Sea Power in Continental Wars: Naval Strategy Under Louis XIV & XV

The great 15th-century voyages of discovery which inaugurated the Age of Sail also opened new fields of competition to European powers. Spanish gold and Portuguese spice provoked the envy of other powers, and soon Dutch, English, and French corsairs were raiding their overseas convoys. By the end of the 16th century, the northern powers tried to muscle into the colonial game, and began attacking their distant colonies.

These early conflicts at sea were only loosely connected with affairs in Europe. France’s rivalry with the Habsburgs in Italy gave pretext for the first capture of a Spanish treasure fleet in 1522. The long Dutch revolt against Habsburg rule (1566-1648) saw naval actions against the Spanish and Portuguese, while Spanish tensions with England led to famous privateering exploits of Walter Raleigh and Francis Drake. Yet for the most part, sea and land were two separate domains. There were only a few examples of one affecting the other: Dutch naval ascendance forced the Spanish to send troops to the Netherlands via an overland route, for example, and Spain could only rarely threaten England with invasion.

By the late 1600s, this picture had drastically changed. Wars on the continent were fought on a scale that exceeded even the heights of the Italian Wars, as Louis XIV’s ambitions polarized Europe into large coalitions. England, France, and Holland had meanwhile formed substantial navies and colonial empires of their own, giving these wars a strong maritime complexion—both in how sea power affected land operations, and how colonial rivalries affected strategic decision-making.

Sitting squarely at the intersection of land and sea power was Bourbon France. Under Louis XIV, her army grew to become the largest in Europe, making her ascendant in the long rivalry with the Habsburg Austria and Spain. Louis also undertook a great expansion of the navy, which briefly became the most powerful in the world and thereafter maintained a consistent second place to England. The Anglo-French naval rivalry played out over 75 years of intense competition, against a backdrop of four titanic wars on the continent. Taken as a whole, this period demonstrates the complex ways in which sea power affects affairs on land.

The Roles of Sea Power

It is always tempting to treat the maritime domain as something separate from land. Its battles and campaigns are governed by a completely different logic. Navies also require specialized skills and enormous capital investments that take years to develop—they cannot be mobilized and demobilized like conscript armies. The ocean is like a second front, with all the downside of dispersing efforts yet none of the ability to transfer forces from one to the other. It would therefore be tempting to describe wars at sea as almost entirely separate from those on land, as parallel conflicts united only by the powers involved.

Nevertheless, there was some overlap. Sea power served three major objectives:

1. Conquest and defense of colonies

2. Attacking and defending commercial shipping

3. Supporting land forces in Europe

All three affected wars on the continent, either indirectly or directly. The colonial trade was responsible for upwards of a third of maritime states’ gross revenues, influencing their ability to finance a military buildup. Commerce raiding and the blockade of ports was a form of economic warfare that hurt the enemy’s ability to pay for the war, while defraying the aggressor’s expenses through the capture of valuable prizes—this made war costs unsustainable in the long term and increased domestic pressure for peace. Finally, navies could at times assist land operation directly, whether by landing troops or providing artillery support. Thus, from a land power’s perspective, navies served grand strategic, strategic, and operational ends, respectively.

