Attrition and Victory: Prospects for the Offense in an Age of Defense

One of the irresistible temptations of military history is to imagine counterfactuals in which the losers triumph against the odds. Especially when the weaker side demonstrates tactical or operational brilliance: Hannibal against Rome, Napoleon in Russia, the Confederacy in the American Civil War, the Wehrmacht on the Eastern Front.

These imagined victories always follow a very narrow path, seizing on opportunities that were not necessarily foreseeable or prudent at the time. What if Hannibal had marched straight to Rome after Cannae? Or if Napoleon committed the Guard in the last hours of Borodino? Could better logistical organization, higher muzzle velocities on the Panzers, or outreach to Ukrainian nationalist groups have swung the outcome of Operation Barbarossa?1

Whether or not any of these factors might have made a difference, counterfactuals underscore how narrow the path to victory is for the weaker side. One can just as easily flip things around to show how the stronger power could have won much quicker. If the French had not prematurely moved their reserves into Belgium, the Allies could have blunted the German thrust through the Ardennes. With better organization and more decisive leadership in the Peninsula Campaign of 1862, the Union could have broken through to Richmond. The stronger side can afford not only more throws of the dice, but to endure the cost of its failures.

Victory by Attrition

This asymmetry reflects an enduring fact of warfare: unless a war is won quickly through a series of battlefield victories, it is almost always the stronger side that comes out on top. That is to say, most wars are won or lost through attrition: no matter how good an army’s performance on the battlefield, it is usually the relative balance of casualties, equipment loss, and expense that decides the ultimate outcome.

This is true despite the fact that battlefield outcomes are almost always the proximate cause of one side’s defeat. It was the Allies’ battlefield successes, not the total butcher’s bill, which compelled Germany to accept the Armistice in 1918. The Allies broke through two major defensive lines that autumn and by early November looked poised to make a clean break through a third, opening the way into Germany itself—the previous four years of attrition were important insofar as they allowed the rapid gains of the Hundred Days.

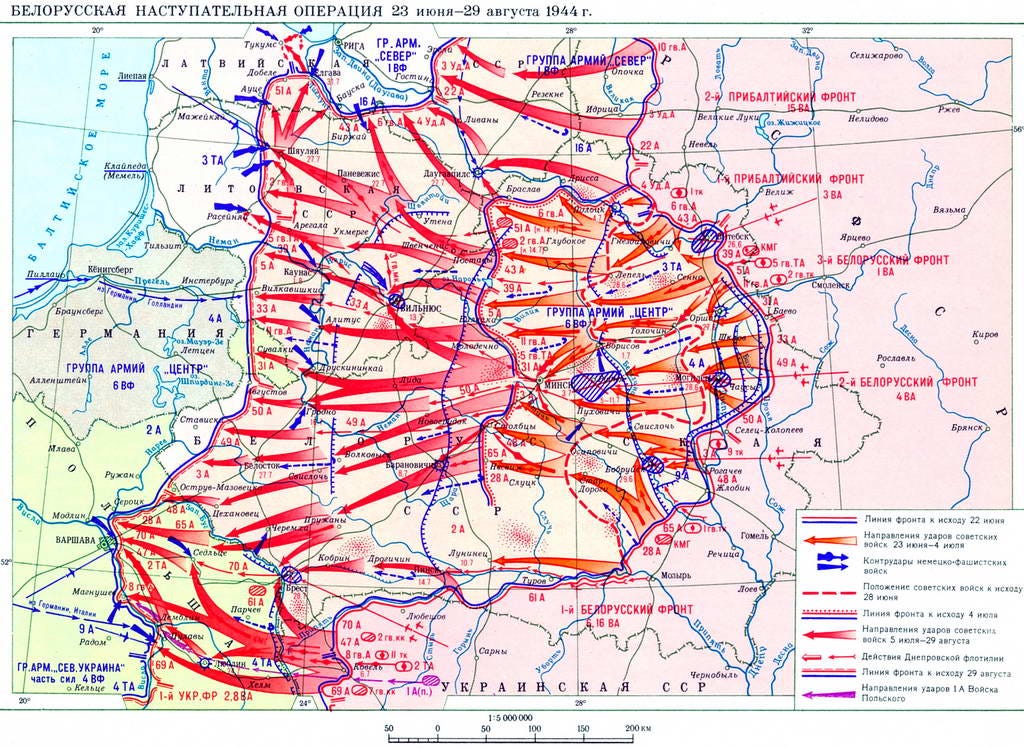

The same can be said for the great Soviet offensives that won World War II on the Eastern Front. The Red Army had steadily been growing in size and improving in quality up to 1943, leading to Soviet victories such as Dnieper, Bagration, and Vistula-Oder. Yet the German armies swept aside by these hammer blows were husks of what they had been. They had few experienced personnel, tanks, or airplanes remaining, and fuel shortages limited their use of the vehicles they did have; the Allies’ strategic bombing compounded these losses.

Ambiguous Cases

Large, protracted wars are obviously attritional. It is very rare that one side or another manages a military victory late in a war against an enemy that has not been seriously degraded by attrition (the War of the First Coalition, won by Napoleon’s drive across northern Italy toward Vienna against superior Austrian forces, is the only example of the past few centuries that immediately springs to mind).

The balance between the two is far more ambiguous in smaller and shorter wars, such as Second Nagorno-Karabakh. The war ended when Azerbaijani forces managed to sever the key artery linking Artsakh to Armenia, a clearcut battlefield victory. Yet this was after Azerbaijani TB-2s had spent weeks knocking out Armenian air defenses and armor—about half their tanks were destroyed or captured, the majority by drone. It is hard to say whether a better-organized Armenia could have shifted forces to block the Azerbaijani axis of advance, or if the overall destruction of its ground forces left it simply out of options.

