Last piece looked at conflicts that get entangled with one another, metastasizing into sprawling coalitionary wars fought in multiple theaters. The common element is diverging strategic objectives: when allies are fighting for separate war aims, they have the tendency to prolong and intensify the conflict. So too when a single power fights for separate strategic objectives in different theaters, as the Americans did against the Germans and Japanese and as the British did in various colonial struggles during the Seven Years’ War. Efforts in one theater necessarily come at the expense of the other, requiring the enlistment of local allies while delaying victory.

Although often a political necessity, this violates basic strategic wisdom. Ideally, different fronts or theaters complement one another, following the same logic as combined arms at the tactical level or supporting lines of effort at the operational.

The particular mechanism of support can vary. Most common is for operations in two theaters to aim at the same objective: if faced with deadlock on one front, it might still be possible to make progress on another (often shifting forces rapidly to create a breakthrough). This two-theater strategy characterized France’s wars with Austria across the centuries. Lacking a direct border with their heartlands, they had to invade through southern Germany, northern Italy, or both. Napoleon’s Italian victories of 1796 and 1800 were supported by parallel campaigns along the Danube, and vice-versa for his campaigns of 1805 and 1809.

This is also done by coalition partners. The Allies in both World Wars attacked Germany from east and west, with the intent of either breaking through or at least drawing forces away from the opposite front; Egypt and Syria attempted the same against Israel. In all such cases, there is an essential equality between the two theaters, and it is only an accident of circumstance which (if any) ends up reaching the strategic objective first.

Economy of Force

Other times, however, a theater is decidedly auxiliary to the main effort. The Soviet conquest of Romania is one such example. This opened up an alternative route into Germany in the event that Soviet progress got stalled along the Vistula, but far more importantly it knocked a German ally out of the war and captured a large portion of their oil supply. Its effects were therefore attritional: it aided the main effort insofar as it reduced overall Axis strength.

The Anglo-American strategic bombing campaign functioned the same way. Even in 1942 and ’43, before the effects of the bombing began to show, it allowed the western Allies to apply their superior industrial might in some way in advance of a ground campaign.

Similarly, it was very common in the 18th century to send armies into enemy territory along quiet fronts, even when there was no immediate objective. This was a cost-saving measure—they could feed and quarter their own troops at the enemy’s expense—and it often forced him to commit troops from elsewhere to contain these incursions. Most wars of the period ended when they became too expensive for one side to sustain, making this an effective use of attrition.

The African Campaigns

This may be a viable strategy for the stronger side in a war, but what about the weaker? Without some other, overriding objective at stake, there is no reason to engage at all in secondary theaters, unless it can achieve a very favorable economy of force. Germany’s campaigns in Africa in both World Wars provide an interesting lens to look at this problem. In both cases, Germany and her allies were facing much stronger coalitions in Europe, and anything that could be accomplished in Africa was decidedly peripheral to the outcome.

