Successors to the Western Front, Pt. 1: Operational Maneuver in the Greco-Turkish War

World War I came at a very particular technological moment. The new weapons that made combat so lethal also made mobile warfare far more difficult: not only did they lend the defender an edge, but their voracious appetite for ammunition overwhelmed the primitive logistical apparatuses of the time. Trains could resupply static positions, but new track could not be laid in time for a rapid advance, leaving armies dependent on animal-drawn carts and small motor pools. Just a generation or so earlier, large armies were still light enough to conduct sweeping envelopments; a generation later, they were sufficiently motorized to keep pushing after a breakthrough. But in 1914, it was both tactically difficult to penetrate enemy lines and operationally difficult to exploit it.

These peculiar dynamics were manifest everywhere during the First World War, but especially on the Western Front. The sheer number of divisions mobilized by France, Germany, and Britain left little room for maneuver, transforming the entire front into a continuous fortified line with no gaps or open flanks. Nor were breakthroughs really practical: the dense rail networks of Western Europe allowed defenders to amass huge quantities of firepower, magnifying their existing advantages while providing no corresponding benefit for the attacker.

It was thus a combination of tactical and operational factors that made the Western Front such a bloody deadlock. The much wider Eastern Front, with its correspondingly lower troop densities, was far more elastic. Local penetrations and envelopments could be exploited, sometimes shifting the front several hundred kilometers in a single campaign, with correspondingly greater hauls of prisoners.1 From mapsinanutshell:

Yet World War I was not the only conflict fought with such technology. The 1918 armistices were the beginning of a new round of wars just as much as they were the end of the last: over the following decade, several conflicts erupted fought with the same machine guns, artillery, airplanes, and rail. The following decade provides a number of case studies in how contemporary weapons shaped the relationship between tactics and operations in varying conditions. The Russian Civil War was the largest and best known of these, fought on a similar scale to the Eastern Front. Most of the combat was even more fragmented and fluid, although it became entangled with other conflicts, such as the Polish-Soviet War, which were fought across dense and continuous fronts.

The decade witnessed several other wars that are much less well studied yet are of interest. Two in particular stand out: the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922 and the Chinese civil war of 1924, sometimes called the Second Zhili-Fengtian War. Both saw intense combat between vast numbers of men equipped with machine guns, artillery, and airplanes, fighting on dense fronts tied to rail corridors. Yet neither was fought on so long or continuous a front as existed in northern France. Lines of contact were much shorter, usually formed under more dynamic circumstances and in different terrain, creating many more opportunities for operational maneuver. As a result, major battles never lasted more than a few weeks and often ended decisively.

These case studies have especial resonance today. Modern firepower seems to give the defense an edge, while tightly binding operations to narrow supply corridors; yet Ukraine remains our only point of reference for large-scale near-peer conflict between 21st-century militaries. Heavily-fortified lines stretching hundreds of kilometers through open country draw inevitable comparisons to the Western Front. Yet it is precisely those conditions which are unlikely to be replicated in a future war. Studying similar-but-different examples is therefore a useful exercise in broadening our frame of understanding. This piece will examine the Greco-Turkish War, and we will look at the Second Zhili-Fengtian War in the next installment.

The Greco-Turkish War

The First World War ended slightly earlier in the Middle East than on the Western Front, but took much longer to resolve. An armistice between the Ottomans and Allies went into effect on 31 October 1918. This left the British and French in control of most of Syria and Iraq, the Greeks in control of nearly all European Turkey, and mandated an Allied occupation of Constantinople.

Subsequent negotiations over territorial changes to the Ottoman Empire were complicated by its multiethnic nature. Even if reduced to Anatolia, its borders would encompass large numbers of Greeks, Armenians, Kurds, and Arabs, who all wanted states of their own. As the matter was being discussed, the Allied administration authorized temporary occupation zones along the coast. The French had already occupied Cilicia, the lowland region at the northeastern corner of the Mediterranean, in November; in April 1919, the Italians landed at Antalya in southwest Anatolia, followed in May by the Greeks at Smyrna in the west.

The Allies were by this point far from unanimous on what to do. The major powers favored a unitary Turkish state in Anatolia, with occupations a temporary measure, but Greek ambitions went farther. Smyrna and its surroundings were majority Greek, and they hoped to incorporate it and other territory into a larger Greece that encompassed all the shores of the Aegean.

