Strategy in an Endless War: The Arab-Byzantine Frontier, Part 1

One of the most compelling points in Wayne Lee’s The Cutting-Off Way was the strategic logic of Native American warfare. For societies with low population densities which depended on hunting for subsistence, it was simply not possible to conquer and occupy territory. Tribal territory, such as it was, consisted of vast hunting grounds that made possession a much vaguer concept, and men could not be spared for fortress garrisons which would render it more concrete.

Strategy, as a Westerner would understand it, instead consisted of series of regular raids designed to compel capitulation: to force the enemy tribe to pay tribute, make some more symbolic performance of obeisance, or abandon their hunting grounds altogether.

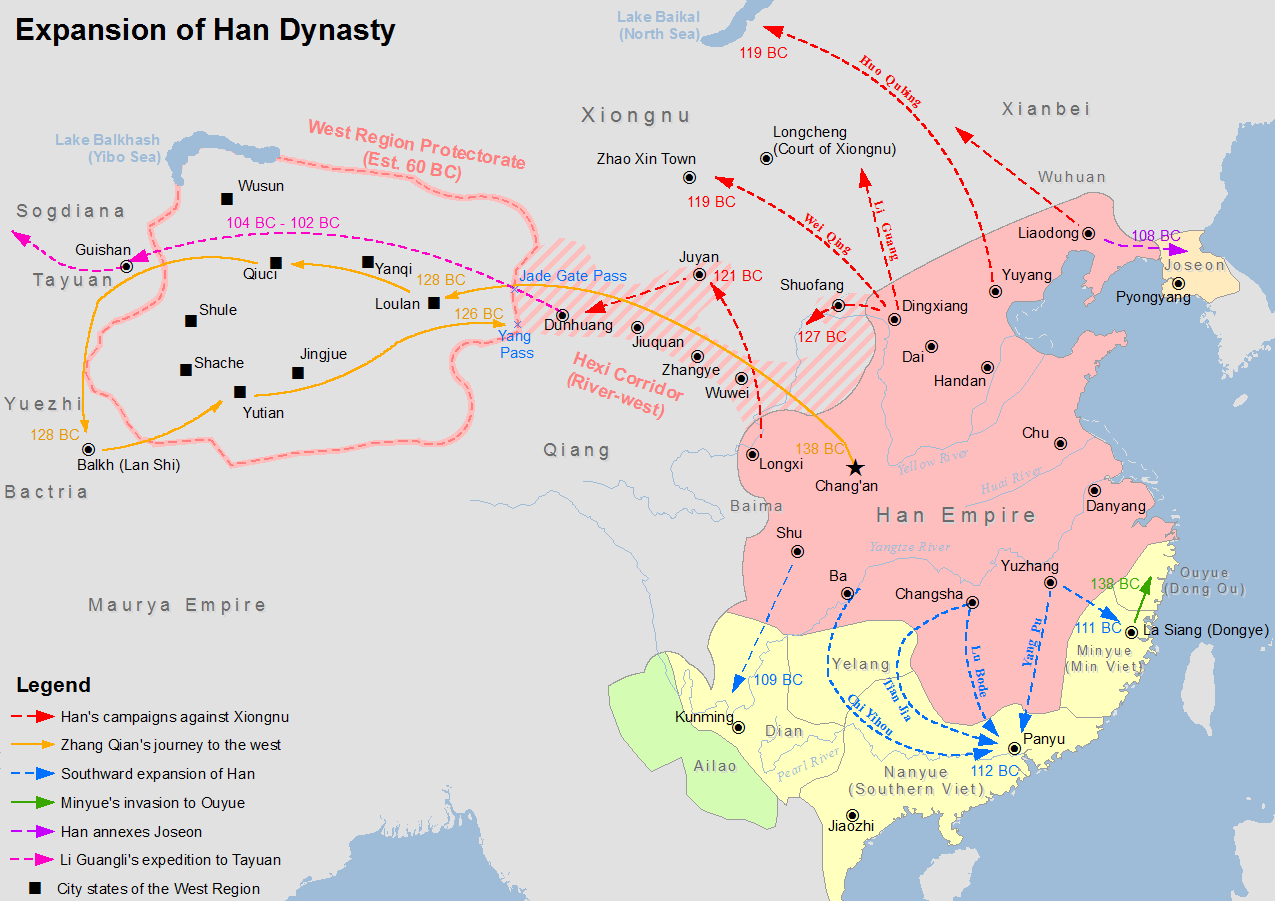

There is an obvious comparison to the endemic warfare that existed among nomadic tribes of the Eurasian steppe, which can be extended to their relations with sedentary neighbors—Imperial China, Russia, and Persia all come to mind. The nomads followed a similar strategy: through constant raiding, they could gain pastureland by forcing their neighbors to abandon their farms along the border, or force the imperial capital to pay tribute in return for peace. Only in very rare cases such as the Mongols could they subdue a state outright; and even, their campaigns of conquest were preceded by years of regular raids.