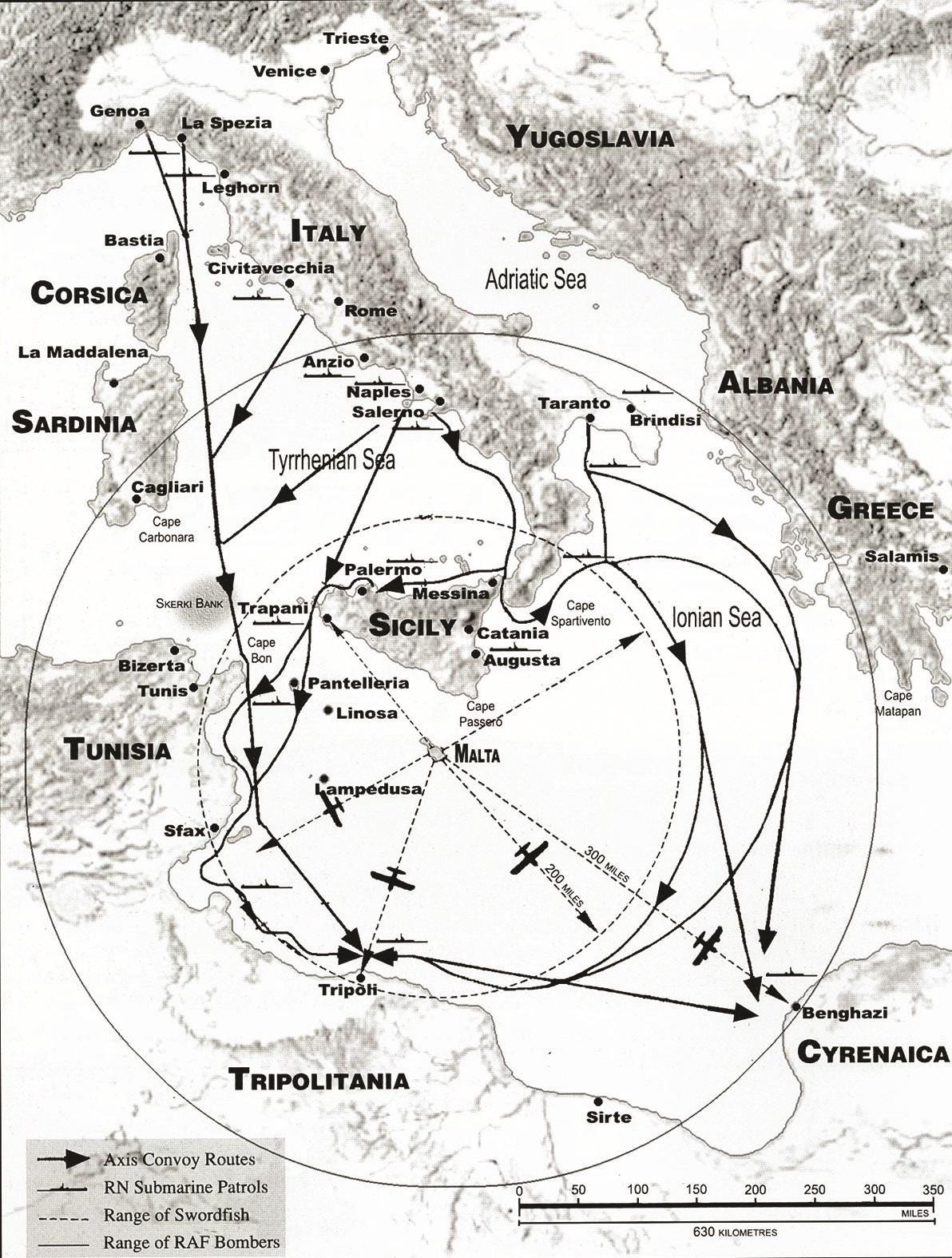

The North African theater of World War II is the more famous of these. The initial German deployment was only two divisions—barely 1% of what invaded the USSR that same year—although Italian forces were much more numerous, and more German reinforcements arrived later in the campaign. More critically, this was supported by a full fighter wing and resupplied along the exposed Mediterranean route.

Axis objectives in North Africa were nevertheless complicated. For Mussolini, this was a primary theater, one in which to reassert Italy’s ancient dominance over the Mediterranean. Things were less clear for the Germans. On the one hand, they wanted to aid their Italian allies in order to keep them in the war. In this sense, North Africa was a classic example of a Siamese conflict: a strategic burden they had to bear to maintain the strength of their coalition, like the subsidies France and Britain paid to their German allies in the 18th century.

Germany also had more immediate reasons to be interested in North Africa. In the first place, there was the sensible precaution of denying its use to the Allies as a launch pad to invade southern Europe—this by-and-large complemented the objective of supporting Italy. Yet Rommel was altogether more ambitious: he hoped to drive the British out of Egypt, perhaps even continuing on to take their Middle Eastern oil fields.

Competing strategic objectives are much like competing theaters: efforts toward one draw away from the other. Rommel’s dash toward the Nile diverted resources from a planned invasion of Malta in the summer of 1942, leaving British aircraft and submarines free to operate in the central Mediterranean. This left Axis lines of communication exposed, even as their ground forces strained their logistical apparatus to the utmost. In the months between the two battles of Alamein, losses of supplies crossing the Mediterranean exceeded 20%, compounded by the cumulative loss in ships; to make matters worse, British air raids shut down the port of Tobruk on the eve of Second Alamein, leaving Rommel critically undersupplied for the campaign’s culminating battle.

