Mobility and Maneuver: False Friends?

Over the course of Ukraine’s recent counteroffensive, there was much discussion over whether it would break out of positional warfare and restore a war of maneuver. Position, like attrition, is often held to be the opposite end of the spectrum from maneuver. As with the contrast between attrition and maneuver, this is a false distinction that only confuses things.

An older dichotomy was between position and movement. The two have been held as opposites since the eighteenth century at least, reflecting debates over whether to fund fortifications or field armies. Magazine-bound logistics made it difficult to move deep into well-fortified enemy territory, but building and maintaining fortresses was enormously expensive.

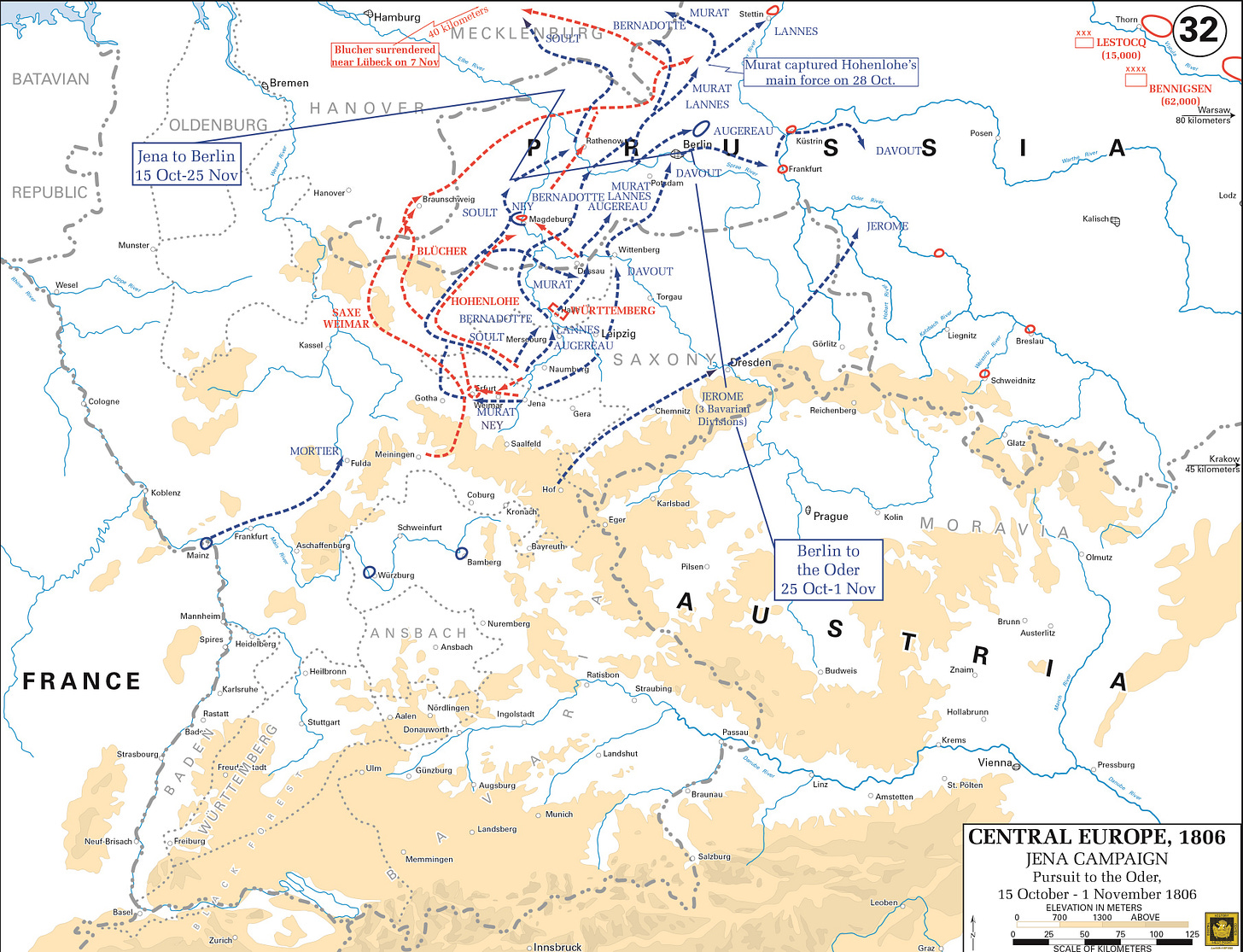

The victories of Napoleon and then Moltke in the nineteenth century seemed to settle the debate in favor of mobility. Fast and decisive actions allowed them to overwhelm their opponents with superior concentrations before they were ready.