Turkish nationalists watched these developments with dismay. Among their leaders was the Ottoman war hero Mustafa Kemal, the future Ataturk, who issued a call to form a new Turkish state. Gathering in the highlands of the Anatolian plateau, the Nationalists set themselves against Sultan Mehmed VI, who still reigned in Constantinople, and organized government bodies and militias. Nationalist irregulars soon began attacking Allied forces in the occupation zones, and by spring 1920 forced French garrisons out of several cities in northern Syria.

As the fighting intensified in 1920, the Greeks undertook a major summer offensive. Forces advanced along the rail lines running north and east from Smyrna, and British ships landed Greek troops on the Sea of Marmara and provided naval gunfire as they advanced inland. By the end of the summer, the Greek Army of Asia Minor had established bases of operation at Bursa in the north and Uşak in the south, the second of which was in the highlands of the Anatolian plateau.

In the midst of all this, the Sultan’s plenipotentiaries signed the Treaty of Sèvres with the Allies on 10 August. It formally ceded the territory around Smyrna to Greece and large parts of eastern Anatolia to Armenia; it mandated independence plebiscites in Kurdish regions in the southeast; established a demilitarized international zone around the Dardanelles and Bosporus; and established further British, French, and Italian occupation zones.

News of the treaty energized the Nationalists, who saw its concessions as a betrayal of Turkish sovereignty. That fall, Nationalist forces fought to contain French expansion from Cilicia and to occupy Armenian territory—the latter coincided with the Soviet occupation of eastern Armenia, bringing the two states’ borders against each other. The majority of Nationalist efforts, however, went to organizing their Western Front, which faced the greatest threat to their movement.

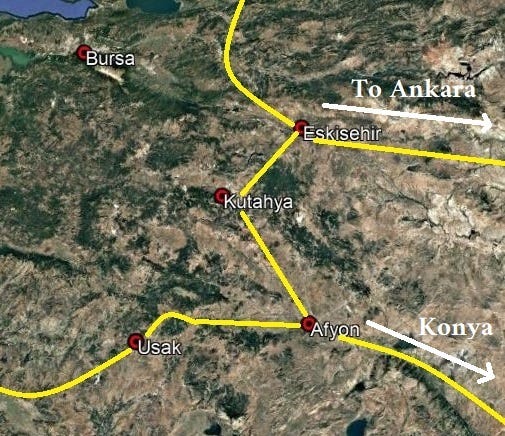

Advances into Anatolia

In March 1921, the Greeks launched another major offensive into the Anatolian plateau, with the aim of bringing the Nationalists to heel. The Turks occupied strong positions anchored on Eskişehir and Afyonkarahisar (henceforth shortened to Afyon). Both were important rail junctions, connected to each other by the main Constantinople-Baghdad line. This line ran 50 km west from Eskişehir before turning north to the Ottoman capital, making it easy to supply the positions that guarded the approaches from Bursa. A separate branch also ran east from Eskişehir to the Nationalist capital at Ankara. On the southern front, the branch running from Smyrna merged with the main line at Afyon, where it then continued on to Konya, another Nationalist base. Roughly midway between Eskişehir and Afyon stood Kütahya, on a spur off the main line.

