Contested Crossings: Fighting Across Rivers in the Gunpowder Age

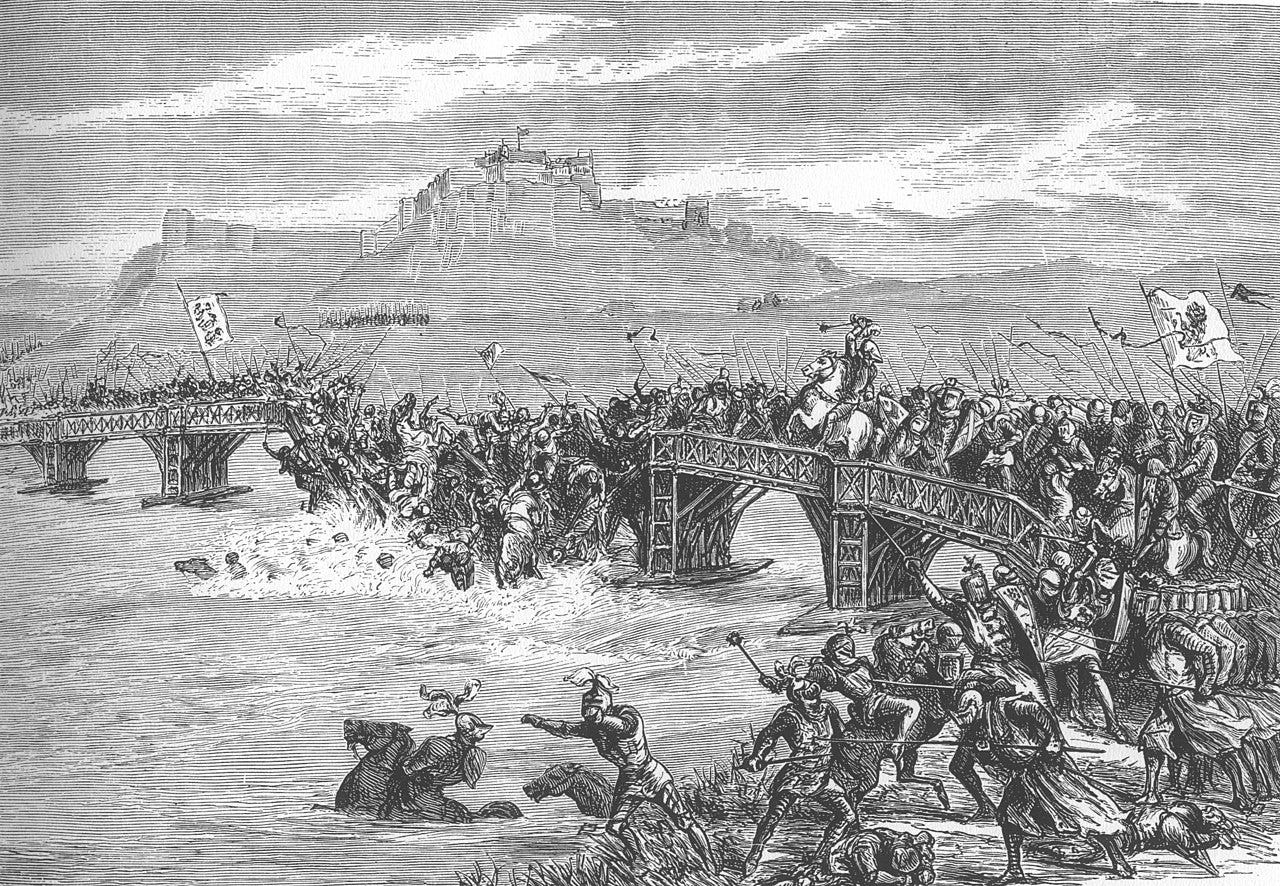

In 1297, Edward I of England sent an army into Scotland under the Earl of Surrey to put down William Wallace’s rebellion. After arriving at Stirling Castle, Surrey found the Scots drawn up on the opposite side of the River Forth. Wallace had positioned his men some ways back from the river itself, so Surrey decided to advance, anticipating that he would have time to form up his army before becoming engaged.

This proved to be a mistake. It was a slow passage, as the narrow bridge only allowed a few across at a time. When maybe half the English had crossed, the Scots charged. The weight of their infantry thrust the vanguard back against the river. Many Englishmen scrambled to get back over the bridge, but the narrow passage only funneled them into a compact mass, making them easy prey for the howling Scots. The slaughter was horrific, amounting to over half of Surrey’s army, which thereafter retreated to Stirling Castle.

The Battle of Stirling Bridge illustrates the perennial danger of crossing a river in the face of the enemy. As history continues to demonstrate up to the present fighting in Ukraine, opposed river crossings are one of the most difficult tasks that can be asked of a ground commander. The risk of being attacked while out of formation, with only partial strength, and possibly cut off on a hostile shore is simply too great to undertake without careful preparation.