It should be carefully noted that Napoleon and Moltke were for the most part not maneuverists. Both certainly made good use of maneuver when it suited them, especially operational envelopments, but this was secondary to overwhelming any enemy they encountered. This is apparent in Napoleon’s most inspired feat of maneuver, when he enveloped an entire Austrian army at Ulm and forced its surrender at no cost. Yet this elegant maneuver was only incidental to his larger purpose, which was to destroy that army before a larger Russian and Austrian force could link up with it; it hardly mattered how this was accomplished, so long as this was done swiftly. As if to illustrate the point, a year later Napoleon rapidly defeated a Prussian army before Russian reinforcements could arrive—this time through a pair of frontal battles at Jena-Auerstadt.

A Theory of Maneuver

It was under the influence of the maneuverist school in the 1970s and 80s that maneuver came to displace mobility as the opposite of position. William Lind, John Boyd, and others conceived of it as something more abstract than movement relative to the enemy; instead, it could be any series of rapid and disorienting actions that disrupted the enemy’s system. One element of this was time: they would argue that by attacking before the enemy was ready or had time to concentrate, Napoleon was in fact exercising a form of maneuver. Thus, while this view of the concept was not synonymous with mobility, it did encompass it, and the more general term gained broader currency.

The maneuverists made no such connection between attrition and position. If anything, the opposite: they argued that the infiltration tactics developed late in World War I were a prototypical example of the maneuver used in the next war. This point did not catch on as much in the popular imagination, however, most likely because WWI was not won through such techniques. Korea likewise fell into a bloody stalemate and Ukraine appears headed for the same, linking their positional and attritional aspects.

The result has been that mobility and maneuver are used interchangeably for one end of a spectrum, position and attrition for the opposite. We have already seen how maneuver and attrition are a false dichotomy; throwing mobility and position into the mix have only worsened the terminological jumble. To untangle it, it is worth a brief look at how the concept of maneuver entered military thought in the first place.

