Lines and Reserves, Part 1: Tactical Depth in Antiquity and the Middle Ages

As far back as antiquity, generals recognized the importance of holding back a portion of their troops from battle. The arrival of fresh reinforcements at a critical moment—to shore up a crumbling position or exploit a gap in enemy lines—was so often decisive that the deployment of supporting troops became the central questions of tactics.

There have historically been two ways of doing this: deploying multiple lines in depth and employing a general reserve. Although the two are functionally very similar, they operate on subtly different principles. Whereas a reserve is committed during the course of battle at the sole discretion of the commander, secondary lines support the troops immediately to their front—only the timing of their commitment is left in question.

The two schemes are not mutually exclusive, however, and many generals throughout history employed both. Some tactical concepts moreover blurred the distinction between the two. Yet for the most part, the large infantry-heavy armies of antiquity depended almost entirely on multiple lines. This simplified command-and-control and avoided having to rush slow-moving infantry to a critical point. It is only with the more cavalry-centric armies of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages that we see the regular employment of a true reserve.

Lines of Battle

The Greeks are the first people whose tactics we have detailed knowledge of. For the most part, these were simple: they fought in a single line, typically 8-12 ranks deep, and held no reserve. Occasionally, a narrow section might be stacked 16, 25, or even 50 men deep in order to pierce the enemy line, but they had no way of exploiting this breach or shifting the main effort once the battle began. If one part of the line began to falter, there was little a commander could do to prevent it from turning into a wholesale rout.

The Greeks did use cavalry, typically deployed on either flank, which was mobile enough to be redeployed in a pinch. At the Battle of Delium, the Boeotians’ right, arrayed 25-deep, broke the Athenian left, while their own left began to falter. The Boeotian commander then sent some from his right to shore up the crumbling wing, thus winning the day.

Greek armies were small: only the largest battles involved several tens of thousands of troops. Over time, they incorporated different types of troops, including light missile troops and cavalry placed in front of the main line to screen its deployment and skirmish with the enemy. Other ancient peoples, such as the Persians and Egyptians, placed chariots or elephants in front to create breaches in the enemy’s line before the main attack. In all such cases, these foremost units aimed to create some effect in the initial phase of battle, but did not constitute a line of battle as such. Nevertheless, those larger states probably did arrange their armies in multiple lines.

We catch occasional glimpses of more complex arrangements among the Greeks too. Towards the end of the march of the Ten Thousand, some Persian forces appeared suddenly before the Greek army. Xenophon selected three units of two hundred men each and spread them out about 30 meters behind the line, so that if the enemy should break through at any point, a fresh and well-ordered body of troops could meet them. This fell somewhere between a line and a reserve: although too small to constitute a line as such (they were only 10-20% the total army) and presumably acting on their own initiative, they were each tasked in advance with supporting a certain sector of the main line. In the event, the Persians took flight at the Greeks’ advance and they were never needed.1

Alexander did similar at a grander scale at Gaugamela, where a larger Persian host threatened to outflank his less numerous Macedonians. Rather than stretch his forces thin by trying to match the Persian front, he formed a second line some distance behind the first: a body of cavalry and light infantry to the side of either flank, and a body of infantry directly behind the main phalanx.2 This way, he could protect against attacks on his flank or reinforce the center as needed. The formation proved successful: Darius tried to envelop the Macedonians on both flanks, which held out long enough for Alexander to lead a decisive attack in the center. The second line of infantry was successful in repelling a body of Persian cavalry which subsequently broke through the center to the baggage.