The Rise of the Northern Maritime Powers

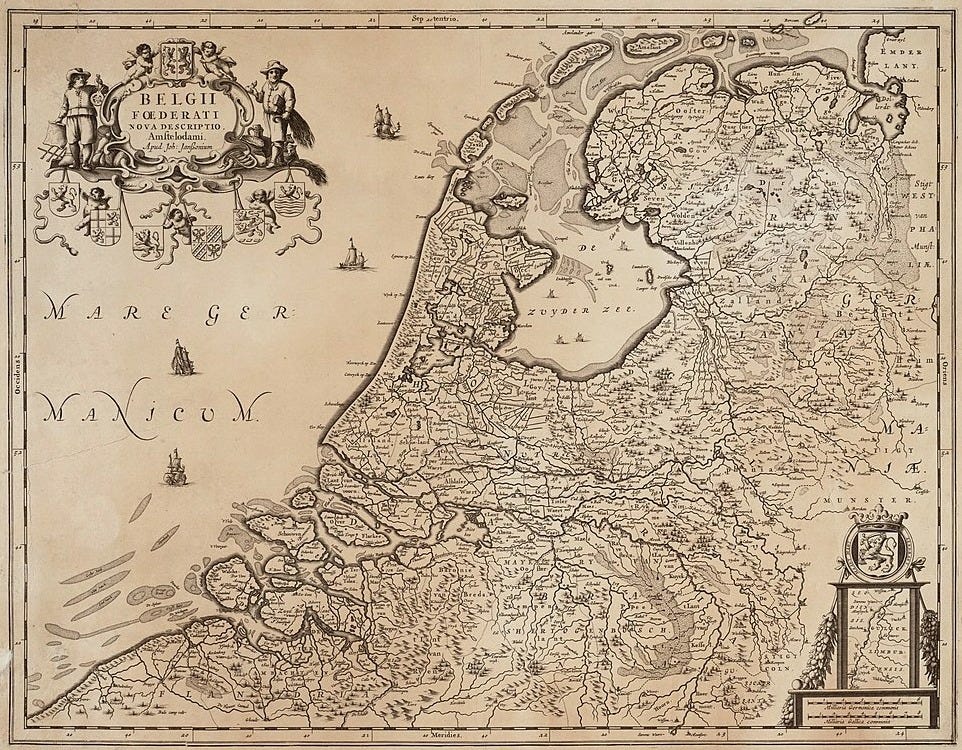

For much of the early period, however, sea power was mostly disconnected from fighting on land. It was only as Europe’s maritime center of gravity shifted northward that it got truly integrated into wars on the continent. The Dutch were the first of the northern powers to build a sizable fleet during the Eighty Years’ War, their long war of independence from Spain. Their naval resources were minimal early on, but they quickly built up a war fleet to contest the North Sea, forcing Spanish troops to travel to the Low Countries by a difficult and expensive overland route.

This protracted land war, which caused five sovereign defaults over its length, naturally led to a decline in Spain’s maritime power. The carrying trade was increasingly contracted out to Genoese ships, and colonial revenues gradually declined as the influx of precious metals into Europe caused their value to decline. Portugal, which was held in personal union by Spanish kings for most of the war (from 1580 to 1640) suffered a parallel decline.

The Dutch, on the other hand, by merely holding out on land (with occasional French and English assistance), could turn to the sea with nearly unlimited upside. Their privateers preyed on enemy shipping, aggravating their fiscal precarity, and seized colonies in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. They used their navy not only to defend home waters, but to assist with sieges of coastal and riverside fortresses. The Dutch Revolt is the first major example of navies being systematically used to pursue all three objectives of sea power.

Protestant England and Bourbon France greatly expanded their own navies during this time. By 1648, which marked the end of the Dutch Revolt and the Thirty Years’ War, all three northern powers had established colonies and trading stations in North America, the Caribbean, and along the African coast, while the Dutch held colonies in the Indian Ocean and Far East. This expansion triggered competition, especially between the United Provinces and England, which fought a war every decade from the 1650s to the 70s. These were mostly inconclusive, fought in the North Sea and more distant waters with little net change of territory—the most significant result was the capture of New Amsterdam in 1664, which gave England a contiguous stretch of North America’s eastern seaboard. It was not until the third of these wars, when England joined France in an attack against the United Provinces, that maritime competition got enmeshed with wars on the continent.

Setting the Stage: The Anglo-French Attack on Holland

Competition among the three northern powers developed amidst a complicated political backdrop. In the United Provinces, two factions vied for power. The “republican” party represented the powerful merchant class, whose interests lay at sea. Opposed to them was the House of Orange, whose scions were the stadtholders—or chief officers—for five of the seven Dutch provinces; they commanded the Dutch army, and were more interested in European affairs.

The republican faction held power throughout the 1650s and 60s, which put the Netherlands at odds with England under both the Commonwealth and the Stuart monarchy. This antagonism became pronounced after the 1660 restoration of Charles II, whose nephew was William of Orange. France, by contrast, was allied with the Dutch republicans in the 1635-59 war with Spain, and saw them as a natural counterweight to England’s maritime power—Louis XIV supported them in the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

Things came to a head in 1667. Just as the war between Holland and England was coming to an end, Louis XIV launched a whirlwind attack on the Spanish Netherlands, capturing several fortresses and towns along his northern frontier—the so-called War of Devolution. The Dutch were alarmed to see their buffer whittled down, and formed a defensive alliance with their erstwhile English foes. Smarting from the rebuff, Louis sought revenge. He courted Charles, who, sensing an opportunity to cripple Dutch sea power, agreed to forsake his recently-formed alliance.

