OIF Redux: Imagining the Iraq Invasion in the Present Day

What would the Iraq War look like if fought today? Technological developments since 2003 have swung hard in favor of the defense, raising serious questions about the viability of large armored thrusts. Ukraine war passing the two-year mark only emphasizes this, standing in stark contrast to the lightning three-week Iraq campaign.

Force Quality and Density

Technology was hardly the only reason for Saddam Hussein’s swift defeat, of course. His military had been hollowed out by the Gulf War and the intervening 12 years of sanctions. The US held an absolute advantage in airpower, which it could employ virtually unhindered on ideally-suited terrain. The Iraqi army, although large in numbers, was demoralized and poorly trained, and faced a restive populace—even when the Coalition was massing on the border, it was postured more towards suppressing internal uprisings than defending key chokepoints. Ukraine’s army, by contrast, was much more evenly matched and experienced from the past eight years of fighting, its IADS largely intact, and had the backing of its people (to say nothing of force quality differences between Russia and the US).

Another big factor was geography. Although both Iraq and Ukraine have vast open spaces, the two most crucial axes in the latter were far more constricted. The terrain northwest of Kiev is marshy, heavily wooded, and cut through with rivers, while the contested parts of the Donbas were already heavily fortified. In terms of area, the Russians made their greatest initial gains in the far more open south, east, and northeast.

Iraq was a different matter. Although the Tigris, Euphrates, and a few smaller rivers and canals were major obstacles, they all passed through open, hard-to-defend country which allowed multiple crossing points. V Corps was able to swing through open desert before closing in on Baghdad.

Put another way, the Coalition faced a much lower effective density of forces on its two main axes. If modern weapons/sensor combinations raise doubts about the possibility of breaking through prepared defenses, can operational mobility still be effective when it has room to maneuver?

OIF Redux

To get a better grip on the question, let’s imagine what the 2003 invasion would look like if launched today against a force comparable to Ukraine’s. In particular, we will follow the progress of 1st Marine Division, which advanced through the best-defended parts of Iraq on the drive to Baghdad.

1st MARDIV’s infantry regiments were organized into three combat teams: RCT-1, -5, and -7, each of which had a light armored reconnaissance battalion attached and two of which had tank battalions. The division formed the spearhead of I Marine Expeditionary Force, a corps-sized formation which also included 2nd Marine Expeditionary Brigade (Task Force Tarawa, basically half a division) and the British 1st Armoured Division, plus 3rd Marine Air Wing.

A better-equipped and more competent Iraqi Army would also require a larger invasion force. We will make the following assumptions about each side:

Iraq

Loyal populace. Part of what hindered the effective employment of Iraqi regulars in 2003 was civilian opposition in the overwhelmingly Shiite south, forcing the army to keep one eye on the populace even as it fought the Coalition.

Competent leadership. Even when the Iraqis had substantial forces on favorable ground, they were often employed poorly; we will assume by contrast that Iraqi leadership shows basic tactical sense.

Better air defenses. Up to a dozen S-300 batteries positioned around major cities, supported by older Buk variants.

Greater use of ballistic missiles (homegrown al-Samoud variants) and all classes of UAVs.

Coalition

Larger ground forces. I MEF has a minimum of four full divisions: 1st and 2nd MARDIV (with their since-cashiered tank battalions) and two full UK divisions.

Larger complement of artillery, engineers, and anti-air/cUAS systems.

Lots of UAVs integrated at every level.

There is also the question of the air campaign. Although the US is unlikely to ever launch a ground campaign without first suppressing its adversary’s IADS, air supremacy is not a luxury that most world militaries can count on. We’ll fudge our scenario a bit and assume the US invades before degrading Iraqi IADS, relying on UAVs to partially compensate for diminished air power. We further assume that the Iraqis only emplace their S-300s around major defensive positions, and that by the time ground forces have gotten to the rear of a defensive position, all SAM batteries in the vicinity will either have been destroyed by air and missile strikes or forced to displace (AD batteries are a different matter).

We’ll look at four episodes from 1st MARDIV’s account of the invasion: the opening border battle, actions around Nasiriyah, maneuvers between the rivers, and the crossing of the Tigris/final drive to Baghdad. In reality, modern weapons would likely change both sides’ entire concept of operations, but looking at each of these tactical scenarios in isolation gives us the building blocks to infer a broader operational concept.

