Entrenched Tactics and Comparative Advantage: An Economic View of Warfare

David Ricardo’s principle of comparative advantage is one of those ideas from economics that crosses over to many other domains. It was first formulated to describe the relationship between trade and production, explaining why even countries that are relatively inefficient at manufacturing can retain an industrial sector. To use Ricardo’s original example, suppose that England is more efficient than Portugal at producing both cloth and wine. Intuition would suggest that free trade between the two countries would eviscerate Portuguese industry as cheaper English goods flood the market.

The theory of comparative advantage says otherwise. Labor and capital are limited resources. They are also largely immobile, whereas finished goods are highly mobile. Producers must therefore compete for market share with international rivals in the same sector, and also with domestic producers in other sectors for labor and capital.

An example. If English clothmakers are more efficient than both Portuguese clothmakers and English winemakers—that is to say, if they have both an absolute and a comparative advantage—then English entrepreneurs will naturally favor clothmaking over wine. Would-be Thames valley vintners will get a greater profit by converting their riverfront property into textile mills.

What is more interesting is how Portuguese winemakers also benefit from this. Even if they are less efficient than their competitors in England, so long as they are more efficient than Portuguese clothmakers—meaning they have a comparative advantage, but not an absolute advantage—then they can make the best use of Portuguese labor and capital. Portugal can therefore export wine to England in exchange for cloth. English vineyards, which have to compete with the domestic textile industry for labor, are undercut by Portuguese producers and driven out of business.

These dynamics help explain industrial patterns in the later 20th century, as developed economies continued to dominate more sophisticated manufacturing while textile manufacturing moved to poorer countries. Measured just in terms of man-hours, the first world remained far more efficient at producing both, but fierce domestic competition drove up labor costs to the point that it became unprofitable to manufacture low-end goods at home.

The Marketplace of War

There are many analogues between economists’ idealized models of perfect competition and the ruthless competition of flesh-and-blood warfare. This is most apparent in asymmetric warfare. Terrorism and insurgencies work by exploiting their comparative advantage in low-level attacks and intelligence gathering. Although first-world militaries are far better at these tasks—this much is evident from greatly skewed body count ratios alone—they are far better off investing in technology and advanced training. For the insurgents’ part, even supposing they could acquire more advanced equipment, it would be far too expensive to acquire them in sufficient numbers to be tactically effective (hence the Afghan phenomenon of warlords collecting “prestige weapons” that were rarely risked in combat).

This logic also applies to peer warfare, and neatly explains Soviet maritime strategy. Throughout the Cold War, the US had an absolute advantage in quality of both surface and subsurface vessels. But whereas any surface fleet would have been swept from the ocean relatively quickly, submarines had the potential to be far more effective. The Soviets consequently exploited this comparative advantage in submarines and built many more than the US, which exploited its own advantage in airpower to build more carriers.

War is not merely an optimization problem, of course. Even when distinct advantages tilt the balance in a certain direction, the synergies of jointness and combined arms require a broad range of assets; and even when those synergies are absent, there still remain certain tasks that can only be performed by a certain asset type—militaries must be far more “diversified” than a simplistic model would suggest (as are, in fact, real-world economies). Hence, America pioneered nuclear submarines, while the Soviets eventually built a substantial surface fleet.

The Optimization Trap

But what if things circumstances change all of a sudden, leaving a country with an entire industrial defense base unsuited for new conditions? This is behind the dynamics described at the end of last piece: when one arm or service proves to be especially effective, militaries come to depend on it too much. American airpower is a conspicuous example. This capability, developed in response to late Soviet armored superiority, and which proved its worth over Iraq in 1991, would be a positive liability in a future war if the United States were unable to gain air superiority.

(Reliance on airpower is also cited as a reason for America’s failures in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Vietnam, but that is mere blame-shifting. Whatever the weaknesses of US counterinsurgency, none of these conflicts were in any sense a military defeat: in all three, American leaders failed to appreciate the political question, either inadequately addressing it or setting completely unrealistic goals.)

Ukraine is an apt illustration, where capable IADS have prevented either side from gaining air superiority. If American forces were in similar straits fighting China, they would be hard-pressed to compensate via other means. Most discussion therefore focuses on the need to rebuild the defense base to a level that can produce at scale. But it is also worth looking at how these dynamics can play out when resources remain constrained.