Louis and Charles launched a joint invasion in spring 1672. A large French army invaded from the south, while the Anglo-French fleet was to land an amphibious force in the west. The French army overran southern Holland and nearly captured Amsterdam, but the Dutch managed to open the dikes just in time, creating an impassible water barrier. The republican government, which had sought to appease the French, was overthrown, and William of Orange assumed power. He mounted a vigorous defense, repositioning most troops to prevent an allied descent on the coast.

Throughout 1672-73 the Dutch fleet hung within the protection of the many inlets and sandbars along their coast, only venturing out to launch limited spoiling attacks. Although never able to defeat the larger allied fleet outright, they were able to repeatedly inflict enough damage that their adversaries had to withdraw to home port to refit. Dutch diplomats were meanwhile busy. In August 1673 they concluded an alliance with Spain and Austria, turning the war into a wider European contest. Charles, under pressure at home for supporting Catholic France against Protestant Holland, withdrew from the war early in 1674, leaving Louis to fight alone; his armies proved their worth, however, overrunning parts of the Spanish Netherlands, Lorraine, and the Franche-Comté.

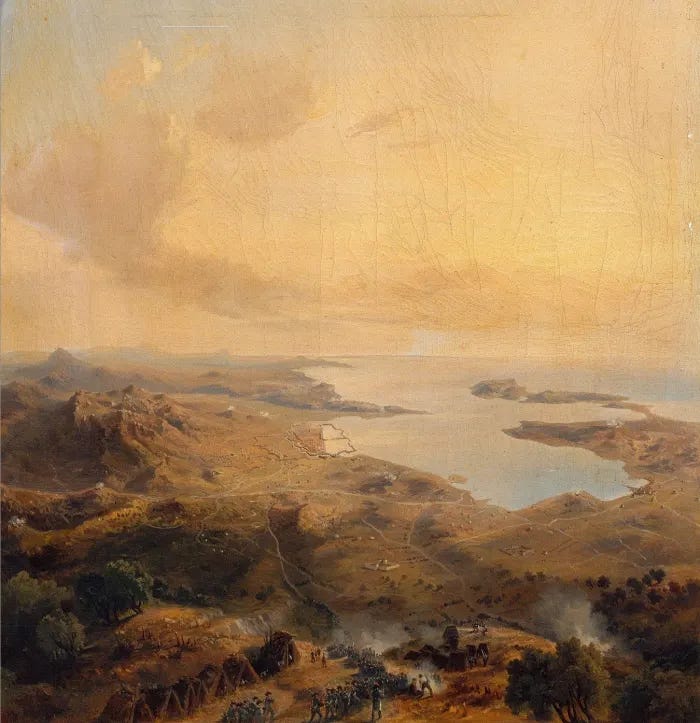

The only theater where he held no advantage was at sea. But with the English out of the picture, the Dutch drew down their fleet, allowing Louis to loose his privateers on their shipping. And the French navy remained strong enough in the Mediterranean to support a rebellion against Spanish rule in Sicily, overcoming several attempts by a Dutch-Spanish fleet to stop them—only the threat of English entry into the war in 1678 against her former ally forced Louis to seek peace. The Dutch, whose commerce was harmed by the war and who were moreover subsidizing many of the German states, readily agreed: peace was signed that year in a series of treaties at the city of Nijmegen.

The Dutch war was a prototype for the use of sea power in the larger continental wars to come. England and France attempted, but did not succeed, to use it in support of operations on land; once that failed, the French navy was reduced to privateering and to supporting limited operations in the Mediterranean. There was also some action in the colonies: the Dutch reoccupied New Amsterdam/New York in 1673, attempted to seize Martinique, and briefly held French Acadia.

Although France came out with significant territorial gains, the war also had several long-term negative consequences. It weakened Holland to England’s benefit, confirming the gains of the first two Anglo-Dutch wars, and brought the hostile Orangist faction to power. They already had family ties to the Stuarts, and in 1677 William married Charles II’s niece Mary (daughter of the future James II), bringing the two foremost maritime powers together. Finally, by drawing several continental powers into common cause against Louis, it created the pretext for future coalitions. The stage was thus set for the next great war, in which France fought alone against all of Western Europe.