The Roman Innovation

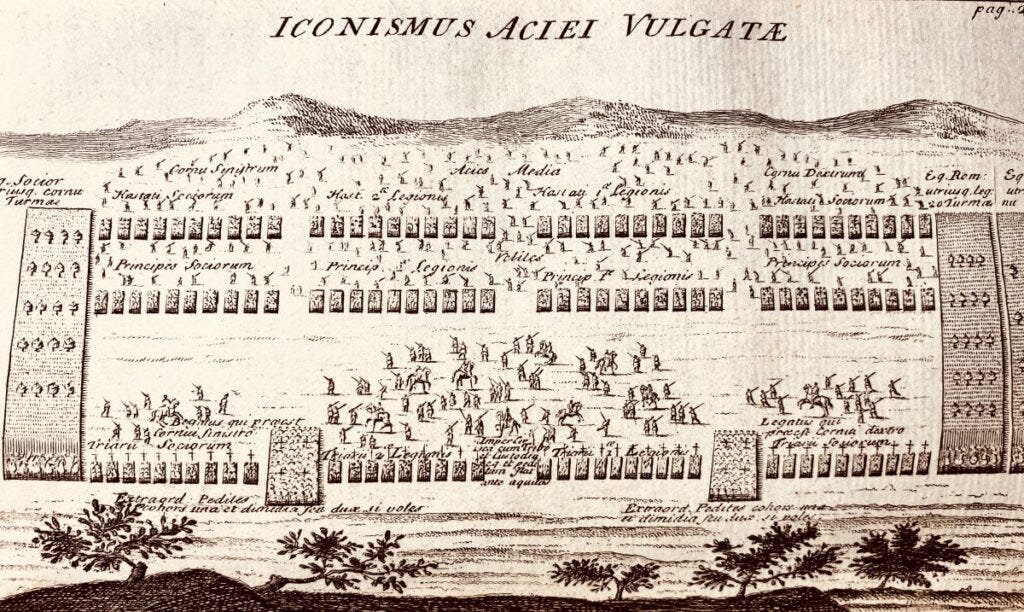

It was the Romans who, so far as we know, first used multiple lines of infantry in a systematic way. They formed their legions in three lines, called the hastati, principes, and triarii. A screen of velites, or light infantry, would skirmish with the enemy as the legion deployed.

Each line was composed of several blocs of troops: initially ten 120-man maniples, replaced by three or four 500-man cohorts in the late Republic. These were arranged in a checkerboard pattern that allowed the units of one line to pass through the gaps in another. If the first line was pushed back by an enemy attack, it could fall back to safety behind the second line; when the first line culminated in the attack, the second line could pass forward to continue the attack. And so in with the third line when the first two failed in either the attack or defense.

A few points of note. It was almost expected that the first line would fail at some point. Unlike Greek warfare, which came down to a question of which line would crack first, the Roman system put much greater weight on soldiers’ discipline in maneuvering formations and their commanders’ judgment in timing attacks. Roman tactics created a rolling attack in which each line crashed against the enemy in successive waves. This somewhat blurred the distinction between the tactical offense and defense: a rear line could charge into the attack even as a forward line was falling back.

This system proved especially successful against the Macedonian phalanx, a single line of men arrayed 16 ranks deep. Although the Macedonians might be able to crash through the first line with their long pikes, they gradually lost their impetus and cohesion as the legionnaires fell back and reformed, attacking gaps as they appeared in the line. The Roman system proved so successful that it quickly spread around the Mediterranean. As early as 202 BC, Hannibal arranged his infantry in three lines at the Battle of Zama—indeed, later Romans claimed that this technique came from the Spartans via the Carthaginians.3

