The Ethiopian Air War: Hints of the Future

Azerbaijan’s invasion of Nagorno-Karabakh in the autumn of 2020 sparked a lively debate over how loitering drones would shape the future of warfare. Some declared the end of the tank, while others argued that the new weapons simply marked an incremental shift in the composition of combined arms. The war in Ukraine has definitively answered this question, showing that loitering drones are indeed not a wonder-weapon. Although they certainly have a role to play, they enjoy far less success in the face of capable air defenses, and have been overshadowed by much humbler—and cheaper—reconnaissance drones used to relay targeting information to ground-based artillery.

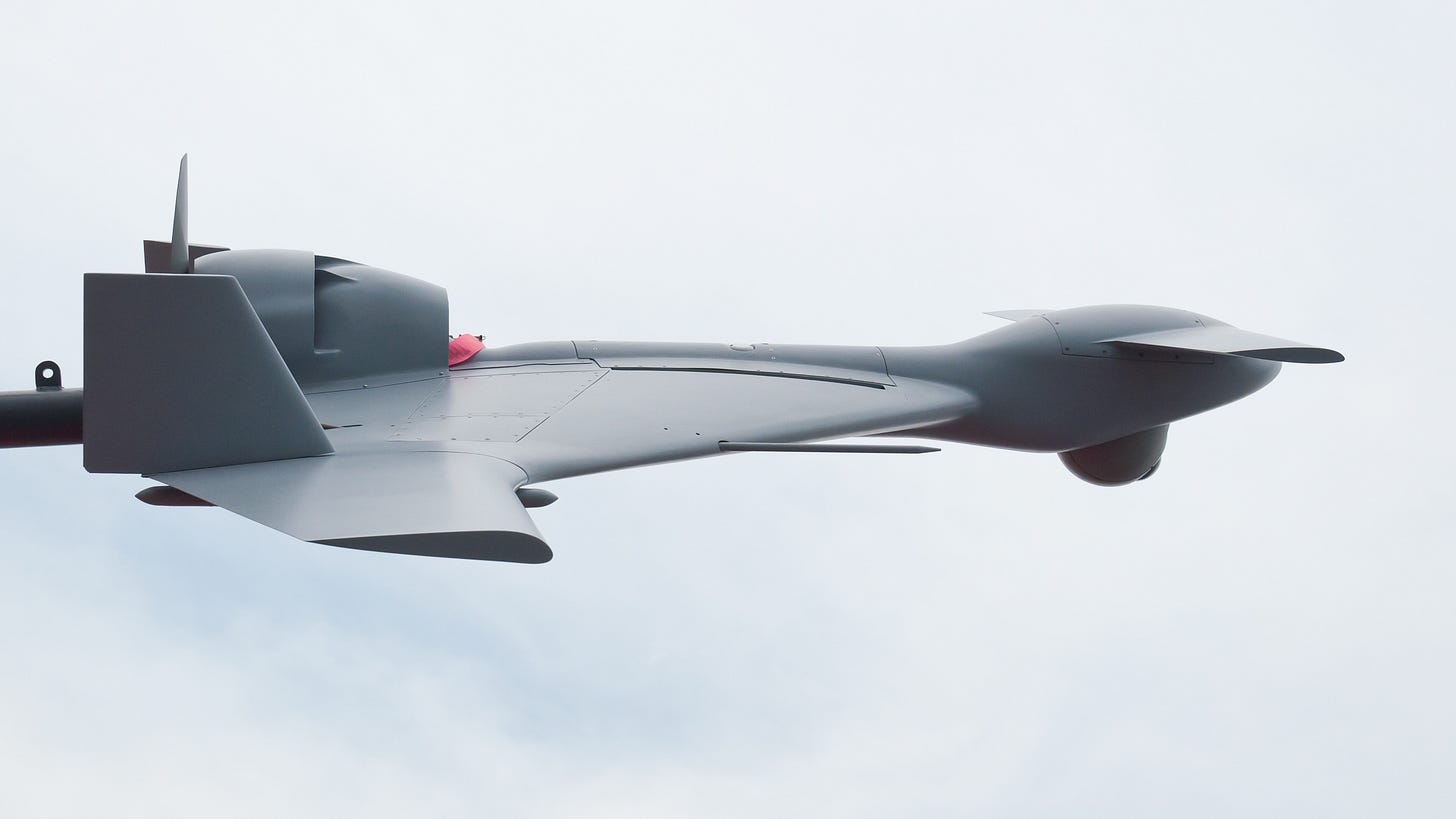

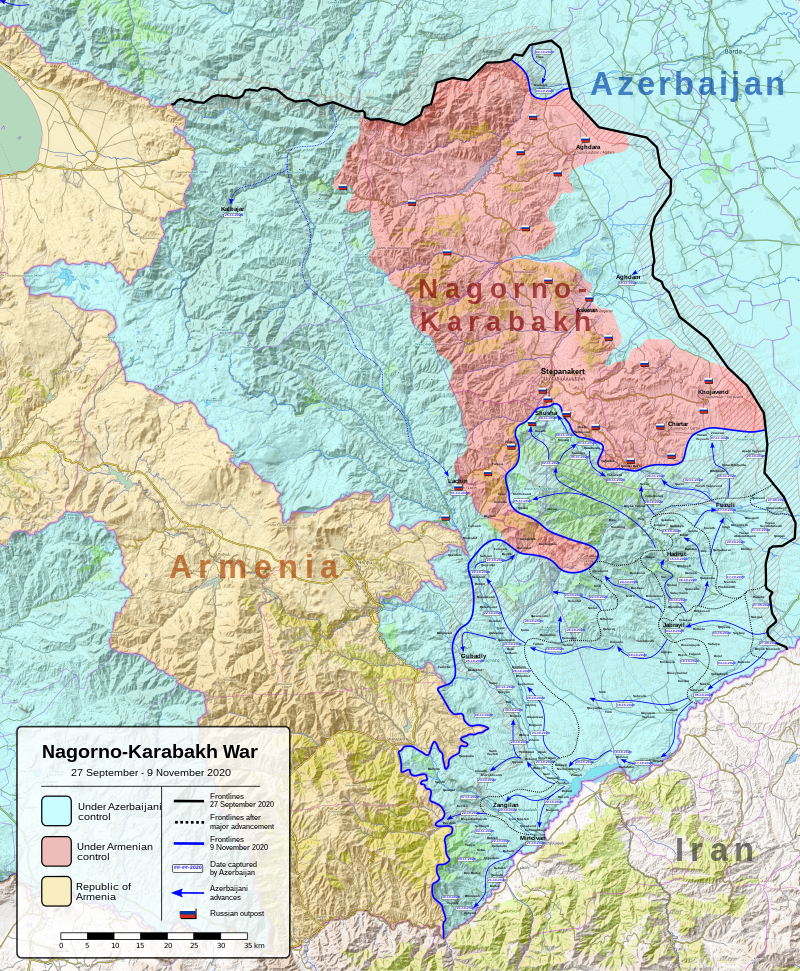

The Nagorno-Karabakh War was different from Ukraine in several ways. Azerbaijani ground forces had continuous fire support in the form of Turkish TB-2s and Israeli Harops; although these faced extensive if outdated air defenses, Azerbaijan’s drones were able to suppress and destroy these even as they targeted Armenian ground forces. As a result, Azerbaijan was able to advance through difficult mountainous terrain against a dug in enemy in just 44 days.

In many ways, this foreshadowed another conflict: the recent civil war in Ethiopia. Over the course two rapid campaigns, government forces supported by foreign-supplied UCAVs were able to make rapid progress and compel the rebels to peace. Like Nagorno-Karabakh, this entailed an offensive into mountainous terrain that favored the defender. Together, these examples point to a future pattern for smaller conflicts around the globe.

Outbreak of the War

The Tigray War began in November 2020, with fighting between the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) and the newly-formed Tigray Defense Force (TDF). During the first few days of hostilities the TDF captured large quantities of weapons and equipment from army bases in the regional capital of Mekelle, but were soon faced with an offensive on multiple fronts—ENDF forces attacking from the south and Eritrean forces attacking from across the border to the north. Within weeks, the ENDF had captured Mekelle, and by the end of the year it controlled most of the major roads in Tigray.