The March-Maneuver

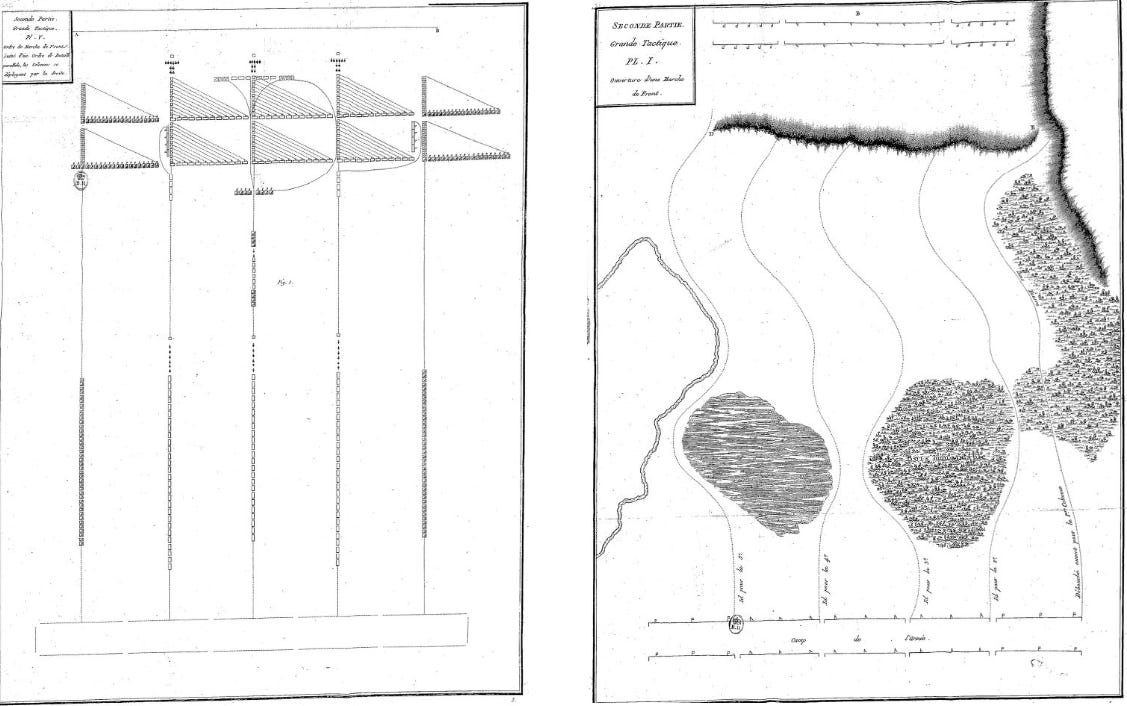

“Maneuver” was originally very limited in its meaning, referring to how units adopted different tactical formations—deploying from column into line, refusing a flank, forming into a march column, etc. Well-drilled troops were essential for executing a plan in the heat of battle, so maneuver was considered an important part of tactics.

It was Guibert, the French military reformer writing in the wake of the Seven Years’ War, who gave maneuver something approaching its modern meaning. He introduced the concept of the march-maneuver: a march undertaken in the presence of the enemy with the intention of securing some advantage. By marching in multiple parallel columns, each with a carefully planned order of march, an army could move faster—it avoided getting choked up at bottlenecks or the slinky effects produced in long columns—and also deploy faster. With such bold strokes, Guibert insisted, an army could lever the enemy out of even the strongest position, marching to attack on the flanks, from high ground, or in the rear. The meaning of “maneuver” thereby came to be associated with movements relative to the enemy.

It was in this context that he advocated a war of movement, not position (which he understood to include entrenched lines, not just the defense of fortresses). He blamed France’s recent defeat on their preference for positional warfare, arguing that this robbed them of the initiative and sapped their fighting spirit—he is considered to have lain the groundwork for fast-paced Revolutionary warfare.

Guibert’s concept was at base tactically-minded, focused on the enemy’s immediate disposition, but it was soon applied more broadly. Rapid marches to cut the enemy’s communications or lines of retreat were considered the height of skillful maneuver, forcing him out of strong positions without firing a shot. One writer spoke of such maneuvers that were “nothing but a matter of taking positions, without any question of disposition of troops, and owing nothing to training or any evolutions.”1 Maneuver was coming to be defined in relation to the enemy.