Late Antiquity

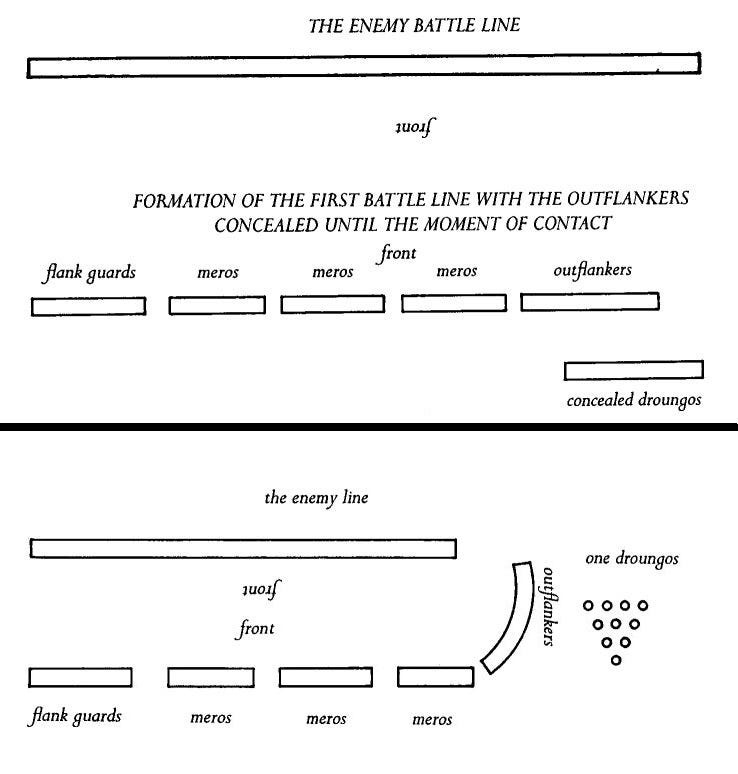

The Roman army continued to evolve through the Imperial period as conflict with the Persian Empire, Rome’s only great rival, spurred military innovation. Archers, heavy cavalry, and cavalry archers were integrated into increasingly complicated arrays. The greater mobility of these more cavalry-centric armies demanded new units to deal with contingencies: outflanker detachments guarding the right of the line, flank guards on the left, and ambush troops behind the right. The general’s bodyguard might function as a reserve of sorts, but for the most part the battle plan was written into the formation.

Interestingly, it was the Romans’ old Persian adversaries who most clearly employed a general reserve, as displayed at Dara, on the plains of northern Mesopotamia in 530. The Sasanian army drew up in two lines. On the wings, cavalry archers were positioned to advance to the attack then withdraw, one line relieving the other in a continuous rotation. Behind the main body were the Immortals, the elite heavy cavalry of the imperial bodyguard, who were held back from the action.

Opposite the Sasanians, the greatly outnumbered Romans drew up behind a trench. This was crossed by several paths which allowed them to sally out, and the center was U-shaped to conceal flanking detachments.4 The general Belisarius stood behind the main line with his bodyguard. It is not clear whether the Romans drew up in a single line or double—it is likely that infantry guarded the trench while the cavalry charged out. In any event, they made up for their weakness in numbers (half the enemy’s) with defensive works and outflankers.

An attack by the Sasanian right pressed the Roman left hard, but was eventually turned back by outflankers on both sides. After that, they made their main bid for success, committing the Immortals to an attack on the Roman right. This was not launched until the attack on the Roman left had already failed, however, giving Belisarius time to reinforce his right-center flanking detachment with the left-center and his own bodyguard. This slammed into the Sasanian left mid-charge, throwing it into disorder and forcing it back with heavy casualties.

The Battle of Dara shows the tactical sophistication of Late Antiquity in full bloom. Both sides fought in complex formations and both held general reserves. The Romans put more effort on the former, while the Sasanians favored the latter. The smaller Roman reserve may have been decisive, but only insofar as it reinforced the prepositioned outflankers. The Sasanian main attack, by contrast, failed because it was not synchronized well with their right wing, allowing the Romans time to regroup and shift forces.

The Middle Ages

This system remained in continuous use by the Byzantines through the Middle Ages. They continued to employ complicated formations and developing new ones as needed, faring well against a variety of different enemies. When their complicated system failed, however, it failed spectacularly—as at Manzikert, when the second line withdrew prematurely.

Western European armies imitated some of these tactics, especially during the Crusades. More commonly, they used different tactics tailor-made for their heavy-cavalry armies: a line of archers and spearmen, from behind which knights could charge out. As with skirmishers in ancient battles, the purpose of the infantry was not so much to serve as a separate line, but to screen the deployment of the rest of the army and soften up the enemy before the knights came into action. The cavalry typically fought in a single line, although it was not uncommon for the general to stand with his retinue in the rear as a reserve: from there, he could judge the time and place to launch a decisive attack.

