Naval Warfare is Positional: The Influence of Land on Sea

Operations on land usually determine the objectives of a naval campaign, but the reverse is also true: the ability to project power at sea is determined by territorial control. Naval operations require safe harbors, refueling station, airfields, and so forth. Throughout history, the defense or acquisition of these—securing the ability to generate force while neutralizing the enemy’s—has almost always taken priority over engaging enemy naval forces directly. In a very fundamental way, therefore, naval warfare is positional.

This is counterintuitive. After all, the wide-open ocean offers near infinite expanse for two fleets to sail out and meet in combat. Yet general fleet actions—already exceedingly rare—are almost always fought around a larger territorial objective. Battles such as Jutland, Trafalgar, or Beachy Head, in which sea control is the immediate objective, are the exception within the exception.

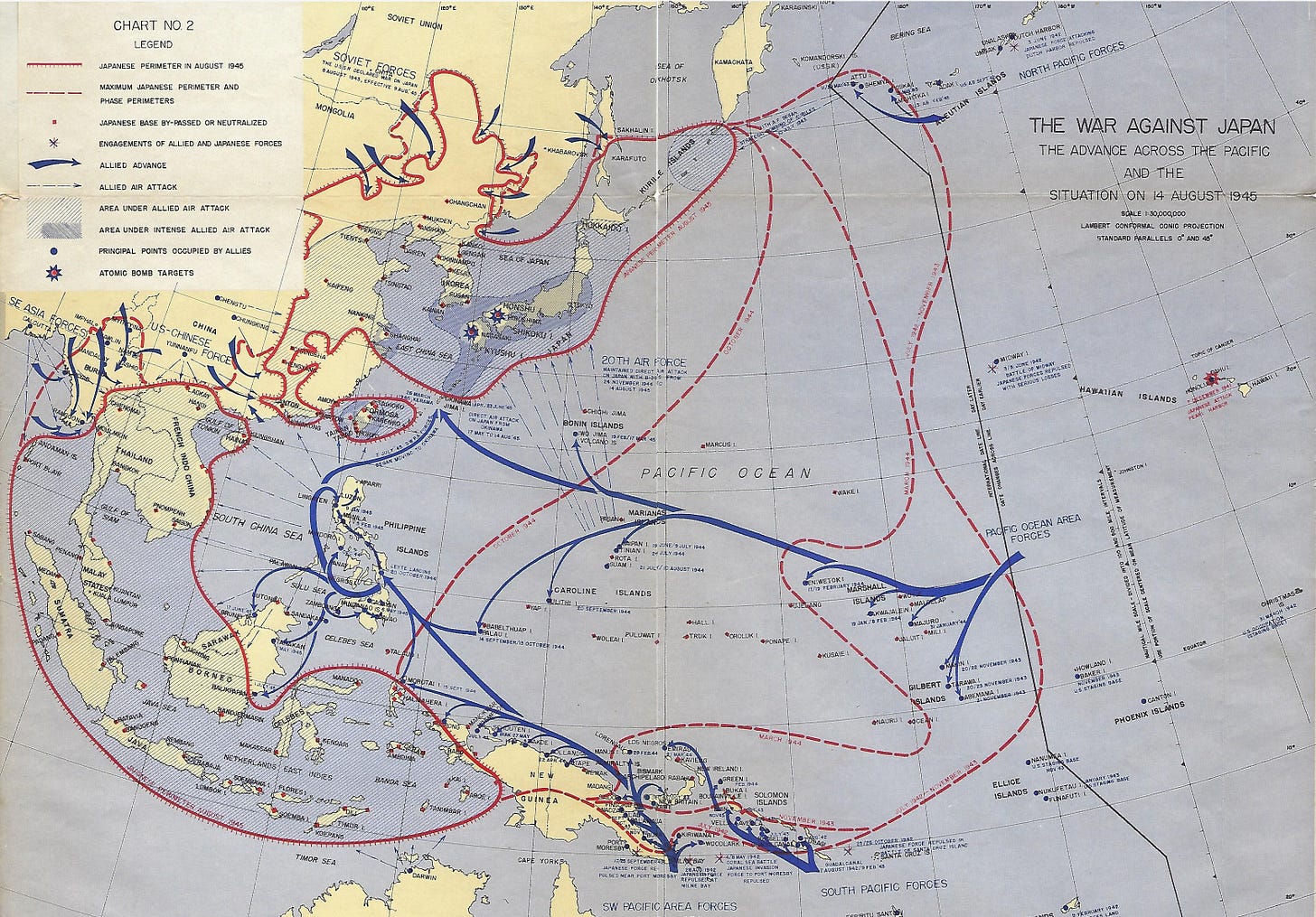

So much has been obvious since World War II. The American and Japanese navies could not simply sail out and fight each other in a climactic battle, as some had envisioned. Any enduring progress across the vast expanses of the Pacific could only be made with the support of airfields and refueling stations—geographic points that had to be conquered and maintained. In the campaigns for these points, naval battles occurred as merely one element, not the other way around.