It is for precisely this reason that battles such as Stirling Bridge were rare. Attacking generals preferred to find some poorly defended crossing to slip across, securing a bridgehead before the enemy could respond. Flipping the board around to the defender’s point of view, guarding the line of a river is not too unlike defending a mountain range: what is easy at the tactical level is not necessarily so at the operational level. Without comfortable numerical superiority on the defender’s part, an opponent was always liable to steal a march, leaving the defender in a far worse position than before.

The gunpowder era changed these calculations. Sometimes this was to the defender’s benefit: a well-entrenched and well-armed position could render a crossing even more difficult. On the other hand, an army with firepower dominance could create room on the far bank for the vanguard to cross and form up. And when the attacker’s advantage was less than overwhelming, he could still credibly threaten to force a crossing in order to fix the enemy before crossing elsewhere—or feign a downstream maneuver to draw off strength from the main defensive position.

In short, gunpowder opened up creative possibilities for what has always been a tough tactical problem. Solutions varied according to force composition, terrain, and the broader strategic and operational context, as several case studies from the 16th to 19th century illustrate.

The Garigliano

The full range of possibilities was demonstrated by a major battle at the very dawn of the age of field artillery. The Battle of the Garigliano was the second of two major Spanish victories in 1503 which left them in control of southern Italy and lay the groundwork for the vicious fighting of the next 25 years of the Italian Wars. It is best known for Gonzalo de Córdoba’s great flanking maneuver, crossing the river upstream to take the French army in the flank—a typical medieval solution. The full story of the battle is much more complex, however, highlighting the new dynamics struggling to emerge.

In 1503, Louis XII of France sent an army to reconquer the Kingdom of Naples, which had recently been lost to the Spanish after a failed attempt to partition it with them. As his army marched down the Italian peninsula, additional forces arrived by sea at Gaeta, one of the last French possessions in the Kingdom, where the remnants of French forces in Naples had taken refuge. They turned the port into a base of operations, stockpiling supplies there and repairing its fortifications.

These measures soon paid off when Spanish army came up from Naples to besiege Gaeta. Its commander was Gonzalo de Córdoba, Spain’s foremost general. He had already won a great reputation for completing the Reconquista with his capture Granada, and in subsequent wars in Italy innovated new combined arms which he used to win a stunning victory over the French earlier that year at Cerignola. Gonzalo’s genius could not overcome the strong walls and plentiful artillery of Gaeta, however, and he was soon forced to draw off as the main French army approached in late September.

