Lines and Reserves, Part 3: Linear Tactics

This is the third of a multi-part series. You can read the second installment here.

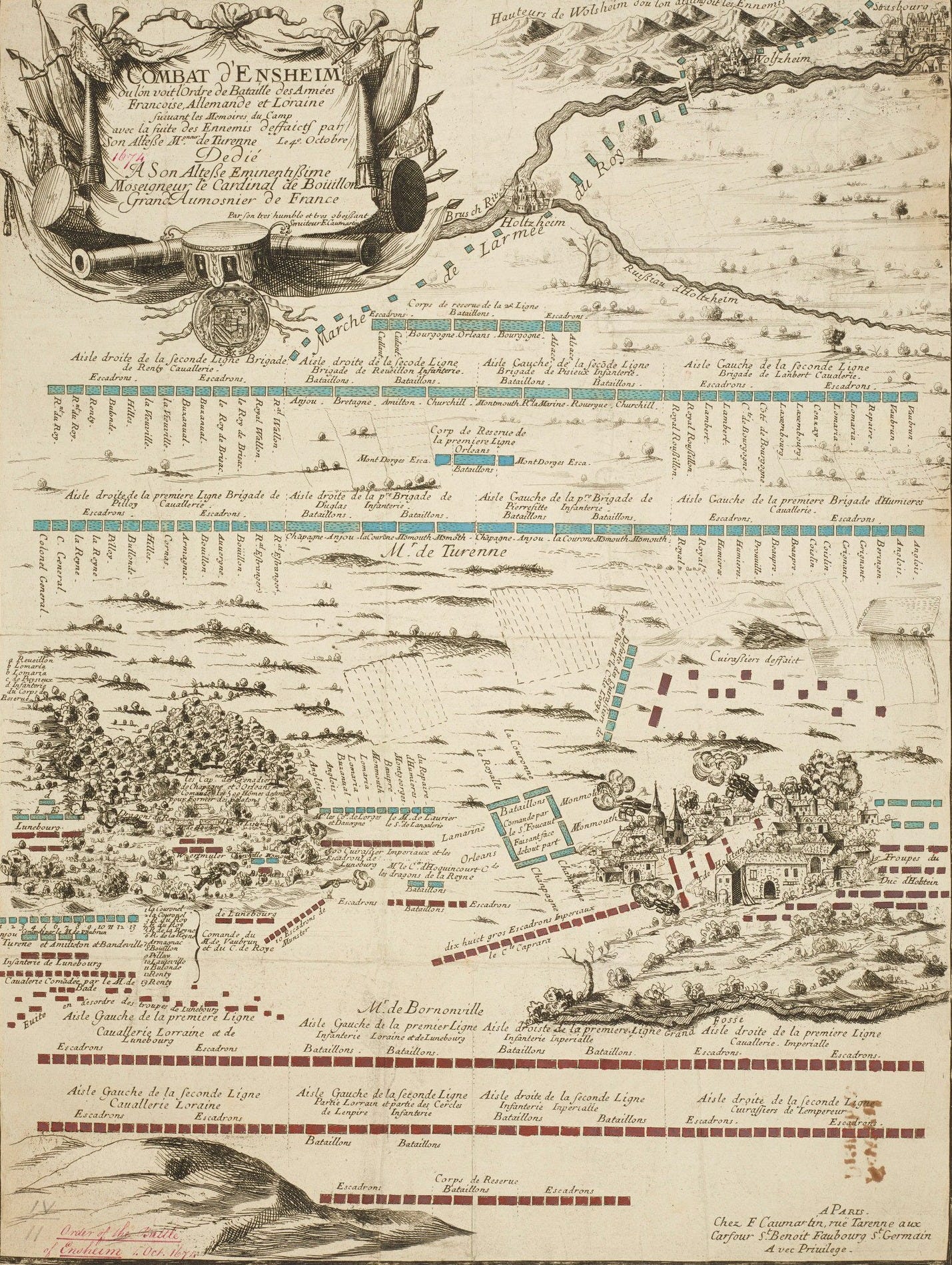

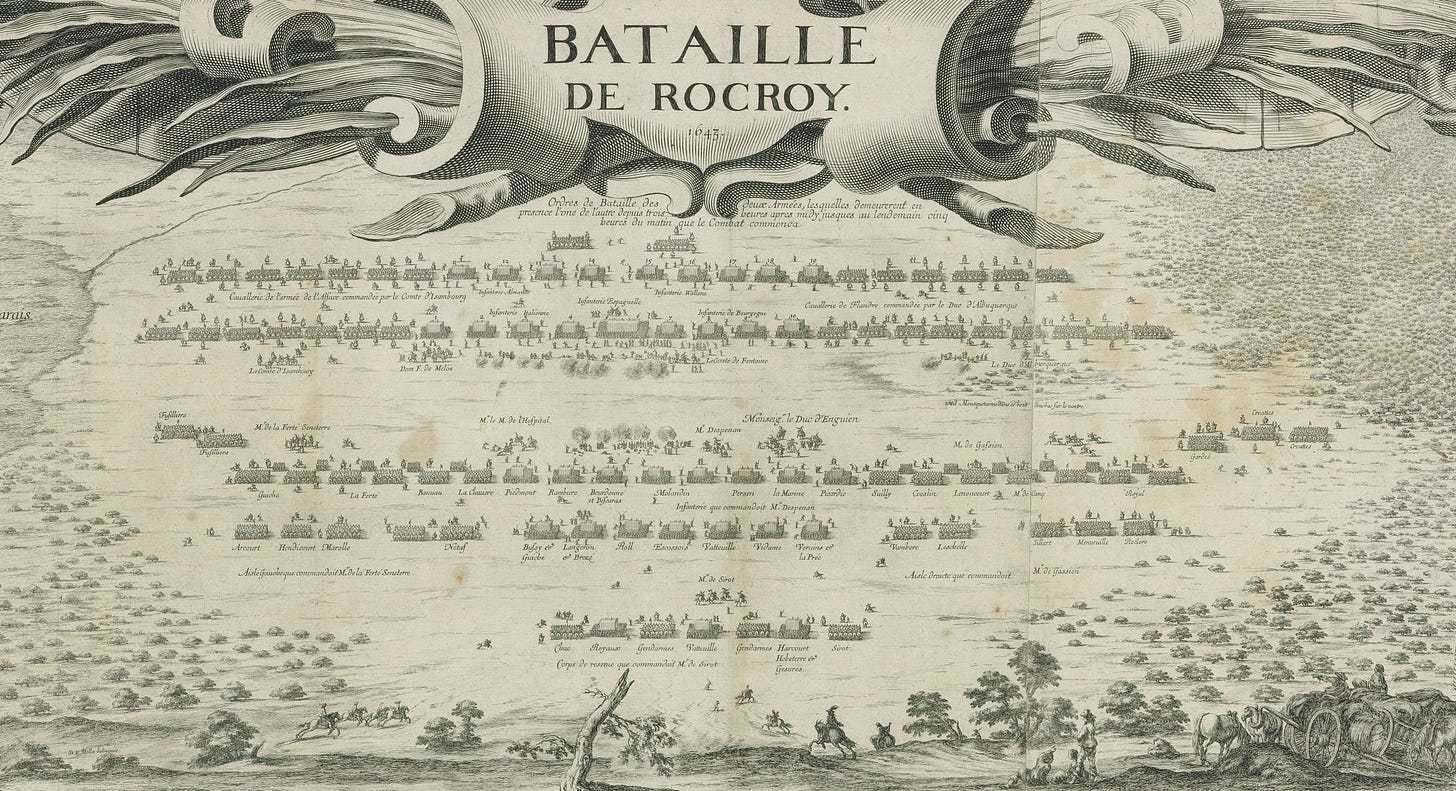

The last part in this series concluded with the Battle of Rocroi, in which we see developments of the previous half-century come to full form. As the ratio of pikemen to musketeers gradually inverted, the checkerboard deployment of mutually-supporting blocks gave way to longer, thinner formations that maximized firepower to the front. To make up for the loss of the pikemen’s staying power, these were deployed in multiple lines, allowing forward lines to fall back behind the safety of the rear, or rear lines to push forward and sustain the attack.

A standard formation was two lines, with infantry in the center and cavalry on the wings, backed by a smaller reserve. This combined the concept of a general reserve, tasked at the commander’s discretion, with secondary lines, which had standing orders to support the foremost line. For armies up to forty or fifty thousand strong, this balanced the need for all-around resilience with the flexibility to strike decisively at a single point. As we already saw at Rocroi, the double lines gave the reserve time to stave off a Spanish breakthrough on one flank then participate in an enveloping attack.