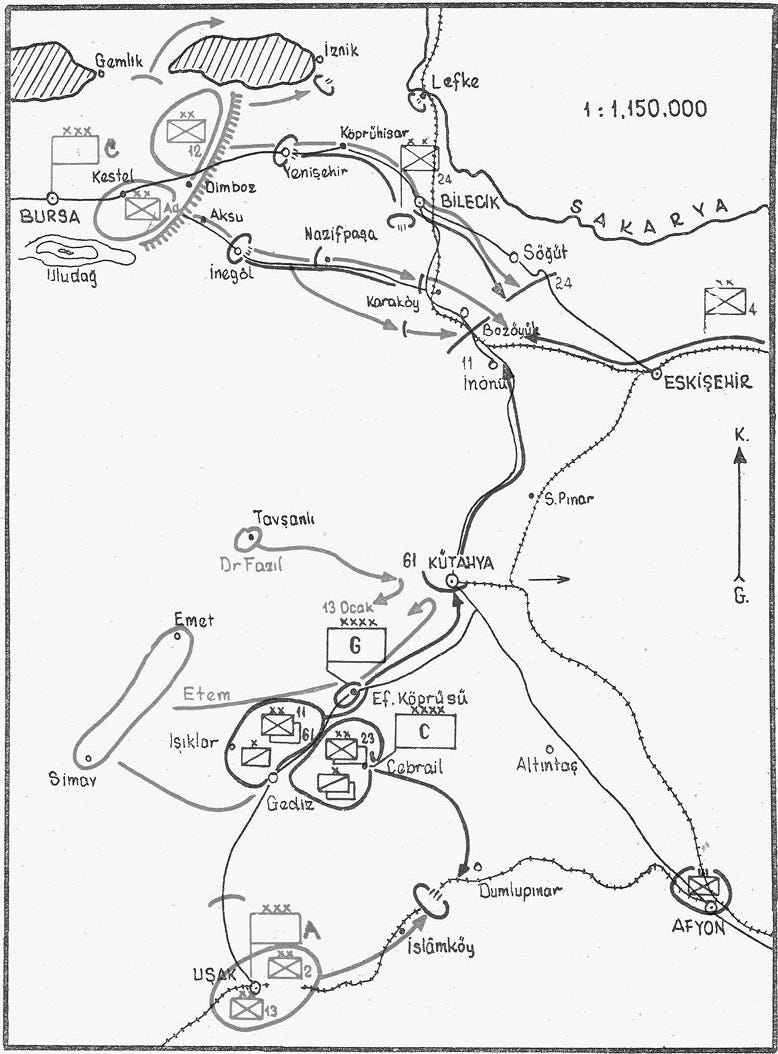

The Greek situation was much tougher. Although they could advance on Afyon by rail, they enjoyed no such advantage in the north. There they had to march along the old Dorylaeum2 road, used centuries before by Byzantine and Crusader armies to campaign against the Turks, which passed through valleys and hilly country. A reconnaissance-in-force that January had been repulsed about 30 km west of Eskişehir, showing that the Turks maintained substantial defensive capability.

The Greek offensive was therefore to be much more elaborate: 100,000 troops were to advance on two axes: 40,000 men in III Corps would march on Eskişehir, while a vanguard of 22,000 men from I Corps advanced on Afyon from Uşak.

The Turks had meanwhile been receiving reinforcements. At the end of the previous year, they had ended fighting on their eastern border with Armenia, then just two weeks before the Greek push, they had signed an initial treaty with the French in Cilicia. This freed up enough troops that they could gather about 60,000 to defend against the onslaught facing them. They focused most of these around Eskişehir, which guarded the way to Ankara.

The offensive began on 23 March. The southern grouping easily accomplished its initial objective, occupying Afyon by 28 March, although the defenders escaped in good order toward Kütahya. III Corps faced greater difficulties, struggling through difficult country and facing improved defensive positions. After a week of tough fighting, the Greek corps was unable to break through Turkish positions and found itself running short on supplies. The Turks had managed to concentrate up to 40,000 soldiers west of Eskişehir, and their counterattack forced the Greeks to withdraw, which they managed in good order. The Turks then turned their attention to the southern front, where two weeks later they forced the two corps at Afyon to pull back in turn.

The spring campaign showed just how critical rail was to offensive operations. In the south, where the Greeks were advancing along a single line, they were able to put their advantage in numbers to good use; in the north, they were unable to sustain the attack. The Turks, for their part, controlled a much more extensive network which connected Eskişehir to Afyon and both cities to points farther east. This allowed them to bring in reinforcements from out of theater, to conduct an orderly withdrawal from Afyon, and to shuttle troops back and forth between points of crisis—first to Eskişehir, then back to Afyon.

The Summer Offensive

Both sides continued to build up their strength over the following months, fielding a total of 120,000 troops against 70,000 Turks. The Greeks resumed their advance in July: for a third time, two divisions of III Corps marched on Eskişehir, while two divisions of I Corps marched on Afyon in the south. The main blow, however, was directed against Kütahya, midway on the rail line between the two cities.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.