Relitigating the Past: Using Historical Case Studies to Understand the Future

Historical case studies are tremendously useful for understanding the principles of war, from the tactical to the grand strategic. They are somewhat less useful in a more immediate sense, for training modern practitioners how to fight the types of wars they are likely to face. Even subtle differences of equipment and organization can completely upend decision-making once bullets start to fly.

World War II is the earliest point at which case studies become legible in modern terms: the combined-arms trinity of infantry, artillery, and armor supported by airpower remains the basis for all modern tactics. But there are plenty of devils in the details, even accounting for the evolution of weaponry. Technologies that have long been taken for granted, like GPS, satellite recon, or the proliferation of light radios free commanders of constraints that their predecessors faced, while opening new operational avenues.

But what if we reimagine those case studies in a modern context? Historical examples provide an excellent framework for tactical decision-making; by examining how modern units would approach a well-known problem, we can gain a deeper understanding of how new technology alters familiar dynamics.

There are many ways to do this. The first is to take a scenario in isolation, updating the TO&E to reflect contemporary force structures, then play it out as a decision game, reasoning through how attackers and defenders would approach their tasks in a modern context. Take the Allied advance through Italy in World War II. This is fertile ground for case studies, involving many attacks on fortified positions in mountainous terrain under the cover of air superiority—an eminently plausible scenario for a modern war.

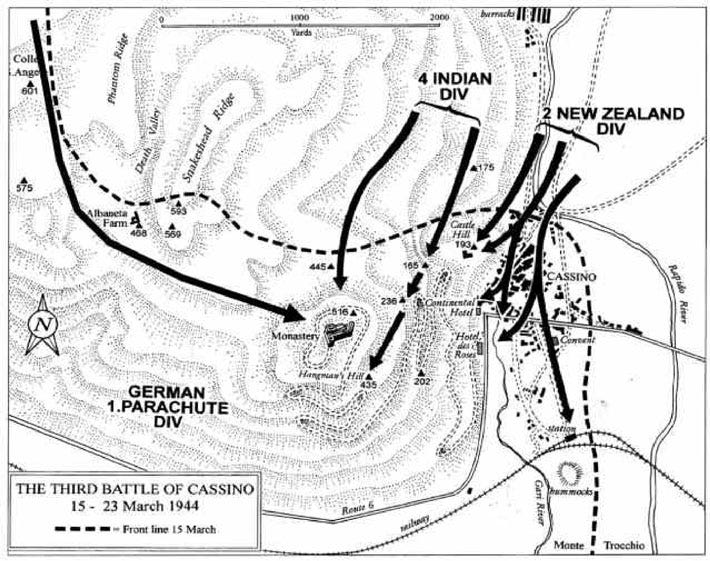

The Battle of Monte Cassino, in which the Germans held up the Allies for four months on the road to Rome, one such example. Much of the fighting was concentrated on the heights above Cassino, held by a single German division. Throwing modern weapons into the mix raises lots of questions that defy assumptions about both the defense and the current state of combat.

Would the defenders be able to sufficiently dig in on the bare and rocky slopes of the surrounding mountains? Or would drones give them enough visibility that they might sacrifice the high ground for more protected positions? On the other side, how would the commander concentrate his forces to begin the assault? What kind of fires preparation is needed before and during the assault?

Purely as tactical decision games, these scenarios are useful in their own right. But the use of historical examples serves another purpose: by comparing solutions with the actual outcome, students can develop an intuition for how new weapons disrupt familiar dynamics. Much of the tactical curriculum taught to young officers is formed around obsolete assumptions; at the other extreme, prognostications around new technologies are unhelpfully broad (“the future battlefield will be transparent!”). It is therefore a useful exercise to pick apart precisely how and why things change within a specific context.

This is particularly true as the rate of innovation accelerates. The appearance of new technologies at ever-shorter intervals means that the rules of thumb an officer picks up early in his career will quickly be superseded. Being able to anticipate the higher-order effects of new weapons is therefore an important skill to cultivate.

Higher-Order Effects

These sorts of questions naturally lead to another: what would it take for either side to prevail against an opponent with a given order of battle? To continue with the Monte Cassino example, how much infantry, artillery, and UAV support would be needed to reliably take the heights? And what about the tradeoffs among the three—if drones and fires can eliminate most of the defensive positions, are multiple infantry divisions even needed? What other specialized equipment is required for mission success?

This line of questioning can be extended to the broader concept of operations. If modern weaponry gives the attacker or defender such a great advantage, would their opponent even try to defend or assault the heights to begin with? Would it be easier for the Allies to fight through the lowlands and cut off the enemy from the rear? Or would the Germans, unable to hold the heights with a single division, use them to canalize Allied forces in then counterattack their rear?

In other words, how do changing tactics shape the operational level of war? As the 2023 Ukrainian counteroffensive showed, outdated tactical assumptions can doom even the most careful preparations—although higher levels of war are supposed to dictate actions to the lower, the lower-level reality still gets a veto. These sorts of misapprehensions are precisely why the Allied advance stalled so long at Monte Cassino in the first place. Even as late as 1944, the effects of new weapons and tactics in mountainous terrain still defied generals’ expectations, leading to repeated failed assaults. In the end, it was only by committing many more divisions to the attack in coordination with a much larger operation across a 30-km front that they managed to dislodge the defenders.

Nor must one stop at the operational level. Given the difficulties of campaigning in Italy, would an invasion in the present day even be worth it in the first place? If so, what should the objective be: to provide airbases to strike Germany, to tie down forces that might be sent to France, or to achieve an outright breakthrough? There is endless room to play with changing assumptions.

21st-Century History

World War II is the earliest that examples can easily be drawn from, but more recent case studies are also useful. Conflicts that are still fresh in living memory seem almost antiquated when examined in any detail, and would look surprisingly different if fought today. I tried to imagine just what an invasion of Baathist Iraq would look like in the present day, assuming a modernized and more competent opposing force. This was a very rough sketch that only examined the tactical and lower operational levels—a demonstration of the problems facing an invading force, not a serious operational study.

But there is no limit to this kind of intellectual tinkering. In a phenomenon as complex as war, it is only by playing around with the consequences of small changes that we can really understand the full range of the dynamics at play. And only by revisiting the assumptions of the last war can we realistically grapple with the next.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have access to occasional exclusive pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Funny, I just wrote a piece comparing a Ukrainian Mechanized Brigade and a WWII American infantry division

The Tactical Notebook publishes lots of exercises like this, as well as pieces about finding sources and running games. It also sponsors decision-forcing case studies conducted over Zoom.