Economics vs. Decision: The Two Logics of Warfare

There is plenty of overlap between economics and warfare. Last month we looked at how the theory of comparative advantage shapes weapons acquisition and tactics. Many books examine the economic forces that shape warfare: John Robb has written on the market dynamics of open-source insurgency, while Adam Tooze wrote the magnum opus on the Nazi war economy.

Medieval Arab writers sometimes used the marketplace itself as a poetic device to describe the crowded give-and-take of actual combat—one wrote of Richard the Lionheart’s advance down the coast during the Third Crusade: “Their troops continued to advance in close order while the market of war was densely thronged.”

Our own expression economy of force implies a need to properly allocate resources as a business might. Economic logic governs all aspects of warfare, and is part of the inspiration for the name of this account.

Yet warfare is also governed by another logic that runs directly contrary. That is the logic of decisiveness: concentrating all available force at a critical time and place; ignoring restraints and straining every nerve to achieve some final victory. This logic recognizes that it is better to lavish resources than to fall short of the objective. This is the logic expressed by Guderian’s saying Klotzen, nicht kleckern—hammer, don’t tap—or realized in the HE race of the infantryman.

It is not too much of a stretch to say that the tension between these two logics runs through all of warfare.

Attrition and Decision

The competing frameworks largely—but not entirely—align with attrition vs. decision. In a purely attritional contest, strategy can be reduced to an optimization problem: distributing forces to maximize loss ratios. Geographic objectives only count insofar as they can secure a favorable exchange, less the cost to take them. Likewise, in a war that can be decided in a single action, it makes sense to throw everything into the culminating engagement, to leave no reserve whatsoever.

In reality, the contrast is less dramatic. A French victory at Austerlitz was by no means guaranteed to be decisive, while the Germans had a hard time estimating loss ratios in a deliberately attritional battle such as Verdun. The fractal nature of warfare adds to this uncertainty: a crushing victory such as Cannae or Agincourt may be decisive within the scope of a single campaign, but have virtually no strategic impact beyond it.

The Cavalryman vs. the Logistician

Much also depends on the personality of the commander. It is the age-old clash of the cavalryman with the logistician, the field commander with the higher headquarters. Drive on to Egypt, as Rommel did, or secure the Mediterranean supply lines, as Kesselring would have preferred?

A leader like Napoleon favored decisiveness because he was confident that he could win critical battles in the most adverse conditions. Compare that to Louis XIV, who was far more cautious. Delicate court politics compelled him to give high commands to loyal favorites who sometimes made mediocre generals, and to curb the ambitions of his best marshals. He was also sensitive to the perennial vulnerability of France’s northern frontier, inclining him to a fortress strategy that did not lend itself to dramatic victories.

A version of this dilemma even exists at the grand strategic level, such as we see with the US-China rivalry. National power derives from economic strength, which in turn demands efficiency. Yet economic efficiency is an outright liability in strategic competition—something we see now with Western nations outsourcing their industrial bases to China. The uncertainty inherent to any contest is amplified by how much it hinges on the effects of not-yet-invented technology. The coordination problem is more difficult because long-term decisions must be made by planners who do not agree on the basic shape of the problem.

Caution on the Brink

Apprehending the dominating logic of a situation can be difficult; following it to its logical conclusion is another. So bold a commander as Napoleon exhibited great caution in the course of his greatest failure—his invasion of 1812. After failing to trap the Russians at Smolensk, he pressed on past his logistical support in pursuit of his decisive battle. When he finally got it at Borodino—his last chance to destroy the enemy army—he was surprisingly tentative. The emperor rejected Davout’s suggestion of a strong flank attack at the beginning of the battle, and refused to commit the Imperial Guard at the culminating point despite the urgent appeals of his generals, not wishing to risk his last reserve so far into enemy territory.

Whether or not those alternatives would have worked, Napoleon’s uncharacteristic caution guaranteed defeat. His supply situation was simply unworkable, ensuring that an unfavorable correlation of forces got even worse: when he next faced the Russians during the retreat, he was hopelessly outnumbered.

