Attrition and Its Opposites: A Rectification of Names

It is no longer so fashionable to speak of maneuver and attrition as two poles of a spectrum. It is often pointed out how the two complement each other, how the paradigm falsely contrasts actions at different levels of war, and so forth. Yet the most pertinent criticism is that placing maneuver and attrition at opposite ends of a single spectrum is a category error, a comparison of two unlike things.

The older habit was to contrast attrition with destruction, following Clausewitz’ terminology. Destruction in a literal sense is just attrition over a short timeframe, but its value does not lie in the total damage it inflicts; rather, it is in the window of opportunity it opens. A beaten army in disarray is unable to block the road to the capital or otherwise interfere with the adversary, even if it still maintains reasonable strength on paper.

Literal destruction is not always necessary to accomplish this, which may be done equally well through brilliant and costless maneuvers. What really matters is the time gained for exploitation, as inseparable a part of victory as any actions on the battlefield. The defining quality of attrition, by contrast, is that there is no room for exploitation: the enemy is able to reconstitute after every setback, continuing to resist from a marginally weaker position.

The opposite of attrition is neither maneuver nor destruction, but decision.

The Spectrum

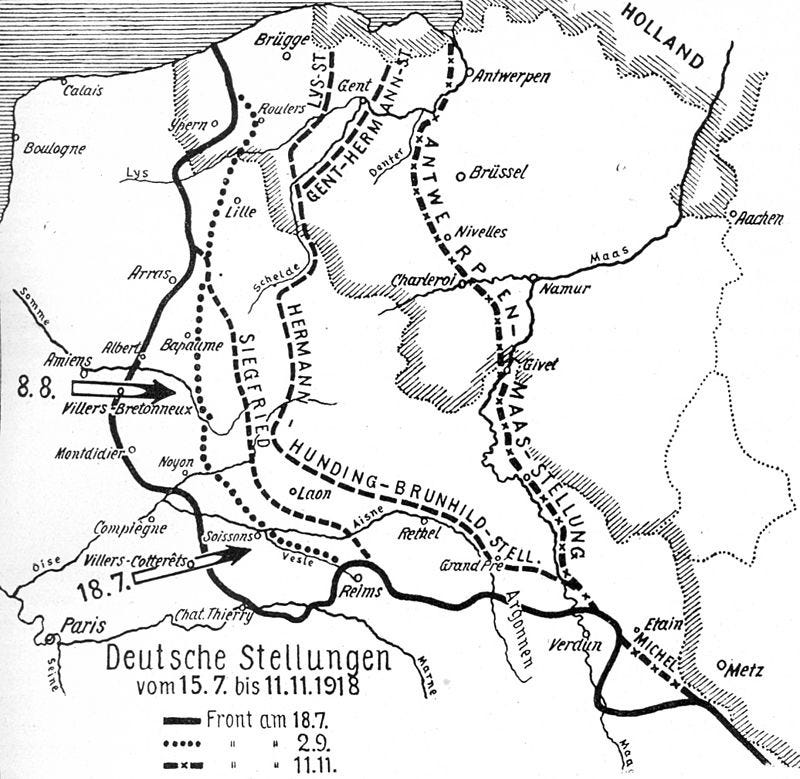

It could be reasonably objected that attrition is merely the prelude to decision, the softening-up before the coup de grâce. This describes many wars—the European theater of World War II, the War of the Sixth Coalition, the Gulf War—in which one side is steadily weakened as the other advances, up to the pitiful last stand. Yet the final blow in wars of attrition is rarely decisive in its own right. The Hundred Days Campaign convinced the Germans that they had lost World War I, but did not immediately threaten their borders. Two atomic bombs persuaded Japan to surrender, even if they did not really change the underlying situation. The timing of both was a question of will, of the losing sides coming to terms with their inevitable defeat, even though they maintained the potential to inflict enormous losses on the victors.

These are extreme examples in which the losers suffered total defeat. Far more frequently, a strategy of attrition depletes both sides’ offensive capability, leaving one side the winner in only a relative sense. Up until the French Revolution, this was the rule for large-scale European warfare. Offensive campaigns were launched annually until both sides were exhausted, after which occupied lands were signed away or traded for concessions elsewhere in negotiations that reflected the relative military balance. Nor is this unheard of in the modern era: the Korean War ended largely along the lines at which it began, while neither Russia nor Ukraine have managed to make any substantial gains for an entire year—production bottlenecks raise the question of whether any large power could win a major war outright.