This is all the more so in the missile age. The ranges at which modern shore-based systems can strike ships means that any nautical action must focus first and foremost on geographical points: to eliminate enemy batteries, to establish anti-missile and -ship umbrellas, to emplace radars and airfields, etc. In practical terms, it is outright impossible for a purely fleet action to occur at scale.

The Naval Campaign

This becomes more intuitive once we realize that, as on land, the campaign is more fundamental than the battle. In fact, this is even more true at sea: battles are so rare because they are not essential for the objectives of the campaign. Oftentimes, those objectives are poorly served by battle.

The purposes of naval forces in wartime goes far beyond the destruction of the enemy fleet: protection of one’s own shipping, destruction of the enemy’s, supplying outlying positions, landing troops, bombardment of land targets, blockades, etc.

Added to this are two generalities that stand somewhat in contradiction to each other: the great difficulty of destroying a fleet and the tremendous risk of losing one’s own. Precisely because fleets are so useful for many other functions, a weaker one will not venture out into the teeth of a much larger force. Any defeat would represent a tremendous loss of invested hardware and hard-to-replace skilled personnel. At the same time, even when two fleets do meet in combat, it is difficult for one to shatter the other: for every one Lepanto, Trafalgar, or Tsushima, there are many more Texels, Málagas, or Jutlands.

This is amplified by the constraints of geography. Fleets cannot remain on station indefinitely, and must have protected positions in which to concentrate for major operations. Although a fleet has more freedom than an army in choosing its path from point to point, the number of key nodes is far smaller: as a result, it is often more economical to target those points.

Maneuver at Sea

These positional dynamics are remarkably consistent throughout history, even as the specifics of navigation have drastically changed. The oared sailing vessels of antiquity and the Middle Ages, for instance, were technically capable of crossing open water, but still had to land once every few days to replenish food and water—in practical terms, this limited their routes to narrow bands along the coast. During the First Punic War, Romans and Carthaginians had to sail along either Sicily or Sardinia and Corsica to reach the other; much of the naval combat was therefore focused on capturing bases on those islands.

This also meant that it was very easy for one ancient fleet to intercept another as it followed narrow, predictable routes which were easy to block. At the Battle of Cape Ecnomus, the largest naval battle of antiquity, the Carthaginians attacked a Roman fleet en route to Sicily’s western tip for a landing in Africa. They did this by simply waiting off the southern coast in between the two coasts—the equivalent of occupying a crucial pass and forcing the enemy to lodge one out (which, in the event, the Romans did quite successfully, sinking or capturing over a quarter the Carthaginian fleet). Although the battle tactics themselves were quite fluid, at the operational level it was straightforwardly positional.

The Age of Sail

Large, ocean-crossing sailing ships gave admirals more room for maneuver, but operations continued to be shaped by key geography. Britain’s rise to maritime dominance illustrates as much. During the Anglo-Dutch Wars of 1652-74, the two powers wrangled for control of the North Sea in several open-water engagements, while also conducting positional operations: blockades, amphibious landings, and engagements off major objectives. During the long rivalry with France in the following century and a half, by contrast, the two fleets deliberately met in general engagements only twice: at Beachy Head and Barfleur in the 1690s.

In these two battles, the French aimed to sweep the English Channel of enemy ships in advance of an invasion—a direct bid for sea control. After that point, many battles supported sieges of key fortresses: the Battle of Málaga during the 1704 siege of Gibraltar, for instance, or the 1756 battle off Menorca protecting the French landing. At others, where the immediate British objective was the destruction of the French fleet (e.g. Toulon or Quiberon Bay), battle was only precipitated by their quarry’s attempt to slip a blockade—that is to say, the result of a campaign of position.

The great exception to all this was the Trafalgar campaign, in which Nelson doggedly pursued Villeneuve’s Franco-Spanish fleet back and forth across the Atlantic before destroying it off the coast of Spain; but even there, the maneuvers of the campaign were shaped by an ongoing blockade of the remainder of the French fleet at Brest.

The Age of Steam

Wars over the following century were fought on a smaller scale, which made contests for limited sea control more feasible. There were several open-water battles not oriented toward a geographic objective:

Sinope, 1853, between Russians and Ottomans for control over the Black Sea at the outset of the Crimean War.

