The Evolution of Ranks and Units

I mentioned in passing in a previous piece how mercenaries were integral to the development of modern national armies. This is revealed in the evolution of rank and unit structures which took place over the long transition from feudal to standing armies. Taken as a whole, it gives us an interesting perspective on the intertwined problems of recruitment and tactics.

The Medieval Inheritance

There were few true ranks in the Middle Ages. The only permanent offices were those of constable and marshal. These derive from respective Latin and Germanic terms meaning “keeper of the stables”, used in Roman times to designate the commander of the cavalry, and later by extension the entire army. Both became high royal offices in the kingdoms of Western Europe, while marshal was also used more informally for the commanders of field armies or major contingents.1

Feudal armies were raised by the lords of the realm, who when summoned were obligated to bring a retinue of knights and a certain number of other cavalry and foot soldiers. Among the cavalry were lightly-armed soldiers called sergeants: of lower social status than knights, but generally wealthier than the common foot soldier—as of yet this was only a class of soldier, not a rank.

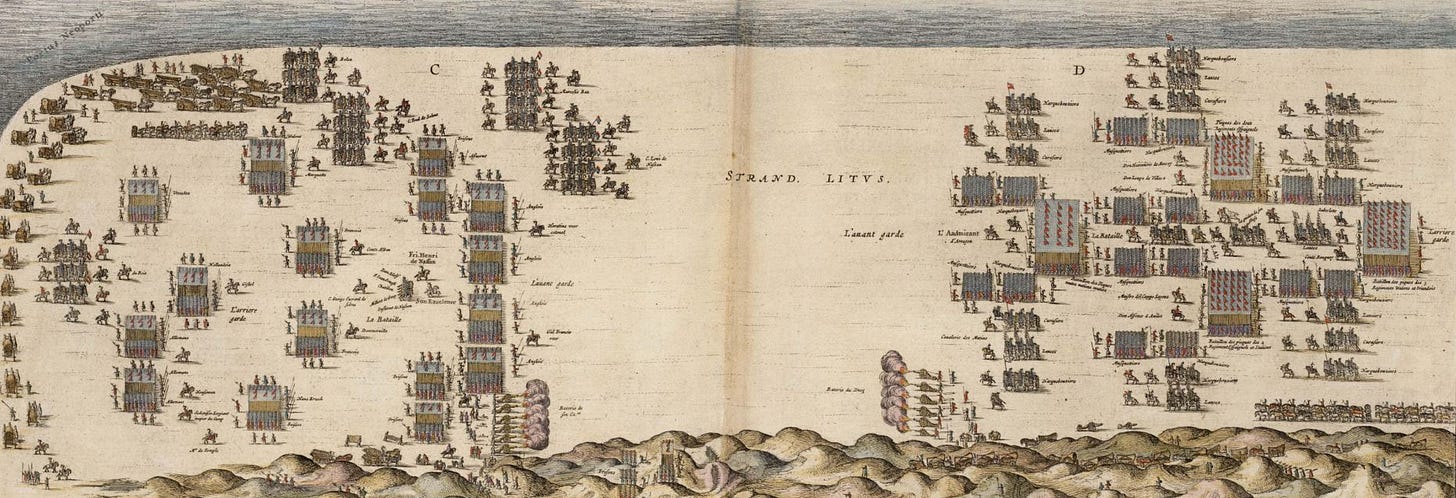

These contingents, called companies, were not standardized, but depended entirely on their lord’s terms of feudal service. Nor were they independent tactical units: several companies were usually combined into “battles”, formations of cavalry, archers, and other foot soldiers under the command of some great noble. Armies were traditionally drawn up into three great battles: the vanguard on the right, main battle in the center, and the rearguard on the left. Larger hosts were often formed into even more, however, and individual units gradually shrank in size—toward the end of the period, it was not uncommon for an army to form up in ten or more. Within each battle, the cavalry was organized into several smaller tactical units, variously called banners, conrois, or squads, anywhere from ten to several dozen men. The infantry was drawn up in a separate bloc within the battle, organized into similar subdivisions.