True decision, by contrast, takes the timing of defeat out of the hands of defeated—cities and lands are occupied no matter how stubborn the remaining resistance. France’s surrender in 1940 was not a collapse of will, but the mere acknowledgement of reality. Although the country was in no sense exhausted—given enough time, it could have raised new troops and churned out more tanks—the government was at that moment incapable of preventing an occupation.

Leaning into the Advantage

Attrition and decision are defined by how they achieve victory, so the nature of a conflict is never fully settled until after the fact. A decisive campaign might take over a year to produce results, while rapid gains may prove no more consequential than the losses they impose. Settling on an appropriate war strategy—fundamentally a question of economy of force—therefore requires remarkable clarity of vision and steadiness of spirit to perceive the true lay of the land. The allure of rapid decision can easily lead one astray, and political necessity often compels a focus on the wrong objectives even when the right type of strategy is decided.

Svechin, with the benefit of hindsight, offered the following criticism of Allied campaign planning in World War I:

As soon as the center of gravity of German activity had shifted to the Russian front in 1915, Great Britain and France should have done everything possible permitted by their communications on the Balkan front to support Serbia; the deployment of a 500,000-man Anglo-French army on the Danube would have forced Bulgaria to stay neutral, encouraged Romania to act, cut off any German communications with Turkey, made it possible for the Italians to come out through the border mountains, would have relieved the strain on the Russian front, which could have held in Poland, and would have greatly accelerated the collapse of Austria-Hungary.1

In short, the Allies were too fixated on the politically important Western Front. This prevented them from effectively deploying their advantage in overall strength and compelled them to attack where the Central Powers were they strongest, against high ground held by some of the best units in the German Army. Thus, not only did they fail to secure any advantage in 1915, but they allowed their adversaries to improve the balance by winning over Bulgaria to their side—considerations not so apparent less than a year after the Great Retreat.

