The Future of Armor: Going to Ground

A recent piece from RUSI has provoked debate over the future of armored vehicles, examining how tanks can be adapted to the modern battlefield. It makes the case for preserving the main battle tank at the core of British force structure, comparing them to alternatives such as motorized/dismounted forces and IFVs. Although the discussion is tailored to the particular needs of the UK, most of the considerations hold more broadly.

It is equally important to approach the question from the opposite direction, to see how mobile formations will operate on the future battlefield—or, indeed, whether they are even viable. A clearer concept of employment makes it easier to weigh the protection-mobility-firepower balance for individual platforms. I have argued elsewhere that the combination of long-range precision fire and persistent surveillance may well have killed operational maneuver for the next few decades, and that the chief role of mobility may rest in bringing forces up onto line. It is entirely conceivable that ground combat may even be dominated entirely by artillery and infantry, with IFVs employed only as short-haul battle taxis for the final assault. So the question becomes, what can we expect not just of tanks, but of armor in general?

On the March

Mobility has always been the best protection for AFVs outside of combat, but modern weapons negate this. Precision rounds and more advanced UAVs can destroy tanks in motion, while conventional rounds and even FPV drones are effective during halts. When aided by persistent UAV surveillance, a competent defender can ruthlessly attrit a column on the move, limited only by the number of guns and launch systems available. One solution proposed in the paper is investing in shaping measures:

Critically, for heavy armour to be effective and survivable, the combined arms force as a whole needs to be able to conduct effective shaping of the battlespace to prevent saturation by enemy UAS and precision fires, and to be able to create sufficient uncertainty through deception that these enemy capabilities cannot target and attrit ground combat formations for decisive effect. (p. 41)

It is hard to imagine how this can be done reliably, however. With increasingly integrated C4I systems, even a single sensor or observer can enable targeting—it is effectively impossible to disrupt the enemy’s kill chain except in a limited, local way. Persistent surveillance reduces the advantage of deception once an operation is underway, as the enemy can eventually discriminate and engage targets. Nor is EW likely to be a solution: supposing that it were possible to blanket the battlespace with jamming, autonomous munitions will likely make these completely obsolete in the not-too-distant future. To even consider shaping operations of this magnitude would moreover require air superiority of a type only witnessed in Desert Storm.

Taken together, shaping operations promise to be no more effective than the preparatory bombardments of the First World War: the enemy only has to wait them out under cover. In order for armor to remain viable, something must therefore be done about its vulnerability on the march. There are two sides to this: suppressing enemy fires and organic protection. Of these, suppression is the simpler problem in principle because it can be done independent of the mobile formation itself. Theater air, missile, and EW assets can be aggressively employed against enemy drones, ground stations, radars, and artillery along the line of march. Even if destruction of these assets is beyond reach, this can slow down and degrade the targeting cycle.

Force protection is trickier. As the paper acknowledges, any mobile formation must have organic EW, SHORAD, and counterbattery fires. But every new capability puts more vehicles on the road and brings additional logistical requirements, the bane of mobility. And this protection need not be perfect, as the very justification for mobile warfare is that by accepting higher losses in the short-term, the ultimate cost is much cheaper. The challenge for planners is to strike the balance between acceptable protection and avoiding excessive delays.

Under Cover

Some delays are unavoidable, however, which can leave armor dangerously exposed. Organic defenses cannot protect against most long-range fires, while suppression is resource-intensive and cannot be carried on indefinitely. The simple conclusion is that tanks must begin to act more like infantry. The old truism that tanks fire between movements while infantry moves between firing positions. On longer movements, armor may now have to move from one protected position to another—in short, by constructing marching camps.

What would this look like? At a minimum, vehicles would require some form of top-cover when stopped for any length of time. This would disrupt the targeting of anti-tank artillery, lessen damage from conventional artillery, and protect against simple FPV drones. These would not have to serve as fighting positions, so they could be fairly rudimentary: existing hardened structures, improvised structures built from modular parts, or excavated tunnels.

All of these present problems. Suitable structures are not likely to be found in sufficient quantity, while the other options require time and specialized equipment to prepare. Nevertheless, engineering units following close behind the lead elements could prepare expedients, such as a quickly-assembled frame topped with Hesco gabions or packed earth.

Excavating a covered position is another possibility, but presents problems of its own. An M1 Abrams, for example, occupies about a rectangular box of about 100 cubic meters. Just to move that quantity of earth would take upwards of an hour for a typical engineering vehicle, not to mention the difficult of excavating horizontally underground and the extra volume needed for the entrance. A possible solution is to use improvised top cover over a trench.

The biggest obstacle is time. A typical brigade-level engineer company would require several hours to build shelters for a company of tanks, during which the latter could neither take cover nor continue to advance. To solve this, AFVs themselves can be equipped with dozer blades to assist, and engineers can use specialized equipment, such as what Ukrainians and Russians have been using to construct fortifications over the past year.

