Charging the Brick Wall: The Problem of Deployment in the Face of a Modern Defense

Events in Ukraine are showing just how difficult it is to conduct an offensive against prepared defensive lines. Much of this owes to the proliferation of drone-enabled precision-guided weapons: these not only make the break-in battle much more difficult, but render a true operational breakthrough much less likely. What we have not yet seen is how these factors will affect the initial phases of any future war. The impact is likely to be profound.

My last piece looked at how linear fronts develop in the first place. Late Soviet doctrine sought to avoid the formation of frontlines altogether by means of fast-paced meeting engagements: a compromise between tactical deployments and operational tempo to win a decision early in the war. Could this work in any contemporary conflict?

The Russian invasion of Ukraine followed this pattern in the broadest of strokes. Multiple columns made sweeping territorial gains in the opening weeks, pushing through points of Ukrainian resistance until their momentum stalled along lines in the Donbas and south which have only gradually changed in the meantime. Basic tactical unpreparedness prevented them from accomplishing any decisive breakthroughs in the Donbas, leaving open the question of how well a better-organized force might have fared (Kiev was always out of reach once the Ukrainians made the decision to defend it).

But that was in 2022. Even those gains simply would not have been possible against the Ukrainian army of one year later. Questions of mobilization and posture aside, an AFU equipped with more long-range precision fires, integrating drone reconnaissance down to a low level across the entire force, would have been able to severely disrupt the dense Russian columns soon after they crossed the line of departure. Any halfway-serious military observing these lessons will modify its own force structure accordingly, making the initial stages of any war much more difficult for the aggressor.

Problems for the Attacker

Even when the defense is only partially prepared, standoff weapons give the defender an enormous advantage. They allow him to quickly punish any formation that remains road-bound, forcing an attacker to disperse his formations well before they are able to range enemy positions with most of their weapons.

This is not an entirely new problem: it is what air interdiction has always tried to do. Manned aviation is a scarce asset, however, one which cannot be replenished on the timescale of a short war. This imposed a serious dilemma on NATO planners of the Cold War: whether to allocate more resources toward disrupting an offensive in the early stages or focusing more on CAS and interdiction once ground forces were engaged (the Soviets, for their part, invested in mobile air defense that could provide sufficient protection until their columns could reach the enemy line).

Disposable missiles and drones do not face this limitation. Even the best missile defenses can be overwhelmed, leaving them susceptible to saturation waves early on. It is also not so easy for the attacker to integrate these countermeasures. The most effective antimissile weapons have proven to be NASAMS and IRIS-T, which have firing ranges of 25-50 km depending on the variant. This is much shorter than the range of ballistic missiles and drones, forcing the attacker to deploy these systems when the enemy is still far outside of range of most ground fires. Pairs of systems can provide leapfrogging coverage, but this either requires a slow advance or effectively halves the number of an already-scarce asset. Their range is also not much greater than most tube artillery, leaving them vulnerable to ground counterattack unless sufficient assets are deployed to protect it, which would only further stretch out timelines.

Nor can the attacker rely on surprise. Persistent surveillance makes it impossible to conceal a build-up of any size, meaning that true strategic surprise is even more difficult to accomplish than an operational breakthrough; at best, one can conceal the timing and broad thrust of an offensive.

The Last 100 Kilometers

This raises the question: how does an attacker even deploy in the face of such a defense? Never mind the problem of breaking through the enemy’s defense, how do they get to it? Let’s consider the case where two near-peers are equipped with the best of what both Russia and Ukraine currently have. The defender has prepared positions along the main axes of advance, 20-100 km forward of the defender’s main reserves, enough to impede but not stop the progress of a heavy column.

There are broadly two plausible approaches for the attacker. The first is to deploy early and far out, then proceed under the protection of nested defensive and offensive fires. Ground combat units advance in phases along secondary and tertiary routes, moving cross-country where they must and setting up fighting positions and supply points at each step. Dispersion laterally and in depth mitigates the missile threat, although forces must still concentrate against any fortified positions they encounter. This approach is slow, predictable, and risks allowing the enemy to establish a line of contact far back from any strategic objectives.

