Deployment: The Supremacy of the Battleline

For as long as humans have engaged in organized warfare, we have been fighting in lines. No matter the weapons, armor, or mix of forces involved, a battleline solves two major problems at once: it maximizes the fighting power in contact with the enemy, and it protects individual elements from being flanked and isolated. This is just as true for a hoplite army equipped with spear and aspis as for modern infantry with interlocking fields of fire.

The battleline is so important that deploying a force for combat is arguably the most fundamental problem of tactics (in this sense, the word remains essentially true to its etymological origin). The side that is able to draw itself up faster and in better order enters battle with a huge advantage over its enemy.

The Mechanics

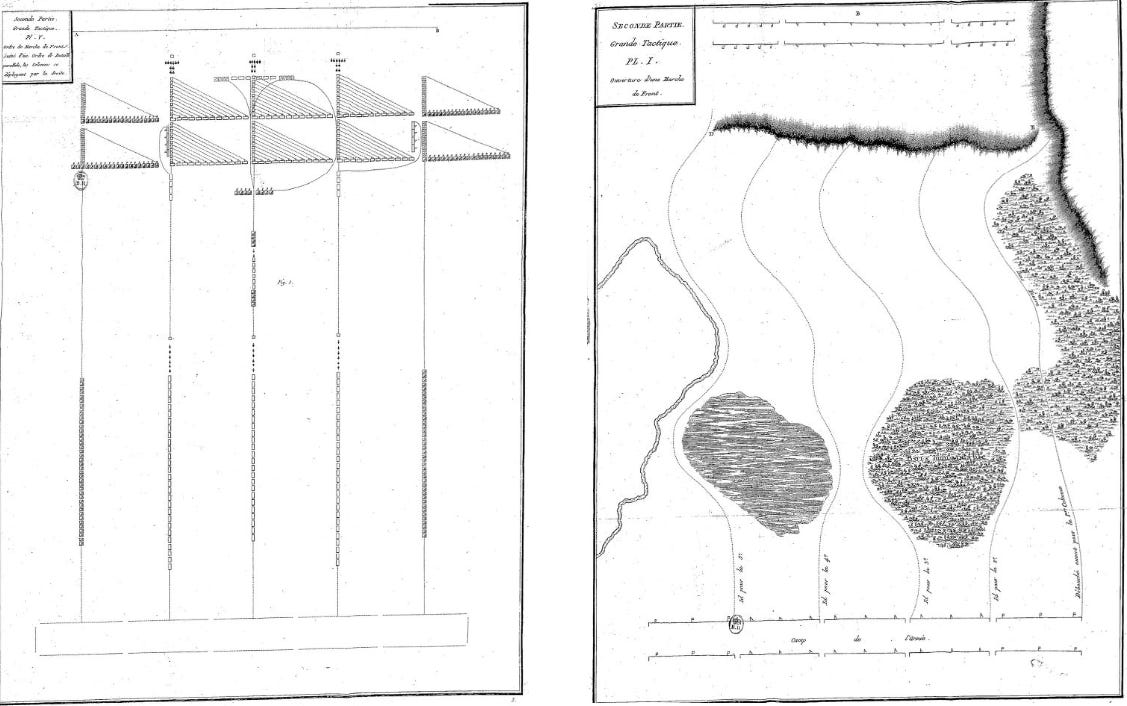

This is a far harder problem that it first appears. Among the ancient Greeks, only the Spartans were able to deploy quickly. They marched in a column of platoon-sized elements, which deployed by passing a certain distance to the left or right then advancing on line. This eventually became the standard for all sophisticated armies of the ancient world.

Past a certain size, the marching column would have extended several miles, making it impractical to deploy from a single column. Roman legionary armies mitigated this by marching in several parallel columns on the immediate approach, something also done by European armies in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Much planning went into their composition, spacing, and march-order: the advance guard for each had to have sufficient artillery to deal with any detachments along the way, but not so much as to impede the main body.

If a commander in any of these periods felt that he could not properly deploy his army, whether for reasons of topography or the presence of enemy detachments, he would simply avoid battle. Not being able to form up in good order meant not being able to fight; he could instead remain in a fortified position or withdraw from the area altogether. This explains the imagined formality of eighteenth-century warfare and the chivalric challenges to battle in the Middle Ages: the only way to reach a decision was often to give the enemy a fair chance to line up (when generals could surprise an army on the march or in camp, they of course did).