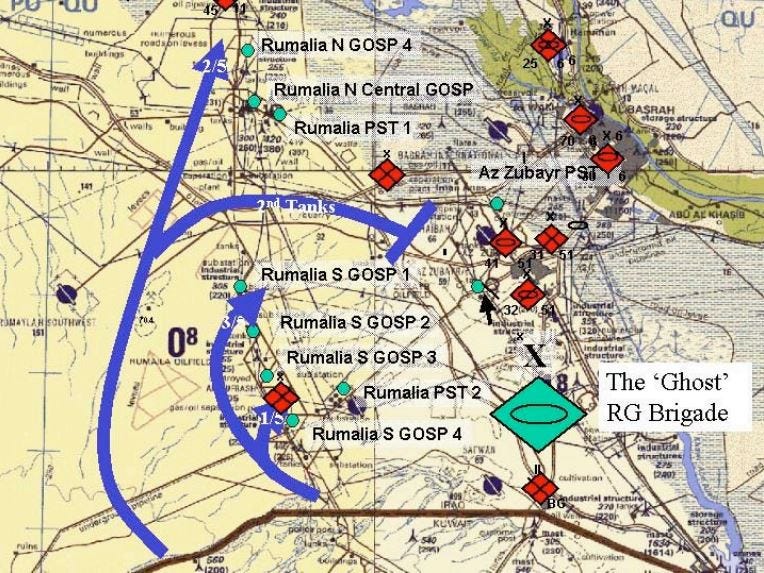

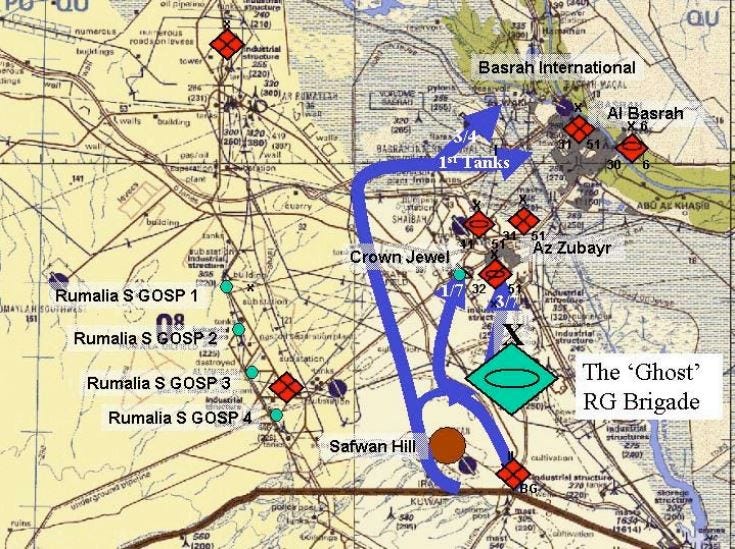

1. Crossing the Line of Departure

RCT-5 crossed of the line of departure on the evening of 20 March, supported by shaping fires which silenced Iraqi artillery. Two battalions swept around from the west and set up blocking positions: 2/5 facing the 6th Armored Division to the north, 2nd Tanks along Highway 8, cutting off the withdrawal of the 51st Mechanized Division along the border. They had traversed 70 km within 10 hours, setting up their positions around sunrise. The artillery battalion 2/11 followed soon after, setting up firing positions in the north oil fields to support them. 1/5 and 3/5 meanwhile secured the oil fields, which had been defended by a brigade from the 18th Infantry Division.

RCT-7 began its attack on the 21st from a breach site east of the oil fields, compelling large elements of 51st Mechanized to surrender. They hooked east to secure the Basra International Airport, and those Iraqi forces that didn’t surrender and weren’t destroyed retreated into Basra. RCT-1 meanwhile crossed the border west of RCT-5, clearing the way west along Highways 1 & 8 to secure the division’s advance. The UK’s 1st Armoured Division relieved the rest of 1st MARDIV the next day, going on to attack Basra as the Marines headed west.

Looking at this through the lens of our hypothetical, the greatest threat to the enveloping forces would have been a simultaneous attack by the withdrawing 51st MD supported by the 6th AD from the north. This area would still be covered by Nasiriyah and Basra’s long-range air defenses, and the possibility of medium-range AD renders uncertain the use of rotary-wing—the forward battalions’ primary means of fire support.

There is no solution to this but mass: a full division would have to attack on either side of the Rumaylah oil fields with heavy UAV and artillery support. The area around the highway junctions is very likely to be covered by long-range fires, so there would be a race to dig in before daybreak. Working in the Coalition’s favor, the 51st could be targeted by HIMARS strikes from Kuwait during the ground forces advance. 6th AD is especially vulnerable to interdiction, as it had to cross the Euphrates over a single bridge. The greatest risk would be to RCT-1, which we assume would still be clearing the highways to the west. Its advance would be limited until it could be allocated more fire support, and digging in would be absolutely critical.