Naval Geography

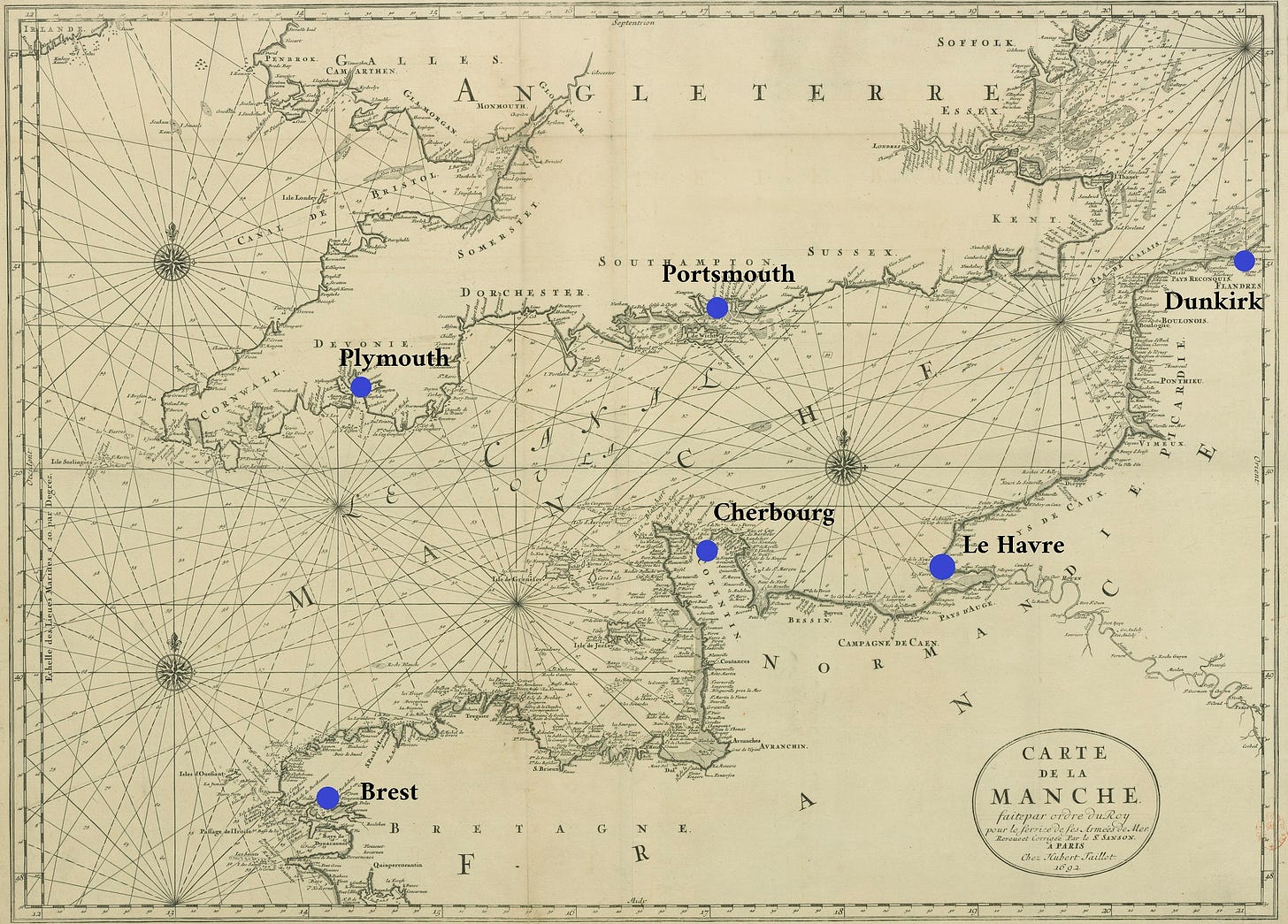

Relations among the northern powers were also shaped by the geography of the North Sea and English Channel. The rise of three maritime powers in close proximity made these waters of supreme strategic importance. Of first importance was the number and quality of naval stations available to each. A good port had natural protection against the elements and could easily be fortified, while being of sufficient size and depth to assemble a large number of warships. The Dutch were particularly blessed with sheltered anchorages. The Zuiderzee was a large inland sea protected from open waters by a chain of barrier islands. Along the southern coast, several rivers flowed into the sea with large estuaries that provided safe harbor and were difficult for unfamiliar sailors to navigate.

