Domesticated Breeds: The Difficulties of Jointness

Nothing embodies the glamour of warfare—and the exasperation of generals—better than the cavalryman of old. Many a well-timed cavalry charge, carried out by dashing troopers with a splendid indifference to death, has snatched glorious victory from desperate straits; by the same token, many of the best-laid plans have been upended by reckless and headlong pursuits that went too far. The two sides of the gallant cavalryman were inseparable; it was the job of every commanding general to exploit the one while mitigating the other.

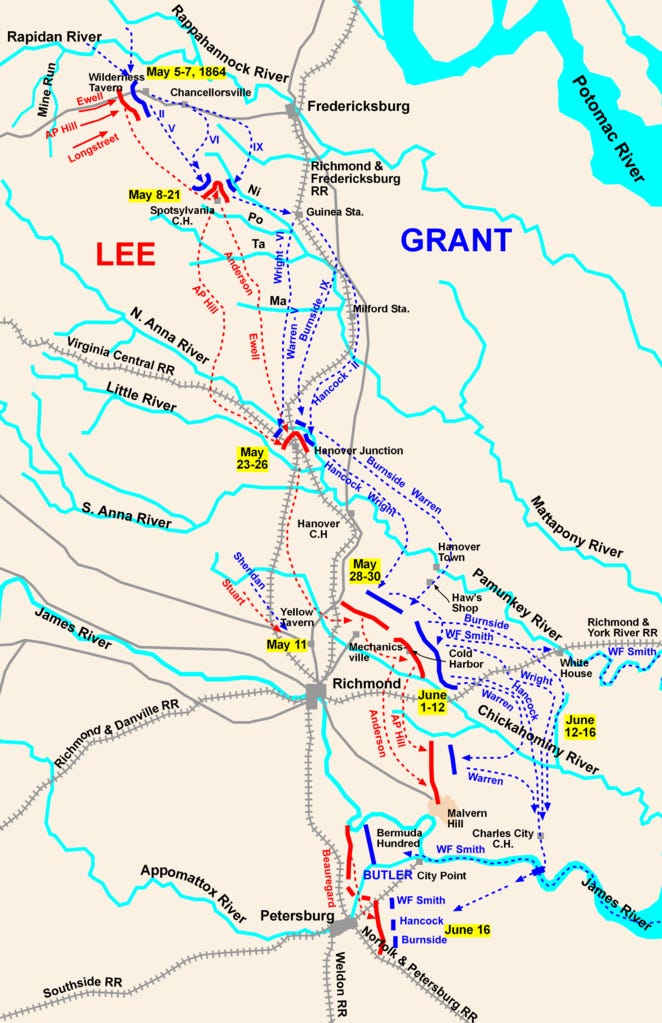

The same held true at higher levels of war. J.E.B. Stuart served as Robert E. Lee’s eyes and ears, giving him critical intelligence for his bold maneuvers; yet Stuart’s daring ride around the Union army during the Pennsylvania campaign famously left Lee blind on the eve of Gettysburg. So too on the Union side: Sheridan’s insistence on chasing after Stuart during the Overland Campaign, instead of scouting and screening for the main army, deprived Meade of a superb opportunity to get around the Confederate flank—forestalling Lee’s defeat an entire year.

Modern Cavalry

The cavalier spirit made a remarkably seamless transition to the tank. Rommel and Guderian embodied it better than anyone: their dashing thrusts across northern France in defiance of orders turned what would have otherwise been an impressive victory into a total triumph. There has been much post-hoc analysis that tried to turn this into some kind of “Blitzkrieg doctrine”, but that is to imagine an intellectual edifice in the place of instinctive disposition, as if a Border Collie has a grand plan when it herds sheep.

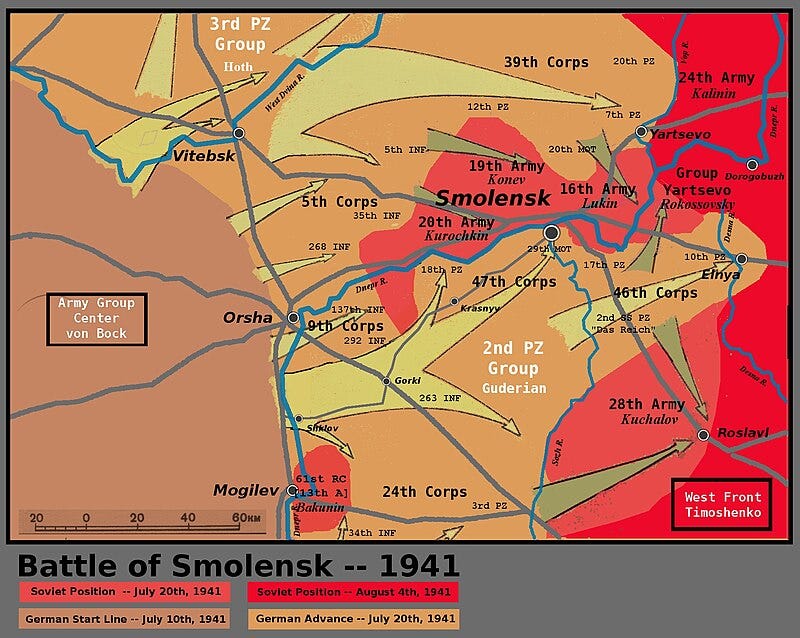

This was more obvious on the Eastern Front, where the cavalier instinct often led directly to disaster. Guderian, as one of two Panzer corps commanders in Army Group Center, undermined Bock’s planned double envelopment of three Soviet armies at Smolensk. Unlike Hermann Hoth, the more reliable commander of 2nd Panzer Group who faithfully played his role as the left pincer, Guderian diverted forces to secure bridges for the drive on Moscow before completing the encirclement; this made the eventual German victory much costlier and allowed many Soviet troops to escape.