The Reverse Side of the Coin

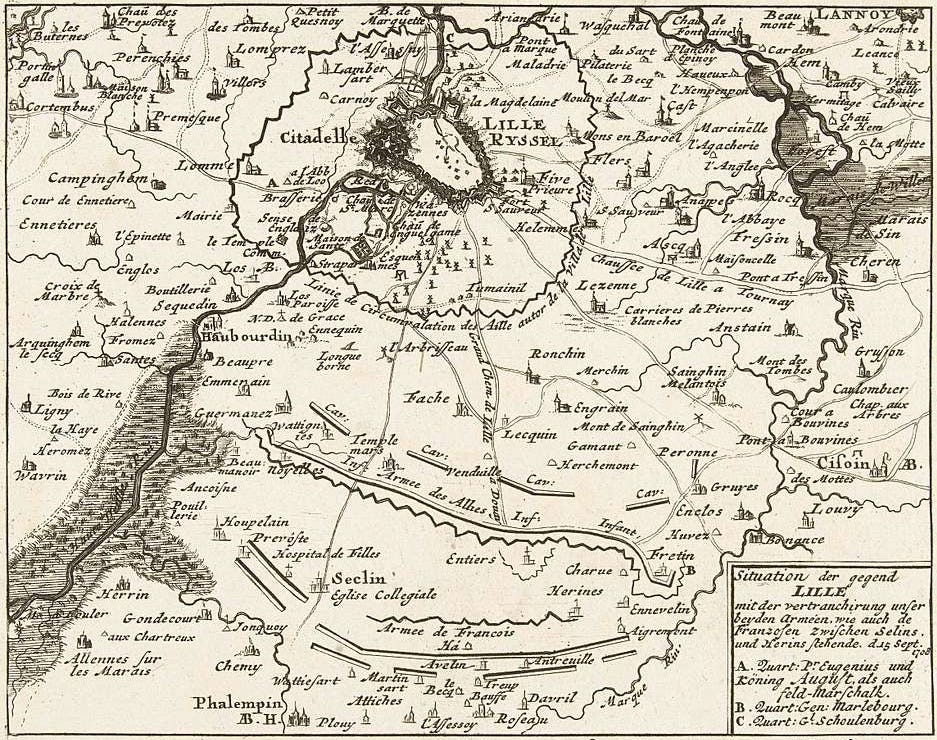

Whatever course an attacker takes, it often makes sense for the defender to take the opposite. Offensive power is extremely perishable in high-intensity combat, so this frequently means embracing attrition. In such cases, certain battles are almost decisive by virtue of the non-decision they produce. The Russians lost at Borodino in 1812 and the French at Malplaquet in 1709, yet by withdrawing with their armies intact, both left their enemies on the wrong side of an attritional war. Similarly, the Soviet victories at Moscow and Stalingrad and French victory at the Marne were far more significant for what they denied the Germans than for any losses they inflicted.

Successful attrition presupposes on overall advantage on the part of the defender. If the attacker embraces attrition, however, or if he readily has the means to, then the defender’s best hope may well lie in gambling on a series of sharp victories. Yet that also means the attacker has such an advantage to begin that the odds are bound to be desperate—Frederick the Great’s experience in the Seven Years’ War and Lee’s in the American Civil War demonstrate just how difficult it can be to land a knockout blow.

The Allies in 1916, having learned from their failures the previous year, showed how easily this strategy could be countered: by launching simultaneous offensives in three different theaters, they prevented the Central Powers from concentrating enough at any one point to achieve a local decision, leading to the defeat of Germany’s great push at Verdun.

The Interaction Between Levels

The question becomes even more vexed where strategy interacts with the lower levels of warfare. Whereas both the Western Front of WWI and Eastern Front of WWII were largely attritional, the latter saw plenty of decisive combat at the operational and tactical levels—entire armies were destroyed as vast territories changed hands. This is more the rule than the exception for attritional wars: diminishing the enemy’s overall strength makes it easier to achieve local decisions, which then feeds back into higher-level attrition; as the snowball gains momentum, lower-level victories take on increasing strategic importance. By 1944 the Red Army succeeded in smashing Army Group Center with Operation Bagration, eliminating a large part of remaining German combat power and pushing the front back several hundred kilometers.

This means that even at lower levels, there is no escape from the dilemma between narrow operations that preserve favorable loss ratios and striving for wider gains. Getting this wrong can undermine even a good strategy. The “proper” balance is highly contingent on technology, existing doctrine, the enemy, and countless other factors, all of which interact in unpredictable ways. WWI generals eventually learned to employ bite-and-hold tactics that achieved extremely limited decisions—no more than one trenchline at a time—a technique which nevertheless required extensive training to execute. Soviet counterattacks during the first year of Barbarossa, on the other hand, could sometimes destroy entire German divisions, but suffered catastrophically against larger formations; as the war progressed, they managed to encircle entire armies and army groups. In both cases, figuring out the best means to execute a basically sound strategy exacted staggering tolls.

The reverse pattern, using local attrition to achieve higher-level decision, requires much more coordination. A weakened defender can usually be reinforced from another area, requiring them to be isolated in order to achieve any results—by a covering force for a siege, for instance, or the sea blockade of an entire theater. Alternatively, pressure can be exerted at multiple locations to prevent reinforcements from being shifted, in the hope that one or more sectors will give way (in essence how the Hindenburg Line was breached in October 1918).

Attrition can last indefinitely, however, which runs counter to most schemes of decision. If the isolation or pressure cannot be maintained, then any losses inflicted are only useful insofar as they contribute to the aggregate. If the attacker has only a narrow window for victory, then delay can be fatal—consider how much of the Wehrmacht’s strength was absorbed by the siege of Leningrad.

Blind Strategists

This complex interaction of attrition and decision makes up a large part of the inherent uncertainty of war. It plays havoc with assumptions and precludes an “optimal” path. Strategy cannot be wedded to one particular theory of victory, but must seek out any kind of advantage that allows for further action: to capture the nearest peak and see what lies beyond. Every move, every operation is just as much an experiment as it is a bid for success—this leads us by other means back to algorithmic warfare, the subject of last post. The greatest challenge of all lies in perceiving what one is facing and acting accordingly.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Strategy, p. 246

Thank you for this article!

Excellent