Algorithmic Warfare and Strategic Patience

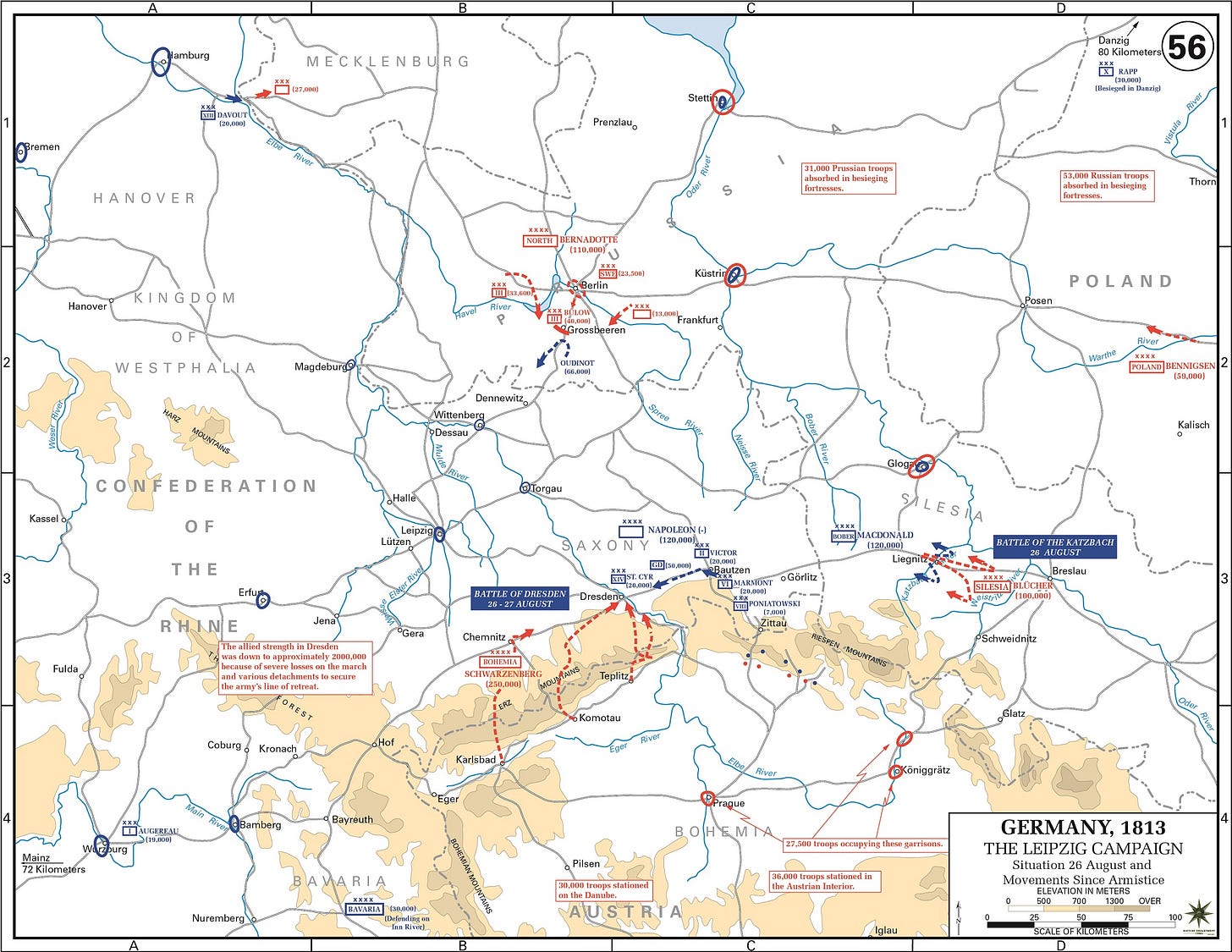

On 12 July 1813, representatives from Austria, Prussia, Sweden, and Russia met at Trachenberg Palace in western Poland to plan the upcoming campaign against Napoleon. The Emperor of the French had been driven from Russia the previous winter, encouraging Sweden and Prussia to join the Sixth Coalition. Austria was expected to follow in the autumn, giving the Allies a strong advantage.