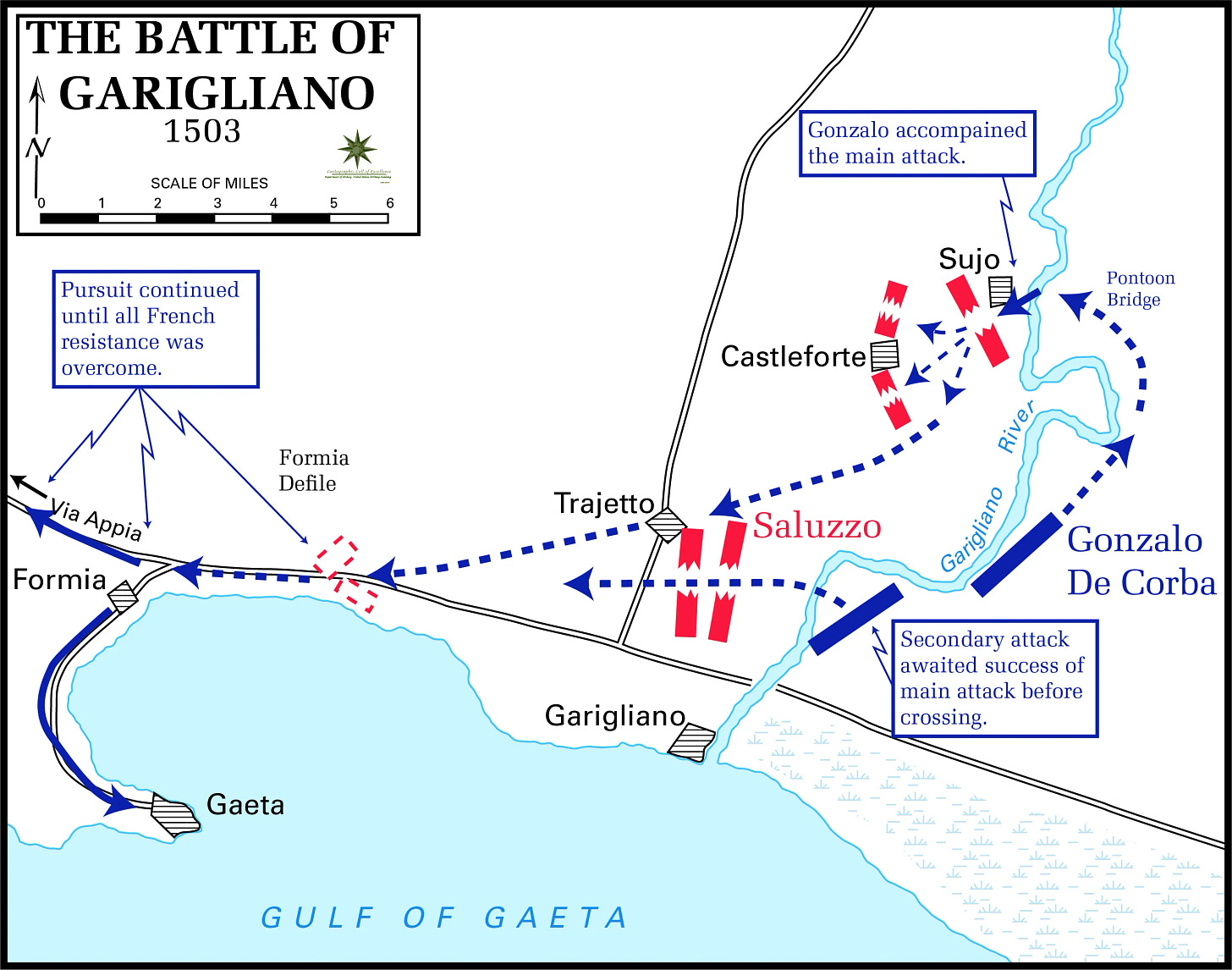

After some maneuvering, the invading column joined with the forces at Gaeta and Gonzalo retreated over the River Garigliano, 20 km down the coast. There were no bridges standing on the lower course of the river and the Spanish retained several fortified places near the crossings upstream, so the French were left to construct a pontoon bridge. They were much stronger than their adversary by this point and held an overwhelming advantage in artillery—they had brought a large train for the anticipated siege of Naples plus many smaller field pieces.

After several cross-river raids failed to dislodge the Spanish from their fortified camp, the French lined their side of the river with cannon and mounted guns on barges, forcing Gonzalo to pull back about a mile. This gave French engineers room to assemble a makeshift bridge. A vanguard of some 4000 infantry crossed the river in early November and constructed a bastion to protect the bridgehead.

Notwithstanding this protected foothold, the French could not immediately attack. It would take many hours to pass the entire army over the Garigliano and form up in a battle line, leaving them vulnerable to a Stirling-style attack—although their artillery could prevent the Spanish from lingering, the slow-firing and inaccurate guns of the 16th century could not save an isolated force in disarray. As if to prove the point, Gonzalo attacked the vanguard with his entire strength just days later. He inflicted substantial casualties on the enemy, but endured even worse between the cannon fire and fighting on the earthworks. He was eventually forced back, and the French continued work on another two bridges to speed their eventual crossing.

Gonzalo now felt the walls closing in. He had failed to pinch off the enemy’s bridgehead, making it almost inevitable that the French would be able to pass their entire army over the river. The weather was terrible, and many of his men lay sick or dying. Yet things were imperceptibly shifting in his favor. French strength was also evaporating to sickness and desertion. The rains slowed work on the bridges, and flooded countryside on the southern shore rendered an advance impossible. Prolonged misery exacerbated frictions among the French, Swiss, and Italian soldiers who composed the enemy army. As the weeks wore on, many abandoned the miserable camp altogether, reducing French numbers greatly from an original strength of over 22,000.

Gonzalo was meanwhile gaining strength. The Spanish ambassador in Rome contracted a large contingent of Italian mercenaries under the condottiere Bartolomeo d’Alviano, who arrived at the Spanish camp in December. This gave Gonzalo more infantry than his enemy, even if he remained weaker in cavalry, lending him the confidence to go on the offensive. Leaving a body of troops to mask the bridgehead, he constructed a bridge of his own about 8 km upstream and crossed on the 28th, rapidly sweeping aside their pickets and securing a lodgment. The next morning, he struck in force.

The French camp was spread out over an area more than 15 km wide, rendering organized resistance impossible. As panic turned to flight, the corps covering the bridgehead pressed over and attacked the enemy from another direction. The rout was total: only a rearguard action by the French cavalry saved the army from complete destruction. Most of the fugitives found shelter in the walls of Gaeta, but this fell to a siege several days later.

Every battle is unique both in its particulars and in the broader operational and strategic context, and the Battle of the Garigliano proves no general rule—there were many factors that accounted for the success of Spanish maneuver and failure of French firepower. The battle nevertheless revealed the potential for a well-equipped army to force a crossing even in the face of a strong opponent; with more vigorous and competent leadership, there is no reason to believe a similar army could not have been successful.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.