A War on Many Stages: Theater Strategies and the War of the Spanish Succession

On 1 November 1700, Charles II of Spain died without issue. He had long been suffering from an extended illness, and his last years were occupied with the question of succession. The two leading candidates were from the great rival houses of Europe: his Habsburg cousin Archduke Charles (son of Emperor Leopold of Austria) and his Bourbon nephew Philip of Anjou (grandson of Louis XIV of France). Philip ultimately won out, ending the longstanding antagonism between Spain and France. This drastically altered the balance of power in Europe, setting in motion a series of events that led to the longest and most destructive war in the reign of Louis XIV.

The War of the Spanish Succession, although the best known of Louis’ wars, is not widely studied in the anglophone world. Outside of a few military and diplomatic historians, it is known chiefly for the Duke of Marlborough’s feats of arms: his 400-km march from the Netherlands to the Danube, and his great victories at Blenheim and elsewhere. Yet these were just parts of a much larger picture. As with all the major wars of Louis XIV, this one consisted of many hard-fought campaigns conducted in several different theaters against a complex diplomatic backdrop.

Military strategy in these wars gets particularly short shrift. Whereas the key battles or campaigns can be studied with only a bit of background information, understanding the two sides’ strategies requires much more detail: the various actors and the relationships among them, their salient interests in each theater, and how events in one theater affected all the others. This shaped how the principal players sought to achieve their war aims, which theaters they emphasized from one campaign season to the next, and how their war aims changed over the course of the war. The relationship between individual theaters and the overall war effort is especially fascinating.

Theater Strategy

The term “theater of war” is an interesting one. It was had long been a poetic cliché used to describe the outbreak of war in a land (“Italy, which had once been the garden of peace and of earthly delights, was turned into a theater of war and an abode of desolation.”1). Under Louis’ reign, its meaning somewhat shifted: it was used by generals and statesmen to designate a specific area where a war would be fought (the older English term for this was “seat of war”).

I speculate elsewhere that this metaphor had a subtler meaning to contemporary ears. Theater was an obsession of the time, governed by a set of conventions known as the three neoclassical unities:

· Unity of place: a drama should be set in a single location

· Unity of time: it should transpire within the space of a single day

· Unity of action: it should consist of a single dramatic plot

Perhaps it is no coincidence that just around this time campaign also assumed a particular meaning, shifting from a one-off expedition to the duration of the fighting season—generally early spring to late autumn. Operation was another term that took on a particular meaning around this time: it was increasingly used in the plural to describe a coherent set of actions toward a certain end, particularly in the context of a campaign. The language of the stage thus informed discussions of strategy: the operations of the campaign in a particular theater encompassed unity of action, time, and place. And indeed, individual theaters usually were self-contained dramas at the operational level, defined by what could be directed by a single commanding general—unity of command was a corollary of the other unities.

But what role did these separate dramas play in the larger picture? War aims in the dynastic conflicts of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries were often grab-bags of desiderata, each theater representing separate objectives. Alliances were marriages of convenience, directed against a common enemy but lacking a comprehensive strategy—individual states prioritized theaters based on what was at stake in each. It was accordingly rare that wars were straightforwardly won or lost: more often, they ended with concessions in some areas and gains in others.

The wars of Louis XIV were partly guided by these dynamics, but they were also something more. The coalitions that formed against the Sun King were designed to curb his ambitions in Europe and prevent France from becoming an unchallenged hegemon, giving each participant an interest in seeing the larger effort succeed. This was especially true in the War of the Spanish Succession. The Grand Alliance that fought him was united by several shared objectives, while French and Spanish interests were completely intertwined throughout the course of the war.

The sprawling conflict lasted twelve years, from the Grand Alliance’s declaration of war in 1702 to the final peace between France and Austria in 1714 (although the actual fighting started earlier and lasted longer). The war can be divided into two phases. The first decided whether Philip of Anjou would inherit all Spanish possessions in Europe, and was concluded by the end of 1706. At that point Bourbon forces had been driven back on all fronts, raising the next question: whether Philip would be allowed to keep even the crown of Spain, and whether that decision would be imposed by force.

The first phase is more interesting from the perspective of strategy. Each theater was not only an objective in its own right, but played an important role in the larger conduct of the war. Operations in one could open up new possibilities in another, and individual countries could satisfy their ambitions indirectly through victories on distant battlefields. Forces could be shifted from one to another within a single campaign season, and operations could be stitched together across the entire map to achieve much larger effects. The two sides’ strategies were an intricate dance, played out over a vast area.