But similar dynamics also existed between sedentary societies. Premodern empires often existed in a semi-permanent state of war with their neighbors: low-grade raiding and counterraiding by border troops, punctuated by occasional large-scale operations or truces. Although territory could and did change hands, there was far less chance of a catastrophic defeat or victory between powers of sufficient size.

Such was the state of affairs that existed between Byzantium and various Arab powers for over 300 years. From the time of the first Islamic conquests until the Byzantines finally pacified the border area in the 10th century, warfare predominantly consisted of raids on an occasionally enormous scale. The intensity of the fighting ebbed and flowed, punctuated by occasional truces, but any peace was only temporary; for the better part of those three centuries, war was the rule, not the exception.

Strategy on an Open Frontier

This raises the question of how political leaders viewed strategy in these wars. This is not as obvious as it might seem. The Arabs’ ultimate aim was nothing short of Constantinople itself. The magnificent capital of the Roman Empire’s eastern remnant held a particular significance for Muslim ghazis. It was the seat of the greatest empire of late antiquity, and its conquest would destroy the only remaining state that could seriously challenge Muslim power—according to one hadith, the first soldier to enter its walls would automatically be granted admission to paradise.

But the capital was distant—400 miles as the crow flies from the mountainous border—and the intervening highlands of Asia Minor were not conducive to territorial conquest. Low population densities made it hard to sustain several large garrisons through winter months, for which the Arabs may well have lacked the manpower in the first place. With no real intermediate objectives that could serve as a springboard to their ultimate goal, the Arabs gradually adopted a two-pronged strategy: to lunge for Constantinople when circumstances were favorable, and otherwise to raid enemy territory year after year.

These annual raids were major undertakings, composed of ghazis from all over the Islamic world. A commander who was successful in one expedition would attract even more warriors to his banner in the future, drawn by the anticipation of loot and glory; this in turn increased the commander’s clout within the fractious politics of early Islam.

It was this combination of personal motivations with higher strategy that strongly resembled Eastern Woodlands warfare. However self-interested individual commanders might be, the cumulative effect of their actions served political leaders’ strategic interests: attritting the enemy over time, and occasionally forcing them to pay tribute during truces.

Yet there were also crucial differences. Constant depredations might force the local peasantry to vacate their land, just as Indian tribes could force rivals to abandon their traditional hunting grounds, but unlike hunting grounds, land on the frontier had little value in itself—at best this strategy of devastation eased the passage of future expeditions. The religious dimension of the conflict also expanded its scope. The Arabs could not be satisfied with even the most favorable peace short of complete submission, making the war an all-or-nothing affair with Constantinople as the ultimate prize.

Byzantine strategy was far more defensive-minded. The much-reduced Eastern Roman Empire was in desperate straits throughout the first two centuries of this period, under severe pressure from all directions—mere survival was the goal. Its military culture was more centralized and less tribal than the Arabs, their strategic objectives were paradoxically more similar to the Native Americans: defeating incursions while launching counterraids of their own to win much-needed truces and occasional tribute payment from the Arabs.

The Byzantines were ultimately able to go on the offensive and win a complete victory. But their triumph was a product of endurance, of maintaining cohesion through the worst of the tempest and gradually recovering their strength while their enemies crumbled. And when they did finally win in the 10th century, it was a victory of a very conventional sort, won by marching into enemy territory and sacking his cities. The Arab-Byzantine wars thus represent a fascinating superposition of familiar interstate dynamics and a completely alien style of warfare.

Many of the details of the earliest centuries are lost to us. They were a dark age in every sense: chaotic, violent, and mostly lost to the light of history. Our best sources were not even written until the 9th century, and they present often confused and contradictory accounts. Nevertheless, we can see clearly enough the strategic logic that governed both sides throughout the entire span of the wars. This piece will examine the dynamics established in the first century of the wars, while Part 2 will look the operational art employed in later centuries, a period for which we have more detail.

A New Enemy

The eruption of Islam out of Arabia came on the heels of the most destructive conflict of late antiquity. Between 602 and 628, the Eastern Roman Empire and Sassanian Persia fought a war that sprawled across the Near East. The Persians held the upper hand for most of that span, overrunning Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia, while even participating in the Avar siege of Constantinople (the Avars were a tribal confederation from the trans-Danubian steppe).