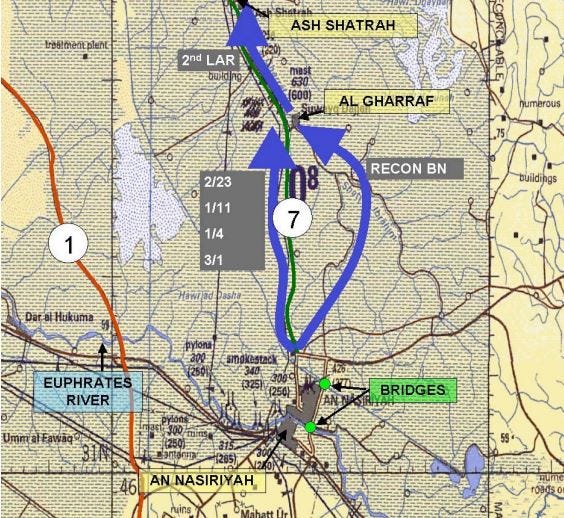

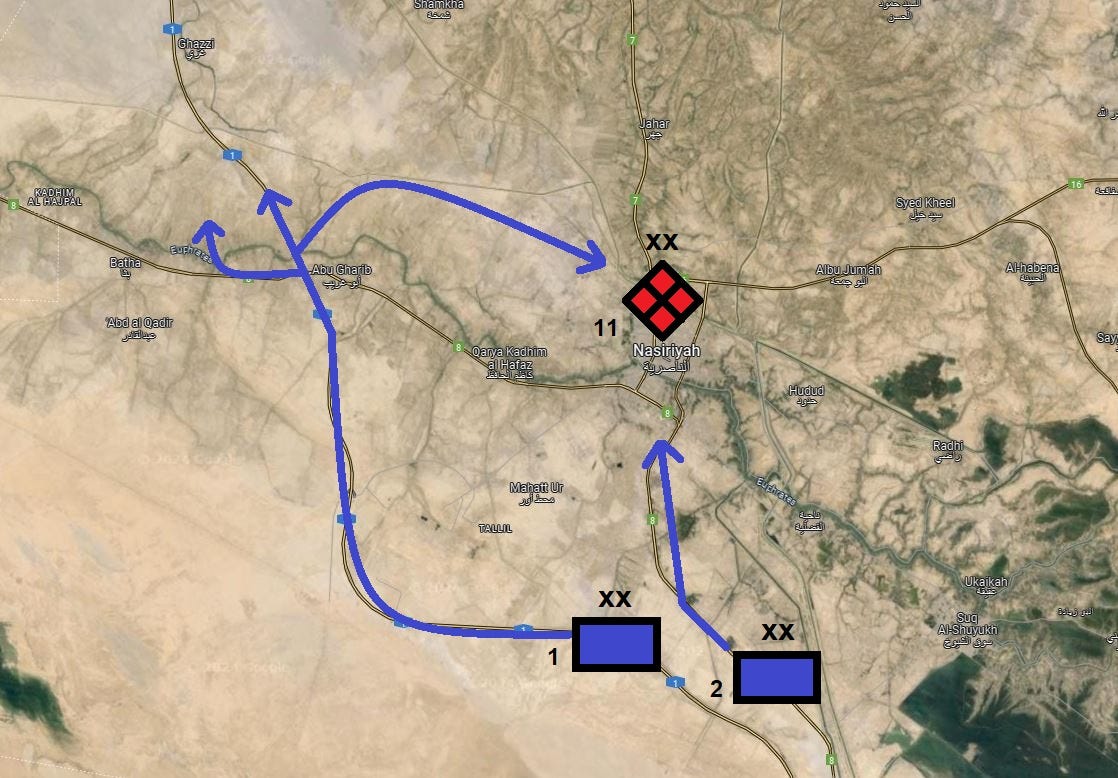

2. Bypassing Nasiriyah

The next major obstacle was the Euphrates. Several bridges passed through Nasiriyah, so securing that city would be critical for sustaining 1st MARDIV’s advance. The Iraqi 11th Infantry Division was positioned east of Nasiriyah, while Saddam’s loyalist Fedayeen paramilitaries defended the city itself. 25 km to the west was the Highway 1 bridge, however, which would allow the majority of the division to bypass the city entirely. This bridge was not yet complete, so engineers had to improve the approaches on either side before 1st MARDIV could begin crossing on 23 March.

That same day, TF Tarawa began its assault on Nasiriyah. It was decided to push RCT-1 through the city even as the fight for control was ongoing. A refueling point had been established ~50 km south of Nasiriyah so that the Marines could reach their next objectives before having to refuel, and on the night of 24-25 March RCT-1 passed through the city on Highway 7. RCT-1 faced heavy resistance inside and just beyond the city, but was able to break through to the north.

A competent defender with the civilian populace on its side would have been able to use the Euphrates to great effect. Positioning the Iraqi 11th ID in and around Nasiriyah would have made it a much more formidable obstacle. This also would have also imposed difficulties on crossing the river elsewhere. In the first place, it would deny the use of Highway 8 on the approaches to the crossing site west of the city, as this route passes through the southern outskirts of Nasiriyah, creating further congestion before the river.

