The Levels of Warfare, Part 2: The Birth of Tactics and Strategy

We left off in part 1 in late antiquity with the Strategikon, which marked a shift in ancient military thought. Classical antiquity held tactics to mean the arrangement of soldiers for battle, one of the skills which made up strategy, meaning generalship more broadly. By the end of the 6th century, these words took on more precise definitions: tactics referred specifically to the art of forming a single battleline, while strategy was the art of disposing and employing the entire army; tactics and strategy were comparable concepts, differentiated only by scale. Thus we see two separate traditions at the opposite ends of antiquity: the classical and the proto-Byzantine. Both would influence modern thought.

This influence was long in coming, however. For all that the men of the Renaissance looked to the classics for inspiration, they were far more influenced by Latin works than by Greek. The practical-minded Romans never took to such abstractions as tactics and strategy, even if several Latin texts used these words in their titles. Vegetius and Frontinus, the two ancient military authors who were read continuously in the West through the Middle Ages, only made passing reference to them. The one Greek word that did enter common usage was stratagem—the title of Frontinus’ work was Strategemata—which came to mean a ruse or trick.

Into the Modern Era

It was not until the 17th century, when Greek learning became more widespread in the West, that tactics was once again used for the arrangement of troops for battle. But it was rarely used for contemporary warfare—a dictionary from 1694 noted that the word was only used to speak of the ancients.1 It was not until the 18th century that a series of French officers, several of whom were skilled classicists, introduced tactics and strategy into modern language.

The first to apply the concept of tactics to contemporary warfare was Jean-Charles de Folard, who in 1724 published a commentary on Polybius. In it, he argued for interspersing the extended linear formations of his own day with shock columns of pikemen on the model of the Macedonians. His ideas failed to catch on, however, and the musty scent of antiquarianism clung to tactics for the next several decades.2

In 1755, Folard’s ideas were revived by François-Jean de Mesnil-Durand in his Projet d'un ordre français en tactique, which used the word tactics to describe various formations and advocated using a deep column in the attack. It was a fortuitous moment: just one year after Mesnil-Durand’s work was published, the Seven Years’ War engulfed Europe, sparking a lively debate around his ideas. Tactics became the new buzzword, the subject of several works which argued either for deep formations or extended lines. The debate very much followed classical notions of tactics, both in the specific formations and the conceptual framework.

The Precursors to Strategy

The concept of strategy took longer to develop. And when the word eventually entered common usage, it meant something very different from either the classical notion generalship or the proto-Byzantine notion of the conduct of battle. This owed to the mutual influence of two Frenchmen, who each introduced a novel concept of his own.

The first of these was Paul-Gédéon Joly de Maïzeroy, an accomplished Hellenist who had served under the legendary Maurice de Saxe in his campaigns of the 1740s. Maïzeroy introduced the concept of dialectics in his 1767 Treatise on Tactics, defining it as “encompassing the art of forming the plans for a campaign, and conducting its operations.”3 Dialectics could also extend far beyond the operations of a single army, to include the supporting actions of armies on adjacent fronts, or even the operations of allies in entirely different theaters.

This sounds a lot like the modern definition of strategy, which encompasses the entire war and is the ultimate responsibility of the head-of-state. Indeed, Maïzeroy adds: “The system of these great operations is always formed at court under the supervision of the prince; or at least generals only undertake them after having communicated their views and received his orders.”4 Maïzeroy’s expansive concept, which extended from the maneuvers of individual armies to the entire war, thus represents the first explicit identification of a realm of warfare entirely separate from battle.

The second important innovator was Jacques-Antoine-Hippolyte de Guibert, the most important advocate for reform following France’s defeat in the Seven Years’ War. Between 1770 and 1772 he published a two-volume essay on tactics which popularized the concept of grand tactics. The term had previously been defined by M. Bouchaud de Bussy in his 1757 translation of Aelian’s 2nd-century tactical manual. In the preface, he distinguishes grand tactics from elementary tactics: where elementary tactics is concerned with arranging individual units in standardized formations, grand tactics arranges the entire army according to the terrain. This applied not just to battle, but to marches and encampments.

