Lines and Reserves, Part 2: The Pike-and-Shot Era

This is the second of a multi-part series. You can read the first installment here.

The system of deploying armies in multiple lines, used throughout antiquity, became less common in the Middle Ages. The smaller armies of this period typically fought in a single line, backed by a small reserve which could plug a gap or exploit success as needed, although medieval generals occasionally echeloned their line in depth when attacking a narrow front.

The advent of pike-and-shot tactics in 16th-century Europe completely upended these traditional arrangements. The Swiss had proven the worth of deep infantry formations in the 15th century, when their well-drilled pikemen won several unexpected victories over stronger opponents. The proliferation of handheld gunpowder weapons that same century led to experimentation with combined arms within infantry formations, and the Spanish soon figured out how to combine the offensive power of massed gunfire with the staying power of massed pikemen. This evolved by the mid-16th century into the tercio, initially some 3000 strong: a large pike square with four “sleeves”, or small blocks, of arquebusiers that could be positioned as needed, while the pike square itself often had a few outer ranks of arquebusiers.

These deep formations could not be deployed in multiple lines of battle, as had been the case in earlier ages. Western European armies around the year 1500 were still small—even the greatest monarchs were only rarely able to concentrate much more than 10,000 men at a time, amounting to just three or four such blocks. They usually deployed either in a single line, relying on the depth of their formations to give them resilience, or in a diamond.

Over the course of the 16th century, two long-term trends changed this pattern. The first was the expansion of European credit markets, which allowed sovereigns to raise much larger armies. The second was the steady improvement in quantity and quality of artillery, which made it dangerous to concentrate so many troops in large inviting targets. Instead, they were organized into smaller battalions—typically less than two thousand strong—arranged in a checkerboard formation two or three lines deep.

These did not necessarily function like the Roman triplex acies, wherein each line served as a tactical formation unto itself, advancing or withdrawing as a whole. Rather, it allowed battalions to provide mutual support. Rear-line battalions could fire through the gaps and advance to support neighbors to their front, and individual units could be shifted around the battlefield as needed. Friendly cavalry could meanwhile pass freely through the infantry array, but any enemy units that got through would be met with fire from all directions.