Yalu River, 1894, for control of the Yellow Sea in the First Sino-Japanese War.

Tsushima, 1905, for control of the Sea of Japan in the Russo-Japanese War.

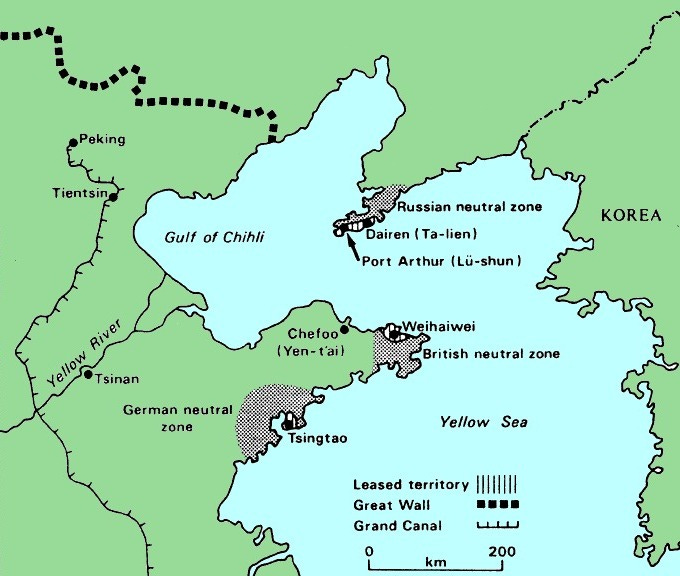

Naval operations in the two Japanese wars were certainly oriented more toward sea control, but also entailed support to amphibious landings (in the Pescadores) and ground objectives (Port Arthur). In the Crimean War, naval operations were characterized far more by Anglo-French support to ground forces in the Crimea and a blockade of Baltic ports.

Other wars remained overwhelmingly positional. After Trafalgar, the most notable battle of the 19th century was Lissa in 1866: the first battle between large numbers of ironclads as the Italians tried to open the way for a landing on Austria’s Dalmatian coast. The Greek War of Independence in the 1820s likewise saw several large engagements around blockades of ports and access to islands, while the two great battles of the Spanish-American War were for key ports in Cuba and the Philippines.

Revealing too are the wars that didn’t happen. The prospect of a renewed contest for maritime hegemony prompted a scramble by Britain, the United States, France, Germany, and other powers to establish a network of coaling stations around the world to sustain globe-spanning operations. Competition for key points inflamed tensions among the powers, especially in the Pacific. Key terrain was not just an important factor within naval warfare, but several times nearly occasioned hostilities.

Operational Effects of Land-Based Positions

If naval campaigns are therefore positional in a broad sense, there is one specific way which is especially important: the ability of certain geographic points to influence operations at sea. The French fortress of Louisbourg, which guarded the entrance to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, is a prime example. Although its guns came nowhere close to ranging the mouth—over 100 km at its narrowest—it could harbor a flotilla which could threaten any amphibious force that tried to land.

As such, before the British captured the strategically valuable Quebec, they took Louisbourg in a land-sea assault in 1758. A small French squadron sheltered under the guns of the fort, but a combination of British shore batteries and longboat raiders destroyed them.

Port Arthur played a similar role in controlling the 100-km-wide entrance to the Bohai Sea, a large gulf which gives Beijing access to open ocean. This made it a key Japanese objective during the Russo-Japanese War, and the fleet supported the army’s siege, trapping the Russian Pacific Fleet in harbor.

Critically-sited ports have always been able to shape naval operations around key chokepoints, but as shore-based weapons improved, they were increasingly able to do so even without any naval forces of their own. British Gibraltar, a perennial frustration to enemy movements between the Atlantic and Mediterranean, by World War I had guns powerful enough to range the entire Strait. The Turks closed the Dardanelles with a combination of naval mines and shore-based batteries, as did the Russians in the eastern Baltic.