Then there is the question of the crossing itself. Assuming the Highway 1 bridge had not been destroyed in advance, it would constitute a very dangerous chokepoint. Although this was outside the range of most artillery in Nasiriyah, it would be vulnerable to drones and ballistic missiles. This would require, at a minimum, engineers to lay another bridge further upstream under the protection of air defenses.

Once across, elements of 1st MARDIV would hook around to help 2nd MARDIV secure Nasiriyah. There are few paved surfaces in the immediate vicinity and the area is cut through with canals and irrigation ditches, so this might require substantial engineering assets. Artillery could be airlifted by low-flying CH-53s. With the city cut off to the north, air defenses would be forced to displace, allowing air to operate more freely and shut down any long-range fires still active—a top divisional priority. Coordinating the two elements in the face of the missile threat would be a critical challenge during this phase.

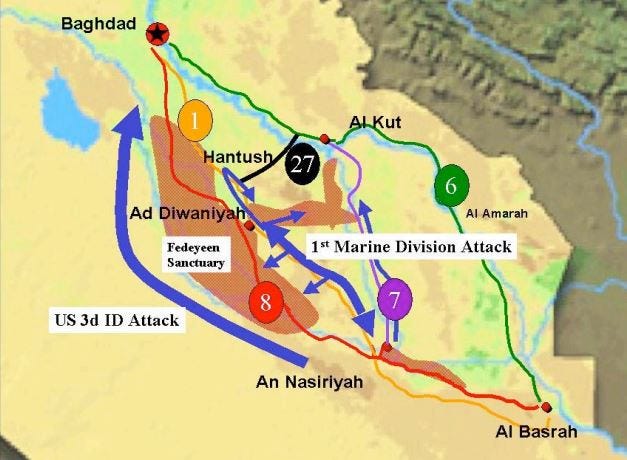

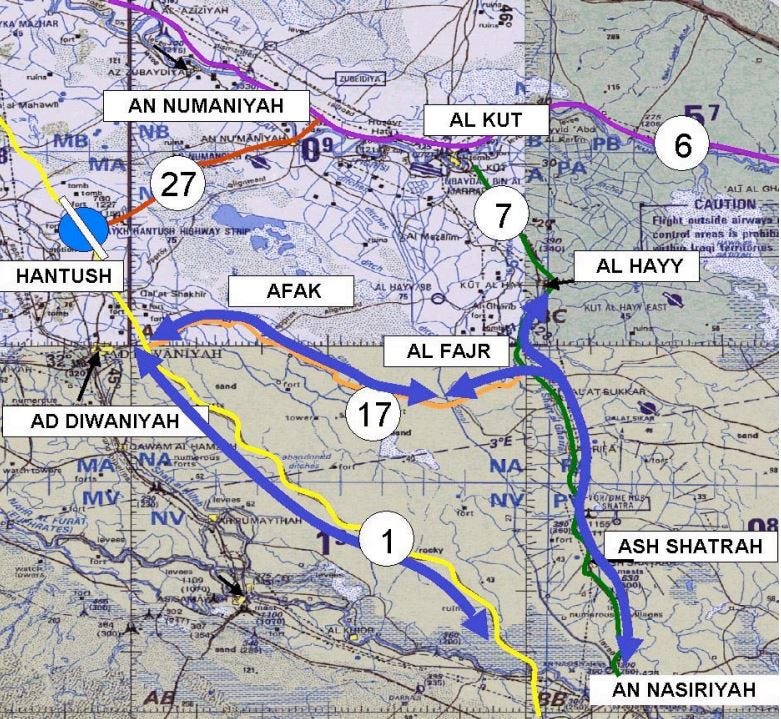

3. Between the Rivers

The way was now open for 1st MARDIV to proceed directly to Baghdad, with only the Republican Guard’s Medina Division standing in its way. Iraq’s capital straddles the Tigris, however, and the plan called for I MEF to attack from the east while the Army attacked from the west. This entailed another river crossing for the Marines, which in turn required the capture of Kut, defended by the Republican Guard’s Baghdad Division.

