Why Study the Wars of Louis XIV?

With each passing year, the practical lessons of World War II become less relevant. The great war that defined our understanding of mechanized warfare and airpower was fought with technology that is now almost a century old. Precision weapons, universal motorization, advanced airpower, and omnipresent surveillance have radically altered even the smallest tactical interactions. Yet it remains a source of fascination, and year after year generates insightful new research.

Scale is obviously part of it: no war before or since has seen so many men fighting over such a wide geographical area for such high stakes. But there is something else that makes it an inexhaustible object of study. There is something complex and compelling at every level, from the individual soldier up to the high commands. At the tactical level, new armor and aviation tactics were explored. At the operational level, it saw both fast-moving envelopments and slow-developing breakthroughs; deliberate island-hopping in the Pacific and carving lines of operation through the jungles of Burma.

At the strategic level, each theater affected the others in complex ways, posing tradeoffs and dilemmas. Moreover, there was lots of interaction between levels: different theaters demanded radically different tactics, different tactics enabled different operational schemes, and so forth.

Few wars merit such thorough examination. The Napoleonic Wars were interesting at the tactical and operational levels, but only rarely at the strategic. Napoleon was such a virtuoso that he could usually win with a single campaign, driving relentlessly for the enemy’s jugular. World War I, by contrast, was interesting at the tactical level, intermittently so at the strategic, but the nature of the fighting ruled out any moves of operational significance (on the Western Front, at least). Meanwhile, other conflicts such as Vietnam were by their nature wars of tactics, lacking any operational or strictly military strategic coherence.

Of all the wars that receive intensive scrutiny, only the American Civil War comes close. The war was decided by campaigns east and west of the Appalachians, complemented by actions at sea, on the Mississippi, and farther west. Each of these theaters saw complex operations which led to large-scale and interesting battles; unsurprisingly, the Civil War is second only to World War II in the US market for military history.

From the point of view of practical military history, these kinds of wars are extremely useful. Studying the most complex examples allows one to see the full range of military decision-making: how actions at one level affect options at another, the corresponding tradeoffs between them, the reasoning behind ostensibly foolish decisions and the folly of seemingly sensible ones, etc. Yet several wars fulfilling these criteria, fought in 17th and 18th-century Europe, are severely neglected in anglophone historiography.

Louis XIV was the most belligerent king in French history, beating out a very competitive slate. Between 1672 and 1714, he waged three major wars that embroiled much of Western Europe (and a couple smaller ones). A string of talented ministers allowed him to mobilize more of France’s resources than ever before, which he used to wage war at an unprecedented scale. These conflicts were fought in several different theaters and continents at once during a time of rapid tactical evolution, which brought a corresponding variety of operational dynamics.

The Wars

The first of these, the Franco-Dutch War, began in 1672 with a French punitive invasion of the Netherlands but rapidly expanded into a far-flung war that lasted until 1678. Both sides pulled allies into the conflict, and fighting broke out in the Rhineland, Italy, the Baltic, North America, the Caribbean, and the Atlantic. This represented a new era: in a relatively short time, two rival coalitions formed and went to war. The last time anything like that happened was during the later Italian wars over a century earlier. This time the geographical extent was much greater, setting a precedent for the rest of the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Nine Years’ War (1688-97) was very different. France alone fought a large coalition to a draw, maintaining an army of nearly 400,000 men—more than any other time until the Revolution a century later. Combat took place in the same theaters as the previous war and extended to Spain, India, and Ireland. Ultimately, the war ended with the restoration of the settlement that ended the Dutch war, leaving all parties dissatisfied.

Western Europe saw just four years of peace before the War of the Spanish Succession broke out in 1701. The Spanish king Charles II named Louis’ great-grandson his heir, raising fears that the crowns of France and Spain would be united in one person, giving the Bourbons an unassailable hegemony in Europe. This time the French fought alongside Spanish forces, who waged what was essentially a civil war for control of their country, and several smaller allies that Louis struggled to keep on his side. This was the longest war by far: the final peace treaty was not signed until 1714, a year before Louis’ death. Although it ended with a Bourbon on the throne of Spain, that country had to cede many of its territories and the war was ruinously expensive for all involved.

All told, these wars saw a combined 29 years of campaigning. The diplomacy and grand strategy was extraordinarily complex, as all the players had to balance their local interests against the growing threat of French preponderance. The financing and economics of the war are also fascinating, vastly exceeding any before. Finally, the wars brought the French naval rivalry with Britain into sharper focus, persuading Versailles to focus more on commerce raiding and protecting overseas colonies in the 18th century.

The Armies on Campaign

Wars of this scope and scale naturally saw many engagements. The linear tactics that had emerged in the mid-17th century were coming into maturity, aided by the transition from matchlock to flintlock muskets. As infantry firepower grew, their ranks thinned and their fronts expanded, creating new challenges for generals who had to manage much larger battlefields than ever before.

Siege warfare was also advancing apace. The star forts which first appeared with the advent of gunpowder artillery reached dazzling levels of intricacy. Sébastien le Prestre de Vauban, Louis’ chief engineer, designed many of these specimens, and also developed a system of multiple parallel trenches for besieging them.

These tactics did not lead to operational uniformity across theaters, however. The sheer number of fortresses and water obstacles in the Low Countries forced a slow, deliberate World War I-style advance through one line of fortifications after another. Campaigns in Germany and Spain were much more fluid and mobile, allowing for more open-field battles. Italy was somewhere between the two: it saw several dramatic large-scale maneuvers, but a series of north-south running rivers anchored by strong fortresses created natural defensive lines. This is not to mention the fighting in the Americas or India, where much smaller European armies fought alongside native allies.