The Romans ultimately emerged victorious, but by that time both empires were exhausted. Their lands had been devastated, treasuries emptied, and armies blunted. Mesopotamia was hard hit by a nasty outbreak of the plague in the last year of the war. Neither was prepared to meet the armies of a self-proclaimed prophet who was then consolidating power among the tribes of the Arabian Peninsula.

The first sign of trouble came immediately after the war’s end. A Muslim war band was sent to Syria in 629, but was defeated by Roman forces east of the River Jordan. More expeditions followed Mohammad’s death in 632, when a new Caliph—leader of all Muslims—sent probing armies into Syria and Mesopotamia. They increased their efforts as they won several battles in both theaters, culminating in two crushing victories in 636: at the Yarmouk, an eastern tributary of the River Jordan, where they destroyed a very large Roman force, and at Qadisiyyah in Iraq, where they defeated an army guarding the approaches to the Persian capital.

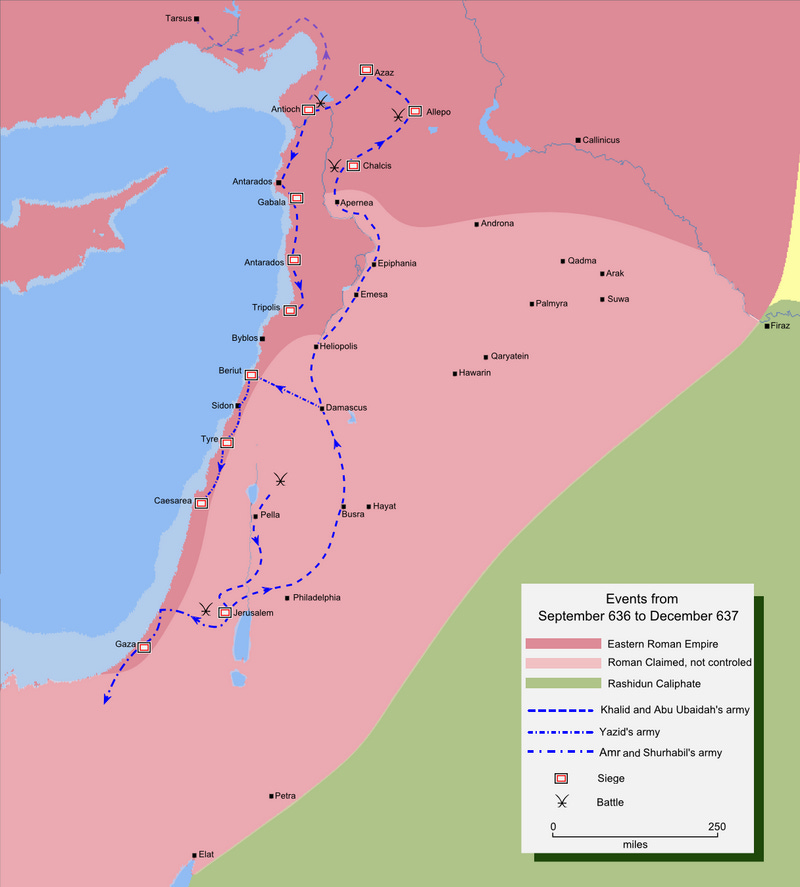

Roman losses at the Yarmouk were especially bad, compelling them to withdraw their field army to the more defensible line of the Taurus Mountains—the garrisons of northern Syria were left to fend for themselves. That same year the Arabs took Aleppo and Antioch, the two great metropolises of northern Syria, and the following year conquered up to the southern foothills of the Taurus.

Geography of the Borderlands

The Taurus Mountains stood at the center of what became the Arab-Byzantine frontier, separating the highlands of Anatolia and Armenia from the plains of Syria and Mesopotamia. Anatolia was Byzantium’s defensive redoubt over the next few centuries, occupying the western two-thirds of modern Asiatic Turkey. Although the surrounding coastal lowlands are very fertile, the vast interior plateau is a high semi-desert, suitable for grazing but only limited agriculture. Turkey’s eastern third, which is considerably more mountainous, was the heartland of classical Armenia—by this point a geographical term, not a political one, as Armenia had long since been partitioned between the Roman and Sassanian Empires.

The Taurus Mountains hug the southern coast of Anatolia, jagging northeast just short of where it meets the eastern shore of the Mediterranean. From there, the mountains follow a thousand-kilometer arc, turning southeast along their final stretch to join the Zagros Mountains (which run along Iran’s modern border with Turkey and Iraq).

At the western end of this arc, where the mountains separate from the shore at the northeastern corner of the Mediterranean, is a region called Cilicia. This was one of the most agriculturally-productive regions in the empire (as it remains today), partitioned from the northern Syrian plains by the north-south-running Amanus Mountains. The sections of the Taurus Mountains around Cilicia are the highest of the entire range, and can be crossed at only a few passes.