Nevertheless, Napoleon remained a potent threat. He had gathered reinforcements in eastern Germany and occupied a strong position along a nearly two-hundred-mile front. His genius in battle was undiminished, capable of reliably pulling out a victory when evenly matched; and while the Allies of the Sixth Coalition had the numbers to simply overpower him, they had to corner him first—unfortunately, Napoleon had a preternatural talent for appearing at the right place and right time to preempt any concentration of forces.

The Allies’ campaign plan, known as the Trachenberg Convention, was designed to counter these strengths. The plan was simple: three armies were to advance against the French from the north, east, and south. Whenever they had a local advantage, they would attack; whenever Napoleon was present in person and could choose the ground of battle, they would withdraw to safety. The noose would draw tighter around the French until the Allies could concentrate all their forces against Napoleon himself.

The plan worked exactly as intended. The Allies advanced relentlessly, mostly avoiding Napoleon while inflicting continual defeats on the French.1 The Emperor futilely scrambled from one side of the front to the other, but could never secure more than minor, unsatisfying victories. By 16 October the Allies converged on him at Leipzig, and in the largest and bloodiest battle of the Napoleonic Wars, he suffered a crippling defeat that led directly to his downfall six months later.

Algorithmic Warfare

What makes the Trachenberg Convention remarkable is that it was a simple algorithm, a set of recursive instructions in the place of a fixed operational objective. This solved several problems at once. It allowed armies separated by hundreds of miles to coordinate their actions without central direction; it negated Napoleon’s strengths as a general, frustrating any attempts to win through a series of quick victories; and it developed the situation in the Allies’ favor, to where they could risk a decisive engagement.

Operational algorithms are nothing new in warfare. They practically define small wars and insurgencies, where they allow coordination among dispersed cells. Insurgent leaders often issue guidelines to their subordinates, including codes of conduct to win over the civilian populace and conditions for when to attack and retreat. Groups share tactics and techniques among themselves, seeing what works and tweaking the algorithm as they go. Counterinsurgencies act in a similar manner, giving small units broad autonomy under a defined set of rules.

These sorts of protocols are much rarer in high-intensity warfare. Modern communications solve the problem of coordination, and careful synchronization of efforts towards specific objectives is far more effective than open-ended parallel efforts. Only at the small-unit level on the defense, which is inherently reactive, does it appear to any great extent.

One notable exception on the offense is the air campaign during Second Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijan employed flights of UAVs consisting of decoys to trigger air defenses, followed by armed drones to destroy those systems; whenever air defenses did not respond, they struck ground targets of opportunity instead. This was just one part of a larger campaign, but a crucial one: it enabled an eventual breakthrough by ground forces that won the war for Azerbaijan.

Second Nagorno-Karabakh was unique in many ways, small in scale yet incorporating

Yet three major trends are converging to make this sort of pattern more likely on a larger scale:

-the unavoidability of a long initial attritional phase

-centralization of command-and-control

-accelerating technical and technological innovation

1. The Attritional Phase

Modern standoff weapons pose a dilemma for all but the strongest of attackers. Unless one side has complete overmatch, it is a sore temptation to gamble on a fast ground campaign to avoid getting bogged down in a costly slog—at the obvious risk of leaving oneself worse off for the attritional fight (more on that here). The alternative is to lean into attrition, wearing down the enemy at the least possible cost before attempting anything decisive.

Azerbaijan tried to thread this needle by launching its air campaign in parallel with a ground offensive. It had a marked advantage in number and quality of drones, but probably lacked sufficient numbers to completely degrade Armenian forces outright; delaying would have moreover given the Armenians time to adapt to their novel tactics. Ground forces made several false starts, shifting their focus of effort multiple times before managing to capture Shusha and thereby win the war.