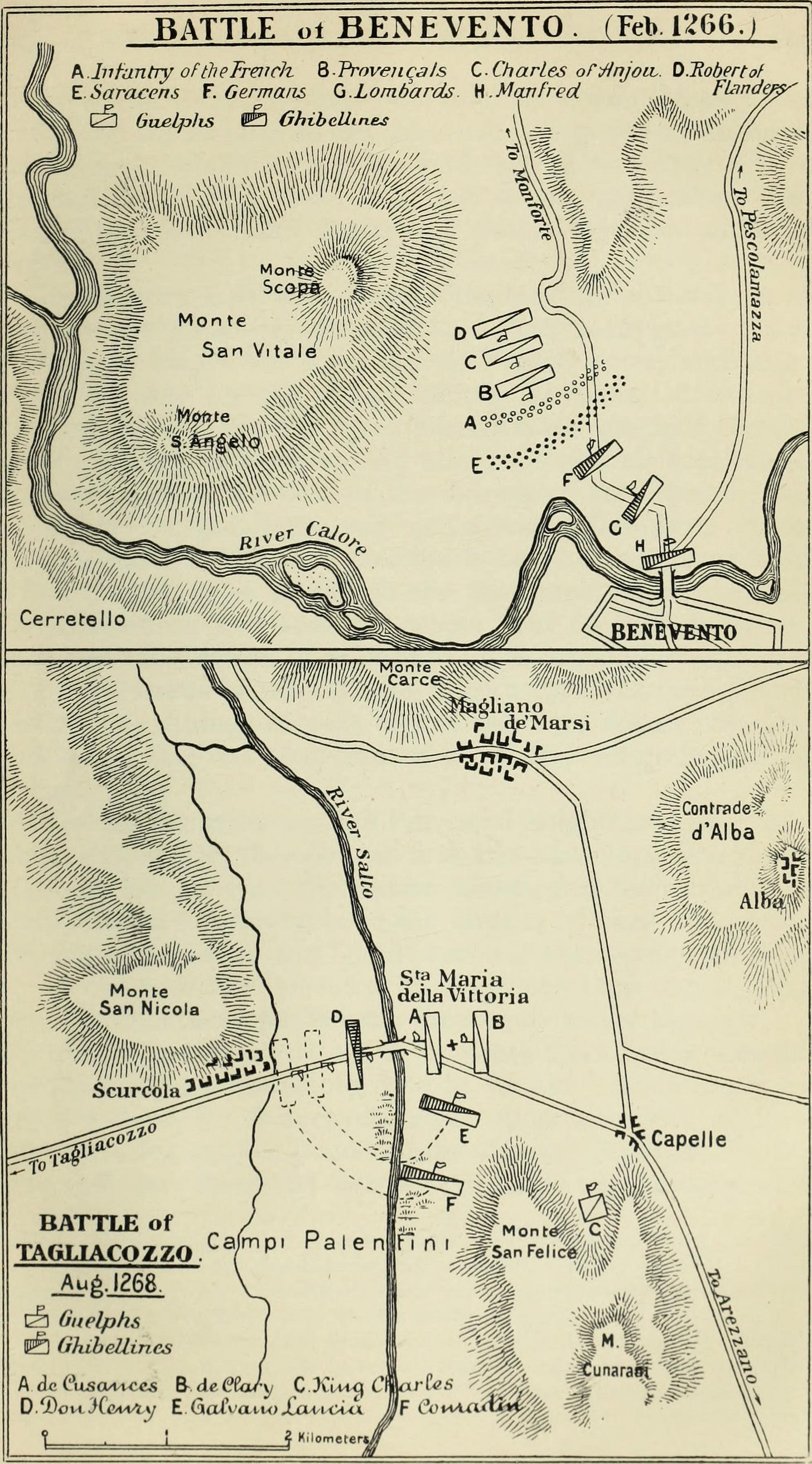

Occasionally, necessity forced medieval armies to employ deeper formations. During Charles of Anjou’s conquest of Sicily and Naples in the 13th century, he fought a pair of battles in the Apennine Mountains. At both of these, the restricted terrain forced the two sides to fight in multiple lines arranged in depth.