Sustaining the Push

Although it is feasible in principle to provide cover on the march, doing so for a major operation involving thousands of vehicles is an enormous challenge. Every movement of the lead element must be carefully planned and executed, then follow-on units must quickly rush forward to sustain the advance. At best this looks like an inchworm steadily advancing, at worst like a chaotic slinky. A simplified order of march, showing only the first of each unit type, might look like:

Armor

SHORAD

Engineers

Artillery

Sustainment

HQ

SAMs

This requires considerable fire support and engineering assets at every echelon. Each serial would have to contain its own air defense and counterbattery capabilities, or ensure that it is moving within the coverage of others. One advantage is that follow-on units can expand and improve the positions dug by preceding units, creating a fortified corridor through which supplies can be pushed forward. If well executed, this process of continuous entrenchment can avert a desperate scramble to protect forces later on.

Combat Worth

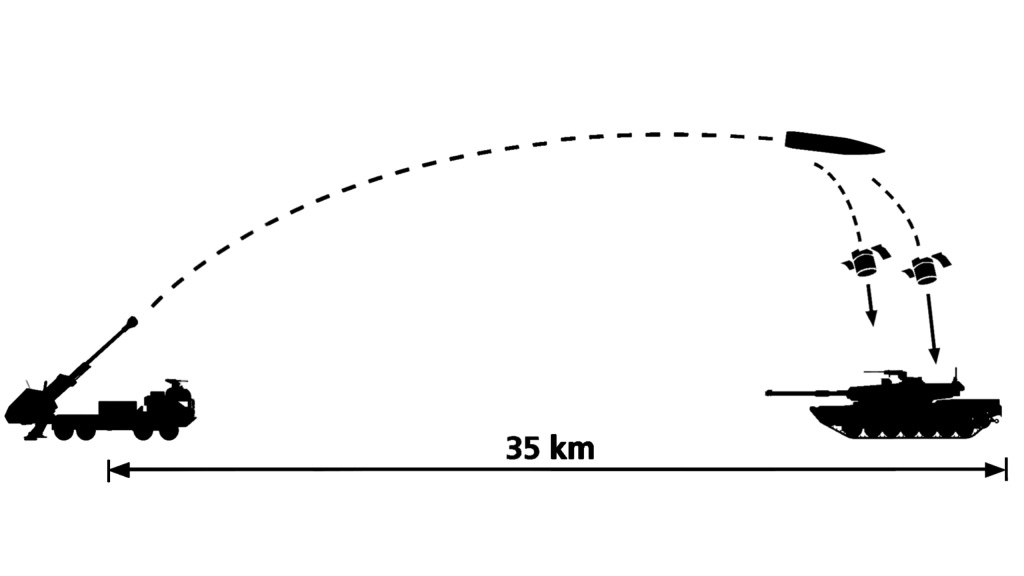

At a certain point, the advance is bound to hit stiff resistance, which brings us at last to the viability of armor in combat. Beyond the omnipresent threat of precision fires, there exists the more localized threat of ATGMs, which are bound to defend any target worth attacking. Tanks have always faced such threats—antitank guns in the Second World War were a greater tank killer than other tanks—but the cost ratio of ATGMs to modern tanks is now very unfavorable. The question comes down entirely to whether cost-effective countermeasures can be developed against them.

This is where it is useful to look at how the force structure will evolve as whole, not just individual vehicles. As I have argued elsewhere regarding helicopters, protection is likely to be separated from vehicles in the future. A screen of drones capable of intercepting incoming missiles could protect an armored unit much more effectively than APS mounted on individual vehicles, and the standoff would moreover reduce the risk to accompanying infantry. Variants could also be designed to take out smaller FPV drones that get to close. Defensive drone screens are likely to become standard for any unit in the open, as essential as SHORAD and EW.

Envisioning a New Force

The points outlined here are only a starting point for thinking about the future employment of armor of all types. The requirements for individual countries will vary greatly, but two points stand out:

Anti-drone and missile protection has to be disaggregated from armor

Maneuver units need considerable engineering assets

Given these demands, the RUSI paper was right to put great emphasis on logistical and sustainment requirements. AFVs will face stiff competition for resources on the move, anything that lightens or simplifies their burden increases their overall mobility—the outsourcing of protection to UAVs may even make possible the suggestion that tanks reduce their armor.

But above all, engineering assets will be what makes or breaks future offensives. The past year in Ukraine has shown how important they are against prepared defenses, but they will be just as essential for enabling operational maneuver—bulldozers and entrenchers may prove to be for 21st-century land warfare what artillery was in the early 20th.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

I suspect that the potential effectiveness of hard-kill anti-drone systems isn't being taken seriously enough. Having watched a lot of FPV drone footage, in most strikes there is a several second window where an automated, optically controlled shotgun type weapon or even grenade launcher firing upward could likely trigger a premature warhead demolition if onboard EW systems fail.

Disaggregating protection from targets is an interesting idea, and totally agree that dozer blades need to be standard on tanks. But my assessment is that tanks will need to be equipped with anti-drone systems and EW to create a small bubble for infantry to operate. Almost like a small naval task force, tanks, IFVs, and scout vehicles work in groups of 6-8 to control a 2km x 2km box with support from fires and air/EW defense. Whether attacking or defending they operate as a cell seeking to stalk, ambush, and annihilate any forces in their assigned area.

Need digital simulations to test out all the possible configurations.

Drill tanks digging tunnels underground.

Seismographs placed along defensive lines to detect them.

Artillery fired at or near said graphs to deafen them to drill tanks.

Soon (tm).