Strikingly, the reserve was a mixed force. This was a departure from ancient and medieval armies, which used a small all-cavalry force as the reserve (typically the commander’s bodyguard, e.g. Alexander’s hetairioi). This quickly became a standard deployment in Western Europe for battles on open terrain. Armies marched in “order of battle” so they could rapidly form up, even if they immediately adopted different dispositions for combat.

This basic template gave armies tremendous staying power: even when they faced defeat, the reserve could usually hold off the enemy long enough to cover an orderly withdrawal.

This was especially true when faced with unconventional tactics. In 1690, 30,000 French troops under Marshal Luxembourg attacked a similarly-sized Allied army occupying a strong position at Fleurus in the Spanish Netherlands. Luxembourg marched to the battlefield in two columns: the first deployed in two lines and launched a fixing attack on the center, while the second marched around the enemy left and formed up for an attack upon the flank.

Waldeck, the Allied commander, rushed troops from his reserve and the unengaged part of his left to form new lines on this flank. Although the Allies suffered heavy casualties before being forced to withdraw, Waldeck’s judicious use of the reserve averted total annihilation.

The Wars of Louis XIV

Longer and thinner lines coincided with another trend: a sharp rise in army sizes. When Louis XIV assumed direct rule of France in 1661, he made it his primary ambition to secure France’s position as the foremost country in Europe. With able ministers such as Colbert and Louvois, he reformed the finances and army, allowing him to mobilize vast resources for his wars of expansion. Louis played the tune to which the rest of Europe danced, and rival powers were forced to scramble just to keep up. Field armies exploded in size all around Europe, creating new difficulties for command-and-control—Turenne noted the difficulties of leading an army more than 50,000 strong.

Several self-reinforcing factors transformed the usual arrangement. With a wider frontage, reserves had to travel farther. At Rocroi, the French reserve line was about a third the length of the army’s width and contained about a sixth its total strength. Simplistically, this meant that it had to travel no more than 800 meters to get into position behind either wing and twice that for a flanking attack. In an army larger than 50,000, those numbers would be more than doubled, risking disaster in the event of an enemy attack on the flanks.

The sheer size of armies made deployment a complex and lengthy process, and it was no longer possible for two armies to converge on a piece of open ground and form up in the face of each other. Instead, one army typically occupied a strong piece of ground and effectively challenged the other to battle. The challenge for the opposing general was to attack uphill across a wide front against an enemy that was likely dug in. The simplest solution was to concentrate his attack: to puncture the line at one or a few points then roll up it by the flanks.

This was usually done via an attack in column. A column consisted of multiple short lines which assaulted in successive waves—rather like the French attack at Poitiers—while rest of the army fixed the enemy line. This not only eased the problem of controlling his own wide front, but took advantage of the enemy’s dispersion.

Generals on the other side responded in several ways. It was common for such wide battlefields to encompass several villages, which would be used as improvised fortifications, anchoring the line at several points. Less protected sectors, which the enemy was likely to use as avenues of approach, might be covered by three or more lines, while it was not uncommon for certain sectors to hold forces farther to the rear. If one point came under particular strain, battalions and squadrons could also be pulled from rear echelons in quieter sectors to deal with the crisis. The upshot was that the general reserve was typically committed to certain tasks before the battle even began, with only a small force retained for general contingencies.

These dynamics were already on display in 1692, when an 80,000-strong Allied army under William III attacked an equal French force under Marshal Luxembourg near the village of Steenkerque. Rather than engage the entire line, he marched his army to the battlefield in three separate columns which were to converge on the French right. In the event, the attack was poorly coordinated, and only a single column was in position to attack following the initial cannonade. Although it broke through three lines of French infantry, Luxembourg was able to transfer cavalry to contain the penetration and ultimately drove them off with heavy losses.