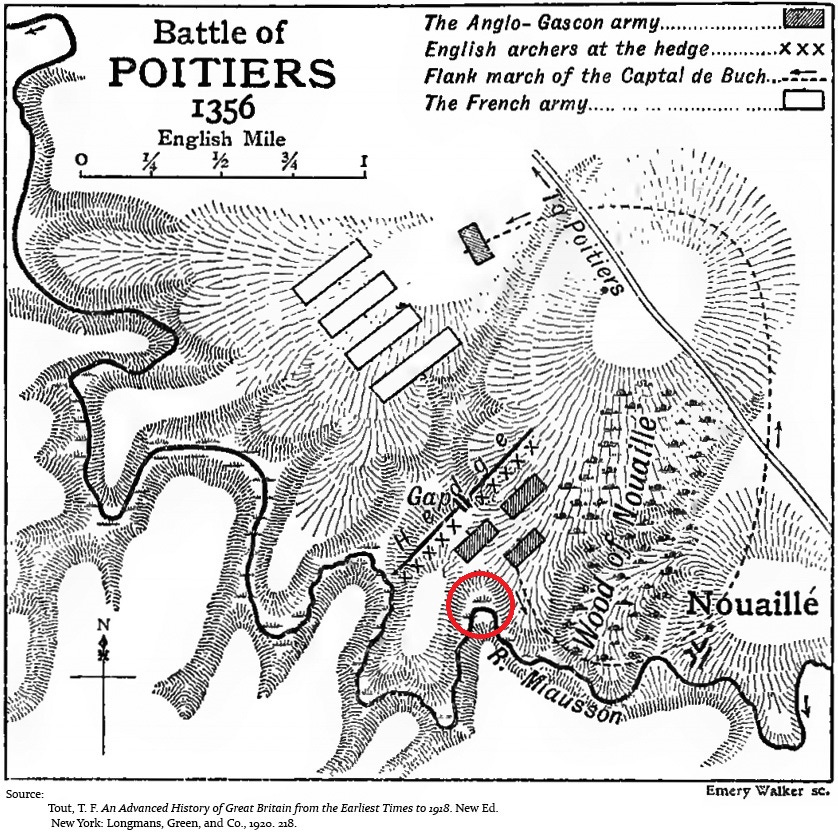

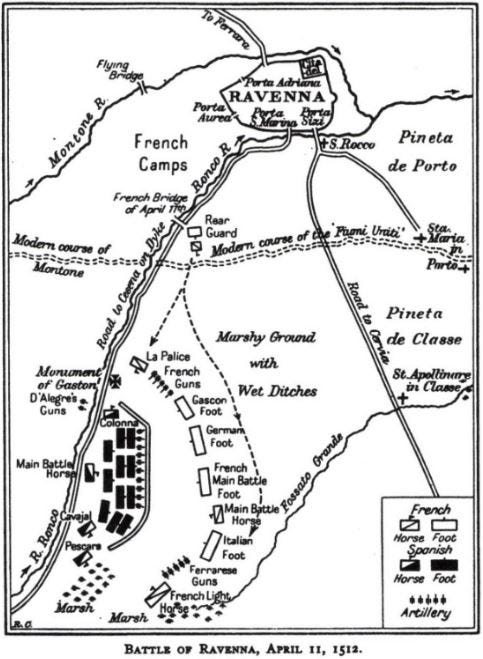

In some sense, these formations may have allowed battles to take place in the open. Well-organized and disciplined armies could maintain good order as they retreated in the face of a loss, making an outnumbered general more willing to risk battle in the first place. Most pitched battles of the early 16th-century involved one army protected by some barrier: fieldworks, as at Cerignola (1503), Marignano (1515), or Bicocca (1522); a natural obstacle, such as the river Garigliano (1503); or a provisional obstacle, such as the embankments at Agnadello (1509).

Holding a Reserve

One other factor ensuring the safety of an army was the reserve. As discussed in part 1, a true reserve—as distinct from a second or third line—is committed wherever it is needed at the sole discretion of the commander. For armies entrenched behind a barrier, that role was served by the cavalry: either to beat back any breakthroughs or flank attacks, as at Bicocca, or to pursue a broken enemy, as at Cerignola. On open ground, most of the cavalry was deployed on the flanks, while the large infantry formations drew in most of the foot soldiers. That left a few cavalry squadrons deployed behind the center to shore up a crumbling sector or drive home success. Less commonly, that role could be filled by a small group of arquebusiers to add their firepower where needed. At Marciano, the Florentines held a few hundred arquebusiers in reserve, both mounted and on foot, although they do not appear to have played an important role in the battle.

Occasionally, a rearguard was posted some distance behind the lines to guard the line of retreat, which could also function as a reserve. At Ravenna, the French left a rearguard to secure the bridge over the river Ronco in case the garrison should sally out during the fight; it subsequently played a critical role in the battle when it shored up the right as it came under heavy pressure. During the campaign leading to the Battle of Nieuwpoort (see next section), the Spanish also held a sizable reserve, but this was left guarding a bridge 15 km to the rear and was unable to influence the battle.

The Rebirth of Lines

As armies grew in size and as their battalions shrank, another factor influenced tactical deployments: an increase in firepower. Heavier muskets introduced in the later 16th century had greater range and accuracy, impelling commanders to increase the proportion of gunpowder to pikemen. This begat the question of how to deploy the infantry to maximize the effectiveness of that firepower.

