might otherwise have bottled up the advancing Russian column, which did not even cross the Teteriv until the 25th. The operation came at the loss of only seven helicopters—not a terrible price for a high-risk mission with the potential to shape the entire course of the war.

But that’s the rub: no matter how feasible the insertion, the assault itself is never an easy task. Anything operationally valuable is also bound to be defended, reinforcing the importance of the mechanized part of the air-mechanized assault—and hence the need for organic heavy lift. Even for an objective as lightly defended as the Antonov Airport, the VDV would have required BDMs and 2S9s at a minimum to repulse the counterattack. Seizing the bridge over the Irpin would have required considerably more support, judging by the ambush sprung on a wayward Rosgvardia unit that wandered across.

This leaves open the question of whether it is even possible to squeeze an adequate mix of mobility, protection, and firepower through the narrow tube of helicopter lift. Basic mobility is an absolute necessity when long-range fire can be pre-registered on likely landing zones. Armor is very demanding in lift capacity, and can never be sufficient. The solution might lie in firepower, the third corner of the iron triangle.

Long-range precision fires have been one of the defining factors of the Ukraine War, effective both tactically and in depth. Could these systems be even more effective if deployed in the enemy’s depth, where they could strike vulnerable targets and interfere with the movement of reserves? Unlike typical air assaults, which must often go against the enemy’s reserves, the standoff of long-range artillery allows it to be inserted in areas that are far from the enemy’s strength.

There is in fact doctrinal precedent for this, the oft-trained but little-implemented artillery raid. We will look this in more detail in next week’s article.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Airlifting artillery forward also raises the question of sustainment and ammunition - do you have enough airlift and/or can you keep it safe long enough to deliver enough ammunition to make a difference?

The 101st Airborne didn’t conduct any raids in Desert Storm. They sent the the division as a blocking force along with the 82nd ABN (by truck) and a French Division. At the time it was the largest and longest air mobile assault in history. I’m pretty sure that wasn’t considered a tactical move or a raid. Great article otherwise.