The War for Europe

It was obvious to most observers at the beginning of 1701 that Europe was perched on the brink of war, but the full extent was not yet evident. Austria was the only country implacably opposed to the current arrangement. She not only maintained her own candidate to the Spanish throne, but refused to accept a Bourbon presence in northern Italy, which threatened her southern boundary; the loss of Flanders and Spain to the Habsburg cause moreover deprived her of offensive weapons against the French.

Austria’s main allies from the previous war had been England and Holland. The Dutch Stadtholder, William of Orange, was crowned William III of England in 1689, effectively uniting those two countries’ foreign policies. He had no intrinsic objection to Bourbon accession to the Spanish throne, and warily eyed developments. Austria alone prepared for war.

At this point, Louis made several mistakes. His first was to affirm Philip’s place in the French order of succession. Although Philip was only third in line, and a number of provisions ensured that Spanish territory could not be transferred to France, this raised the maritime powers’ hackles. Then Spain gave French merchants a monopoly on the slave trade in the New World, threatening the maritime countries’ commercial interests. A more serious mistake came in February 1701, when Louis ordered French troops to join the Spanish in occupying fortresses in the Low Countries and northern Italy. They expelled the Dutch garrisons from the “Barrier Fortresses”, a chain of fortifications in the Spanish Netherlands they had previously been allowed to occupy as a security guarantee for their southern border.

Whether this was done out of sheer arrogance or an abundance of caution, it put the Dutch in an intolerable position. It also threatened England, as the Flemish coast and Scheldt estuary could be used as a base to blockade the Channel. When French diplomats proved intransigent, William began negotiating with Austria to resurrect the Grand Alliance which had bound the three powers against France during the Nine Years’ War.

Austria, in the meantime, opened hostilities without a formal declaration of war. An army under the talented field marshal Eugene of Savoy descended on northern Italy in May, cutting through Venetian territory to turn the Bourbon army’s flank and force them to fall back over 100 km.

This early success emboldened England and Holland, who on 7 September signed the Treaty of the Hague. The confederates of this new Grand Alliance agreed that:

1. They must receive binding guarantees that the crowns of France and Spain would remain separate.

2. Austria would receive all of Spain’s territories in Italy, the Low Countries, and the Balearics.

3. Holland would regain the Barrier Fortresses.

4. The Elector of Brandenburg would be promoted to King in return for support to the Allies.

5. Imperial states that provided support would receive financial subsidies from the English and Dutch.

6. England and Holland should keep their old commercial privileges with Spain.

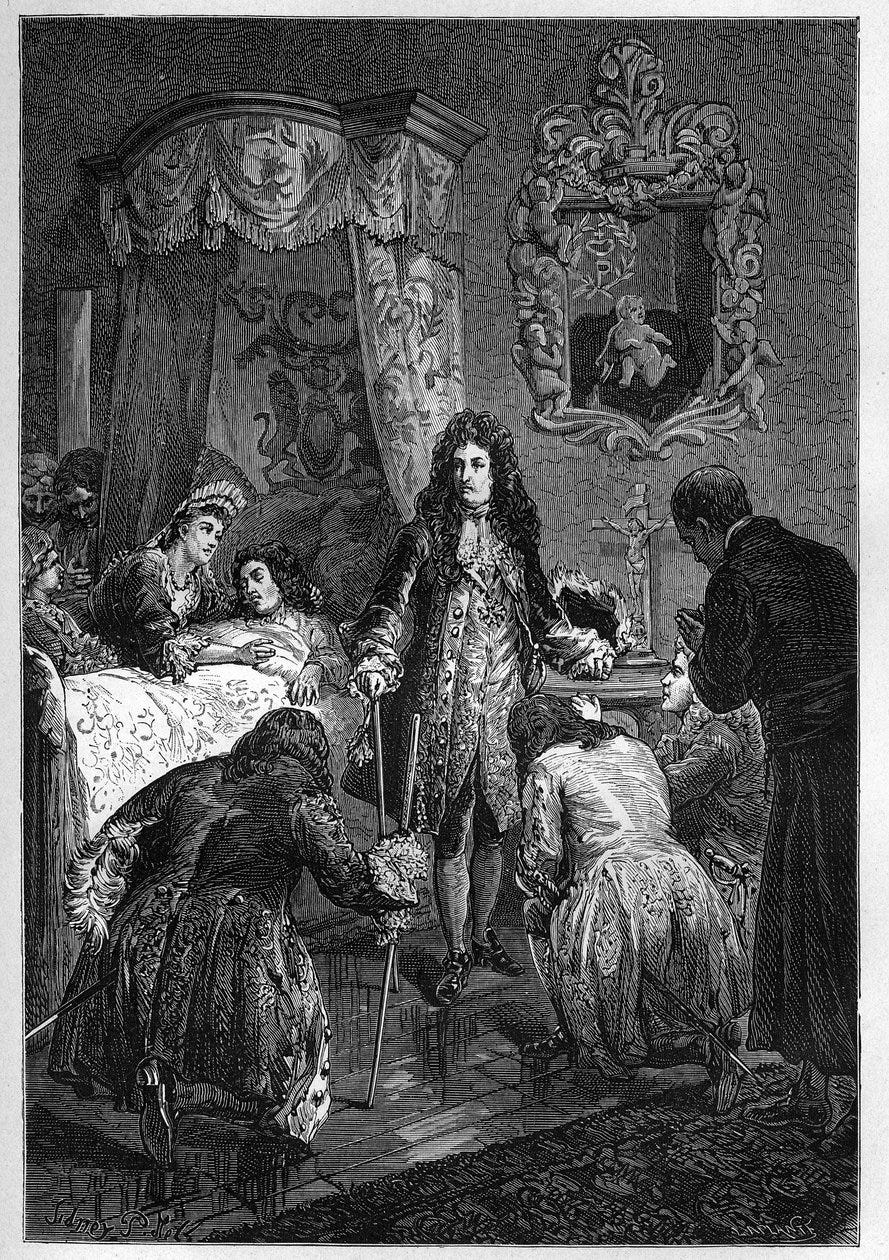

The French learned of the treaty just days after it was signed. England and Holland had still not fully committed to hostilities and war was perhaps still avoidable, but at this point Louis committed a final indiscretion. James II of England, who had lost his throne to William III in the Glorious Revolution, had been living in exile with his fellow Catholic at Versailles. As he lay dying that September, a choked-up Louis promised that he would acknowledge James’ son as King of England. The erstwhile monarch expired on 16 September and Louis proved true to his word, proclaiming his son James III, King of England.

Whether this was a purely symbolic gesture for an old friend, as French diplomats protested, or something more serious, it directly violated the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick. Louis had supported Jacobite uprisings in Ireland and Scotland during the recent Nine Years’ War, and England considered recognition of William’s legitimacy a key guarantee of her security. Louis’ blithe dismissal of these concerns destroyed any remaining belief in his good faith. Over the winter of 1701-02, the Grand Alliance prepared for war.

The Strategic Picture

The Bourbons had secured several allies of their own, chief of which were Portugal, Savoy, and Bavaria. The first two were important for closing potential invasion routes: Portugal shut the Allies out of the Iberian Peninsula, while Savoy controlled the Alpine passes along France’s southeastern border (and eased the passage of French troops into Italy). Bavaria, on the other hand, offered them a potential invasion route into Austria.

Several minor German princes also pledged to support the Bourbon cause. Most important of these was the Elector of Bavaria’s brother, who was both Archbishop of Cologne and Bishop of Liège. This gave them a contiguous strip through Spain’s northern territories (the Spanish Netherlands, Upper Guelderland, and Luxembourg) to the lower Rhine.

This left a long, if disjointed, frontier between the two coalitions. Although both had sufficient manpower to field armies in all theaters (the principal Allies alone pledged to mobilize a total of 232,000 men in 1702), these varied considerably in strategic value. Before looking at the two sides’ war plans, it is worth a brief detour to examine the individual theaters.