Entrenched Tactics

Overdependence on a single arm was a problem as far back as the Middle Ages, when most Western European armies were built around a core of heavy cavalry. There were many reasons for this: social structure favoring a semi-professional warrior class, the relative difficulty of training effective infantry, the tactical advantage that European metalworking conferred to armored knights, the particular geography of Western Europe, etc. So powerful was the charge of European heavy cavalry that many armies were organized entirely around it; tactics and even campaigns were designed to optimize the chances of using it.

This caused problems during the Crusades, when those same armies encountered a very different sort of opponent. The Turkish armies they fought were also highly specialized, built around lightly-armored horse archers. These proved deadly for the more cumbersome Western armies, which had trouble coming to close quarters with the mobile Turks, especially on the open plains of Syria and Mesopotamia. Clouds of mounted archers could swirl around Crusader marching columns, dispersing in the face of a charge and reforming to counterattack until the Christians were completely worn down. Against this, what could the Crusaders do?

The natural solution would have been for Crusaders to adapt light cavalry tactics of their own. And indeed, they hired many local horsemen as auxiliaries, but these could only help on the margins, not produce the highly-competent and motivated cavalry that Crusading warfare required.

Unlike modern militaries, medieval armies had no centralized training. Feudal levies were raised from the semi-professional warrior class, which was taught how to fight by their local lords. Knightly combat, characterized by heavy mounts, armor, and massed lance charges, was moreover a class signifier, which the feudal aristocracy which commanded armies was loath to abandon. Force structure was therefore a product of the wider culture, not a result of accumulated bureaucratic decisions, yet the effect was the same.

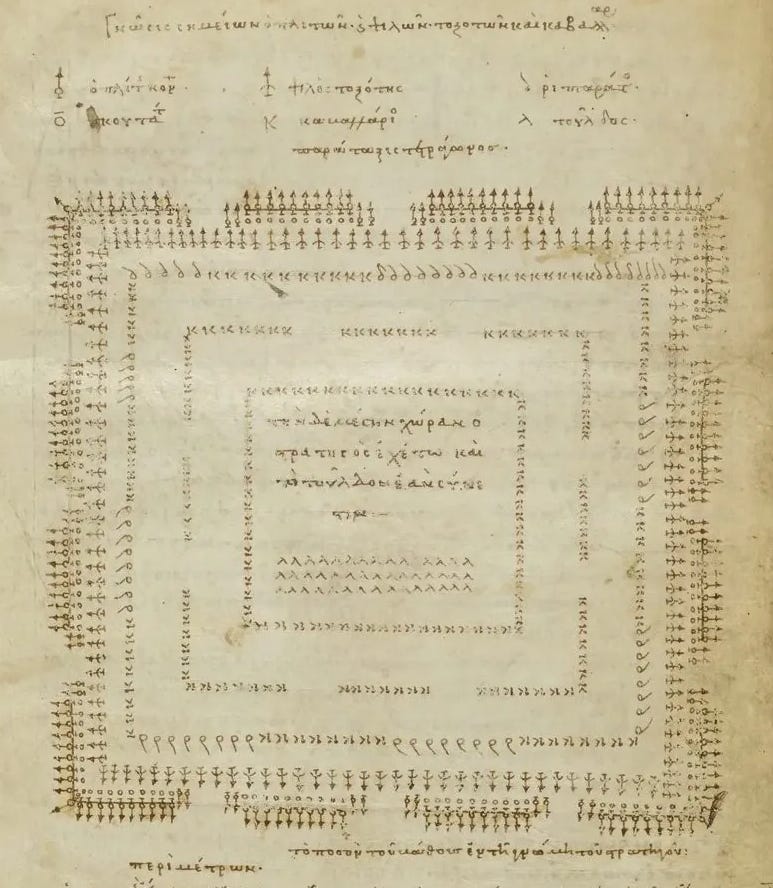

This meant that adaptation had to come at other levels of war—mostly the higher tactical and operational. Crusader armies adopted highly-disciplined march formations: hollow rectangles of infantry which sheltered the cavalry from enemy arrows. Spearmen in the outside line formed a solid wall, while archers and crossbowmen shot back at enemy cavalry. If the pressure got too intense, the knights would charge out through friendly lines and drive the enemy back. (This likely did require additional training, especially for Crusader infantry, which appears to have been better trained than their cousins back in Europe).