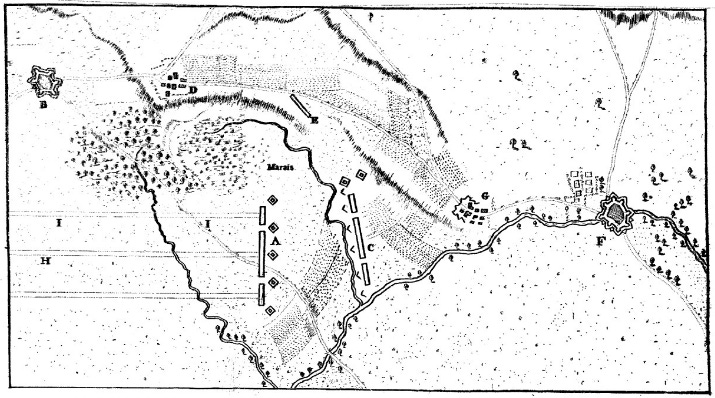

Guibert elaborated Bussy’s notion of grand tactics, calling it the science of generals: “just as elementary tactics has for its object to move a regiment in all the circumstances that war might offer, grand tactics has as its object to move an army according to all possibilities.” This naturally encompassed combined arms, arranging units of infantry, cavalry, and artillery to best effect. Guibert was especially interested in the march, demonstrating how many campaigns were won by a rapid march to a decisive point (for an illustration of one of his examples, see this thread on Denain).

This has led some to describe Guibert’s grand tactics as a prototypical operational level of war. That is a mistake, however: his entire focus is on how to conduct rapid marches to a decisive point, not on where to march. In particular, he advocated what he called the march-maneuver, moving the entire army in multiple parallel columns when the enemy is nearby. Not only does this allow the army to move much faster, but by arranging the columns in proper order, they can individually deploy against enemy detachments along the route and then rapidly deploy as a combined force once they reach the intended battlefield.

Taken together, Guibert’s notions of elementary and grand tactics recall what Xenophon wrote of Cyrus the Great:

He believed also that tactics did not consist solely in being able easily to extend one's line or increase its depth, or to change it from a long column into a phalanx, or without error to change the front by a counter march according as the enemy came up on the right or the left or behind; but he considered it also a part of good tactics to break up one's army into several divisions whenever occasion demanded, and to place each division, too, where it would do the most good, and to make speed when it was necessary to reach a place before the enemy.5

At the same time, his concept of grand tactics, as something that exists both within battle and on the march, is not far from the Strategikon’s definition of strategy.

The Byzantine Inheritance

The Strategikon did indeed shape 18th-century debates, albeit not directly. It was very influential on later Byzantine military tradition: the scholar-emperor Leo VI borrowed large sections for his Taktika, written around the year 900, including the distinction between strategy and tactics. This work drew the interest of many scholars in the 16th and 17th centuries, some of whom translated it into Latin.

In 1771, Maïzeroy published the first vernacular translation of the Taktika. This also marked the first modern use of the word strategy. Although Maïzeroy never used the word in the text itself—he always substituted some reference to the art of the general or of command—he used both strategy (stratégie) and strategics (stratégique) in his commentary.6 He defined strategics as “the art of commanding and of skillfully employing the means he has available, moving all his subordinate units and disposing them for success.” For strategy, he quoted Maurice’s definition directly: “Strategy makes use of times and places, surprises and various tricks to outwit the enemy with the idea of achieving its objectives even without pitched battle.”7 This more limited concept, with its emphasis on trickery, would have been intuitive for an audience familiar with the term stratagem.

Yet neither of these was the definition that stuck. By the time Maïzeroy published his Theory of War in 1777, his third important work, Guibert’s concept of grand tactics had firmly taken hold. Because it closely matched the Byzantine understanding of strategy, it displaced “strategics” from its natural conceptual box. Maïzeroy responded by elevating strategics, equating it to his earlier concept of dialectics, something existing outside the ambit of battle. He accordingly divided the science of war into three parts: elementary tactics, grand tactics, and dialectics/strategics.

Dialectics as it appeared in the Theory of War was not the broad concept he had envisaged a decade before, however. Maïzeroy’s focus was entirely on the movements of armies on campaign, highlighting the importance of time and distance. He illustrated this with examples from past campaigns, showing how generals tried to outfox each other by seizing river crossings, cutting off each other’s lines of march, or launching surprise attacks against undefended objectives. Strategics influence grand tactics, as armies must adopt different orders of march depending on the relative position of the enemy.

The German Innovation

If it was the French who elevated strategy above the level of battle itself, it was the Germans who popularized this new meaning. Between 1777 and 1781, an officer serving in the Austrian army named Johann von Bourscheid published his own translation of the Taktika for a German-speaking audience. This work translated Leo’s στρατηγική as Strategie, or strategy, which thereafter became the preferred term in all European languages.

