The Levels of Warfare, Part 3: Operational Art

As we saw in Part 2, strategy and tactics had acquired more-or-less established meanings by the start of the 19th century. Military writers used tactics to refer to actions in battle, strategy to refer to the large-scale maneuvers of a campaign—a simple two-part division of all warfare. Through the course of the century, these definitions were adopted from French and German into all other European languages.

The one notable exception was Carl von Clausewitz. Although he used the word “strategy” much the same as his contemporaries, his precise formulation was different: “Strategy is the use of the engagement for the object of the war. [emphasis mine]”1 This was a radical departure: Clausewitz elevated strategy from the realm of the campaign to the entire war.2

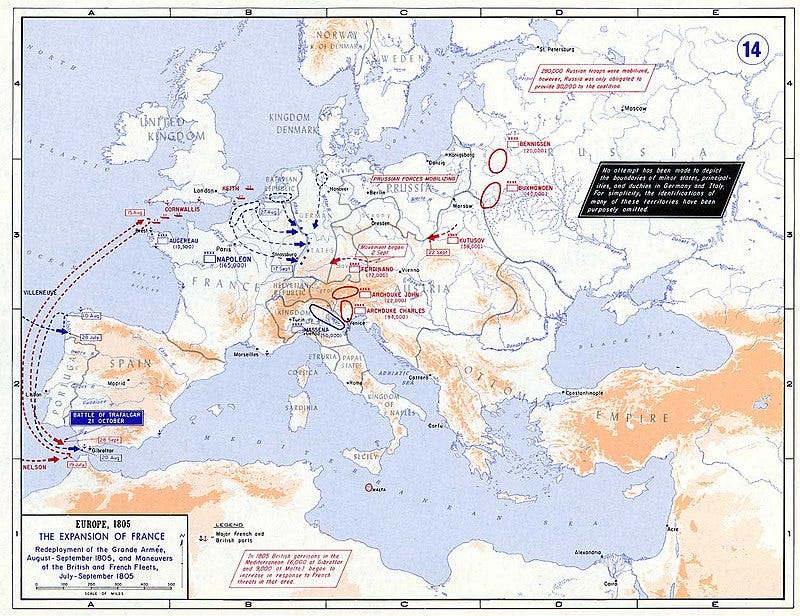

For all immediate purposes, the two definitions were the same. Clausewitz was writing in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, which were characterized by rapid, decisive campaigns in a single theater. Napoleon shocked Europe by winning the War of the First Coalition, which had been raging for four years, with an impetuous drive across Italy. He defeated the Second Coalition with another Italian campaign in 1800, then fought decisive campaigns in Austria in 1805, Germany in 1806, East Prussia in 1807, and Austria again in 1809. Even his much larger war against Russia and the Sixth Coalition consisted of three decisive campaigns in three successive theaters: 1812 in Russia, 1813 in Germany, and 1814 in France.

Nor did this change in the 19th century. All wars between major European powers were either wars of a single decisive campaign (the Second and Third Wars of Italian Independence, the Wars of German Unification), or at least successive campaigns in a single primary theater (the First War of Italian Independence, the Crimean War). It was not until the 20th century that Europe would see a return to the multi-year, multi-theater coalitional wars that had dominated the continent before the French Revolution.

The Gap Widens

Elsewhere, this pattern was already changing. Around the same time as the wars of Italian and German unification, the United States became engulfed in a four-year conflict that defied the European pattern. The Civil War was fought over a vast area, waged on both sides through mutually-supporting efforts in several theaters. There was no question of a straightforward relationship between individual battles and the ultimate outcome of the war. Even the Union’s final string of victories in Virginia depended indirectly on Sherman’s success in the Deep South and the maritime blockade. Clausewitz’ definition of strategy was insufficient.

American officers were not disciples of Clausewitz, however, but of Jomini. The latter, in his 1836 Summary of the Art of War, divided warfare into six parts: the purely military—strategy, grand tactics, logistics, engineering, and elementary tactics—and another that he called war policy.3 War policy was the state’s overall plan for war, determined by a combination of military and political factors; the part specifically concerned with the use of armed force was called military policy.