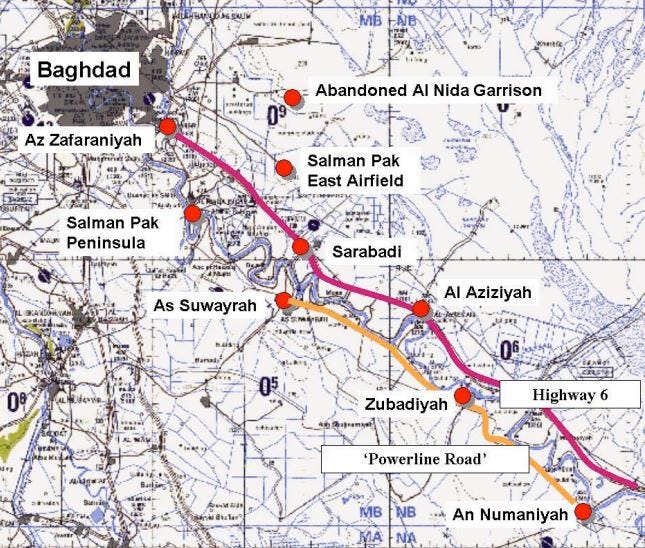

RCT-5 and -7 would proceed up Highway 1 as far as Hantush Airfield, a section of the highway that had been converted into a landing strip—this would be turned into another resupply point. RCT-7’s reconnaissance battalion would then continue up the highway as a feint, preventing the Medina Division from redeploying against V Corps, while all other elements turned northeast up Highway 27 to cross the Tigris near Kut. RCT-1 would meanwhile continue up Hwy 7, eventually linking up with the rest of the Division along the river.

Things were slowed down by various points of friction. Although lead elements of RCT-5 raced ahead up Highway 1 on the 23rd, relying on air to destroy enemy armor, and most of RCT-5 and -7 were over the river by the end of the 24th, a major sandstorm kicked up the following day. This ground forward progress to a halt around Diwaniyah. On 27 March 2/5 pushed ahead to seize Hantush Airfield, but fierce Fedayeen resistance combined with an attack by tanks and BMPs around Diwaniyah forced it to withdraw.

RCT-1 meanwhile fought its way through Nasiriyah on the night of 24-25 March, getting into a tough fight with reinforcements streaming south into the city. It then proceeded deliberately up Hwy 7, attacking potential ambush positions then occupying them with infantry to secure the route for all follow-on forces. It then seized Qalat Sikar airfield at the intersection of Hwy 7 & 17, providing a much-needed resupply point since the ground route through Nasiriyah was not yet secured. The two halves of 1st MARDIV spent the next several days securing their respective routes, and Hwy 17 was eventually cleared on the 29th, securing RCT-1’s ground lines of communication.

Finally, on 31 March, the Division proceeded to the Tigris: RCT-5 seized Hantush airfield then continued up Hwy 27 toward Numaniyah, while RCT-1 attacked up Hwy 7 toward Kut. It faced artillery fire and other resistance from Baghdad Division elements in Hayy, 40 km south of Kut. An attack from the south and west supported by rotary-wing caused the Iraqi defenders to flee, abandoning their equipment.

The scheme of maneuver on the far side of the Euphrates is heavily dependent on how the crossing of the Euphrates itself is conducted. As we have already seen, RCT-1 could not simply press through a well-defended Nasiriyah—indeed, it would likely have to participate in the attack via the north bank. This would also create enormous congestion on Hwy 1, which now has to accommodate all of 1st MARDIV—as it was, it took the better part of two days to get the division across in 2003.

Things are further complicated by the presence of Diwaniyah, which can easily range a long segment of Hwy 1 with artillery. This includes the junction of Hwy 17, the first major road heading east from Hwy 1. The Fedayeen in 2003 posed enough of a problem that progress had to be delayed for several days; a strong garrison in Diwaniyah could therefore completely halt I MEF’s forward progress until either it or Nasiriyah is reduced. The Medina Division was the only sizeable formation guarding southern approaches, and it had to simultaneously defend other avenues of approach, but it could easily throw a brigade into the city and send further reinforcements by three separate southbound highways.