Rommel, too, kept pushing on and on across North Africa, stretching his lines of the support to the breaking point instead of pulling back to consolidate. He was not completely blind to higher strategy—he acknowledged the importance of taking Malta in order to hold the Axis position in Africa—but whenever faced with a choice between the two, he always broke in favor of chasing one more victory instead of consolidating.

Interarm and Interservice Cooperation

Clash of opposing temperaments have always been an inherent part of combined-arms warfare. If cavalrymen are far more aggressive than the infantry, infantry commanders are similarly maddened by the artillery’s comparative caution. So too with joint warfare: in amphibious operations, squadron commanders’ concern for their expensive and fragile vessels makes them anxious about the weather, tides, and enemy—too anxious, in many a ground commander’s eyes.

That is not to say that the only difference between arms and components is in tolerance for risk. A cavalryman favors a fast and aggressive approach because cavalry is particularly suited to such attacks; what an infantry or artillery commander favors in a given situation depends on how they can best be employed. Everyone wants a chance to use the weapon in his hands; no one wants to be stuck guarding an unimportant flank during the main attack.

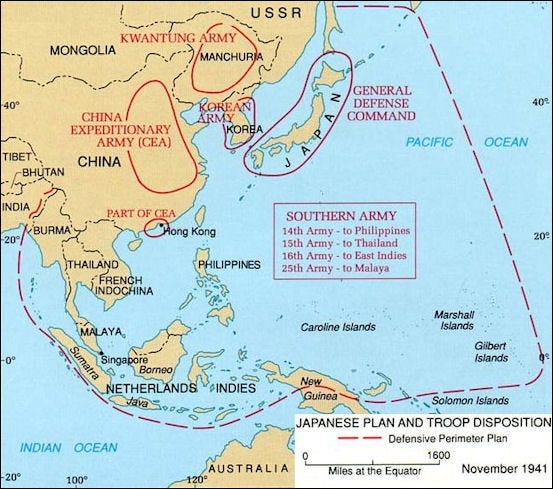

At its worst, this tension can lead to completely divergent objectives, like the Imperial Japanese Army and Navy in World War II. Instead of pursuing mutually-supporting operations, the Army threw its efforts into China while the Navy fought a separate war in the Pacific. The task of a joint or combined-arms commander is therefore to corral his subordinates’ natural dispositions toward a larger objective.

In the United States, these difficulties prompted examination of the institutional barriers to joint cooperation. The 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act took operational authority away from service chiefs, giving it instead to designated joint theater commanders who reported directly to the Secretary of Defense. The intent was to make them less likely to fall prone to their own service’s particular biases and avoid the breakdown in interservice cooperation that had bedeviled joint task forces in the past. The Gulf War in 1991 was the first real test of this concept, and its stunning success validated by every measure.

What is more interesting is how it won that victory. A successful joint campaign is not a compromise among the various components; far more often, one of the available choices is the correct one. During the planning for Desert Storm, the different services advocated radically different courses of action, like hounds pulling their owner in three separate directions. The Army envisioned a large-scale ground invasion of Kuwait. The Air Force suggested a prolonged bombardment. Some in the Navy and Marine Corps even favored an amphibious landing.

The Air Force’s plan was the correct one, and by no small margin: the six-week air campaign eviscerated the Iraqi army and spared the coalition many casualties. To be sure, the other services had some influence on the final plan— an amphibious demonstration tied down several Iraqi divisions and a ground invasion delivered the coup de grâce—but these were mere adjuncts to what was fundamentally an Air Force plan.

The concept of operations was only the starting point, however; a study of the detailed planning and execution that followed gives us a more fraternal impression of interservice relations. This was only possible because the separate components already had a high degree of interoperability, which included the beginnings of a joint doctrine. Command over Air Force, Navy, and Marine aviation was exercised by a Joint Force Air Component Command, separate from their individual service hierarchies.

The degree of jointness has only increased in the decades since. Joint doctrine has been further articulated, while systems acquisition has placed a heavy emphasis on interoperability. Serving in joint billets is now an important part of officers’ career progression, and, following the example of Desert Storm, operational command of all combat forces is exercised by domain-specific commands—air, ground, and maritime (and eventually, perhaps, cyber).

Hybrid Torpor

It is tempting to view this as an inevitable progression toward the seamless integration of military capabilities. The increasing jointness and interarm cooperation at lower and lower levels, combined with the natural centralization of control that technology enables, gives the joint commander ever more influence over the tools he wields. Doctrine and concepts could be developed entirely jointly, while individual arms and services are relegated to the role of mere force providers.

Even if that were possible, it would hardly be desirable. Desert Storm was successful precisely because the Air Force vigorously advocated for its own distinct style of fighting at the expense of other services’ preferences. If it were treated as a mere force provider, it would lose the driving ethos which guides their training and tactical development. Breeding a herding dog with a hunting dog produces offspring that can neither herd nor hunt; it is likewise impossible to have good cavalry without the cavalier’s spirit.

If this leads to occasionally imperfect alignment between a commander and his various subordinate arms, services, and components, it is also a source of creative tension—“better a subordinate who has to be reined in than prodded forward.” There is no straightforward organizational solution to managing this tension; only human judgment can find the balance between giving his forces reckless independence and stifling their initiative.

Yet there is another subtler and longer-term balance that must be maintained: that between components. When a command comes to rely too much on one, the others begin to wither—this has arguably been the case with American air power since 1991, just as it was with French artillery after 1918 or heavy cavalry in the Middle Ages. The next piece will look at the longer-term balance among components.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Please like and share if you enjoyed, it helps more people find this. You can also support with a paid subscription, supporters receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529 and get access to exclusive pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.