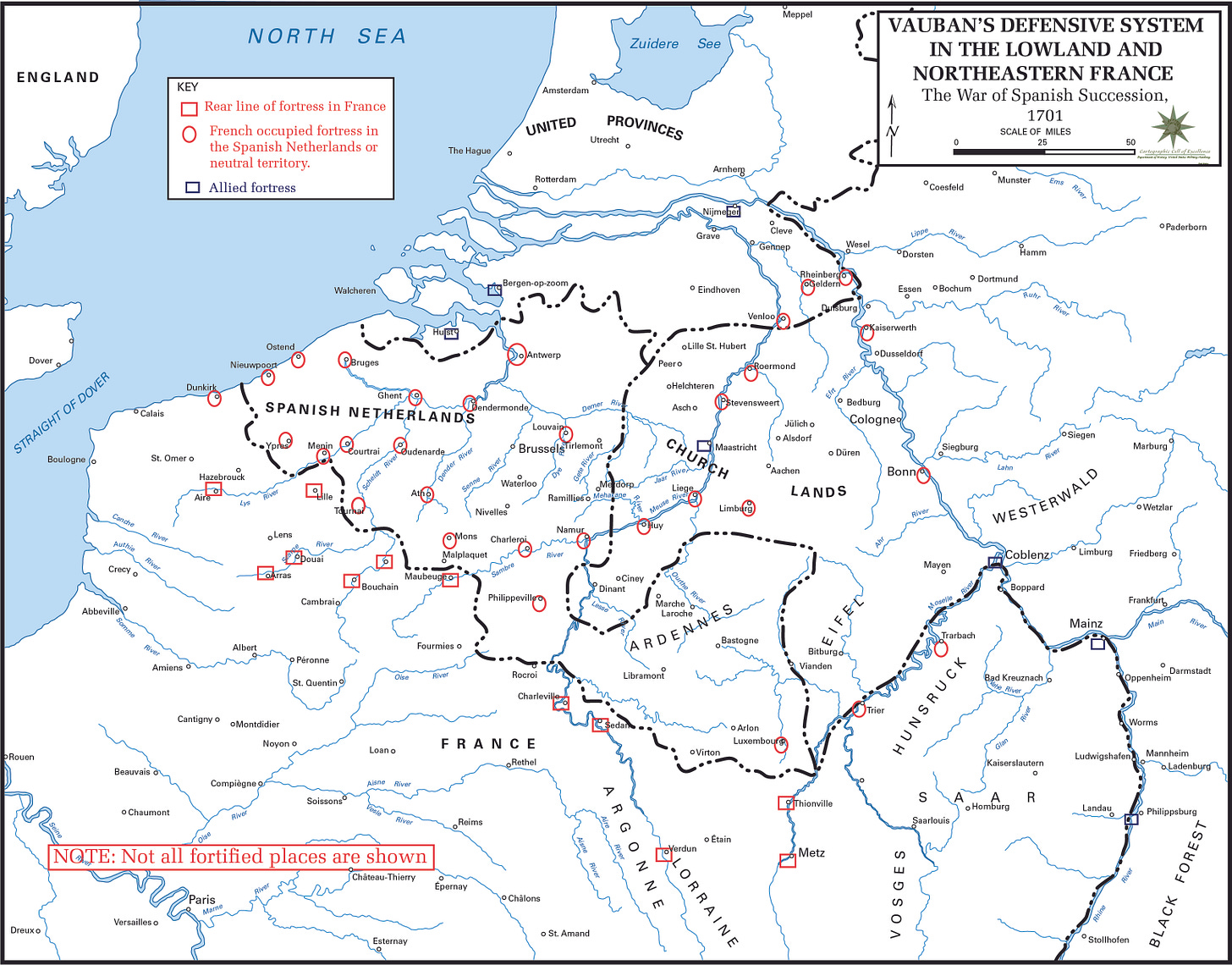

Low Countries/Lower Rhine

The Spanish Netherlands were bounded by the sea to the northwest and the River Meuse to the southeast, beyond which lay the difficult country of the Ardennes. This flat, open terrain had made it a major invasion route into northern France since the 13th century, when an Imperial army first leagued with the English against the French crown.2 The region’s rich farmland could moreover sustain large armies, and was cut through with many waterways that could be used to move supplies.

This paradoxically made it one of the most heavily fortified regions in Europe. France’s two-century rivalry with Spain had led to extensive fortress construction along the southern border, while the long Dutch Revolt (1568-1648) led to the same in the north. In 1701, French and Spanish soldiers began constructing massive fortified lines to complement the existing defenses. The Lines of Brabant stretched 125 km from Antwerp to the Meuse near Namur, defending the main approaches, while the Lines of Flanders covered 85 km along the Dutch enclaves west of the Scheldt.

These lines consisted of ditches, ramparts, and bastions, connecting the many forts that dotted the region and integrating dykes and watercourses. Although they could not be manned along their entire length, they could be occupied as needed to defend a certain area, and smaller corps could fight holding actions until reinforcements arrived.

In the context of the War of the Spanish Succession, this theater extended all the way to the lower Rhine. The countryside between there and the Lines of Brabant was open and flat, allowing rapid communications and movements of troops. Although the width of the entire area from the English Channel to the Rhine was nearly 250 km, requiring a broad dispersion of forces, both sides placed it under a single overall commander

The Rhine

If the Low Countries were the natural invasion route into France, then the upper Rhine was the highway into Germany. The broad valley is about 40 km wide in most places, bounded by the Vosges on the west side and the mountainous Black Forest to the west. Alsace (the left bank) and its capital Strasbourg were some of Louis’ most important conquests of the 1670s and 80s, as they gave him a way to directly threaten the Imperial states. His armies could march north and threaten the many principalities along the lower courses of the river, or turn east around Karlsruhe and strike deeper into Germany. To protect against this threat, the Imperials built three defensive lines of their own: one blocking the route north along the left bank, by Speyer; another on the right bank 70 km south, around Stollhofen; and a third running north-south through the Black Forest.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.