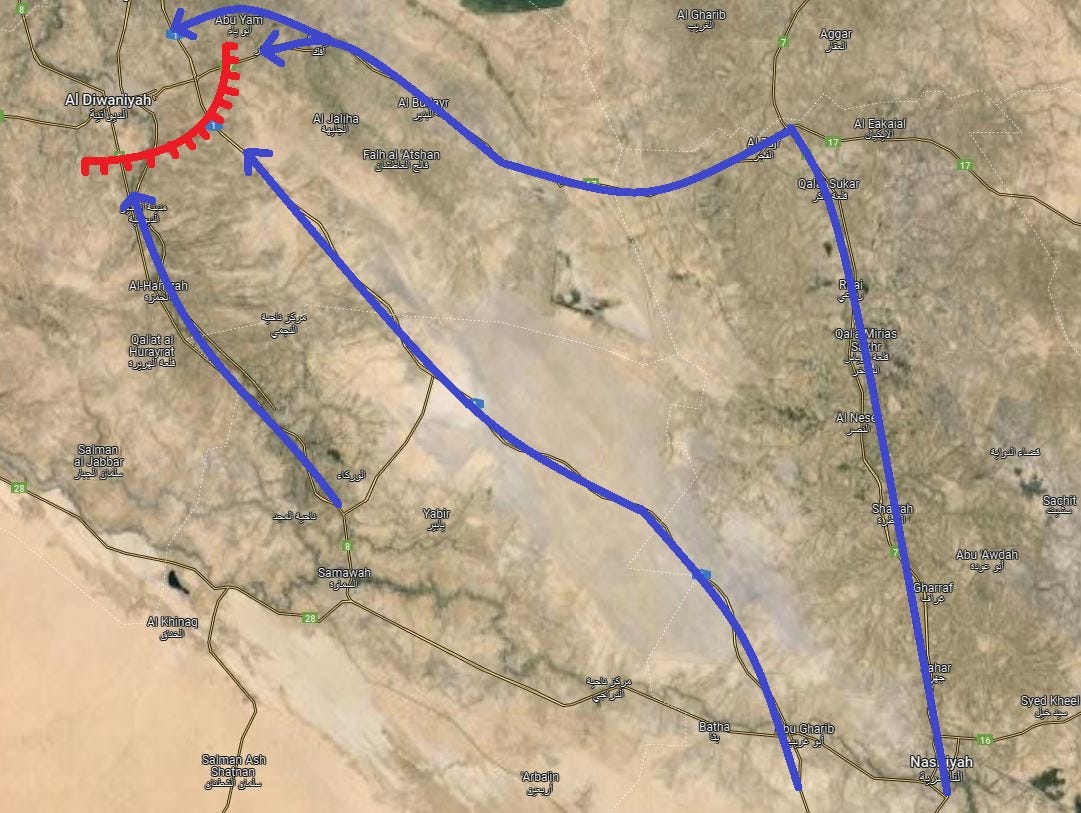

The easiest way for 1st MARDIV to solve both problems would be to secure a third crossing point of the Euphrates via Hwy 8 at Samawah. In 2003, the Army’s 3rd ID bypassed Samawah while travelling along the southern bank of the Euphrates. In our scenario, it would support RCT-7’s attack on the city from the south, while RCT-5 isolated it from the north (likely defended by a brigade from the 11th Infantry Division positioned in Nasiriyah). Use of aviation would still be somewhat restricted by the proximity of air defenses in Diwaniyah.

Once Samawah is secured, the two RCTs would proceed up Hwy 8, while RCT-1 eventually joins up Hwy 1. Depending on how long the fight for Nasiriyah lasts, 2nd MARDIV might be able to send help along Hwy 17—otherwise, 1st MARDIV faces a difficult fight to get around the flanks of the defenses. Only once these three cities are captured can 1st and 2nd MARDIV proceed to the Tigris.

Beyond operational considerations, there is the tactical question of traversing the open ground between the Tigris and Euphrates with open flanks. Although the country is relatively flat and open, it is cut through with ditches, gullies, groves, small settlements, and other cover and concealment. Much of this area would also fall under the AD umbrella of Kut or Diwaniyah, so 3rd LAR’s route reconnaissance outside of artillery range would simply not be possible.

An even bigger challenge would be dealing with drones. Lead elements would have to be equipped with plenty of cUAS and EW equipment, while Marine UAVs fly parallel to the roads to seek out radio signatures and call in fires. An even more thorough version of RCT-1’s strongpoint tactics would have to be adopted, with men and vehicles digging in at many points along the way.

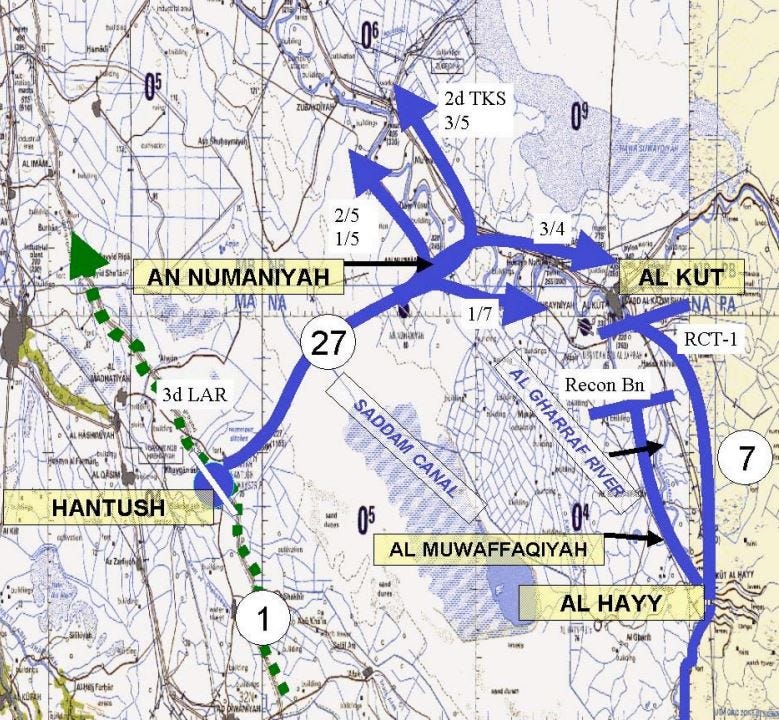

4. From the Tigris to Baghdad

1st MARDIV was able to rapidly cross the Tigris. On 1 April RCT-5 seized a bridge over the Saddam Canal, about halfway up Hwy 27 from Hantush to the Tigris, destroying enemy artillery with air and ground fires. As it and RCT-7 advanced to the river, calling in fires on defenders around Numaniyah, engineers put up another bridge over the canal to secure supply lines. RCT-1 meanwhile advanced on Kut from the south, while to the west V Corps crossed into I MEF’s battlespace to attack the Medina Division, securing both corps’ flanks as they advanced on Baghdad.