East of Cilicia, the Taurus mountains are much lower and easier to cross, with several river valleys, including the Euphrates, cutting through them. Beyond them, however, the Anti-Taurus Mountains run in a parallel arc from Cilicia all the way to Mount Ararat, forming a second barrier between Syria and the Anatolian plateau. The Anti-Taurus are not a single ridgeline, but rather a jumble of interlocking ranges; although a number of passes run through them, they made the eastern routes into the Byzantine heartland circuitous and difficult.

Early Incursions

The Arabs did not begin probing the line of the Taurus until the 640s, and even then fighting elsewhere dominated their attention. They were still preoccupied with the Sassanians in Iraq, who soon began launching counterattacks from their own redoubt beyond the Zagros Mountains. In 640, an Arab army crossed the Euphrates to conquer Roman Mesopotamia, while another began the conquest of Egypt. Constantinople sent an expedition to Alexandria late in 645 which tried pushing up the Nile Delta, but it was forced back the following year after tough fighting. With Egypt secure, Arab forces began pushing into North Africa.

Nevertheless, there were some large-scale raids north of the mountains. The Muslim governor of Syria, named Mu’awiyah, began launching raids in the 640s, and would eventually prove one of the Byzantines’ most dangerous antagonists. The first of these, in 641, reached the Amasia in northern Anatolia. Another expedition in 644 forced the town of Caesarea to pay tribute, then devastated the country around Amorion in western Anatolia.

A second expedition to Amorion in 646 gives some indication of how dire the Byzantines’ military situation had gotten. As the army passed through Cilicia en route to Anatolia, it discovered that all the border fortifications in the Amanus Mountains and Cilicia itself had been abandoned; after the expedition safely returned, these were destroyed. A final raid in 649 or 650 struck southwestern Anatolia, carrying off thousands of captives and plentiful loot. The mere fact that armies were able to penetrate so deep, seemingly at will, indicated that the Byzantines were desperately short of manpower and cash.

The Arabs’ other major objective was Armenia. An excursion in 641 reached a pass over the eastern Taurus range, but the first serious raid came in 642, penetrating deep into the highlands. Several more raids were launched over the next few years, from both Mesopotamia to the south and the Iranian plateau to the east.

This proved even more challenging for Constantinople. The Armenian highlands were physically distant from the capital and culturally unique, and the mountainous landscape fragmented political control amongst an aristocracy jealous of its independence. The emperor appointed an Armenian patrician, Theodore Rshtuni, to oversee the defense of the region, and occasionally reinforced him imperial troops.

By Land and By Sea

Parallel to the raids across Anatolia were raids off its coast. Egypt had been an important naval base, and its conquest had furnished the Caliphate with a large fleet. The Byzantine expedition of 645-46 may have alerted the Arabs to the importance of the sea, as they soon began sending out expeditions of their own. In 648 the fleet sailed up to Syria, whence it carried troops across to Cyprus. They devastated the island exacted tribute, then the following season used the fleet to reduce a few coastal holdouts in Syria.

This was paused in 650, when Mu’awiyah agreed to a truce so that the Caliphate could complete its conquest of Persia. The Syrian governor took advantage of the peace to subvert the Armenians (whose precise legal status with regard to the empire is ambiguous). Rshtuni threw off his allegiance to Constantinople and agreed to pay tribute, whereupon the emperor marched out to confront him in 651. This expedition failed to completely subdue the rebels, and Mu’awiyah used it as a pretense to resume the war the following spring.

Muslim arms reached a high-water mark over the next few years. Mu’awiyah sent an army to expel the remaining Byzantine forces from Armenia, bringing the country wholly under his allegiance. Rshtuni’s submission did him no good, however, as a few years later the Arabs took direct control over Armenia and sent the unfortunate prince into captivity in Damascus. In 653 Mu’awiyah led a raid into Anatolia in person which reached as far as the Bosporus, within sight of Constantinople itself. The fleet was also active that year, raiding Rhodes and Crete.

Victories at sea, paired with his glimpse of the splendid Byzantine capital, opened Mu’awiyah’s eyes to the promise of joint operations. Any attempt on Constantinople would require naval support just to reach its walls, which in turn required gaining superiority over the still-powerful Byzantine fleet. This came in 654 or 655, when the Arabs annihilated a Byzantine fleet that had sailed out in strength to confront them. With nothing obstructing either the sea-lanes or the entrances into Anatolia, Mu’awiyah seemed poised to launch a campaign against Constantinople itself.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.