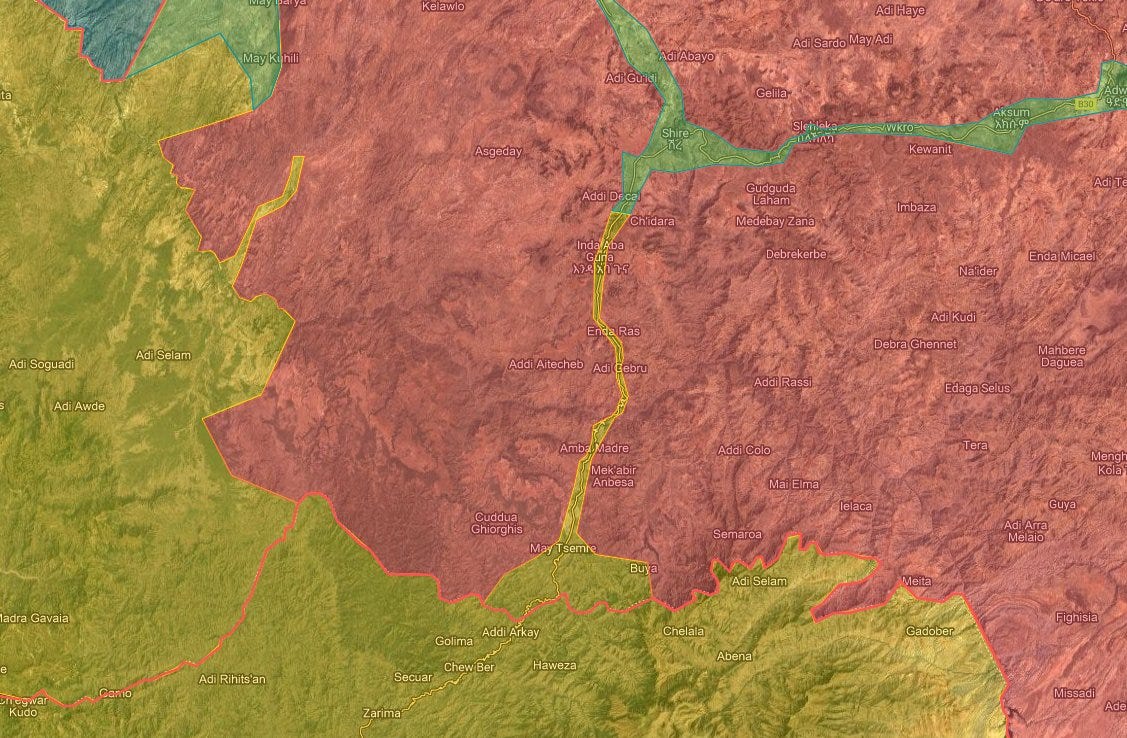

Several months of guerrilla warfare ensued, during which the TDF had some successes. In June 2021 they recaptured Mekelle and most of Tigrayan territory, which they followed up with a push south into the neighboring Amhara region. In mid-October, the TDF launched a new offensive which saw spectacular gains as it moved south along the A2 highway. Within six weeks, they had reached within 200 km of the capital Addis Ababa.

Drones Turn the Tide

The rebels’ rapid progress alarmed many Middle Eastern governments, which had various interests in Ethiopia and feared instability spreading across the broader region. Several of these began providing UCAVs to the government: Turkey with TB-2s, Iran with Mohajer-6s, the UAE with Chinese-made Wing Loongs, and Israel with unarmed reconnaissance drones.1

