The Language of Strategy: Theaters of War

The basic vocabulary of modern military science was formed in a short 150-year period, from roughly 1650 to 1800. Theaters, operations, campaigns, strategy, tactics, logistics, lines of communication—all entered into common usage during this time. This new language accompanied a step-change in the complexity of warfare, wherein the administrative capacity of states caught up with the ability of banking networks to finance large forces. European states began regularly fielding large, complex armies on multiple fronts for several years at a time, requiring suitable language for the extensive planning and coordination involved.

Yet it is also surprising how late such a vocabulary evolved. Europe had seen multiyear, multifront conflicts a century before during the Italian Wars, but did not speak of “theaters”. Despite several infantry revolutions over the previous few centuries, the word “tactics” did not enter common usage until the middle of the eighteenth century; “strategy” came later still. Concepts floated in the ether, waiting for an apt label to give them flesh. The names eventually settled upon are interesting in themselves because they embed certain assumptions about the nature of war and how it should be fought. As these still shape our strategic thought, it is worth examining them more closely.

One of the earliest such terms was theater. To say that a place had become “the theater of war” had long been a poetic cliché meaning that war had broken there or that it was the scene of recurrent fighting—usually intended to evoke the horrors of war. Over the course of the seventeenth century, this evolved into a term of art to denote the specific areas that fighting occurred within a war—i.e. it described the extent of a particular war, not the conditions of a particular country.

It was a useful term for statesmen and generals. The question of where to commit forces and what to prioritize was not always obvious. Although some regions such as Flanders and Lombardy were perennial scenes of conflict among the great powers, the intricate web of alliances that defined European warfare of the time made other theaters a point of debate. Some regions were ill-suited to support large numbers of men, and allies did not appreciate hungry armies tramping through their lands. Other regions might be avoided to keep neutral powers from getting involved—Britain was later famously sensitive towards her interests in Antwerp and Hanover—but this could also cede the initiative to the enemy. As diplomacy broke down and coalitions headed toward open hostilities, deciding upon the principal theaters of operation was a matter of urgent concern.