The Opening Gambit

Napoleon’s problem in Russia is an extreme case of the dilemma that faces any combatant at the beginning of a war: try to eliminate the enemy in one stroke, or take a more deliberate approach, securing advantages that can be built upon? The former offers the temptation of a quick and relatively low-cost victory; but if it fails, it risks sacrificing the best troops and equipment, leaving the attacker much worse off in the attritional phase that follows.

This choice was rarely so binary, especially in the modern era—high state capacity makes a loss in the opening battle far less catastrophe. The two logics are not even necessarily mutually antagonistic. After the initial German offensive in France ground to a halt in 1914, they were left occupying lots of high ground that put them in an excellent position for the war of attrition that followed.

The interplay between the two can nevertheless be difficult to fully appreciate. The Germans failed to properly exploit their position of 1914 by going on the defensive in the west, continuing to believe that a decisive victory must be won in that theater—even the Verdun offensive, expressly intended to bleed France out, followed the logic of decision. This delayed their ultimate victory in the east, leaving them unable to concentrate their full forces on the Western Front until after the United States entered the war.

Complex Tradeoffs

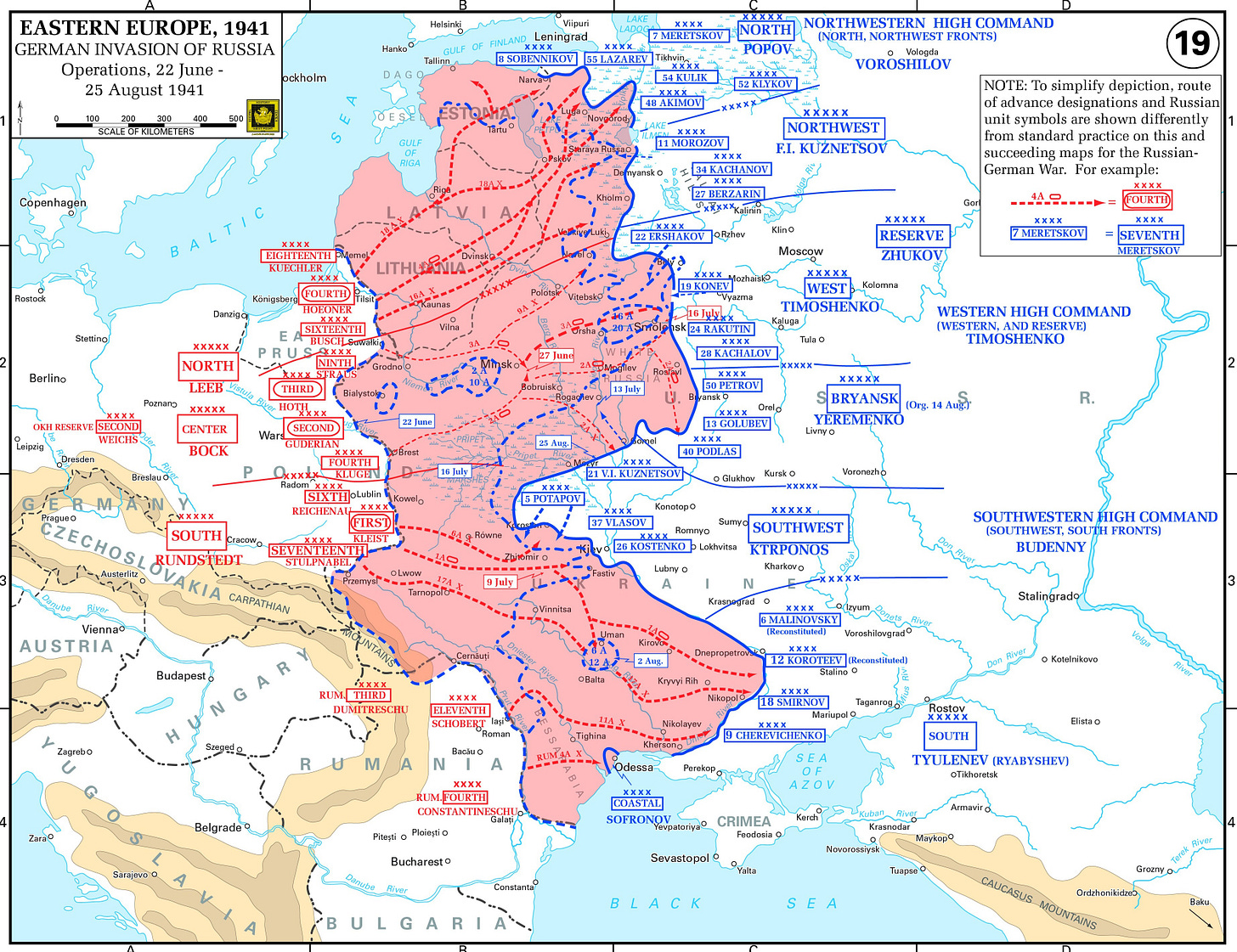

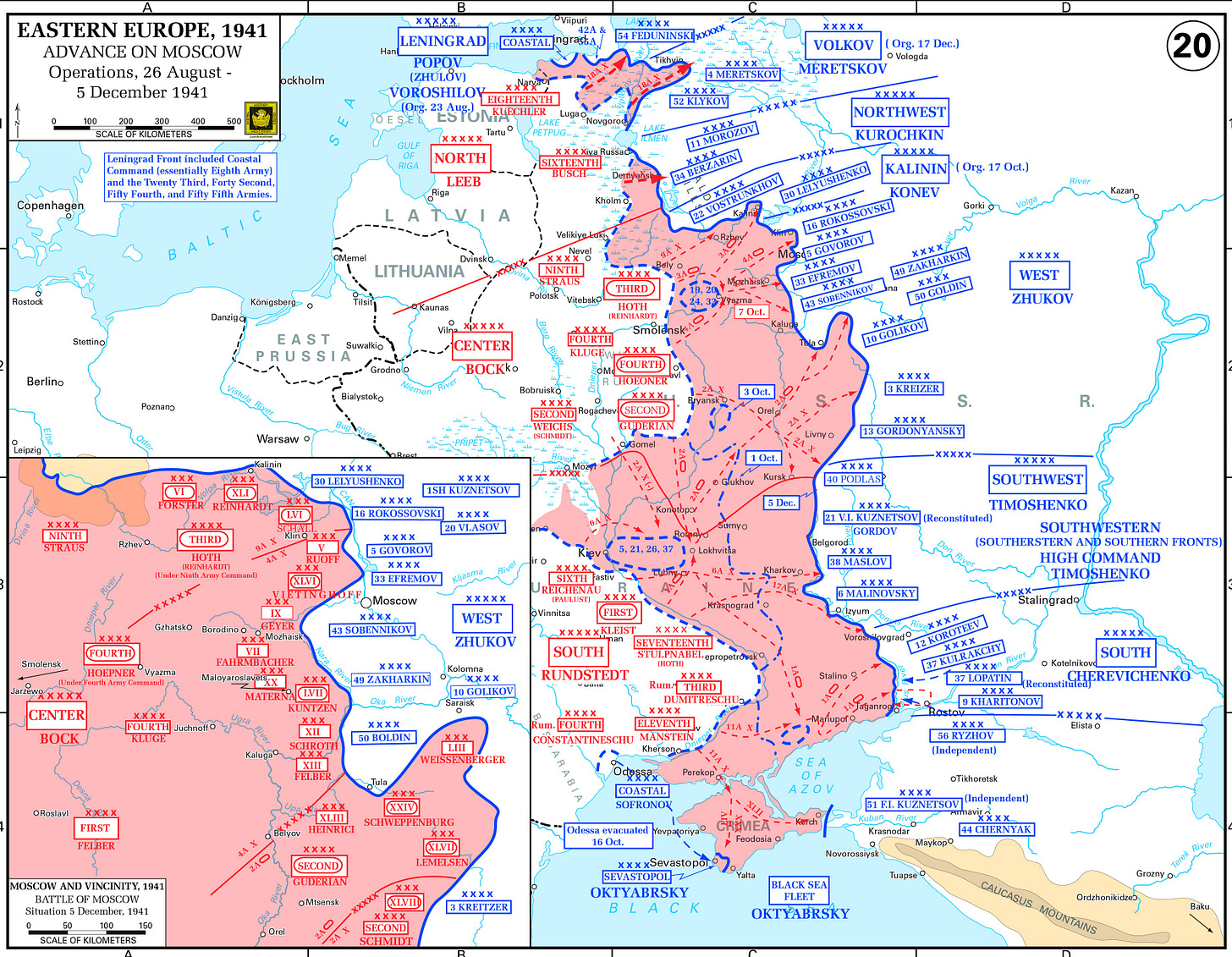

The shifting logic between the economic and the decisive can create complex tradeoffs that depend on varying time horizons and outcomes. Operation Barbarossa is a good example of this; and as with Napoleon’s invasion, Smolensk proved a key decision point during an invasion of Russia.

The Battle of Smolensk, which concluded in September 1941, revealed that Soviets reserves were much deeper than German intelligence had originally believed. Moreover, the heavy combat whittled away German front-line strength over the course of that battle, taking an especial toll on the mechanized infantry necessary for fast-moving breakthroughs.

Hitler therefore faced a choice between securing economically-valuable lands in Ukraine and the Caucasus which might shift the balance in a long-term war of attrition, and continuing to press for a quick victory with a drive on Moscow that year (he insisted that Moscow was no more than a geographical point, but his actions suggest he believed otherwise—justified by the city’s role as a political and transportation hub whose loss would seriously disrupt the Soviet war effort). In the end, Hitler attempted to split the difference: he sent a Panzer group to help encircle the Soviet armies around Kiev, securing one of the richest breadbaskets in Europe, then continued the push on Moscow in October.