On 2 April RCT-5 secured the crossing at Numaniyah, ~35 km upstream from Kut, allowing RCT-7 to advance on the latter from both banks. The attack was launched the following morning. Preparatory fires over the previous days, combined with an attack from several directions, reduced the city by that afternoon.

1st MARDIV now faced the three brigades of the Republican Guard’s Al Nida Armored Division and Fedayeen units. Their armor and artillery had already been much reduced by air strikes, although they occupied strong positions along Hwy 6 on the north bank of the Tigris, and other units had been recalled from the north for the defense of the capital. I MEF wanted to push through this cordon quickly in order to deny them the chance to prepare defenses within the city. This meant pushing RCT-5 up Hwy 6 before Kut was even reduced. On 3 April they began their advance, passing by vehicles and guns which had either been destroyed in air strikes or simply abandoned.

They first encountered resistance around Aziziyah, limited to small arms at first but increasing in intensity. Within the city, 2nd Tanks engaged several tanks and AD guns, which they destroyed with the help of air. 3/5, which was following in trace, encountered heavy resistance from infantry in prepared positions along the road. The battalion then entered Aziziyah and cleared it. The rest of RCT-5 moved on the south bank of the river, supporting the attack on Aziziyah; the bridge there was too unsound to allow them to cross, however, so they looped back to Numaniyah to rejoin the main body. The airfield at Aziziyah was captured, allowing resupply.

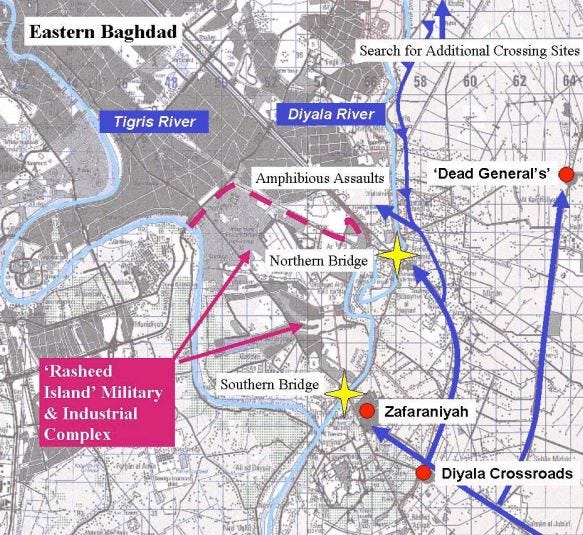

2nd Tanks continued in the lead on 4 April, followed closely by an artillery battery and 3/5. They reached their objective of a crossroads near the Diyala River, the last obstacle before Baghdad, but faced fierce resistance from Fedayeen and foreign fighters along the way—2nd Tanks lost an Abrams. The next day revealed that an entire brigade of the Nida Division had abandoned its equipment on the east bank of the river. RCT-5 and -7 spent the next several days skirmishing with Iraqis on the far bank of the river, securing their rear areas, and reconnoitering crossing sites. The Iraqis had damaged the two bridges in the area, blowing out a span on each. On 7 April, under enemy artillery fire, engineers from RCT-7 lay bridge sections across the damaged spans and a ribbon bridge at a nearby site. Further north, AAVs from RCT-1 launched an amphibious assault to clear out Iraqi concentrations on the opposite bank and allow another ribbon bridge to be laid. With this, 1st MARDIV was able to cross the river and establish a cordon around eastern Baghdad.

Al-Kut in 2003 resembled Nasiriyah in our imagined scenario: one force assaulted from the south, while another bypassed it to the west and enveloped it. The crossing would be made easier by the fact that the bridge at Numaniyah is farther upstream from Kut than the Hwy 1 bridge over the Euphrates is from Nasiriyah (although this would still probably have to be supported by engineer-laid bridges).

The real challenge would lie after that point, as the entire approach to Baghdad would be covered by the capital’s air defense umbrella. This would require a much greater concentration of artillery to compensate, which in turn would probably require a division on each side of the river to provide mutual support—much as RCT-5 divided forces up to Aziziyah. Canals and marshy terrain would make movement on the south bank especially difficult, and the need for mutual support would thereby slow the northern division. Compounding this, the terrain provides ample opportunity for ambushes from prepared positions supported by fires. Without air power compelling defenders to abandon their positions, this would be a slog.