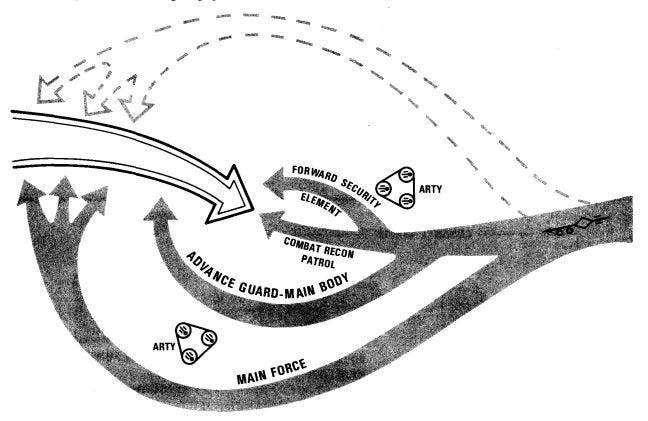

The alternative superficially resembles a classic heavy break-in. Parallel columns advance in multiple echelons, maintaining enough momentum to reach their objective before stalling out. But their objective is not to open a gap in the enemy’s defenses, it is merely to deploy against them; succeeding echelons do not try to push deeper into the defensive zone, but fall in on the line established by the first.

Maintaining momentum would be the hardest part. As with a traditional break-in battle, it hinges on simultaneity of efforts: strikes across the enemy’s depth by air, ballistic missiles, and special forces; engineering teams clearing obstacles in advance of the main columns; nested protective capabilities, to include long-range air and missile defense, point defense, EW, and counterbattery fire. These efforts must be preplanned and sustained with intensity so long as the columns are advancing.

No matter how intense the initial onslaught, the attacker will inevitably incur heavy losses on the approach. This means that first echelon forces especially must be prepared to operate at greatly reduced capacity, devolving decision-making and resources to a very low level. Their primary objective is to form a screen behind which follow-on forces can deploy.

Forming the Line

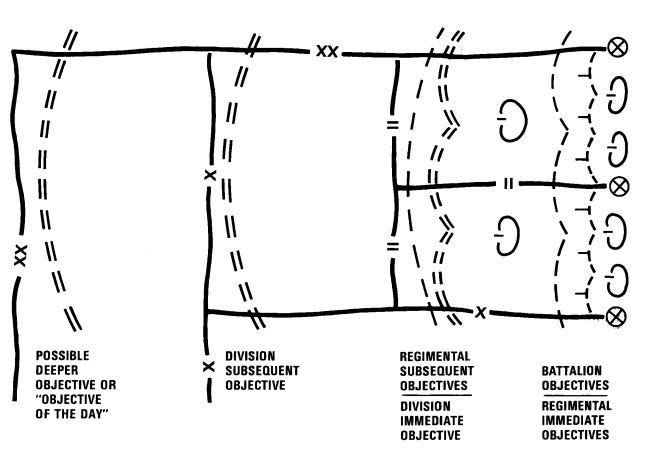

There is nothing preordained about where the front eventually settles. The line of contact usually starts to form around points where the defense commits its reserves, as both sides deploy laterally to outflank each other (much like a classic pre-mechanized deployment). This poses a dilemma for the attacker: whether to commit subsequent echelons to break through points of resistance or to dig in once moderate resistance is encountered.

This is not an easy decision to make. It is always tempting to push forward as far as possible, but the value of a narrow tactical breakthrough must be balanced against the cost in manpower, ammunition, and time, the position of adjacent units, and the demands of follow-on actions. The operating assumption is that the attacker will run out of steam before accomplishing anything of true strategic value, so the priority is setting conditions for the next phase (which, I argue in another piece, is likely to be a series of heaves that keeps the enemy off balance).

This makes the initial advance something between a reconnaissance-in-force and a struggle for position. Follow-on echelons can be redirected to potentially vulnerable sectors based on BDAs, ongoing surveillance of the rear areas, standing intelligence estimates, and where the line of contact actually settles. Once the commander has an idea of this, he can start transitioning to the build-up of pressure for the next phase.

Wars of the Future

This is only an idea of how the early stages of a future ground campaign might progress under certain operational assumptions. It is impossible to say how new technology might upend these assumptions; nor is it to say that a future aggressor would even choose such a course—it is bound to be expensive in men and materiel, and require an enormous stock of PGMs to stand any chance of success. Belligerents may instead choose to pursue more of an air or naval strategy, or limit themselves to lower-intensity border fighting.

Nevertheless, it is worth considering this problem in detail. Potential aggressors and defenders alike must be prepared to face it, however remote the odds. These considerations are also likely to shape the course of weapons development as militaries seek to expand their options. Whether directly or indirectly, they will likely impact the future course of warfare.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

War is politics by other means, so I expect we'll see a lot more politicking, economicking, revolutioning, and soft power-ing in the future. This stuff just seems too costly unless you can stoke an existing fire in the form of existing dissatisfaction with the regime you don't like.

Of course, when the worst comes, you still have to be ready to push your little army pieces to the center of the table and say "all in".

Excellent piece. Very informative and thought out