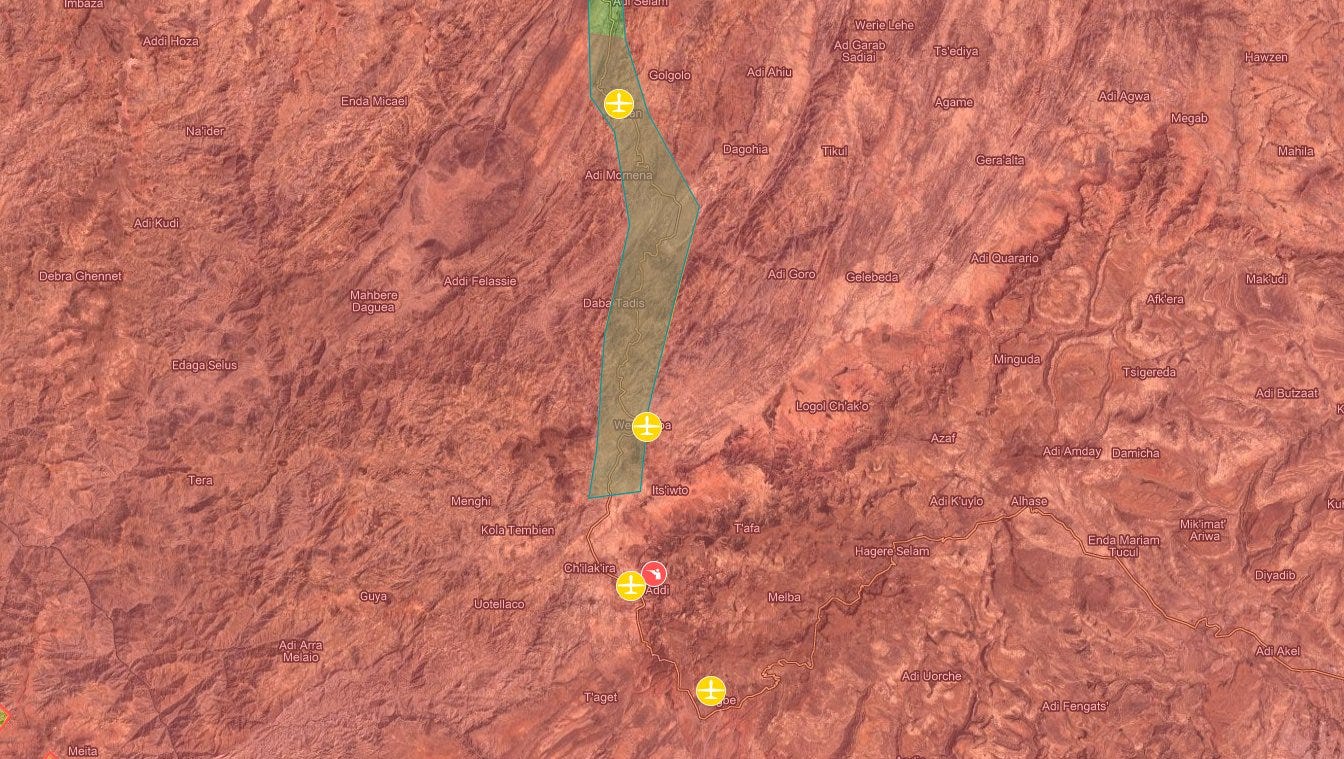

The ENDF launched a counteroffensive at the end of November which succeeded in stopping the Tigrayan advance in its tracks. The new drone deliveries were effective in striking Tigrayan positions, while attacks at multiple points along the A2 forced the TDF into precipitate withdrawals to avoid being cut off. By 21 December, government forces had reached the border of Tigray itself.

Ethiopian Air Force

Drones were also used in conjunction with manned aircraft. The Ethiopian Air Force (ETAF) had a modest fleet of Su-27s, Su-25s, and older MiGs which proved capable in the 1998-2000 war with Eritrea. This force was not upgraded in the meantime, and it appears that some aircraft were no longer operational by the time of the Tigray War. For instance, there is little evidence that any of its Su-25s were used—this is a dedicated ground-attack aircraft ideally suited for the mission profile of the conflict. Its inventory of aging MiG-23 fighter-bombers was also limited.