England had by comparison few such harbors on its east coast. Although there were several anchorages in which ships could assemble, there were few good ports south of Hull. This made the Thames estuary—and by extension London—vulnerable, a fact demonstrated by the 1667 Dutch raid on the Medway, a major dockyard off the estuary. On the southern coast there were several suitable ports, foremost of which were Plymouth and Portsmouth. Both had excellent natural harbors, and the latter opened onto the roadstead of the Solent (the channel between the Isle of Wight and the English coast), making it an ideal assembly area for descents upon northern France.

The French coast was not so fortunate. Le Havre and Cherbourg both had good harbors, but these were small, unable to shelter more than a few ships-of-the-line—they could be used as assembly areas, not permanent naval stations. Dunkirk was even smaller, suitable only for shallow-drafted vessels, although its location near the Strait of Dover made it an ideal privateering nest. These disadvantages were somewhat offset by Brest on the western tip of Brittany: this had a large harbor off a superb roadstead, making it the natural station for France’s Atlantic fleet.

Several other natural harbors along France’s western coast were used for commercial traffic, shipyards, and temporary naval stations. As a Mediterranean power, France also had a fleet stationed at Toulon in the southeast. Although this gave the navy flexibility, the 3,000-km voyage around the Iberian Peninsula from Brest and Toulon made it difficult to concentrate naval force.

This maritime geography shaped strategy on the continent. Although England’s wars with the Dutch were largely driven by commercial disputes, their top military priority was to secure their own eastern coast. As we saw during the Anglo-French war on the Dutch, the Netherlands’ coastline allowed even a weaker fleet to take shelter until the winds were favorable for an attack. England aimed to conquer several “cautionary towns” along the southern estuaries, which would prevent these from being used for military purposes.

Their failure to achieve this goal was compensated by Charles’ rapprochement with the Dutch in 1677. Thenceforth, their primary concern was to curb French expansion in the Spanish Netherlands. In the long run, France’s possession of the southern Low Countries would make Holland’s southern border indefensible, and could ultimately force them into an alliance against England. More immediate was the prospect of French control of the port of Antwerp on the Scheldt, the southernmost of the major rivers flowing into the North Sea. Its estuary was due east of the Thames, a large roadstead that could be used to assemble a blockading force or an invasion fleet. The 1648 treaty between Spain and Holland put the border across the river mouth, closing it to maritime traffic, but if the French managed to wrest control of Antwerp they would no doubt challenge this.

The use of sea power in Europe was not limited to the littorals of the English Channel and North Sea—the reigns of Louis XIV and XV saw many amphibious landings and naval bombardments around the continent—but this region had an outsized impact. England and Holland’s security concerns determined their place in the larger European alliance system: so long as Louis harbored designs on the Spanish Netherlands, those two powers were likely to support any coalition that opposed him on the continent. The Low Countries were therefore the link between land and sea competition in Europe.

Louis XIV: The Turn Toward and Away from the Sea

In the years following the Peace of Nijmegen, Louis pursued a dual policy of territorial annexation and naval expansion. Using questionable legal claims as a pretext, he absorbed neighboring towns in the Spanish Netherlands, Lorraine, and Alsace, including the major Rhine city of Strasbourg. These so-called “reunions” raised the hackles of other powers, and his blockade of Luxembourg in 1683 prompted Spain to declare war that October. Louis emerged triumphant from the War of the Reunions, adding Luxembourg to his existing gains the following summer. This success owed in no small part to the outbreak of a new war between Austria and the Turks; considering it inadvisable to make further aggressive moves against a Christian power busy against the infidels, Louis curbed his ambitions for a time and Europe remained at peace for the next few years.

Naval expansion was championed by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, one of Louis’ most formidable ministers. Colbert had come to prominence as a finance minister, helping to build the fiscal structure to support Louis’ expensive wars. He regularized the tax system, encouraged industry, and supported the founding of new colonies. The last of these required a strong navy, for which he was made responsible in 1669. Under his direction, the French navy grew to rival English and Dutch. When he died in September 1683, the fleet reached nearly 120 rated ships, including more than 70 ships-of-the-line.1 His son succeeded him as Secretary of State of the Navy and continued the buildup.