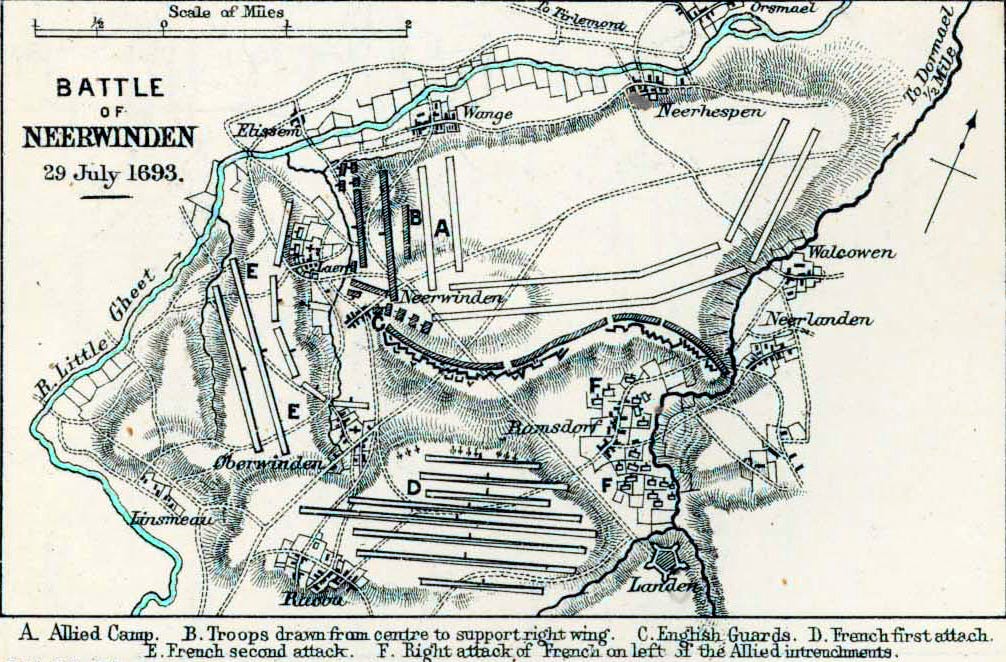

The following year, it was Luxembourg’s turn to attack William. 50,000 Allies were entrenched in a 6-km crescent on a height around the village of Neerwinden. Luxembourg, who had 75,000 men, concentrated his attacks on the Allies’ center and right, allowing William to contract his lines and redeploy in depth: a single line of infantry manned the fortifications, backed by two lines of cavalry to contain any breakthroughs. Luxembourg sent two deep columns against the enemy right in succession, but these were repulsed as William rushed reinforcements from the rest of the line; a third, much weaker column then broke through the depleted center, forcing the Allied army to flee the field with heavy casualties.

Linear tactics truly came into their own at Blenheim in 1704. The 56,000-strong Franco-Bavarian formed up on a 6-km front, with the Danube protecting their right, wooded hills on their left, and a streambed running across their front. Their position was also anchored by three villages, the rightmost of which was Blindheim (whence “Blenheim” in English). By using these as makeshift fortifications manned by infantry, they could use their cavalry to cover the gaps in between. The remainder of the infantry formed a third line behind the cavalry in certain sectors or was deployed behind the villages as a local reserve.

Against them, the Allies formed up in two corps, with Marlborough commanding on the left and Eugene of Savoy on the right. Eugene was to fix the French and Bavarian left while Marlborough launched the decisive attack against the right. His main effort was a column six lines deep tasked with capturing Blindheim, which would expose the French flank support an attack against the center.

Two critical decisions swung the course of the battle. The first involved the repositioning of troops. Marshal Tallard, on the Franco-Bavarian left, saw an opportunity to send his cavalry against Marlborough’s right flank, which would split the Allied army in two. Marlborough desperately called for help to Eugene, who sent several squadrons from his second line to head off the attack.

The second decision came around Blindheim itself. The French commander there, anxious in the face of the attacking column, threw the entire local reserve into the village. Not only were these battalions ineffectual in its cramped confines, but this left nothing to spare when a concentrated Allied assault broke through the adjacent French cavalry line. Blindheim was left completely surrounded, trapping a large proportion of the French infantry, and the rest of the army was forced to flee. The Franco-Bavarian left managed to escape in mostly good order, but the right was completely annihilated. Nearly a quarter of the army was killed or wounded and another quarter captured, the majority of which were soldiers trapped in Blindheim.

The Battle of Blenheim illustrates the full complexity of 18th-century tactics: fortified points, local reserves, attacking columns, and lines deployed three or more deep. The battle hinged on decisions about how and where to employ rear-echelon troops, more than on initial dispositions. Marlborough displayed similar skill two years later at Ramillies: as an initial attack against the Franco-Bavarian left drew reinforcements from the rest of the line, he transferred second-line troops to his own left. He then formed his left into four lines and broke through the three lines of cavalry on the French right.

