Notes on Annihilation

Perhaps no battle in history has witnessed so complete an annihilation of an army as the Battle of Hattin. As many as 70,000 men took the field on 4 July 1187: about 23,000 Crusaders against roughly twice as many for Saladin’s army. By evening, the Army of Jerusalem was utterly vanquished. Almost all who were not killed were captured, with no more than a few hundred escaping the battlefield. One eyewitness said that 200 of the Christians escaped at most—less than 1% of the entire army. Not Cannae, not Teutoburg Forest, not the great encirclement battles of World War II come close to the thoroughness of the destruction.

The defeat was all the greater for the fact that the army constituted nearly the entire military strength of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Every able-bodied man that could be spared was mobilized, plus reinforcements from neighboring states and abroad. Only a few pitiful garrisons were left to defend the major cities and castles of the realm, almost all of which fell to Saladin’s army in the following months. This included Jerusalem itself, which surrendered exactly 3 months after Hattin in a brave but futile defense.

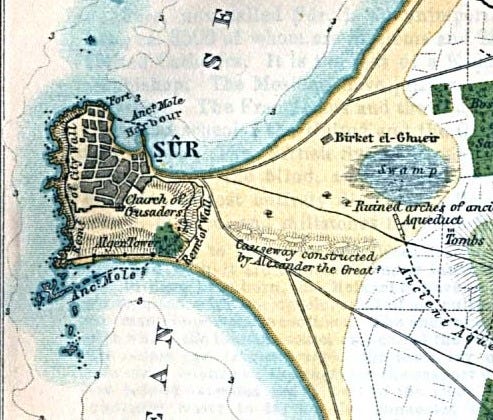

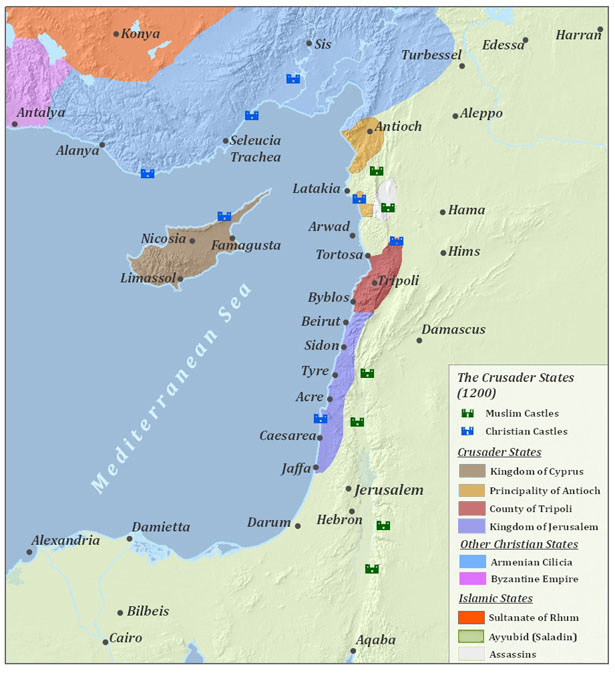

And yet Hattin did not mark the extinction of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. One vital place held out, the supremely defensible Tyre—the city that was once an island, until Alexander the Great constructed a causeway from the mainland during his 332 BC siege. The remnants of the shattered army and neighboring garrisons took refuge within the city, soon strengthened by fresh arrivals from overseas. By the time Saladin arrived before its walls, the defenders’ confidence had been restored, and he was unable to take the city before the winter rains set in.

More reinforcements flowed into Tyre over the following years, a beachhead by which the Christians recovered much of their territory—by 1198, they had secured over 200 km of the coast, from Beirut to Jaffa. Although the Kingdom of Jerusalem’s territory was much diminished and its fighting strength had been permanently injured, it would last another century before its final fall.

Annihilation and Victory

How is it that Hattin, which is more justly described by the term “annihilation” than any other, did not result in a total victory for Saladin, whereas far less destructive battles have ended empires? The answer lies in the definition of destruction itself. While some doctrinal definitions assign the term precise percentages of enemy forces destroyed, most are more qualitative—the US military gives it as rendering a force combat ineffective unless reconstituted.

Unless reconstituted is the key phrase. Any determined adversary will immediately begin to rebuild his forces given the chance—or, indeed, before the most destructive battles have even taken place. By the end of 1942, the Soviet Union had suffered well over 6 million irrecoverable losses, more than the entire mobilized force at the start of the war. Yet by that point in the war, they had nearly twice that number under arms.

Compare that to Austerlitz, a far less destructive battle in absolute or relative terms. Of the ~75,000 Austrian and Russian soldiers engaged, some 30-50% were casualties (against more than 10% for Napoleon’s somewhat smaller army). This by itself was not an irreversible defeat: there existed the possibility of reinforcement from other soldiers in theater, from the nearly 100,000 Austrians in Italy, and from a possible entry of Prussia into the war. What made this battle decisive was a crucial fact not mentioned in most accounts: the capture of the Allies’ baggage train. Without it, the Austrian and Russian emperors could not hold their army together long enough in the face of Napoleon’s pursuit to recover and reconstitute.

Clausewitz’ exhortation to focus on the enemy’s destruction is therefore only half the formula for victory; the other is to exploit that destruction to prevent force regeneration. This cannot usually be done in a single battle as at Austerlitz, and there are rarely any shortcuts—more often, it entails the capture of political centers, occupation of territory, destruction of armaments, etc. In Saladin’s case, it would have entailed reducing every port through which reinforcements arrived. The difference between attrition and other forms of warfare does not lie in total quantity of destruction, after all, but in the exploitation of those brief windows of opportunity.

For more on the Battle of Hattin and the campaigns leading up to it, check out Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Subscribers to the Bazaar of War also receive access to more in-depth articles on many historical subjects, including several on the warfare of that period.