The ETAF was instead forced to rely on its more abundant Su-27s.2 This is an air superiority fighter, lacking the armament, targeting systems, or pilot training to effectively strike ground targets. Even before receiving large numbers of UCAVs, however, the government used the Su-27 as a stopgap, reportedly pairing them with unarmed Wing Loongs used to designate targets.3

It is impossible to tell just how effective these measures were, and there were many reports of wildly inaccurate strikes hitting civilian areas. Given the dramatic turnaround after the government acquired large numbers of UCAVs in the last half of 2021, it is unlikely that manned aviation played a decisive role. This is similar to Nagorno-Karabakh, where Azerbaijani pilots flew only ~600 sorties over the course of that conflict (although for very different reasons—Armenian IADS, although substantially degraded in the first few days of fighting, remained a threat).4

Advances into Tigray and End of the War

The ENDF was slow to advance after reaching the border of Tigray, but launched numerous airstrikes over the next several months. The two sides agreed to a ceasefire in March 2022, but this broke down the following August, after which ENDF and Eritrean forces began pushing deeper into TDF-held territory.

Tigray is a mountainous region, limiting the possible axes of advance to a handful of major roads.

All else being equal, this makes it difficult even for superior attacking forces to amass sufficient combat power to dislodge dug-in defenders; unsurprisingly, advances were accompanied by heavy manned and unmanned airstrikes.

The geography resembled Nagorno-Karabakh, where after making rapid progress on the plains, Azerbaijani forces faced fierce resistance before breaking through to cut off Armenian forces. It was there that TB-2s and Harops proved decisive.

Although Tigrayan leadership held out in Mekelle, they agreed to talks in late October. On 2 November, the two sides reached a permanent end to the fighting, whereby the TDF would disarm and disband.

Patterns for the Future

The Tigray War was defined by many unique factors of scale, opposing forces, geography, and political situations that are unlikely to be found elsewhere—we must always be cautious about drawing any universal lessons from one war. Nevertheless, there were two key factors that are likely to be present in many future conflicts:

1) Lack of sophisticated air defenses. Although the TDF reportedly shot down several manned aircraft with MANPADS, these were unable to interfere with the drone campaign which accompanied the successful ENDF counteroffensive.

2) Willingness of foreign actors to provide support. Emirati, Turkish, and Iranian aid proved decisive in the conflict, capable of rapidly reversing the situation within months, just as Turkish and Israeli support proved decisive for Azerbaijan’s 2020 offensive.

Drones strongly favor the aggressor, and most countries lack the air defenses to counter them. At the same time, many middle-tier militaries are investing in their own drone industries and fleets. Taken together, this offers a strong incentive for outside actors to interfere in civil conflicts; the low barrier for entry also invites those actors’ competitors to intervene, setting conditions for chaotic proxy wars where both sides have strong offensive potential.

The counterargument is that it is just as possible for outside countries to provide air defenses, as Turkey did for Libya in 2020. The provision of both SAMs and drones allowed the government to halt a rebel offensive on Tripoli and mount its own counteroffensive. This effectively froze the civil war along stable lines, allowing for outsiders to broker a ceasefire.

Sophisticated IADS represent a proportionally larger investment, however, and the economics of production mean that the requisite missiles, guns, and radars will always be a scarce resource. Turkish involvement in Libya was moreover contingent on a long coastline, within range of their naval radars;5 attackers, by contrast, have much greater flexibility. Ultimately, this only increases the likelihood that unstable countries across the globe will be at risk of seeing domestic instability bloom into all-out civil war. These conflicts might not look much like the Tigray War in their particulars, but the underlying patterns will likely be similar for the near future.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

https://www.oryxspioenkop.com/2021/10/from-mohajer-6s-to-wing-loong-is.html

14 reportedly in active service: World Air Forces Directory 2022, p. 18.

https://www.oryxspioenkop.com/2021/11/deadly-ineffective-chinese-made-wing.html

https://www.militarystrategymagazine.com/article/drones-in-the-nagorno-karabakh-war-analyzing-the-data/

For more on the Turkish intervention: https://www.mei.edu/publications/turning-tide-how-turkey-won-war-tripoli