Poitiers

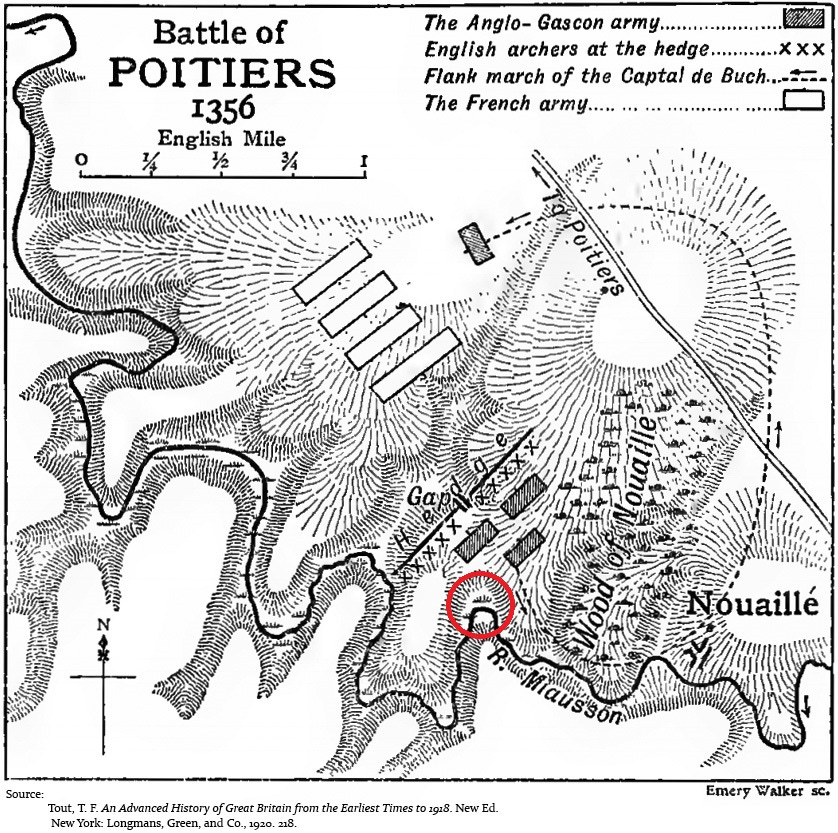

One of the most interesting battles of the Middle Ages was Poitiers, fought in 1356 during the Hundred Years’ War. This pitted an English army of about six or seven thousand against a French host roughly twice its size. It presents a useful study of one side employing a large reserve against another deployed in multiple echelons.

The French king John II had been pursuing the Black Prince, son of English king Edward III, for several weeks when he finally caught up five miles south of Poitiers. Short of provisions and with little chance of escape, the English drew up on a hill with a forest to their back. Their narrow front was protected by a dense hedge fronted by long rows of vines which afforded only a few openings, to which they added ditches, wagons, and other obstacles. Their right was anchored on the forest, while their left was protected by a marshy bend in a nearby river. The front was divided between two divisions: each consisted of about a thousand archers and several hundred spearmen emplaced behind obstacles, backed by a thousand dismounted men-at-arms. The rest of the army, including about a thousand mounted knights, stood behind them in reserve.

This presented the French with a challenge. They could not easily use their superior numbers, the majority of which were mounted men-at-arms, against a narrow, well-prepared position. John decided to dismount most of his knights and arrange them in three divisions which would attack in successive waves. The first of these was preceded by a small body of cavalry and crossbowmen tasked with clearing out the longbowmen so that the dismounts could close with the English men-at-arms.

The initial cavalry attack was a failure. The hedges along the English right prevented the cavalry from breaking through, while the archers on the left waded into the swamps to pour heavy fire into the cavalry’s flanks from close range. The knights and crossbowmen were thrown back, forcing the first line to begin its attack into the teeth of the English defenses. The heavily-armored dismounts were well-protected against the longbowmen’s arrows, however, and packets of men cut through the brambles to close with their enemy. After an hour or so of tough fighting, during which the Black Prince flowed reserves to threatened sectors, the first wave began to ebb.

As the first division pulled back, the second advanced. The dismounted French knights were not as well practiced as Roman legionaries in the smooth passage of lines, and the retreating troops threw the second line into confusion, sweeping them backward. Some inexplicably left the field altogether, while the rest joined the third division.