Coalitionary Wars and Theater Strategy

These wars were not the only major European conflicts of the period which reward similar study. The Great Turkish War raged between the Habsburgs and Ottomans during the last two decades of the 17th century, while the Great Northern War was fought around the Baltic during the first two decades of the 18th.

Louis’ great-grandson and successor Louis XV also fought three major wars, which followed a remarkably similar arc to those of his great-grandfather:

The War of the Polish Succession (1733-35) started out as a limited expedition over a point of royal honor, but quickly turned into a larger European war.

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48), like the Nine Years’ War, was the zenith of French arms, but these victories bore no strategic fruit and the peace largely confirmed the status quo.

The Seven Years’ War (1756-63) was the great disaster, a ruinously expensive war that saw several major battlefield defeats and the loss of most of France’s North American colonies.

Yet the dynamics of these wars were subtly different. The coalitions that fought these later wars were not so singular in their purpose: these were marriages of convenience, each member largely pursuing its own separate goals—victory for one ally did not guarantee a good outcome for the others. War aims were accordingly more a wish-list of territories than a common set of desired outcomes.

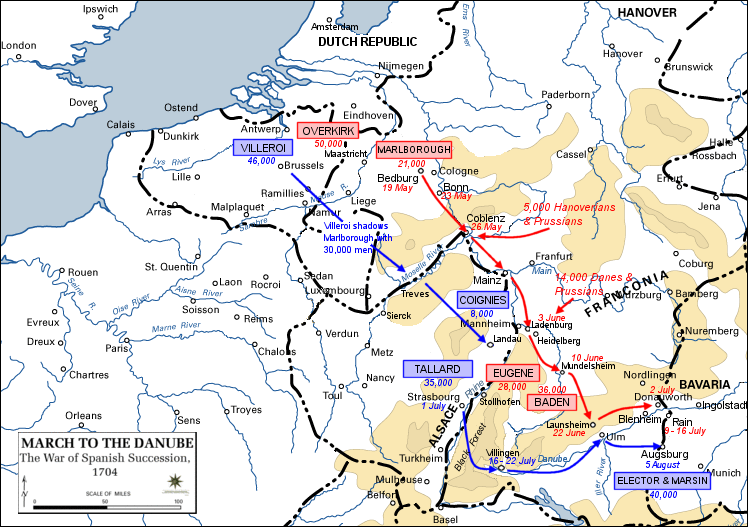

Not so for the wars of Louis XIV. The countries fighting Louis recognized that their individual objectives could only be accomplished for the most part through a coalition victory; France’s allies likewise depended on an overall French victory to achieve their own aims. This made military strategy much more interesting. Both sides faced a delicate balancing act, trying to preserve their position in one theater while making gains in another. This resulted in several dramatic shifts in the action as one side tried to surprise the other by reinforcing a quiet front at the beginning of the campaigning season. Marlborough’s famous march from the Low Countries to Blenheim was in reaction to one such move by the French. Toward the latter part of the War of the Spanish Succession, the allies faced the dilemma of continuing the struggle for Spain or trying to deliver a knock-out blow by marching on Paris.

The utility of military history lies in the way it gets us to think through problems. More complex wars, with a tighter connection between the tactical, operational, and strategic (not to mention the economic, diplomatic, and grand strategic) provide much more grist for the mill. As such, the wars of Louis XIV deserve similar attention from military and popular audiences as World War II and the American Civil War.

The next Dispatch will be on war strategy in the War of the Spanish Succession. I’ve published several other pieces on the period:

The northern theater in the War of the Spanish Succession, on how the relationship between tactics and operations created a very similar dynamic to the Western Front of World War I.

More on the same, framed as a discussion of the relationship between maneuver, position, and mobility

The last piece on lines and reserves takes us up to the cusp of this period; part 3 will cover the wars of Louis XIV through Napoleon.

For a good English-language overview of the wars, I recommend John Lynn’s The Wars of Louis XIV 1667-1714 (expensive, but many libraries carry it). He has also written a shorter book on the period with Osprey, The French Wars 1667–1714: The Sun King at War (I haven’t read it, but Lynn never disappoints). James Falkner wrote a decent overview of the War of the Spanish Succession, and has written much else on the period.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529 and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

A number of things were happening at various levels through these periods that affected the evolution of warfare. At the tactical level, matchlock muskets were slowly replaced with flintlocks (at first called firelocks) as first the escorts for wagon loads of gunpowder were given the new flintlocks so that the infantry didn't have to carry lit matches while near the gunpowder. Pikemen were eliminated as more flintlock armed soldiers filled the ranks and were given bayonets to put on the ends of their flintlocks to defend against cavalry. Soldiers carrying matchlocks had lined up in their formations with as much as three feet between individual soldiers so that they didn't get in each others way while executing the complicated loading and firing process. Flintlock armed soldiers could stand shoulder to shoulder and rear ranks could stand closer and place the barrels of their weapons between the heads of the soldiers in front of them. Tighter formations meant more bullets could be fired at the enemy and the use of iron ramrods meant the bullets could fit a little more tightly as they were forced down the barrel and then when fired the round flew out of the barrel at higher velocity which translated into greater range. The number of fortresses increased as each nation tried to create a network of defended supply depots to support their armies in the field rather than see the army slowed down by having to carry all of its supplies for an extended campaign along with it. Coalition building evolved from the use of a large number of essentially independent military contractors to provide troops for hire, to the creation of modern nation states and principalities which raised 'national' armies that could fight alongside the armies of allied nations. There were indeed many, many changes in how wars were fought across this period.

Supply chain, communications, advancing technologies and the need for alliances due to the economics of deploying the means of war.