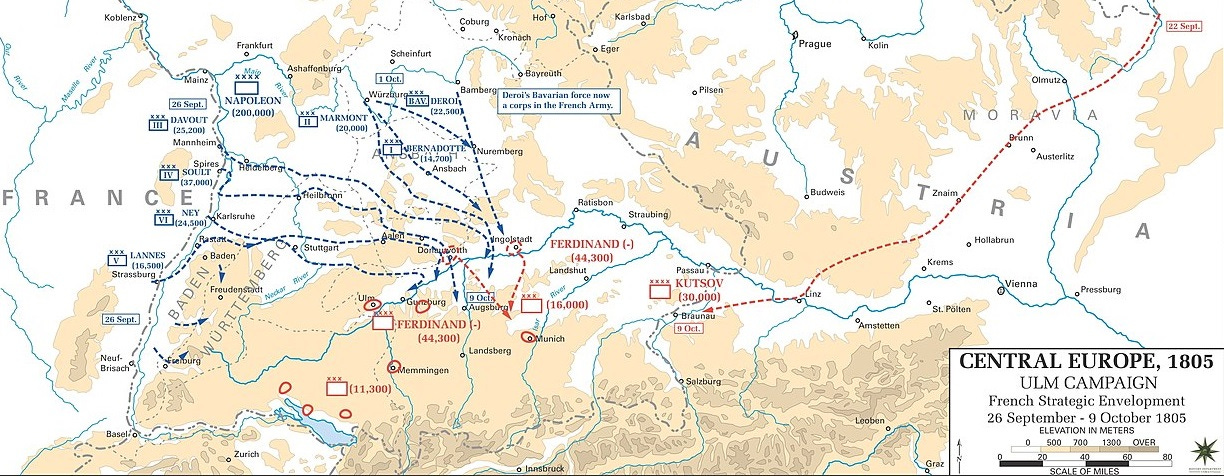

As armies grew in size over the course of the nineteenth century, avoiding combat was not so simple. Forces moved along multiple routes even when distant from the enemy, over a front dozens if not hundreds of miles wide. This left individual columns little freedom to maneuver; they had to be prepared to deploy and fight whether or not a general engagement was sought—the corps d’armée system was designed with this in mind.

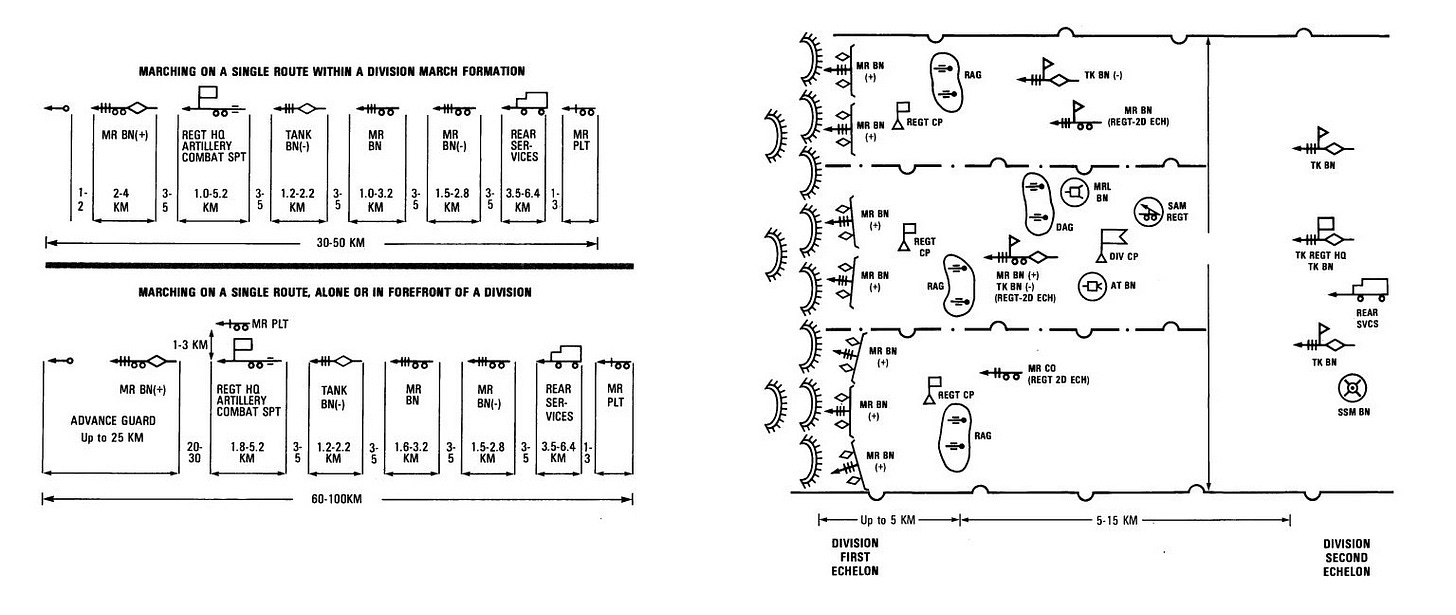

Going into the modern era, the mechanics of deployment remained fundamentally the same, if more complex. The lead element of a formation required sufficient artillery support to get on line and engage the enemy while the rest of the column came up; all subordinate units had to order their armor, artillery, and engineers appropriately.