These twin developments on land and sea were met by parallel reactions in Europe. Spain, Austria, the United Provinces, and several smaller states of the Holy Roman Empire formed several defensive alliances among themselves in anticipation of future French aggression. Austria was making great strides against the Turks, and many expected Louis to strike while it was still distracted in the east. A dispute over the succession to the Archbishopric of Cologne in 1688 amplified these tensions.

The Dutch were meanwhile growing anxious over France’s rising naval strength, and feared that the new king of England, James II, would not honor his brother’s guarantees against the French. At the same time, discontent was rising against the monarch in England for his pro-Catholic and pro-French policies. Sensing an opportunity, the solidly Protestant William of Orange engineered an invitation by some English nobles to invade and overthrow his father-in-law. But before he could act, he had to be sure that Louis was not planning another offensive in the Low Countries—the French had been acting belligerently at sea, and had recently announced new trade restrictions against Holland.

Europe seemed headed for a major crisis, with the major powers coiled in unbearable tension. All eyes looked to Versailles, where Louis himself appeared undecided. Events in the east made up his mind: the Habsburgs captured Belgrade in September, and the Ottomans appeared on the verge of collapse. Louis decided to strike in the Rhineland while Austria was still distracted, to secure his favored candidate in Cologne and occupy a favorable position for future hostilities.

This was to be a quick war, along the lines of the Wars of Devolution or the Reunions—or, indeed, as he had originally intended the Dutch war to be—but several things conspired against him. William sensed his opportunity and set sail for England with a small army that November. Louis immediately declared war on Holland, but did not send any aid to Charles, expecting him to easily repel the invasion. Instead, James’ position rapidly deteriorated and Parliament declared William king in February. The deposed Stuart monarch fled to Ireland, leaving the Orangists to consolidate their position in England and Scotland. On mainland Europe, the Holy Roman Empire declared war that winter, compelling the German states to fight France. By spring 1689, the complex of alliances that had been forming against Louis went into action.

Nine Years’ War

The Nine Years’ War was fought in four major theaters along France’s borders: the Low Countries, the Rhineland, northwestern Italy, and Catalonia. Although Louis had not anticipated such a fierce reaction to what he saw as a limited action, the French war machine kicked into gear and mobilized several hundreds of thousands of soldiers, eventually reaching a notional strength of 400,000. His navy, already the strongest in Europe, continued to expand.

On land, Louis’ forces performed well throughout the war, winning one victory after another. Yet, like a lion attacked by hyenas, France could not land a knockout blow on any one front before being threatened on another; victory in one theater merely bought time to shuttle reinforcements to another, leaving no chance for exploitation. This problem was exacerbated by the cost of the navy, which competed with the army for the strained resources of the treasury. The navy was itself divided between the Brest fleet, which guarded the Channel, and the Toulon fleet, which defended the Mediterranean coast.

The Grand Alliance, which in 1690 expanded to include Spain and Savoy, was held together by the commercial wealth of Holland and especially England. William of Orange’s two realms provided subsidies to the Allies which allowed them to field armies year after year, slowly exhausting France despite her victories. Yet William was still vulnerable on his new throne. The deposed James II fought on in Ireland, to whom the Catholic population remained loyal. If he could conquer the Protestant towns of the north, he would have a secure base from which to invade England, where he still had many supporters. France’s best hope for a quick victory therefore lay in using sea power to support James in knocking England out of the war.

First Phase: Invasions of the British Isles

Louis himself recognized the opportunity. Throughout 1689 he sent convoys of troops and money to James, safely escorted by his warships. Yet here too he faced a dilemma. Victory in the British Isles ultimately required naval control, which required a general fleet action. At the same time, William was sending reinforcements of his own to Ireland, imperiling James’ position there. The fleet could not adequately concentrate against the Allies while also interdicting Orangist reinforcements crossing the Irish Sea; forced to choose, Louis opted for the latter.

In summer 1690, the Toulon squadron sailed to Brest, forming a combined fleet of 70 ships-of-the-line, 8 frigates, and 22 fireships. This set off under Vice-Admiral Tourville in search of the Anglo-Dutch fleet, which it found on 10 July off a place called Beachy Head on the Sussex coast. Although the Allies had only 56 ships in their line, they gave battle. The result of the day-long engagement was a French victory: the English and Dutch lost or were forced to scuttle 8 ships and several smaller ones, against no losses for the French. Tourville ordered a deliberate pursuit the next day, maintaining good order, but this was too slow to catch up and the Allied fleet got away.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.