The Dutch were the first to seriously experiment with this. Maurice of Nassau introduced reforms at the end of the 16th century that shrank battalions to about 600 men of equal parts pike and shot, arranged just ten ranks deep. Musketeers were placed on either side of a central rectangle of pike, and drills made their firing more efficient. These were explicitly modeled on the cohorts of Roman legions, and were drawn up in lines that seem to have functioned in a similar manner: each line maintained its integrity, fighting as one and allowing forward lines to safely withdraw when they were tired or beaten.

Maurice’s new system was first put to the test at the Battle of Nieuwpoort in 1600, when his army faced a Spanish army of similar size. The Dutch drew up in three lines of several battalions each, while the Spanish arranged four large battalions—each over 30 ranks deep—in a diamond. But in order to attack, the Spanish battalions had to come on line, negating any advantage of their deep array. The cavalry fight was a different matter: the movement of horses is much more fluid than that of men and required more time and space to reform, so it had long been common for smaller squadrons to deploy in multiple lines—both sides deployed most of their cavalry in three lines on the Dutch right/Spanish left.

The Dutch infantry acquitted itself well, but did not definitively prove its superiority. It fought on rolling dunes that obscured fields of fire and made it difficult to move in formation. The decisive action was fought by the cavalry on flatter and firmer ground to the south: once the Dutch horse defeated the Spanish, they turned to attack the tercios’ flanks and rear. It must be said, however, that the Dutch second-line battalions relieved their first-line compatriots during the exhausting fighting on the sandy dunes, and it was the fresh second line that delivered the final charge in concert with the cavalry.