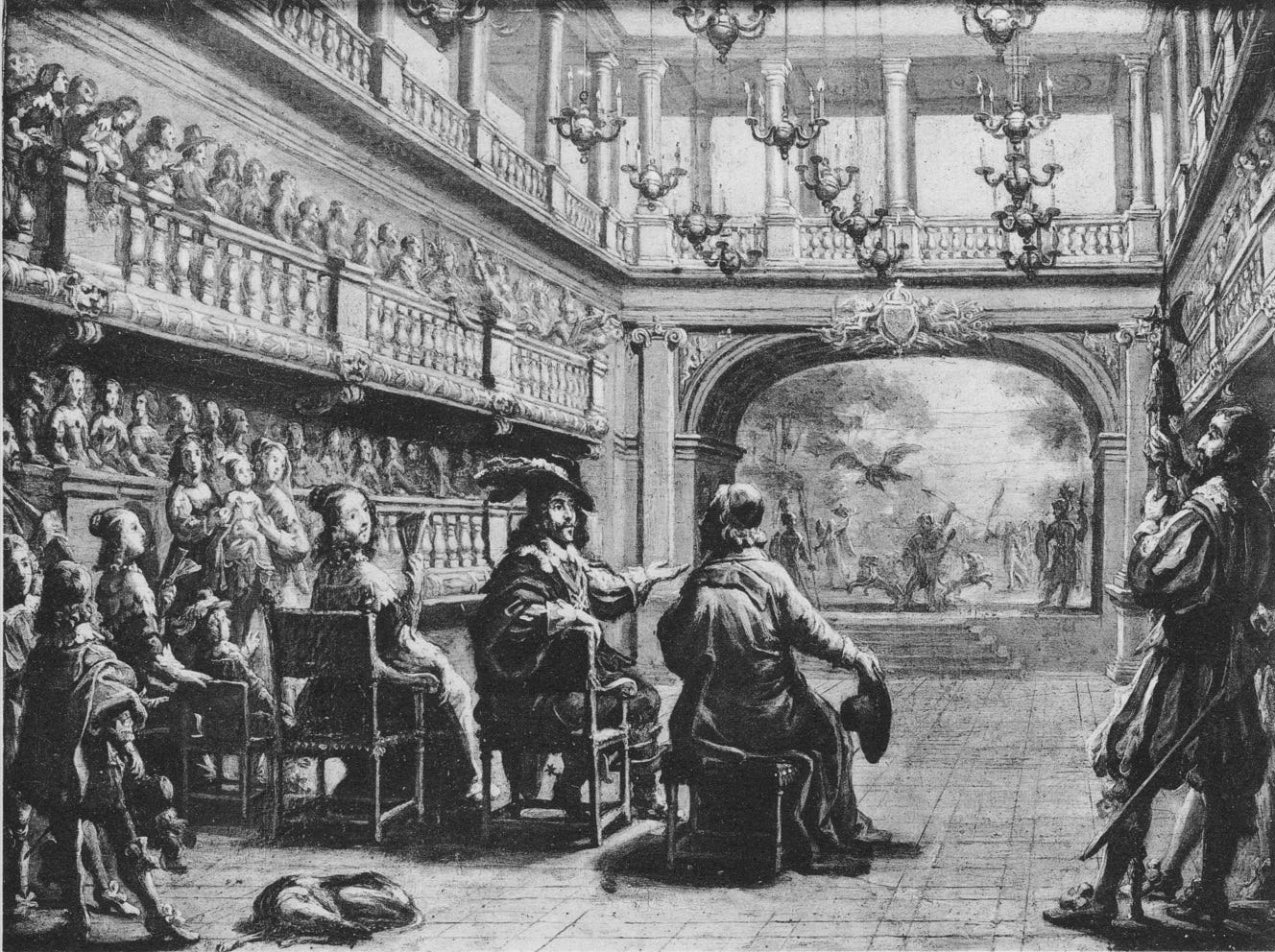

Why theater, though? This was far more than just a convenient label. The 17th century was the era of the neoclassical stage, governed by a set of formal rules. Stage dramas were supposed to conform to the three classical “unities” of place, time, and action: a play should be set in one location, transpire within the span of a day, and focus on a single plot. The metaphor naturally extended to warfare, with each theater providing the setting for the major dramas.

By itself, a theater of war only defined one of these unities. But at the exact same time that it was becoming a term of art, a complementary term entered common usage: the campaign. “Campaign” is an anglicization of the Romance word for “open country” (campagne in French, campagna in Italian). It had long been common in those languages to speak of armies taking the field (se mettre en campagne); by the year 1650, campagne was used to refer to the activity of an army in the field—this first appeared in French, then was rapidly adopted into German, Dutch, and English.1 Campaigns, like theaters, were spoken of as things that could be anticipated and planned for at the outbreak of hostilities, organized around a central design.

There was a time element to this as well. Muddy winter roads and the need for forage limited the fighting season to a window from late spring to late autumn, within which all major actions had to be conducted. A campaign was therefore expected to transpire within six months, give or take, just as a drama should take place within twenty-four hours. Thus, by the middle of the 17th century, military planners had developed a vocabulary which encompassed the classical unities: the theater for the place, the campaign for the time and the action.

Whether this was done consciously or not, no one could fail to understand the implicit metaphor. And it is a very revealing one: it shows how, contra the later Clausewitzian view, leaders saw the campaign as the principal means of shaping a war—not the battle. From the Franco-Spanish War of 1635-59 through the War of the First Coalition, all major European wars were fought in multiple theaters over several years.2 Planning was to be conducted accordingly: it was only rarely that any one theater offered even the hope of bringing the war to a rapid end. Indeed, wars of single decisive campaigns, whether involving the large coalitions of the Napoleonic Wars or just two countries such as France and Prussia, were a decidedly 19th-century anomaly.

This has many interesting implications for how states thought about and planned for war. We will look at this more in the next installment of this series, on the conceptual origins of tactics and strategy.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

The Italians used the phrase “making a campaign” (fare la campagna) as far back as the days of the condottieri to mean an excursion in open country. This did not convey the modern sense of a coordinated set of operations, however, and was often used to make a distinction with the sedentary activity of a siege—it was something more like a chevauchée. The Germans had long used the word Feldzug in a similar sense, which soon took on a broader meaning and replaced the loanword Campagne.