Contracts and Companies

As the feudal system began to break down in the later Middle Ages, it was replaced by recruitment on contract. This retained most of the forms of feudal service, but substituted land tenancy with cash payment. Great lords were commissioned to raise a certain number of troops of various sorts, which they then subcontracted to their retainers.

Some of these companies became semi-permanent institutions, traveling around Europe in search of employment. A famous early example was the Catalan Company, formed from veterans of wars in Sicily, which in 1302 sailed east and rampaged across the remnants of the Byzantine Empire. Later that century during the Hundred Years’ War, free companies—not necessarily led by any great noble—took to banditry across France. Many of these traveled abroad, where they found employment with the cash-rich but manpower-poor city-states of Italy. It was in Italy that the word captain became associated with the company. In France and England, captain was a rather more exalted office, usually the commander of a city or town. But in Italy it was used more broadly for any kind of military chief, and quickly became the default term for the commander of a company.

Mercenary companies naturally varied widely in size: they could be anywhere from barely a hundred to several thousands, depending on the prestige of the commander and the needs of his patron. It was the growing requirements of centralized states that brought about standardized formations, along with a more formal officer hierarchy. The French were the first to do this in the 1440s with their famous compagnies d’ordonnance, several units composed of a few hundred men-at-arms, archers, and foot soldiers each—the first standing army in Western Europe. These evolved into mostly cavalry formations, however, as French kings relied increasingly on Swiss mercenaries for their infantry.

The Spanish soon followed their example, experimenting with combined-arms infantry formations on the battlefields of the Italian Wars. The standard unit was the company or captaincy (the exact usage varied with time). Each captain was aided by a junior officer, the ensign, and two sergeants. This was the first time “sergeant” was used as a specific position, not just a type of soldier, something like a modern non-commissioned officer. Below the sergeants was another type of non-noble officer, the two cabos de escuadra, or squad chiefs.

Field Grades

In 1505 the Spanish created larger units called “columns”. These were composed of several standardized companies and commanded by a “head of column” (cabo de colunela)—this became colonel in other languages. In 1534 columns were replaced with the more famous tercios, formations about 3000 strong organized into twelve companies, each with a captain, ensign, a single sergeant, and ten corporals. The entire tercio was commanded by a maestre de campo, whose staff consisted of an adjutant, quartermaster, and staff captain. He was also assisted by a sergeant major, responsible for forming up the companies just as company sergeants formed up the squads—something which made him superior in rank to the captains. This was eventually shortened to just major, perhaps because of the non-noble implication of the word “sergeant”.2

The same year that the Spanish established the tercios, the French experimented with their own large infantry formation, the legions. Like their Roman namesakes, each was to be composed of 6000 men, recruited from a specific region in France under the command of a colonel. They were further divided into six bands, each commanded by a captain who was assisted by several junior officers, including sergeants and squad chiefs.

These legions did not last long, however. They were too expensive to maintain and the large bands were unwieldly as recruiting units. They did leave two important legacies, however. As already mentioned, prior to the 15th century, the term “captain” was used in France mostly for the commander of a place. His deputy was called a lieutenant—literally “place-holder”. Once the French started using “captain” for the commander of a band/company, his deputy was casually called his lieutenant, especially when the captain was a great lord who spent long periods away from the army. The 1534 regulations establishing the legions also formalized this position, making it a subaltern rank above ensign.

The second legacy was the birth of the regiment. Because of the difficulty of maintaining full-strength legions, they needed to be complemented by units specially-formed in times of war. These regiments took their name from the authority their commanders had over them, as dictated by their commissions (similar, in a way, to how Italian condottieri took their name from the condotta, or contract, which governed their service). Commanders of these new units were also called colonels (legionary commanders had meanwhile been renamed mestre de camp, once again chasing Spanish fashion).