The very nature of smaller wars blurs these lines. Azerbaijani drone strikes were completely novel, leaving little time for the Armenians to adapt tactics in the five-week war. The defenders lacked the strategic depth or reserves that might allow a larger power to reach an equilibrium. It could be said in this case that the scale of the theater was so small that there was no practical difference between attrition and the preparatory stages of the ground offensive.

Choosing the Defeat Mechanism

In larger wars, however, the choice between an early victory and attrition poses a dilemma for the war planner. This brings us back to the premise raised in two previous pieces, that the chaotic early conditions which offer the chance for a rapid victory will quickly give way to a much more difficult struggle along solidified lines. Is it therefore better to aim for a sharp campaign that knocks the enemy out of the war at the start? Or does this risk making the inevitable attritional phase even harder and more protracted?

Russia learned the price of early failure in Ukraine. Many of its best units were mauled in the first month, putting it in markedly worse shape for the subsequent war of attrition. Yet that is not to say that attacking powers are more eager to attempt an attritional approach from the outset. One of the few exceptions was Desert Storm, where coalition air power destroyed about 40% of Iraqi tanks and nearly half the artillery by the time ground forces crossed the line of departure—a rare case where the technological edge was so great that an attritional strategy could win at the cost of minimal casualties.2

In most cases, even a much stronger power does not enjoy such an advantage. The promise of a long attritional slugging match is by itself a strong deterrent to war. If the proliferation of precision munitions makes mobile warfare difficult, but they are still scarce enough that attackers cannot amass sufficient numbers for a breakthrough, then the window is very narrow in which an aggressor can snatch a substantial victory against a near-peer adversary.

Planning for Future War

At present, Ukraine is our only example for envisioning how modern weapons might be used between near-peers. Its geography is fairly unique: it shares an unusually long land border with Russia, but also possesses enormous strategic depth, and the maritime component plays relatively little role. This leaves open a vast number of potential conflicts where it is harder for a full-scale invasion to succeed, but where more limited strategic objectives are more readily attainable.

To name three plausible (if not necessarily likely) scenarios: Chinese occupation of the Himalayan watersheds on the Indian side of the LOAC, destruction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam by Egyptian and Sudanese forces, or Azerbaijani occupation of the remainder of Artsakh. Each of these would likely face cross-border retaliation or perhaps even a protracted low-level conflict, but any serious counteroffensive would have even worse odds than the initial invasion.

This makes limited wars more likely: so long as an attacker can amass sufficient force to achieve initial objectives, it can reasonably hope to hold onto its gains. Second Nagorno-Karabakh, standing ambiguously between a small-scale war of attrition and a short war of decision, probably represents the upper limit of what can be expected from such an operation. It is also a good illustration of the potential difficulties, with a larger and better-equipped army fighting through difficult terrain.

The recent shift of the balance to the defense’s favor does not eliminate the prospect of the offense, it only changes the potential dynamics. The thing to watch now is how militaries adapt their technology and doctrine to exploit these opportunities.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Hermann Balck, a Panzer general on the Eastern Front, summarizes the problem of counterfactuals well: “Deliberations about whether various operational decisions could have led to success may be rather interesting, but they also are a sure sign that the force had been expended and the culminating point of victory had been surpassed. The indicators of a healthy, promising operation are the ability of the available, participating forces to resolve tactical and operational errors and personnel glitches. Such errors are then not apparent and can be ignored.” Order in Chaos, p. 231.

This is not to say that he saw an invasion of Russia as fundamentally unwinnable: in the following paragraphs, he raises the possibility that longer barrel lengths might have made a decisive difference at the Battle of Moscow, and identifies inadequate industrial policy as a key part of the German defeat.

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-NSIAD-97-134/html/GAOREPORTS-NSIAD-97-134.htm

Very good point about the use of counterfactuals. Sometimes there are historical documents from the warring parties' plans that didn't come to fruition that can help us assess the counterfactuals better.

Why a war is won can be alot more complicated than you suggest. The Kiel mutiny, for example, may have played a larger part in the ending of WW1, as may the relative roles of the atom bomb and the Soviet declaration of war in the Emperor's decision to enter his Cabinet's decision-making ending the War in the Pacific. These are counterfactuals of sorts which are decisive depending on the emphasis you give them. To Hitler, Ludendorff, Hindenburg and very many in Weimar Germany, for example, the Army's defeat was a counterfactual, it had been stabbed in the back by German communists, social democrats and Jews.

Finally, although your title didn't eventually get transmitted into your excellent content, WW1 was held to have proven the superiority of the defensive, and yet the war in the Middle East between Britain and the Ottoman Empire was entirely one of manoeuvre. Had it been one of attrition, either Britain would have withdrawn and thus lost, needing its resources to face the Imperial German Army in Europe, in which case the Ottoman Empire would have stood and the current Arab-Israeli conflict would never have happened. Or Britain would have won a war of attrition and so prevented the upstart Turkey from committing genocide and being the nuisance it was in the postwar period (and has been ever since?).

Did Russian units really get "mauled" in the early stages of the SMO? There were plenty of "claims" by sources that have been shown to lie constantly. The actual confirmed losses of these various units (for example the 155th Marine Brigade) are all tiny fractions of what the claims are. In fact, captured Ukrainian documents seem to indicate that the Ukes were losing 2 soldiers for every 1 Russian in the early days; a number that has gotten even worse for them as Russian artillery dominance becomes ever more pronounced.