Bourscheid followed this in 1782 with his Course on Tactics and Logistics, in which he discussed the relationship between grand tactics and strategy. He insisted on a sharp distinction between grand tactics and campaigning, reasoning that the two were each governed by a different logic:

maneuvering [in the immediate presence of the enemy] and operating [i.e. campaigning] have two different theories, each of which has its own calculations. Those of the former are tactics, those of the latter are the art of campaigning.

He then added, incorrectly, that “the art of campaigning was given the name strategy by the ancient Greeks”—this likely reflected more the influence of Maïzeroy than any Greek author.8

It was this definition that stuck. Although the word took some time to catch on—some German writers even took strategy to mean a kind of tactics9—an influential work in 1799 helped cement Bourscheid’s meaning. The Spirit of the New Military System by Dietrich Heinrich von Bülow (brother of the Prussian general Friedrich Wilhelm) defined as tactical everything that occurred within the maximum range of the heaviest artillery, and strategic everything that occurred outside it.10 This was a more limited definition of tactics than any previous author had envisaged—Guibert’s march-maneuvers certainly took place outside cannon range—but it firmly established battle as the realm of tactics and campaigns as the realm of strategy.

This was reinforced by Archduke Charles of Austria, one of Napoleon’s more skillful opponents, who referred to Bülow’s definitions of strategy and tactics in his 1806 Principles of the Art of War for Generals. The definitions he gave in his 1813 Principles of Strategy were more abstract, but their usage was consistent with earlier definitions:

Strategy determines the decisive points which must be occupied for an intended purpose and defines the lines to connect them……Tactics teaches how troops are positioned at strategic points, how they are used or directed there, and how they are moved along these lines to accomplish the strategic objective.11

This recalls Maïzeroy’s geometrical approach to campaign plans, including the relationship between strategics and grand tactics.

It was Charles’ Principles which influenced French writers of the 19th century, among whom the word had fallen out of favor. Jomini eventually settled on the definition of “the art of effectively directing masses in the theater of war.”12 He in turn influenced the British and Americans. The authoritative English-language text on strategy, Edward Bruce Hamley’s The Operations of War, stated: “The Theater of War is the province of Strategy—the Field of Battle is the province of Tactics.”13 Thus, throughout the 19th century, “strategy” meant what we now call operational art.

There was one exception, however. Although Clausewitz’ On War used the word in much the same way as his contemporaries, he defined it somewhat differently. This subtle shift eventually changed how we understand strategy, and ultimately led to the concept of the operational level of war. We will look at this in Part 3 on the levels of warfare.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Another work on military organization was published in 1740 under the title Tactics, but the word hardly appeared in the text—to the extent that it did, it described the different tactical paradigms that appeared through the ages.

Traité de tactique, p. 35.

Ibid, p. 36.

Xen. Cyrop. 8.5.15.

Where Maurice used the nouns τάξις and στρατηγία for tactics and strategy, Leo preferred the substantives τακτική and στρατηγική—hence Maïzeroy’s use of “strategics”, of analogous form to “tactics”. It is only an accident of history that “strategy” won out as the preferred usage. Intriguingly, “strategics” appears in modern languages at least twice before: in a 1646 history (p. 412), which includes it as one of the fields of knowledge, and intriguingly in a 1648 French abridgement of Matthias Dogen’s work on military architecture. A gloss states: “The art of war is composed of 3 parts: strategics, tactics, and poliorcetics [siegecraft]” (p. 465).

Kurs der Taktik und der Logistik, p. 10. Bourscheid evidently did not know much Greek, relying on a 16th-century Latin translation for his German translation.

In his 1787 Reine Taktik der Infanterie, Cavallerie, und Artillerie, the Württemberger officer Franz Miller made little use of the word strategy, vaguely stating that some elements of strategy did not seem to be described by tactics (vol. 1, p. 4). The future Prussian reformer Scharnhorst apparently misinterpreted this in his 1790 Handbuch für Offiziere, where his single mention of strategy asserted that it was a kind of tactics (vol. 3, p. i). Georg Venturini, creator of one of the first military boardgames, stated more confusingly that strategy and “the art of war” constituted the two parts of “applied tactics” (vol. 2.1, p. vi).

Geist des neuern Kriegssytems, p. 83-84.

Grundsätze der Strategie, p. 3-4.

Précis de l’art de la guerre, p. 36.

The Operations of War, p. 59.