The final would lie in crossing the Diyala River. This would likely proceed much as in 2003, albeit slower and more deliberately. Amphibious forces would have to clear a deeper area on the far bank, and ferries may even be needed to bring armor over, before the engineers could lay sections across the destroyed spans and set up their own bridges. To address the threat of artillery targeting the bridges, the actual crossing might have to await an extensive SEAD effort to open the skies to UAV surveillance, and additional crossing sites might have to be established farther north.

Conclusion

All told, this thought experiment does not bring any great surprises. A well-executed defense integrating drones and long-range fires with an intact IADS would require a much larger attacking force, equipped with plenty of artillery, drones, and engineering assets. Obstacle crossings would have to be conducted more deliberately across a broader front, and the fighting would be much more difficult throughout.

In 2003, RCT-5 moved an average of 35 km/day from the line of departure to the outskirts of Baghdad, advancing 520 km in 15 days. This pace remained remarkably consistent both in periods of constant fighting—lead elements took two days to advance 70 km from Numaniyah to the Diyala River—and during the periods of greatest operational complexity, such as the 8 days it took to cross ~250 km from the south bank of the Euphrates to the north bank of the Tigris.

Such speeds could obviously not be expected in our scenario. Modern weapons and better Iraqi tactics would make the combat much more difficult, slowing everything down. Extended spearheads that could not get air support would have to rely instead on mutually-supporting lines of advance. This would slow things down even further as setbacks in one area delay efforts elsewhere—there could be no rapid push up Highway 1 or through a contested Nasiriyah.

At the same time, this emphasizes how operational art is even more important than in 2003. Tactical difficulties are more easily dealt with when they can be bypassed and enveloped. Although that takes longer than simply charging through, in the long run it is usually faster and easier. This same speed vs. efficiency tradeoff was on display in the opening weeks of Russia’s 2022 invasion, and partially explains its failure to win a quick victory. Rather than concentrate on a giant double envelopment in the Donbass, they dissipated their forces on the open plains of their right flank, and on the left got bogged down besieging Mariupol; by the time they resumed the advance weeks later, the Ukrainian defensive line had firmed up.

For all the difficulties that modern weapons impose on mobility, their effects are highly context-dependent. I remain skeptical of the prospect of true breakthroughs against well-equipped defensive lines, but the opening phase of a large-scale war is a different matter. The chaos and confusion of the opening weeks create gaps that could yet be exploited with bold armored thrusts—so long as the terrain allows it.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have access to occasional exclusive pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

I was unlucky enough to be in both Desert Storm as an infantryman and OIF 1 as a pilot. In my experience what most overlook is the discipline and overall human quality of a western army over a west Asia army. Iraq had the 4th largest army on the planet and top tier Soviet equipment in 1991, and we went through them like shit through a goose. Mostly because of devastating air power. There was less of a prep for OIF but more higher level leaders had been in Iraq the first go around. Remember during DS most of the generals were Vietnam vets. As a side note I was opconed to 3rd ID with an infantry BCT from the 101st ABN. 3rd ID absolutely laid waste to everything. I’m a light infantry/airborne guy at heart, but watching a mechanized division go to work from a helicopter pilots point of view was awesome to say the least. I think only the Russians or Chinese could stop something like that. Problem is it takes a month to get that kinda unit into place.

Great read as usual!

Guys, good questions, but Ben has undertaken a challenging task here and worked through it in my opinion brilliantly. Very hard to make these kinds of comparisons and decide what variables can be controlled and which must be adjusted to make the initially apples-v-oranges contrast a workable apples-v-apples comparison, without creating incoherent scenarios. He bent factors in favor of the defense but found that nonetheless, modern offensive forces and op-art would prevail. This is an excellent hypothesis that bears more serious testing.

That requires wargaming. The appropriate tool is "Gulf Strike" (Mark Herman, Victory Games, 1983), ideally the 3rd ed. (later release, a bit expensive these days). That one modelled a Soviet invasion of Iran, later expanded to include Iran-Iraq and Desert Shield, developed for Andy Marshall at DoD/ONA.

Then test it to ensure it accurately replicates both the Iran-Iraq War (firepower-attritional sludge match) and the maneuver-warfare blitz during the 1990-91 Gulf War. Then amend it to reflect the situation and forces employed during the 2003 invasion. One would have to modify the forces and create unit counters, but that's all part of serious analysis.

We'd have to review the adjustments for suitability, judgment being required in any such work. Remember that Ben's deeper purpose here is to explore the narrative that in contemporary/future land warfare, advantage has slipped back toward the defensive side for the first time since 1939. He rightly questions that premature proposition, and approaches it with an excellent case-study research design. I think we all can agree that that the proposition warrants hard analysis, and his hypothesis development effort above providesis an excellent first step toward scientific testing.