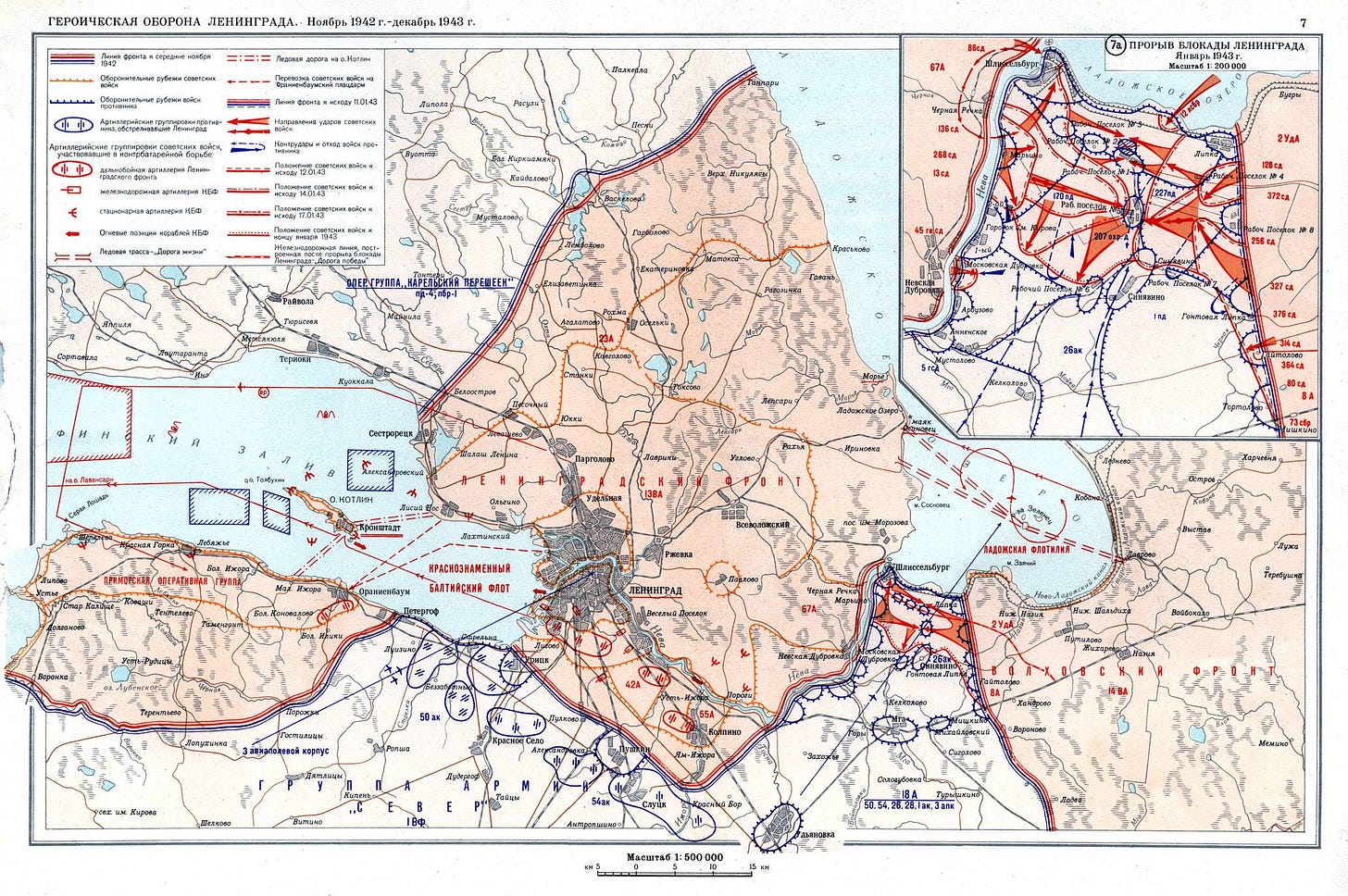

However, a third option was also available: the reduction of Leningrad. This was not as straightforwardly appealing, as it represented a complex blend of economic and decisive rationales. The biggest bottleneck on German efforts in the first years of the war was not manpower or war production, but available combat power. The rapid advance outstripped supply lines, making it difficult for replacements to reach the front—it was a logistics problem, not a resource problem.

The capture of Leningrad promised to ease that bottleneck. It was the last remaining Soviet naval base in the Baltic, and its reduction would open up shipping routes across that sea while giving the Germans a supply base for Army Group North. That in turn would open up a new axis of advance on Moscow, or at least the northern groupings of Soviet armies. However, capturing the city would itself cost blood and time, as would administering its civilian population and opening the port to supply shipments. That investment would not pay off until the following year, and moreover lay at the opposite end of the front from the economic objectives in the south.

In sum, an attack on Leningrad would require an immediate concentration of forces to take the city, which, even if successful, would represent a cost in the balance of forces in the near term. That might pay off in the medium term by allowing a decisive concentration, but if it failed, Soviet war production would inexorably tilt the balance in the long term. The interplay of conflicting logics across time horizons makes it impossible to gauge whether it would have been worth it (as it happened, Hitler’s decision to blockade the city and starve it into submission tied down considerable German manpower for over two years).

In the Event of Failure

It is very difficult for a leader to fluidly shift between these two logics, especially when that requires cutting losses and pivoting to an entirely new course of action amidst thick fog of war. Much of what characterized the greats such as Napoleon or Frederick was precisely their ability to manage this emotional rollercoaster most of the time.

There is no reliable way to discern the prevailing logic of a situation—and even when the tide is shifting, one is always tempted to hold out hope that a gambit will pay off. This underscores the importance of careful preparation: developing a thorough estimate of the situation; evaluating the tradeoffs among different eventualities and judging how to balance them; carefully setting phase lines, decision points, and branch plans; constantly updating the initial estimate and reevaluating assumptions; and being willing to fully act on one’s judgment.

As always, there is no substitute for knowing lots and thinking hard.

Thank you for reading The Bazaar of War, please like and share to help others find it. A lot of time and research goes into creating these pieces — you can help support with a paid subscription. This gives you access to monthly long-form exclusives which examine the deeper dynamics behind selected historical episodes (preview them here). You also receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.

Extremely interesting article by the way!

Sorry what’s “the HE race of the infantryman”?