Tempo

Deployment only became a fundamentally different problem in the twentieth century, when opposing forces grew to occupy a continuous front. This posed a dilemma between tactical necessity and operational tempo. Once the enemy was given a chance to set his lines, it became much harder to push through—Germany’s inability to maintain momentum in 1914 nullified her numerous tactical victories. Although generals eventually solved the problem of breaking through fortified lines, this was enormously expensive in equipment and lives, and usually only succeeded pushing the front back to another set of defensive lines.

Soviet doctrine formally divided war into two phases: the initial mobile phase, characterized by disjointed meeting engagements, and a longer phase fought along a continuous front. The first phase was the most dangerous, as it could result in defeat before most forces could even be brought to the front—as happened in May 1940 and nearly again a year later. On the other hand, this phase brought great opportunity to win a war outright in a matter of weeks.

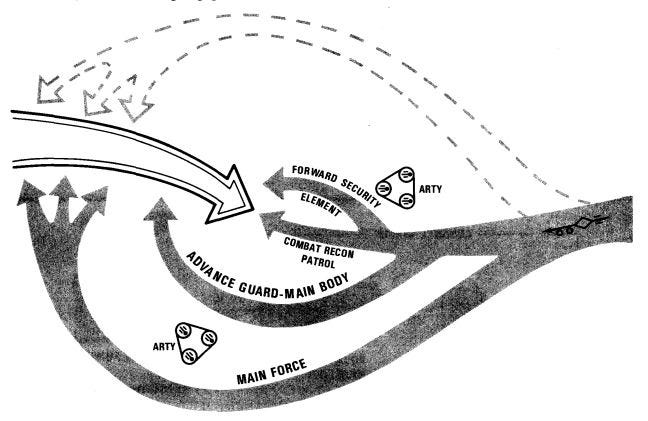

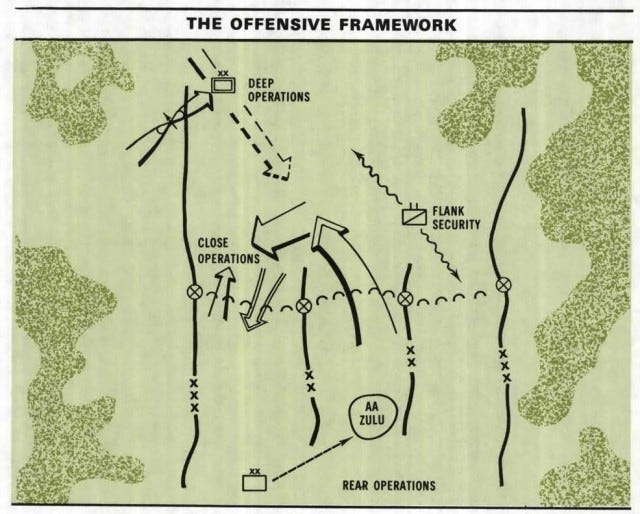

Planners accordingly spent enormous energy figuring out how to keep up the momentum of the offense. They tried to reconcile tactical deployment and operational tempo by developing a doctrine of fighting on the move. Column densities were very high, with no more than 50-meter intervals between vehicles. Air defenses were expected to operate on the march. As soon as the advance guard made contact with the enemy, the main body would look to bypass and flank him. This type of maneuver was to be carried out by units of every size, from company to army group, so that forward movement would not cease.