The regiment soon replaced the legion altogether in France, but it was mercenaries who spread it to the rest of Europe. French kings had trouble mobilizing large numbers of homegrown infantry, and were soon forced to augment it with the aid of mercenary contractors, who had the contacts and financial networks to raise troops quickly. Most of these contractors were from Switzerland and Germany, the traditional recruiting grounds for French infantry, and they quickly took to the new regimental organization. Colonel-contractors subcontracted their commissions to their captains, who were tasked with raising a company of men in a specific district—similar to a feudal levy, if via a different mechanism. A captain’s obligation to his colonel only lasted for the duration of the contract, but they often developed working relationships with each other which approached the permanence of a standing formation.

The widespread adoption of regiments by mercenary contractors compelled other national armies to follow suit—even the Spanish started using the term for tercio-sized units raised in Germany or Burgundy. By the end of the 16th century, the template was pretty well established. The colonel was aided by a lieutenant colonel—originally the senior captain in the regiment, but by this point a separate position—and a sergeant major—soon just major. The company commanders had under them lieutenants, ensigns, and sergeants, and squad chiefs—now called corporals, from the Italian caporale, meaning the head of any small group of men.

General Officers

So much for the main field-, company-grade, and non-commissioned ranks. But what of the commanders of armies? The rank of marshal remained in use, but they were not the only ones to command armies. The term captain general had been in use since the later Middle Ages. Italian city-states also used it for the commander-in-chief of their entire military, usually a great mercenary captain. The monarchies of Western Europe adopted it for the commander of all their forces in a particular theater; they also used the term lieutenant general for this, to indicate that this authority was delegated from the king, who remained commander-in-chief of the armies. By the end of the 15th century, “general” was the default term for army commanders that “marshal” had once been.

A few other national peculiarities remained. The French used colonel general for the heads of separate arms—originally, the French infantry, the foreign infantry, and the cavalry. This rank lasted into the 19th century, and was later adopted by the Prussian and Red Armies for the rank below Field Marshal. In the 17th century, the English also adopted sergeant major general, soon shortened to major general: this ranked below lieutenant general and full general, recapitulating the regimental hierarchy within general officer ranks.

The Influence of Tactics

Companies and regiments evolved more for administrative reasons than tactical. On the battlefield, armies were organized into several larger fighting units commonly called battalions—meaning large “battles”. The medieval “battle” had steadily shrunk over the ages, but the new shot-and-pike tactics of the 16th century demanded a return to large blocs of men. Among the cavalry, the term squadron (or “large squad”) was preferred, although some armies used this term for infantry formations as well.

These formations were ad hoc, decided at the discretion of the general, but they usually combined two or more regiments or tercios. As command-and-control got more refined and firearms improved, battalions and squadrons became smaller, repeating the pattern of late medieval formations. By the early 17th century, it had become common to form two battalions out of a single regiment: one commanded by the colonel, the other by his lieutenant colonel.

The next two centuries saw several other generic terms turned into larger tactical combinations. The Swedes under Gustavus Adolphus organized squadrons into brigades, which the French combined into divisions in the mid-18th century; under Napoleon, divisions were then organized into corps. At the opposite end of the spectrum, platoons (meaning a small mass of men) appeared in the mid-17th century as a firing unit: a section of each company fired all at once, which created a more devastating effect than firing by ranks. The following centuries would see even more experimentation with formations as technology evolved and armies grew bigger: combat teams, Kampfgruppen, army groups, fronts, etc. Yet the underlying organizational foundation remained a product of the 15th and 16th centuries.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Royal constables outranked royal marshals, but constable was also a parish-level officer of the peace (origin of the modern constabulary) whose commands could be called up in times of war—making them in effect low-ranking captains.

This was Charles Oman’s hypothesis in his History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century. The rank of sergeant major reappeared as a senior sergeant in some European armies in the 18th century.

What an informative and interesting article! Thanks!