Pulsing From the Depths: The Problem of the Rear Area in Offensive Operations

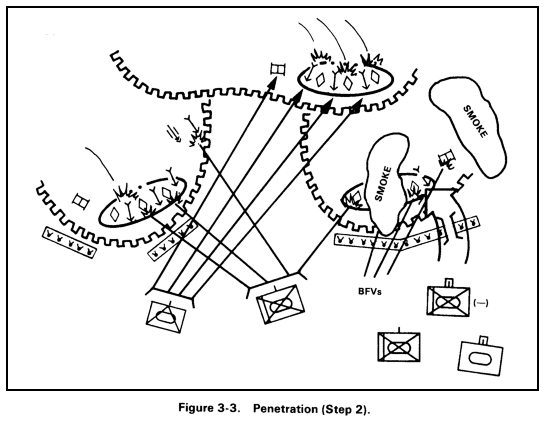

It is a basic principle of combined arms that, by concentrating a variety of different fires, one can simultaneously increase the odds of success while providing maximum protection for troops at the point of the attack. Layered fires, jamming, spoofing/decoys, and interdiction strikes in depth represent pulses of combat power that support the ground assault while making it hard for the enemy to strike assaulting troops; several pulses delivered in close succession increase the chance of a breakthrough or other disproportionate effect, while making it very hard for the enemy to reconstitute and counterattack. Offensive and defensive functions are inextricably linked.

From the planner’s perspective, the division of major operations into phases reflects the need to assemble the necessary combat power for each subsequent pulse. Units must resynchronize their efforts after every phase: by consolidating upon an intermediate objective, bringing up support, pausing to let others get into position, etc.

Traditionally, this assumes that, outside a relatively narrow band along the line of contact, units can operate in relative safety between pulses. Units coming up from the rear cannot be targeted except via deliberate pulses on the enemy’s part (e.g. an interdiction strike packages), while those at the forward edge of the battlespace occupy positions that are defensible against any immediate threat.

Threats in Depth

Long-range fires paired with persistent surveillance alter many traditional assumptions. They require far more resources to adequately suppress around even a limited objective, leading to the kind of incrementalist assaults we see in Ukraine. It is nearly impossible for larger formations, as currently organized, to move to contact and consolidate upon an objective—that would likely require far more engineering equipment than any army currently has.

But long-range fires also pose a threat in depth: to troops staging for an operation or simply moving to the front. Although attrition in rear areas is much lighter than that suffered by, say, infantry stranded mid-assault without artillery support, it also takes place over longer timescales during which losses can mount.

Once again, these pressures favor incrementalism. Supplies and troops move forward in a trickle, building up combat power only gradually. For routine resupply and troop rotation, this can be abetted by combinations of passive and active measures that are already used to one degree or another: a network of hardpoints connected by fortified and camouflaged corridors, with bursts of jamming and heightened AD alert during movements—a series of micro-pulses up to the front.

Surging Forward

But preparations for larger operations are more difficult to mask. Ukraine’s 2022 Kharkov offensive is the only really good example from the current war, and only saw as much success as it did because both sides had depleted the sector (Ukraine attacked with only about 9,000 troops) and left it unfortified—a mistake neither side is likely to repeat. Moreover, it does not solve the problem of exploiting initial success: if the enemy retains substantial long-range strike capability, he can delay or disrupt follow-on forces while containing the imminent threat (precisely what such weapons were originally developed to do).

This is not an entirely new problem. One of the less celebrated episodes of the Battle of France was the attempt by Allied aviation to contain the German bridgehead at Sedan after their initial breakthrough. On 14 May, the Allies directed a number of bomber sorties to destroy the pontoon bridges across the Meuse and cut off the Panzer divisions that had already crossed. The Germans were aware of the danger and emplaced an enormous battery of over 300 flak guns around the bridges while surged three fighter wings to the area.

Ground fire disrupted Allied bombing runs while German fighters brought down a large number of their aircraft. In total, the French and British suffered over 50% losses while inflicting minimal damage on the pontoons. The bridges were less than ten kilometers behind line of contact on the 14th—hardly in the Germans’ operational depth, but far enough behind the front line that their ground fires could not protect both at once. Only the concurrent surge of fighters made it possible for them to defend the entire area.

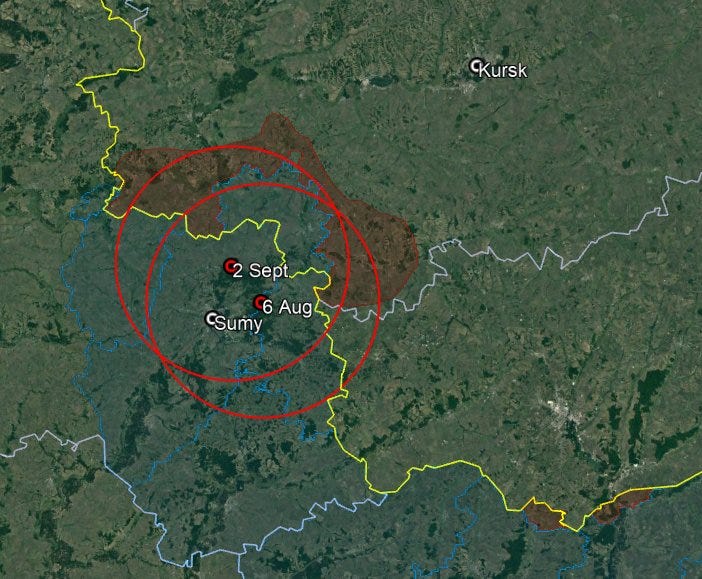

Longer-ranged weapons make this an even tougher problem, but there are possible solutions. Depending on the geometry of the battlespace, forward air defenses could act as a barrier to all long-range fires. During Ukraine’s incursion into Kursk, for instance, it appeared they pushed out their air defenses around Sumy to protect advancing forces while still covering the city.

But this is not always possible—say, when the attacker is pushing into a salient. EW and air defenses might have to be deployed everywhere that troops are on the move or in the attack. This becomes an especially vexing question when faced with inevitable resource constraints on high-value systems. Follow-on waves might have to move up into the first echelon’s staging areas just as it is moving out—a sort of inchworm advance. Or, coverage might have to be phased by axis, with SAMs and other systems redeployed to support different sectors every so often.

Beyond Breakthroughs

All this is to say, that rear-area security is yet another wrinkle in planning for offensive operations. Even if commanders in future wars figure out how to break through prepared defensive lines, sustaining that momentum will be a separate problem in itself.

The next major ground conflict could well see new technologies that partly offset these difficulties. Passive measures might even ease the burden on limited high-end systems—especially if militaries take seriously the task of creating fortified corridors throughout their own operational depth. But no matter what, these sorts of considerations will occupy considerable planning efforts.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Technically and historically fascinating! And very timely.

I don’t think recall ever using the description “pulse” before. It was perfect for helping understand the points. Have I been frozen in time?