Maneuver in a Positional War

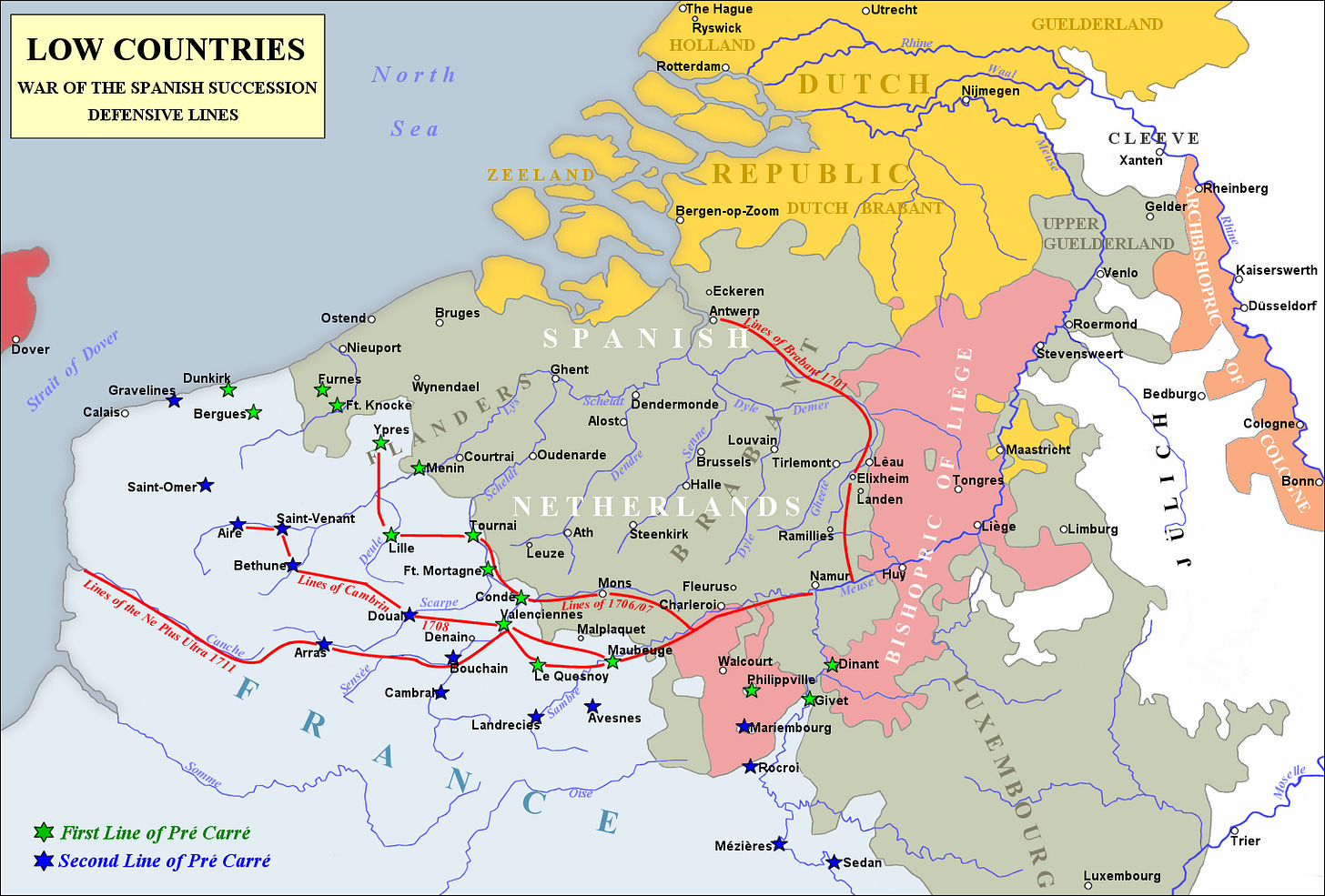

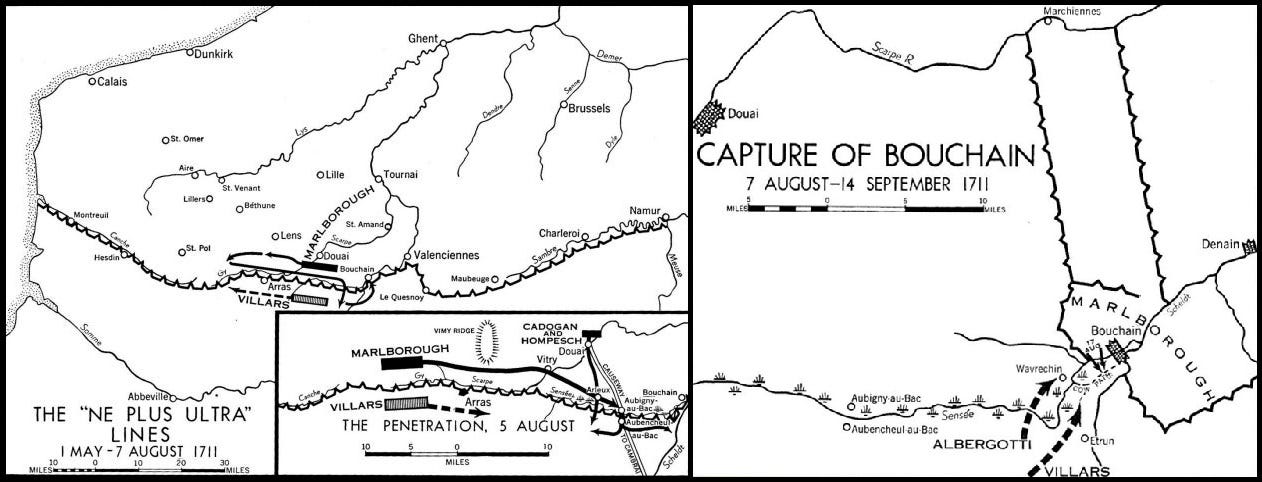

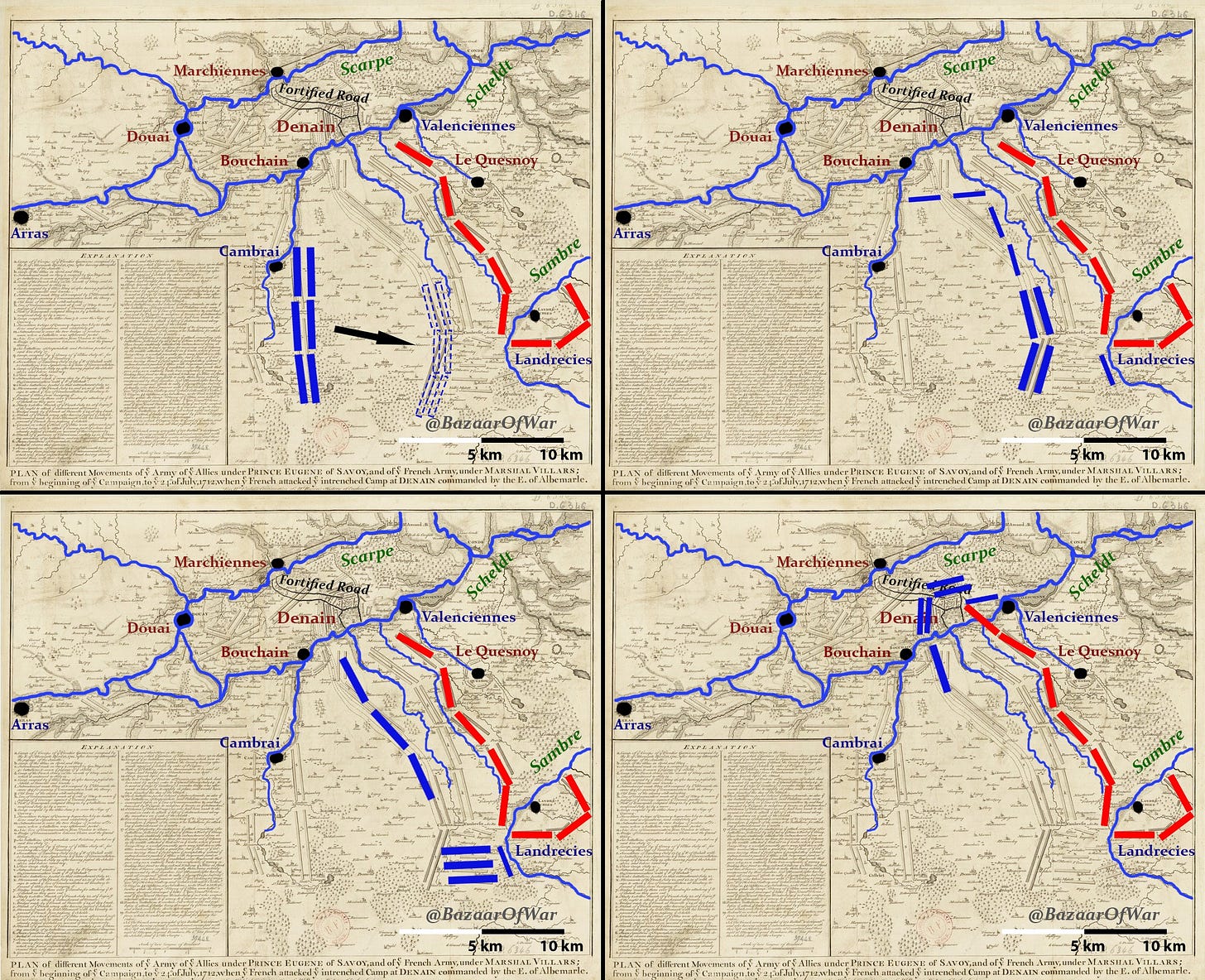

These sorts of maneuvers were most often associated with wars of movement, such as Frederick the Great’s many waltzes with the Austrians. But not wholly so. Prior to the First World War, there was no better example of positional warfare than the northern front in the War of the Spanish Succession. The Spanish Netherlands and French frontier were a dense array of fortresses, connected by long lines of entrenchments and river barriers. This made advances difficult, forcing the armies of the anti-Bourbon alliance to painstakingly reduce one fortress after another on their drive into France.