Mid-18th-century Battles

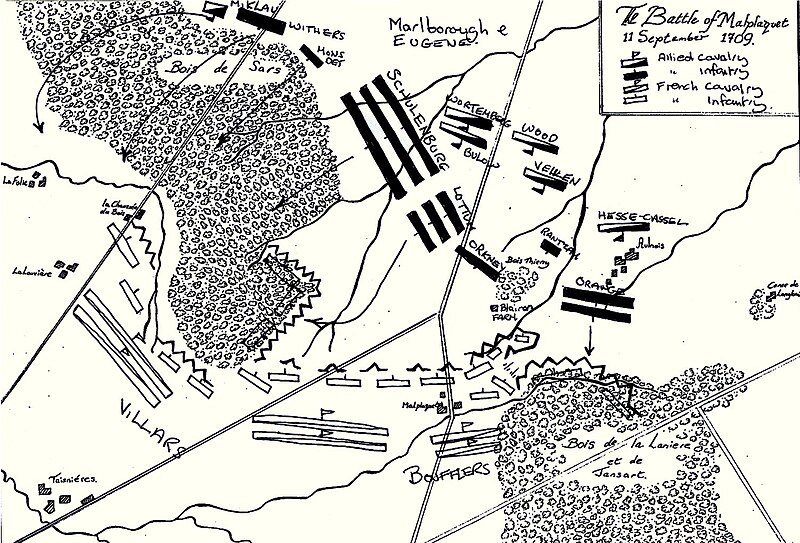

Because of the inherent risk of breakthrough on an extended line, 18th-century generals often preferred to draw up on a narrower front in three or more lines. Villars did so at Malplaquet in 1709, when a desperate situation along France’s northern border forced him to fight a battle against unfavorable odds. He did so by digging in between two woods not far from the Allied army, effectively inviting them to attack. He placed his infantry in a single line behind earthworks in the woods and the 1.5-km gap between them, and posted his cavalry in two lines behind them.

The Allies eventually forced their way through the woods on the French left, drawing off the cavalry posted behind the center; this in turn allowed a massive Allied column to break through the center. The French cavalry ultimately plugged the breach, but their position had been fatally compromised. This was not a straightforward defeat, however: over the course of the fighting the French had inflicted twice the casualties they had sustained, and they jubilantly withdrew from the field in perfect order.

Another French general employed similar tactics more successfully at Fontenoy, where in 1745 drew up 56,000 men in a 4-km arc between a wood and a river. The infantry was drawn up in a single line, with small reserves on the flanks and center, and backed by two lines of cavalry. The village of Fontenoy, at the vertex of their salient, and Antoing on their right served as hardened positions, and several redoubts were constructed along the line. The French cavalry and infantry reserves were able to contain and repel a British column on the left, while defenders in the two villages and redoubts drove back Dutch and Austrian assaults.

The peril of too long a line was dramatically illustrated at Leuthen, where in 1759 the Austrians drew up their 65,000 men along an 8-km front. This was only somewhat less dense than French dispositions at Blenheim, but their open flanks forced them to keep most of their cavalry on the wings, with just a modest reserve to spare. The Prussian commander, Frederick the Great, exploited this by demonstrating at one end of the line to draw their reserves, then rushing the rest of his army to the other end to plow through their left flank in a concentrated attack.

Towards the End of the Century

Generals continued to innovate and improvise throughout the 18th century, as well-drilled troops gave them the flexibility to adopt a wide variety of dispositions. Large armies generally deployed in two long lines backed by local reserves or third lines at key spots, although the older two-line-plus-reserve endured in smaller battles—at tiny Culloden, the British held a fifth of their 7,000 men behind the second line.

Armies went through another period of explosive growth in the 1790s as the Revolutionary France instituted the levée en masse. These gargantuan hosts added new complications to deployments and the ways generals responded to contingencies. We will look at this period through the 19th century in Part 4.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Please like and share if you enjoyed, it helps more people find this. You can also support with a paid subscription, supporters receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529 and get access to exclusive pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.

Fascinating detail!

By the way, did you intend to name the French general at Fontenoy in 1745?

This is quite an interesting read.