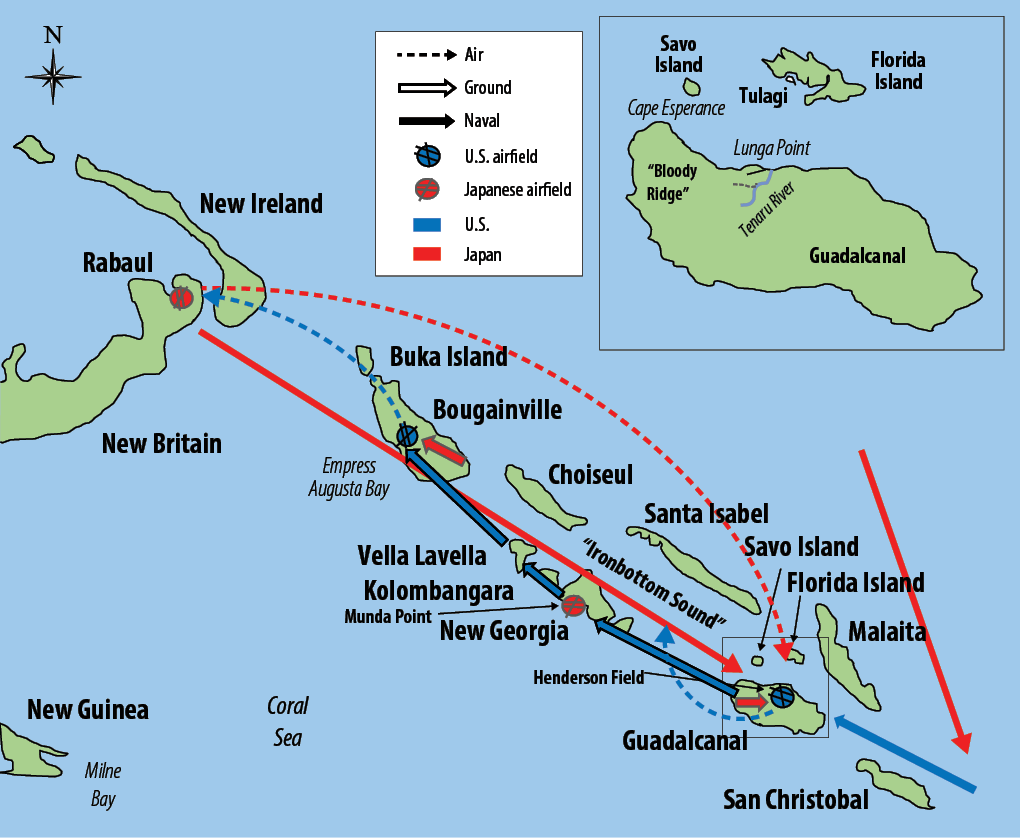

It was the advent of air power in World War II, in which planes which could strike targets hundreds of kilometers away, that forever changed naval warfare. No longer could squadrons simply cruise enemy waters looking for a fight. The danger of enemy aircraft meant that every move had to be orchestrated with an eye to outlying islands: operations had to be rapid, with ample escorts, and focused on seizing the objective quickly with an eye to getting one’s own shore-based aircraft operational.

The most complex of these were those around Guadalcanal, where both sides had naval forces, ground forces, and land-based aircraft concentrated within a relatively small area. So much weight was given to the influence of land-based aircraft that they determined US objectives throughout the central Pacific, while the one battle designed to precipitate a decisive fleet action—Midway—was baited by a Japanese assault on an airfield just 2000 km from Pearl Harbor.

The missile age only exaggerates these dynamics. Current weapons can strike ground targets several thousands of kilometers away and create anti-air and anti-ship bubbles hundreds of kilometers wide. The question of sea control around any objective of strategic value is now dominated by key terrain. Merely sailing within an enemy’s missile and aircraft engagement zones requires careful consideration, and any decisive campaign would entail numerous fights for position.

On Open Water

There has been one major exception in this discussion, and that is commerce raiding. Attacks on enemy merchant shipping, whether to capture them as prizes or to cut off critical supplies, have always been a major part of any war between maritime powers. These could result in quite large engagements in open water between attacking squadrons and convoy escorts. Carthaginians attacked Roman shipping in the Tyrrhenian Sea, while corsairs during the Age of Sail prowled sea lanes in the Caribbean, Mediterranean, and North Sea. German submarine wolfpacks terrorized Allied shipping in the Atlantic as American subs did the same to the Japanese in the Pacific. During the Iran-Iraq War, both sides attacked each other’s oil tankers in the Persian Gulf.

Targeting enemy ships in open waters put a premium on intelligence. News of arriving convoys (whether via intercepted communications or espionage) informed patrol routes, while raiding squadrons pushed out fast vessels or aircraft to scout. In the 21st century, satellites, UAVs, and sonar buoy networks, making it increasingly difficult for ships to protect themselves by hiding in the blue expanse.

The obvious response is convoy escorts that can defeat long-range systems. Such resources are always scarce in a wartime environment, which will only create further demand for persistent protection of holding zones around friendly waters. In this way, even the nature of blue-water combat reinforces the logic of position.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

“a fleet in being”

I enjoyed this. This morning, we highlighted an article published in Military Review that discusses the importance of Army Fires in the maritime domain and draws comparisons to Guadalcanal and the rise of China.