Although Jomini did not conceive of these as “levels of warfare”, his definitions of military policy, strategy, and grand tactics correspond very closely to our modern notions of strategy, operations, and tactics. This was also consistent with 18th-century views, which saw military action as only one part of war. The Marquis de Silva, a Portuguese nobleman who served in several armies across Europe, wrote in 1778: “The general war plan involves two types of objectives. The first is determined by policy, the other depends immediately and totally on military science.”4 He then goes on to describe how in peacetime, monarchs, ministers, and generals should devise campaign plans for different potential war aims.

Clausewitz’ definition of strategy also had precedents, even if these were not as radical. Ferdinand Friedrich von Nicolai was a German general and military reformer who later became the head of Württemberg’s military academy. In 1781, he wrote the Regulations for a Common Military Academy for All Arms, in which he envisioned warfare as forming a continuous chain:

Elementary tactics tie the first links in this chain; grand tactics instructs how to hang them together in different ways, that is, to maneuver. Strategy seeks to apply them appropriately, that is, to operate, to tie operations to operations, and through regular sequencing of them, direct the course of the war to the desired results. [emphasis mine]5

There is a crucial difference between the two, however. Whereas Clausewitz defines strategy in relation to its highest purpose—namely, the war—Nicolai focuses on the means, building up to that purpose from the lowest level. And for this, he uses another crucial word: operations.

Operations in History

The word “operation” had long been used in a military sense. Since at least the 16th century, it could refer to anything an army did: marching, digging entrenchments, foraging, etc. The use of operations in the collective sense could also imply a specific design: not long after ”campaign” and “theater” entered the lexicon, it became common to speak of planning for the operations of the campaign in a given theater. Thus, already by the second half of the 17th century, operations were closely linked with what in the following century would be called strategy.

In 1781, a Welsh soldier named Henry Lloyd introduced the term line of operations in his Reflections on the General Principles of War. These were the lines along which armies operated, passing from their supply depots and fortresses in the rear up through their encampment and onward to the objective. The term became popular among writers such as Bülow, Archduke Charles, and Jomini, who elaborated a new vocabulary of strategy: bases of operations, operational theaters, strategic fronts, lines of communication (distinct from lines of operation, which are the principal lines of advance), etc.

By the end of the 19th century, German officers began using the term operational (operativ) to describe the coordination of several armies or corps along several independent lines of operation. This should also not be conflated with the multiple march columns of Guibert or Jomini’s grand tactics, which only separated to speed up movements, but reunited before battle. The sheer size of armies often made it impossible to consolidate in one place; “battles” were often a series of separate engagements fought by individual corps converging on the enemy. German military writers began explicitly contrasting operational decisions with both tactics and strategy.

This change was crystallized with World War I. The return of multi-year, multi-theater warfare shattered Clausewitz’ framework of strategy and tactics. Hugo von Freytag-Loringhoven, a general who served on the German General Staff, wrote after the war:

In the German army, starting with the General Staff, the word “strategic” has been used less and less. As a rule, we increasingly use “operational” to describe more simply and clearly the distinction with all that is called “tactical”. Everything operational takes place largely outside of combat itself, whereas the term “strategic” easily confuses things, as shown by the example of our opponents, who speak of strategic circumstances when discussing purely local matters. The word strategy should in any case be reserved for the army command’s greatest designs.6

Strategy, in the German understanding, had completed its evolution from the maneuvers of a campaign to the planning of the entire war effort.

The Soviet Innovation

Beginning in the 1920s, Soviet military theorists began developing their own concept of operational art (operativnoe iskusstvo) in response to their own recent experience. The Reds had triumphed in the Russian Civil War through the use of sweeping operational maneuvers, but had completely failed in their 1920 offensive against Poland. The Poles managed to hold the line of the Vistula River, a narrow front which allowed for a much greater density of forces. This led Soviet theorists such as Svechin, Tukhachevsky, and Isserson to begin studying the specific problems of the Western Front in World War I.

The origins of operational art have been the source of much confusion. It is sometimes described as a uniquely Soviet innovation or as reflecting a new level that only emerged with the complexity of modern warfare. Neither is of course true: operational was a German coinage, and it referred to what had once been called strategy. In apparent agreement with Freytag-Loringhoven, Svechin contrasted operational art with tactical art, meaning the orchestration of combined arms, and strategic art, which he defined in terms of the ultimate objective of the war.