This was more trial-and-error than algorithmic, but suggests a method for conducting ground offensives according to a coherent set of rules that maximize attritional advantage. In an advance on multiple close axes, immediate objectives could be assigned according to level of resistance. These would be revisited daily, weekly, or longer depending on the size of tactical units involved, with force ratios reevaluated at each step. Air, EW, and long-range artillery would be reallocated accordingly, and over longer timeframes ground units could be reassigned as well.

By continually flowing to the path of least resistance, the front commander would not be trying to break through so much as deplete the defender’s strength—part of a larger attritional effort. Only once certain conditions were met would he attempt a decisive action.

2. Centralization of C2

Unlike the rules governing insurgent cells or the Sixth Coalition, this describes a highly centralized approach. The operational algorithm gives complex rules for how to employ all forces, not simple rules for each subordinate command. Managing this depends on good intelligence and careful analytical work, which in turn depends on the integration of all incoming data across the front.

A previous piece explored how pervasive UAV coverage and other means of surveillance often gives higher-level headquarters better situational awareness than anyone on the ground. A corollary is that this allows HHQ to precisely gauge the effectiveness of each attack, tailoring the means and objectives to optimize overall performance across the front.

3. Accelerating innovation

Planning any operation requires a reasonable estimate of the effectiveness of the tactical tools used to carry it out. Accelerating technological change makes this very difficult to predict. Even when new weapons technologies are not complete gamechangers in themselves, they breed new techniques and are used in combination with other systems in unique combinations, compounding the rate of change. As a result, fighting styles often become completely unrecognizable by the end of a war.

This unfortunately makes the learning curve very steep as human intuition can’t keep up. As disastrous armor attacks in Zaporizhzhia by both Russians and Ukrainians attest, there is a strong temptation to gamble on all-out pushes for even limited objectives. These calculations change when the goal is not to create a breach, but simply to wear down the enemy. Every encounter becomes a data point that feeds back into the operational algorithm to refine one’s assessment of relative odds of success in a given situation.2

Strategic Patience

This speaks to the broader problem of embracing attrition. There is strong psychological pressure to pursue a decisive victory, especially early on. Political leaders do not like to be told that the expense will last indefinitely, and popular enthusiasm does not last forever; troop morale usually requires solid victories, and conducting a campaign without definite operational objectives goes against every instinct of a general staff. Excepting those cases when the attacker is completely dominant, as the US was during Desert Storm, embracing attrition from the get-go requires extraordinary strategic patience.

We see this time and again throughout history. The vast open plains of Russia were ideal for drawing in Napoleon and wearing his forces down, but national pride demanded several set-piece battles, including the bloody Battle of Borodino. Stalin likewise ordered many disastrous counterattacks during Operation Barbarossa which cost him far more than the Germans. By 1916 the Entente had openly embraced a strategy of attrition against Germany, yet even then held out hope for a breakthrough with the Somme Offensive. No matter how capable commanders are of forming rational assessments, the strain of war can skew their judgments.

The word “algorithm” calls to mind computers and AI, something cold and mechanistic. Although these tools can no doubt play an important role in making sense of the swamp of information from the modern battlefield, the essence of an operational algorithm is altogether more human. It lies in the discipline it imposes on a commander and his staff, the strict rules that ensure they will stay true to the logic of the situation—it is a means of enforcing strategic patience.

There is no eliminating the role of human judgment in war. The decision to go to war is itself a question of judgment, and its conduct is guided by far more than strictly military considerations. Operational algorithms can never replace the human element, but they might be able to help commanders avoid the worst of their own errors.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

The one exception was the Battle of Dresden, where Napoleon defeated a large Austrian army under Schwarzenberg, his last major victory. The Allies would not repeat their mistake.

It is entirely possible that Ukraine’s much slower pace since the early weeks of the 2023 counteroffensive reflect a more conditions-based approach to their broad-front strategy.

A superb display of a broad base of (historical) knowledge, and a mind sharpened for synthesis—I applaud you in possessing this rare combination. Great article.

That's a hugely comprehensive article, thank you.