The Axis withdrew from Egypt a spent force, lacking the combat power and supplies to head off either the advancing British Eighth Army or the Anglo-American forces then landing in Morocco. This was the worst of all worlds for the Germans: unable to accomplish their maximal objectives (which were always probably out of reach), their offensive left them on the wrong side of the economy-of-force ratio. On land, air, and sea, the balance favored the Allies. When Axis forces in Africa finally surrendered in May 1943, nearly 300,000 soldiers were captured with most of their equipment, leaving the invasion route to Italy open.

German East Africa

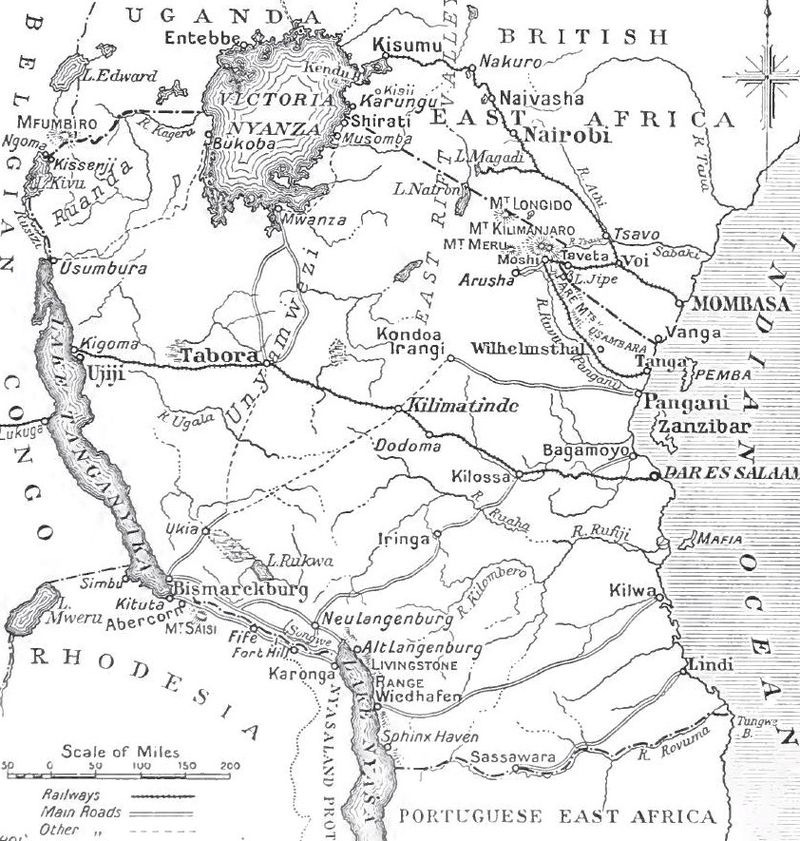

The difference could not have been greater with Germany’s African experience during the First World War. The principal theater was not North Africa, but the German East African territory comprising modern Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi. It was defended by the Schutztruppe, the colonial troops, composed of fewer than 3000 Europeans and Africans, and which was oriented more towards suppressing local rebellions than fighting a peer conflict.

Nor was there any question of resupply or reinforcement. The Royal Navy was at the height of its power, and as soon as war was declared it was able to completely isolate the colony by sea. The only relief was from a single cruiser which had managed to evade the initial blockade and harry shipping in the Indian Ocean before holing up in the Rufiji Delta. After tying down a sizable British covering squadron for several months, it was scuttled and its guns dismounted to serve as artillery for the Schutztruppe.

The biggest question was whether to fight at all. The governor of German East Africa wanted to protect German homesteads by assuring the British he would not cause trouble. The commander of the Schutztruppe, Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, was not part of the colonial gentry and had sworn an oath to the Kaiser: he saw it as his duty to support the Fatherland in any way possible. Lettow-Vorbeck ultimately won out and began expanding the Schutztruppe, recruiting German settlers and native Africans to bring its eventual strength to over 15,000.