This left only a single division on the battlefield, under King John himself. He duly advanced to the attack and made difficult progress as the longbowmen ran short of ammunition. At this moment, the Black Prince made judicious use of part of his reserve, sending a hundred knights and eighty mounted longbowmen in a loop around the forest and behind the French left flank. They raised their banners as they moved into the attack, giving the signal for the rest of the English men-at-arms, now mounted, to charge into the enemy’s front. Assailed from two sides, the French line disintegrated into dispersed bands. These got trapped in a bend in the river, where most were killed or captured—including King John himself, who spent the remainder of his life in captivity.

The Battle of Poitiers is an excellent demonstration of both lines and reserves in medieval warfare, but it does not demonstrate the innate superiority of one over the other. Both sides chose tactics well-suited to their particular circumstances; the English simply executed better. If the second French division had not gotten disrupted, or if either of the first two divisions had remained on the field to support the third, the battle most likely would have gone the other way.

Toward the Gunpowder Age

Compared to the Roman system, which employed fairly standardized tactics across a vast empire, the military techniques employed in medieval Europe were far more varied. Each kingdom, lordship, and city-state used formations appropriate to local geography and the troops available. It was not until the High Renaissance that new weapons birthed new tactics which swept across Europe. We will look at this in Part 2.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Please like and share if you enjoyed, it helps more people find this. You can also support with a paid subscription, supporters receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529 and get access to exclusive pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.

Xenophon Anabasis, 6.5.

Arrian Anabasis, 3.12. Historians almost universally interpret this section as saying that the troops on the wings were angled back from the main phalanx. This stems from a misinterpretation of ἐς ἐπικαμπὴν: they were not formed diagonally, but were positioned at a spot diagonally backward from either wing, as the rest of the text makes clear. In the first place, Arrian is explicit that the three bodies behind the main line—the two on either wing plus the baggage guard—formed a second line (δευτέραν τάξιν). Secondly, he states that this allowed Alexander to either extend or deepen his front as needed: i.e. to move the wings forward or pull them behind the main line. Thirdly, Alexander shifts his entire army to the right as the battle begins—this simply would not have been possible for troops formed at an angle.

Vegetius De Re Militari, 3.17. This would have been via the Spartan Xanthippus, who trained the Carthaginian army during the First Punic War (264-241 BC). Although Vegetius wrote around 400 AD, nearly 700 years after the fact, we have no reason to doubt his claim: descriptions of the early Carthaginian and Roman armies are simply too sparse to judge. There is indirect evidence that the idea of posting a second line originated in Sparta, however. After returning from the expedition of the Ten Thousand, the Athenian Xenophon fought with the Spartans and was consequently exiled from his home city. His subsequent writings praise the Spartan constitution and military system. Scholars have furthermore noted that his Anabasis and Cyropaedia seem to have been written partly for didactic reasons: Xenophon’s description of his own tactics could very likely have been an oblique reference to Spartan practice.

Nevertheless, it remains likely that the Romans perfected this system. At Zama, each line was composed of completely different troops: Spaniards and northern Italians in the first, Africans in the second, and the veterans of his Italian campaign in the third. The Roman system was different: armies deployed their legions in a single line, with each legion formed into three lines. That way, soldiers were supported by their fellow legionaries who they lived and trained with, not complete strangers.

Procopius History of the Wars, 1.13. Some historians have the U-shaped section projecting outward, with the outflankers to either side. The text is ambiguous, but Procopius states that the inner section was a very short distance in front of the gates of Dara, suggesting the wings of the trench could not have been closer.

Very interesting read!

Unit formations on the battlefield also reflect as a key factor what weapons the men carry. The long pikes carried by Greek hoplites defined both how close they had to get to the enemy to wield their pikes in a lethal manner. The Roman legions needed to get up close and personal with their short swords to be lethal, and they used a tight formation and the close protection of their shields to protect themselves as they wielded those swords in brutal fashion against the enemy. Later, in the gunpowder age, the matchlock musket saw its bearers in a rather lose formation giving each man about 3 feet around him in which to maneuver his musket, its rest (until that was abandoned as the muskets got lighter), and a lit match of several feet in length which provided the critical spark needed to ignite the musket's powder and propel its lead bullet towards the enemy. Flintlocks enabled the soldiers to move into a shoulder to shoulder line of men who could fire and huge volley at the enemy.