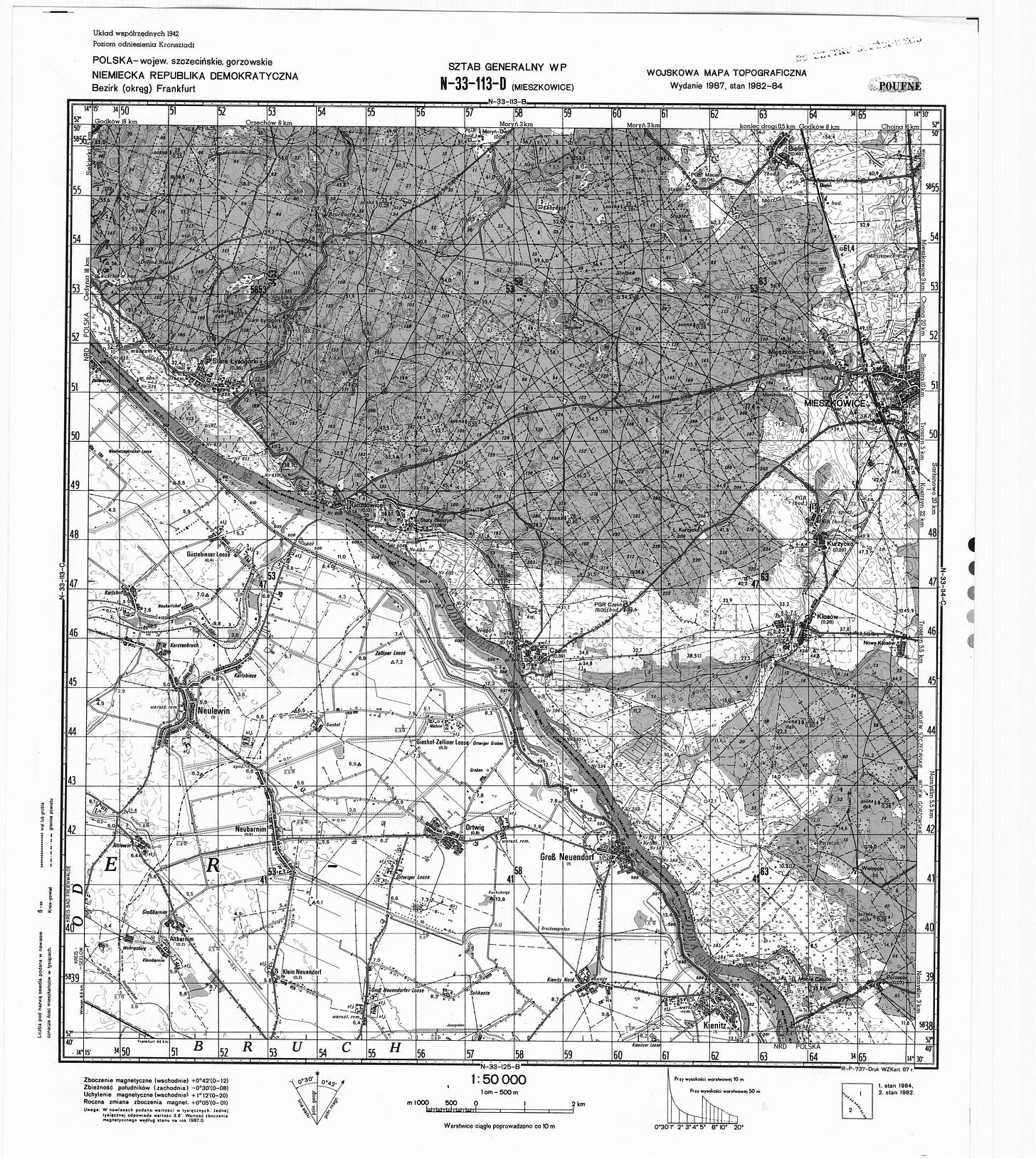

Although this phase was chaotic and uncertain, it required careful intelligence preparation. Secondary and alternate routes had to be mapped out in advance so that follow-on forces could divert on a moment’s notice (as well as to maintain high troop densities along the front). Bridges and river fords had to be noted, including their width, surface material, and load capacity. To accomplish this, Soviet agents produced incredibly detailed maps, both of Warsaw Pact and NATO countries.1

Modern Problems

The Soviet compromise between tactical deployment and operational tempo was never properly tested. Many Western analysts speculated that top-down Soviet command-and-control would kill the initiative needed at lower levels to keep things moving. Beyond that, such dense columns would inevitably create dreadful traffic jams as they passed through the urbanized terrain of Western Europe. Ukraine might have provided a test case in more favorable terrain but for Russia’s more elementary tactical failures. Momentum was dissipated by an inability to effectively coordinate fires and bring maneuver units up on line.

As I write this, mechanized companies and battalions of the Ukrainian counteroffensive are struggling to pass through breach lanes so that they can form up against Russian defensive lines. This demonstrates how at a low tactical level, rapid and well-executed deployments will always be important. For larger formations, however, it remains an open question whether they can still achieve results by themselves, or if deployment is merely the prelude to an inevitable grind.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

NATO never developed any comparable doctrine. AirLand Battle, as a largely defensive doctrine, did not rely on such strict timetables, nor could it count on having nearly as many troops immediately available. Instead, it relied on mobile force to flank the first enemy echelon, supported by air power to interdict subsequent echelons.

Thank you for a such a thorough overview.