This could only frustrate Turkish tactics, not deliver victories. But it allowed them to safely execute limited marches between castles or fortified camps, giving them flexibility to develop things at the operational level for an attack.1 Even then, it remained difficult to take the offensive at either the tactical or operational level—all the more so since they lacked the resources to endure a heavy loss. Their strategy accordingly became increasingly defensive: they relied on their own cohesion, reinforced by the existential threat they faced, to outlast the unity of the Muslim world, which faced strong centrifugal forces. As it happened, this did not work: Saladin was able to keep his empire united long enough to annihilate the Crusader army at Hattin and contain the ensuing counteroffensive of the Third Crusade.

This pattern is evident everywhere in all time periods: deadlock in one area shifts competition to other levels and domains. The higher and wider this goes, the more costly it ultimately proves. The Crusades as a whole were an enormous mobilization of resources: two centuries during which countries from all over Western Europe and the Islamic world poured resources and manpower into a narrow strip along the Mediterranean’s eastern shore. Even larger were the Arab-Byzantine wars, fought for three centuries without any major strategic victories, until Arab strength fractured under the growing weight of Byzantine power. Modern warfare compensates for shorter duration with much greater intensity: World War I is the archetype of a tactical and operational stalemate causing both sides to deliberately try to bleed the other out.

Shifting the Playing Field

The combination of rapid technological change with heavily-entrenched tactical systems makes modern warfare more uncertain than ever before. It is impossible to tell whether an existing comparative advantage will simply disappear: 2022 showed that masses of armor could no longer simply punch through a capable defense. Although Russia has had enough of a resource advantage to keep the war going, it has been unable to restructure its forces mid-war to effect a breakthrough—pushing the conflict into the realm of strategic attrition.

In general, the more entrenched a country’s tactics are—whether because of legacy equipment, limited industrial capacity, or cultural reasons—the harder it is to adapt. The natural response, then, is to look straight to those other levels and domains from the outset.

When it comes to China and Taiwan, this is why many American defense analysts recommend not trying to actively contest an invasion: better to simply give Taiwan the weapons it needs to hold out (porcupine strategy) and impose a distant blockade on China, hoping to choke off its energy and food supply before an invasion can succeed. Likewise, many raise the possibility that China could blockade Taiwan until it capitulates, rather than risk a difficult and costly amphibious assault.

This does not preclude advancements at the tactical level—China continues to develop its amphibious capabilities while America looks to counter them. But the greater the complexity of a tactical system, the more inflexible it is once the missiles begin to fly. That makes it a practical necessity for planners to expand their operational and strategic capabilities well beyond the bounds of an envisaged conflict.

Thank you for reading The Bazaar of War, please like and share to help others find it. A lot of time and research goes into creating these pieces — you can help support with a paid subscription.

This gives you access to monthly long-form exclusives which examine the deeper dynamics behind selected historical episodes (preview them here). You also receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.

Interestingly, this blunting of Muslim cavalry’s tactical advantage—reducing its comparative advantage, so to speak—induced a change in their armies’ composition. They seem to have acquired more heavy cavalry that could break through the enemy’s weakened lines, rather than waiting indefinitely to wear them out. This was more a matter of acquiring better armor than changing their fighting techniques, which were just as constrained as the Crusaders—they never mastered the massed charge that made Western knights so formidable.

An interesting piece!

That said, light cavalry was negated by firepower. Richard III relied on a huge force of mercenary crossbowmen in the Third Crusade. The crossbow was also a critical element in the defeat of the Mongol invasion of Hungary (along with more heavy cavalry and local fortifications).

Likewise, in the 16th and 17th centuries, Russia embraced gunpowder weapons to the same end against the light horsemen of the steppe, notably the Tartars.

See The documentary called Birth Gap on YouTube. None of this will matter soon. Well written though. Thank you