The Turning Point at Rocroi

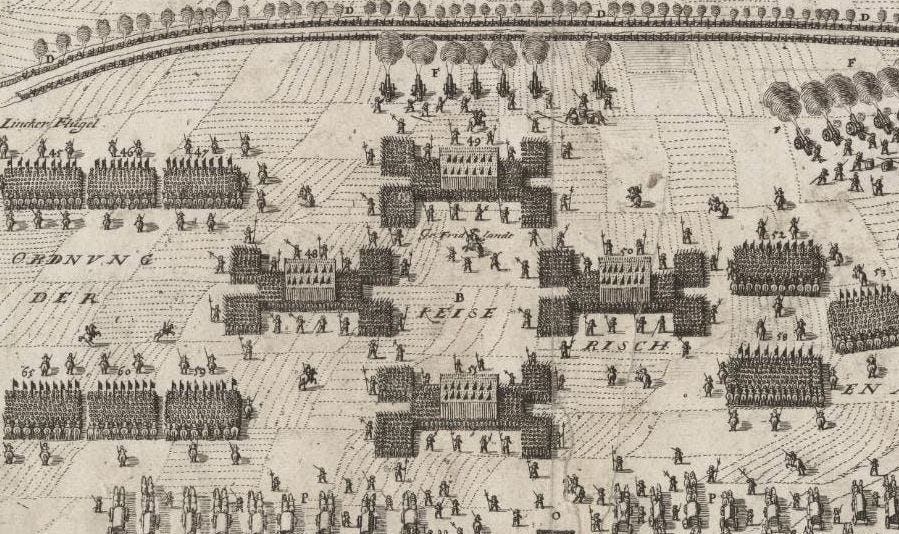

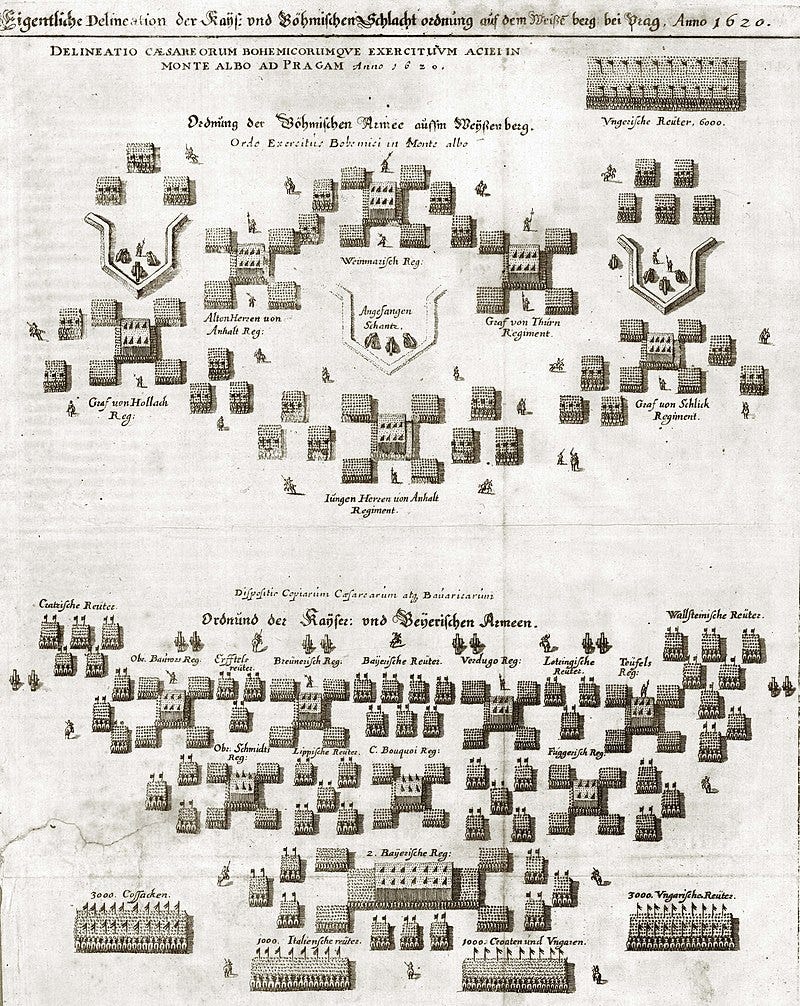

Spanish and Imperial armies continued to deploy in deep formations over the next several decades, but they grew thinner over the course of the Thirty Years’ War. By the time of the Swedish intervention in the 1630s, the principle of two-line deployments was well established in most European armies, although the Spanish maintained deeper formations than most.