This took time, however, and in the meantime the British were mobilizing an expeditionary force in India. Lettow-Vorbeck’s initial concept of operations was similar to Rommel’s in its boldness. After defeating an attempted landing at the northern port of Tanga, in which the Germans were outnumbered almost 10-to-1 yet inflicted nearly 50% casualties, he set up base around Mount Kilimanjaro on the border with British East Africa (Kenya). From there he launched raids on the rail line that connected the coast to the interior.

Lettow-Vorbeck never had any hope of overrunning the enemy—his troops were too few, too poorly equipped, and the British had access to manpower both from India and its other African colonies. Yet it was not until 1916 that the Allies managed to invade German East Africa: the British from the northeast, a combined British-Belgian force from the Belgian Congo to the northwest. Schutztruppe elements fought a series of delaying actions, withdrawing along the rail lines, before cutting loose entirely and marching cross-country.

The dense bush, combined with horses’ susceptibility to tropical diseases, forced both armies to rely on huge numbers of porters to carry their supplies, and movement was effectively halted for months at a stretch during monsoon season. Disease took a heavy toll on both sides, but the more numerous and less-acclimatized Allies suffered far worse. Nevertheless, they managed to overrun all of German East Africa after a campaign of nearly two years. The Schutztruppe fled into Portuguese Mozambique in late 1917 and spent the final year of the war eluding capture there and in Rhodesia, finally surrendering on 25 November 1918 after being informed of the Armistice.

Lettow-Vorbeck managed to keep his forces intact for the entirety of the war, tying down hundreds of thousands of Allied troops. Only some of these would have otherwise been sent to the Western Front, but their employment was very expensive and occupied disproportionate attention from the Allies’ central governments. The Germans, by contrast, had been cut off from radio contact with Berlin cut since early 1916 and sustained themselves entirely off the colony’s resources.

Warfare by Balance Sheet

No matter how impressive Lettow-Vorbeck’s achievement, his greatest efforts could not win the war for Germany, just as an improbable victory by Rommel would not have changed the course of WWII. It is only by looking at their contributions to the aggregate balance that we can judge their true contributions to the war. By this standard, Lettow-Vorbeck was far the more successful (acknowledging that his choices were greatly simplified by a lack of alternatives).

Following the same logic, it is hardly surprising that Ukrainian special forces have attacked Wagner in Africa while stepping up cross-border incursions into Russia: facing an unfavorable balance of forces on the main front, they are trying to even the balance elsewhere. Generalizing this phenomenon to the types of entangled conflicts discussed in last piece, economy-of-force operations in secondary theaters are like proxy wars. They rarely accomplish strategic objectives in their own right, but make marginal contributions to the larger conflict.

Once started, however, they are carried forth by their own momentum, subject to their own dynamics. It is not always so easy to extract forces from a secondary theater once the loss ratio turns unfavorable, as the Germans surrendering in Tunisia were dismayed to learn.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Please like and share if you enjoyed, it helps more people find this. You can also support with a paid subscription, supporters receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529 and get access to exclusive pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.

Actually there were two relief ships that got through to German East Africa in the Great War and a supply Zeppelin was sent late in the war from Bulgaria that was specially designed to be completely reused. (It was suppose to be a one way trip.) It turned back receiving what is believed to be a false message. Lettow Vorbeck was a master of various forms of warfare moving from conventional to guerilla warfare as the situation required. He tied down some 300k Allied troops not to mention the support resources with a force that maxed out at 15K early on, but for support purposes functioned with 4000-1500 most of the time…

British subsidies to German land armies; In any land war prior to the completely ruinous and counterproductive to the British Empire World wars of the 20th century, the Germans were often enough the main land effort if not THE main effort on land. I refer to Marlborough, Frederick in the Seven Years War, Blucher at Waterloo… France a different matter, but the British were ruined by land armies against Germany in the World Wars, and the Cold War Army of the Rhine wasn’t cheap either.

“strategic burden they had to bear to maintain the strength of their coalition, like the subsidies France and Britain paid to their German allies in the 18th century.”