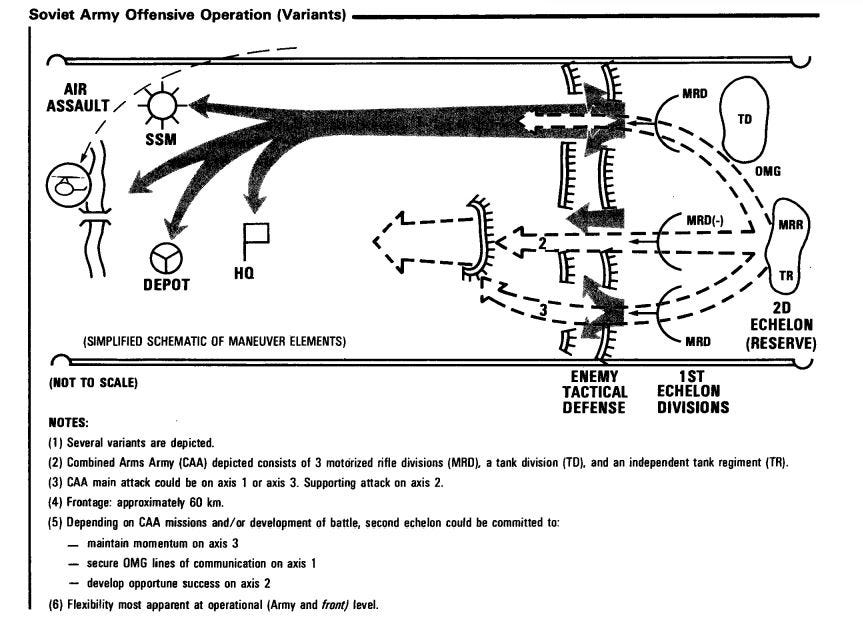

What was novel about operational art was not the “operational”, but the “art”. This referred to the careful sequencing and synchronization required to break through multiple defensive belts protected by machine guns, wire, and modern artillery. Soviet planners envisioned attacks in multiple echelons designed to fix the defenders in place, create a penetration at a certain point, then rush mobile forces through the gap into the rear areas. These were to be supported by airborne insertions, airstrikes, and elaborate deception plans.

This was a much greater challenge than the massive encirclements and penetrations which the Germans had previously called “operational method” (operative Verfahren, the likely inspiration for the term “operational art”). The open-country maneuvers of the Napoleonic era, the Franco-Prussian War, or the World War I Eastern Front were necessarily improvisations, executed in response to the enemy’s actions—hence Moltke’s famous dictum that “strategy [i.e. operations] is a system of expedients”. Operational art, by contrast, required detailed planning in advance of each offensive.

Shifting Definitions

Despite the enormous growth in size and complexity of armies, the Soviets’ paradigm remained essentially the same as what existed at the end of the 18th century—only the labels had changed. Compare the Marquis de Silva’s description of war planning above with Svechin’s definition of strategy:

Strategy is the art of combining preparations for war with the grouping of operations to attain the objective that the war sets for the armed forces. Strategy resolves questions relating to the use of the armed forces and of all the country’s resources to achieve the ultimate objective of the war.7

Strategy in the Soviet view was thus little different from Silva’s war planning or Jomini’s military policy, inseparable from political questions. Likewise, the operations of a campaign were always recognized as a separate domain, whether under the name “strategy” or “operational art”. The only change in the definition of “tactics” has been the disappearance of “grand tactics” as a subcategory.

Despite the stability of these concepts, the shifts in their labels have caused much confusion over the years—especially when the concept of operational art was adopted into English. That will be the subject of the final post in this series.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

On War, 3.1. In the same paragraph Clausewitz states: “The distinction between tactics and strategy is now almost universal, and everyone knows fairly well where each particular factor belongs without clearly understanding why.” The irony is that in trying to draw out the intuitive logic of the term, he inadvertently changed its definition.

Précis de l’art de guerre, p. 35-37.

Heerführung im Weltkriege, vol. 1, p. 46. Freytag-Loringhoven was one of those who took Jomini’s grand tactics to mean operations in the modern sense—the latter’s definition of “strategy” is so clearly a better fit, that it is likely he never read Jomini.

Great article! I was very surprised to learn about the influence of Jomini on 19th century American military leaders.