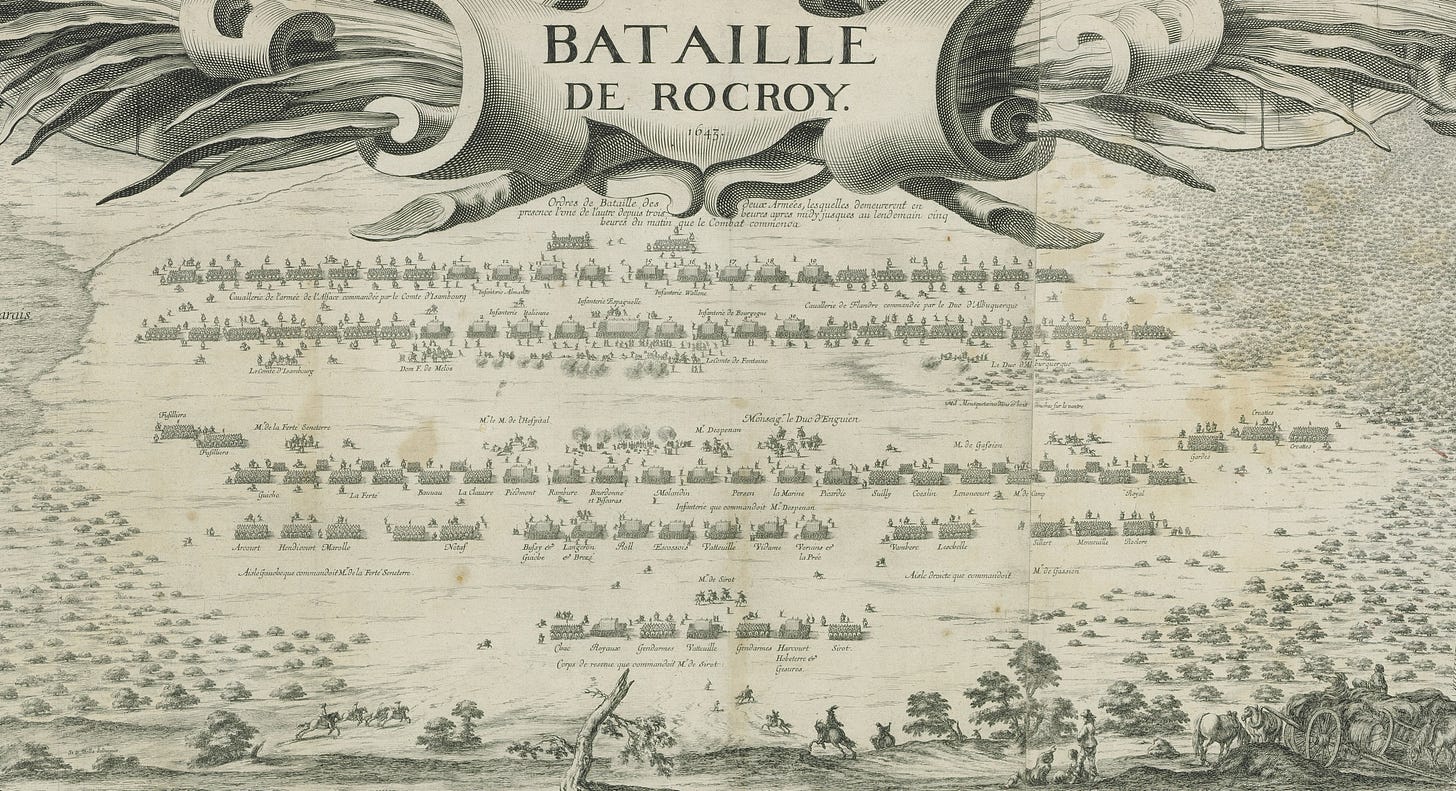

The Prince of Condé’s 1643 victory at Rocroi is a good illustration of this trend. More famous for signaling the ascendance of France over Spain, it was also a victory of thinly-arrayed French regiments over more conservative tercios. Both armies deployed in two lines, with the infantry in the center and cavalry on the wings. But where all French battalions were arrayed only ten deep, only the Spanish second line was deployed at a similar depth: first-line tercios were twenty ranks deep.

The Spanish held back a single large squadron behind their battle array, whereas the French held a mixed reserve: three infantry battalions placed in the intervals between four cavalry squadrons. This was drawn up behind the second infantry line, but it functioned as a true reserve: when the cavalry on the Spanish right opened the battle with a furious charge that nearly collapsed the French left, the reserve arrived just in time to drive them back. The French right meanwhile routed the Spanish left and swept around to attack the second line of infantry, whereupon it, the infantry, and the reserve fell upon the first line of Spanish infantry from all sides.

It would be too much to say that Rocroi was won by the more linear French tactics—like Nieuwpoort, it was cavalry that played the truly decisive role—although it did validate a trend that was well underway. More significant was the role of the French reserve, which shored up the left wing at a critical moment early in the battle and went on to help clinch the victory. Larger reserves, enabled by the thinner lines of this newly-emerging system, were becoming critical to victory.

The Extended Front

But it is never quite so simple. European armies took another leap in size in the second half of the 17th century as Louis XIV mounted a new challenge to Habsburg hegemony. The invention of the bayonet and increased accuracy of gunpowder weapons allowed generals to abandon the pike altogether, and they began deploying their musketeers in even longer, thinner lines which greatly expanded the extent of the battlefield. This would have important consequences on their ability to use reserves, which we will look at in part 3.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Please like and share if you enjoyed, it helps more people find this. You can also support with a paid subscription, supporters receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529 and get access to exclusive pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.

3000 men is roughly equivalent to a brigade/regiment and these deep formations actually include their own supporting ranks of men. So it’s a bit like a more modern brigade deploying “2 up, 1 back”