On two separate occasions, the Duke of Marlborough broke through French lines by a ruse: appearing to attack in one location, then rapidly marching elsewhere to cross a river or physically break through entrenchments. Yet neither of these maneuvers opened up the field to mobile action. They merely created a small window of opportunity to build entrenchments of his own, securing a lodgment that allowed him to besiege another fortress.

Marlborough had already made his reputation as a general by this point, having in 1704 marched 300 miles across Germany to stop the French at Blenheim. Aside from a few deceptions to conceal his intentions along the way, this was a straightforward campaign of rapid movement that aimed to meet the enemy in open battle—nothing like the maneuvering in his positional campaigns in the Low Countries.

So too on the French side. The year after Blenheim, the French marshal Villars skillfully blocked Marlborough’s attempts to bypass the defensive lines in the north. Then in 1712, when the Allies were on the verge of breaking through the last line to march on Paris, he slipped past them to seize their fortified camp at Denain, which guarded a river crossing to their rear. Their supply lines cut, the Allies had no choice but to withdraw, leaving Villars free to recapture a string fortresses. In a single stroke, he undid three years of losses and forced them to abandon the northern theater.

These historical examples help us ground maneuver in concrete terms. Villars’ gambit was maneuver by any definition, and was celebrated as such in the eighteenth century. But it reversed the usual order of things: rather than occupy an unexpected position to mount a favorable attack, he launched an unexpected attack to occupy a favorable position. This accomplished his aim, but did not change the pattern of the war, which remained firmly positional.

We should also note that though the war was positional to an unprecedented degree, it was not attritional. The Allies were attempting to secure their advance on Paris, while the French were trying to firmly beat them back. Position and movement only describe dynamics, while attrition and decision describe mechanisms of victory. Maneuver can be used in any combination of the four: this is true whether one defines it solely in terms of spatial relationships or takes a more expansive view.

Verbal Maneuvers

Coming back to the original question via this sweep through the past, we find ourselves in a better position to attack it. We see that maneuver is more often a tool that enables breakthrough, not the other way around; and once achieved, breakthrough does not necessarily restore mobility. The past century has taught us moreover that positional warfare is sticky: extended fronts make it easier for the defenders to fall back on their own lines of communication than for the attackers to sustain the advance; only after extensive attrition do deeper thrusts become possible.

The question then becomes how to exploit the brief windows of opportunity that maneuver opens up, not how to restore mobility as such—breakthroughs are not something to be worked toward in the blind hope of salvation. Specific objectives must be measured against the means available, whether that is to secure a strategic objective, destroy an enemy concentration, or simply occupy a more favorable position for inflicting attrition; it could even mean taking a single step forward in a relentless advance.

None of this is to raise anything new about the Ukraine War, nor does it suggest a way around the very real limitations that both sides face. It is only to point out how half-formed concepts can easily work their way into the discussion, often leading it astray. With clearer language comes clearer thought.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Turpin de Crissé, Commentaires sur les Institutions militaires de Végèce, vol. 1, p. 390.

This kind of reminds me of a tactic in some RTS games called basewalking. Basewalking is a way to get around a limitation in older RTS games that prevented you from building your buildings beyond a radius of your other buildings. Naturally, this would eventually allow you to build defenses all the way to your opponent's base.

As armies get bigger and logistics more complex, I think peer warfare more and more begins to resemble basewalking, troops being there to defend their sources of supply and prevent the enemy from making a fast break towards enemy lines. We could then see the whole war as a single siege between two walled countries, using troops, artillery, and standoff munitions as mobile walls that control by fire rather than obstruction, thanks to modern detection and signals intellgence. Political, economic, and social media maneuvering seeks to demoralize or starve out the opponent, while the battlefield turns into a hodgepodge of back-and-forth skirmishing, each side probing for defenses in the other's "wall".

"Siege of Nations Theory" has a ring to it.

I have always thought of it as the use of fire and maneuver, not necessarily in tandem but in coordination- fire paving the way for maneuver and maneuver putting fire in positions where it will be effective.