Small Wars and Decisive Battles: Dien Bien Phu

Yet the Greeks are accustomed to wage wars, as I learn, and they do it most senselessly in their wrongheadedness and folly. When they have declared war against each other, they come down to the fairest and most level ground that they can find and fight there, so that the victors come off with great harm; of the vanquished I say not so much as a word, for they are utterly destroyed. Since they speak the same language, they should end their disputes by means of heralds or messengers, or by any way rather than fighting; if they must make war upon each other, they should each discover where they are in the strongest position and make the attempt there.

-Herodotus, 7.9

There is an old idea that Greek hoplite warfare emerged as a way to have it out between two sides, to end conflicts quickly with a clear winner and loser. War was expensive for subsistence agrarian societies, and the destruction of farmlands could make even victory a catastrophe. Hoplite combat, according to this view, was a sort of gentlemanly agreement to decide their differences with a fair and honorable fight so that all might return to their farms. Battles were often initiated by literal invitation, wherein one army would form up on one side of a plain and challenge the other to fight.

This view has fallen considerably out of fashion. Its critics point out that the victors often imposed brutal peace terms and were not above ruthlessly slaughtering a fleeing enemy—the stakes were maximal. More to the point, most warfare was not even waged by heavy infantry on open battlefields: the Greeks often used ambushes or set up defenses in rough terrain. The Athenians tried to avoid land warfare altogether during the Peloponnesian War, employing their naval superiority against Sparta and her allies.

Yet that does not account for the prominence of pitched hoplite battle. A weaker form of the classic view might suffice to explain the incentives. Horrible as the risks of open battle might be, the economic devastation from protracted war was far worse. A weaker army not protected by geographic features and without the option to spring ambushes might prefer to gamble on a pitched battle. If they were going to be subjugated anyway, they might as well go manfully to their fate without enduring a ruinous war, and the vagaries of ancient battle gave them an outside chance of pulling out an unexpected victory.

The Battle of Leuctra illustrates the complexity of motives that lead to a decisive clash. A Theban army tried to hold the passes into Boeotia against a much larger host of Sparta and her allies, but their adversaries made a roundabout entry into the plain. At this point, both sides resolved to give battle. Xenophon makes their calculations explicit. The Spartan general was under political pressure at home to attack the Thebans, while the Thebans’ very survival was at stake. If they allowed themselves to be besieged in their home city, the common people would turn against them and they would be exiled, losing everything; they therefore decided to settle the matter sooner rather than later. And as it turned out the Thebans did win, owing in part to innovative tactics that justified the gamble.

More often, both sides were convinced they could win a fair fight, so a decisive battle was a matter of finding a mutually acceptable battlefield. These considerations were not unique to the Greeks: armies of medieval and early modern Europe often engaged in extensive maneuvers trying to find suitable ground to challenge their enemy. Even in an age of continuous fronts, Soviet preparations at the Kursk salient were akin to an invitation to battle. What made the Greeks different was the stakes of this single encounter. A hoplite army constituted the majority of a city’s fighting strength, putting the outcome of the entire war into question.

Decisive Battle in Small Wars

This leads us to the central problem of small wars. Almost by definition,1 small wars reflect a power asymmetry that gives weaker parties every disincentive to commit their full strength to a single clash. Their path to victory lies either in gradually building up strength until it can contest the enemy on an even footing (Mao’s doctrine), or making occupation too exhausting or politically unpalatable to continue (a prolonged insurgency).

Meanwhile the stronger party is usually bound by political limitations, especially when it is an occupier, or simply lacks the resources to flush out rebel-held areas. Although it is possible in principle to win a small war by military means, this is not always easy. Sri Lanka’s 26-year civil war illustrates the difficulties: national forces eventually won by simply overrunning the Tamil Tiger’s territory and killing their leadership, but this only followed a long build-up in military strength and a difficult political process which got outside countries involved. A well-entrenched and politically adroit rebel army can often hold out indefinitely, building up their forces or awaiting a favorable turn in the climate.

Indochina

This gives us an interesting perspective on Dien Bien Phu, the culminating clash of the First Indochina War. It involved much more intense combat than had been seen in the conflict. Vo Nguyen Giap, the Viet Minh commander-in-chief, committed over half his total combat strength to the fight, making it as decisive a battle imaginable in a war that had seen only intermittent division-level actions. It might first be asked what prompted Giap to take such a risk.

From the start of the war in 1946, the Viet Minh adopted Mao’s concept of turning a guerrilla army into a regular one. They organized their fighters into battalions then larger units, training them to conduct larger-scale operations. By 1951, Giap had begun committing his forces to major assaults, launching a series of multi-division attacks on French bases around Hanoi. All were beaten back with heavy losses, prompting the Viet Minh to return to their strategy of attacking supply lines; they also began making inroads into Laos, which was harder for the French to defend from their coastal enclaves.

In 1953 a new general, Henri Navarre, took direction of French strategy. He planned a series of clear-and-hold operations in the northern lowlands to cut off Viet Minh sources of food and manpower, to be followed by a highlands campaign the following year. By this time, however, pressure was mounting on both sides to end the war. Stalin had died in March and the Korean War ended in July, motivating the major powers to seek an easing of tensions in Southeast Asia. Weakening domestic support in France was moreover driving the government to seek a politically-acceptable exit plan. The two sides agreed to hold talks in spring 1954.

Despite the push for peace, the end of hostilities in Korea freed up equipment on both sides to be used for one last effort. With talks looming, both sides had every incentive to win a major victory to increase their leverage at the negotiating table. The only question was where.

The Invitation to Battle

The Viet Minh decided to make their bid in the highlands, to expand their position in Laos and in the northwest, away from enemy centers of strength. The French position was more difficult. They required a resounding military victory, which ruled out any operation in the lowlands where guerrilla forces could simply disperse into the wider population. They had to offer battle in a way that was simultaneously a threat and an opportunity for Giap.

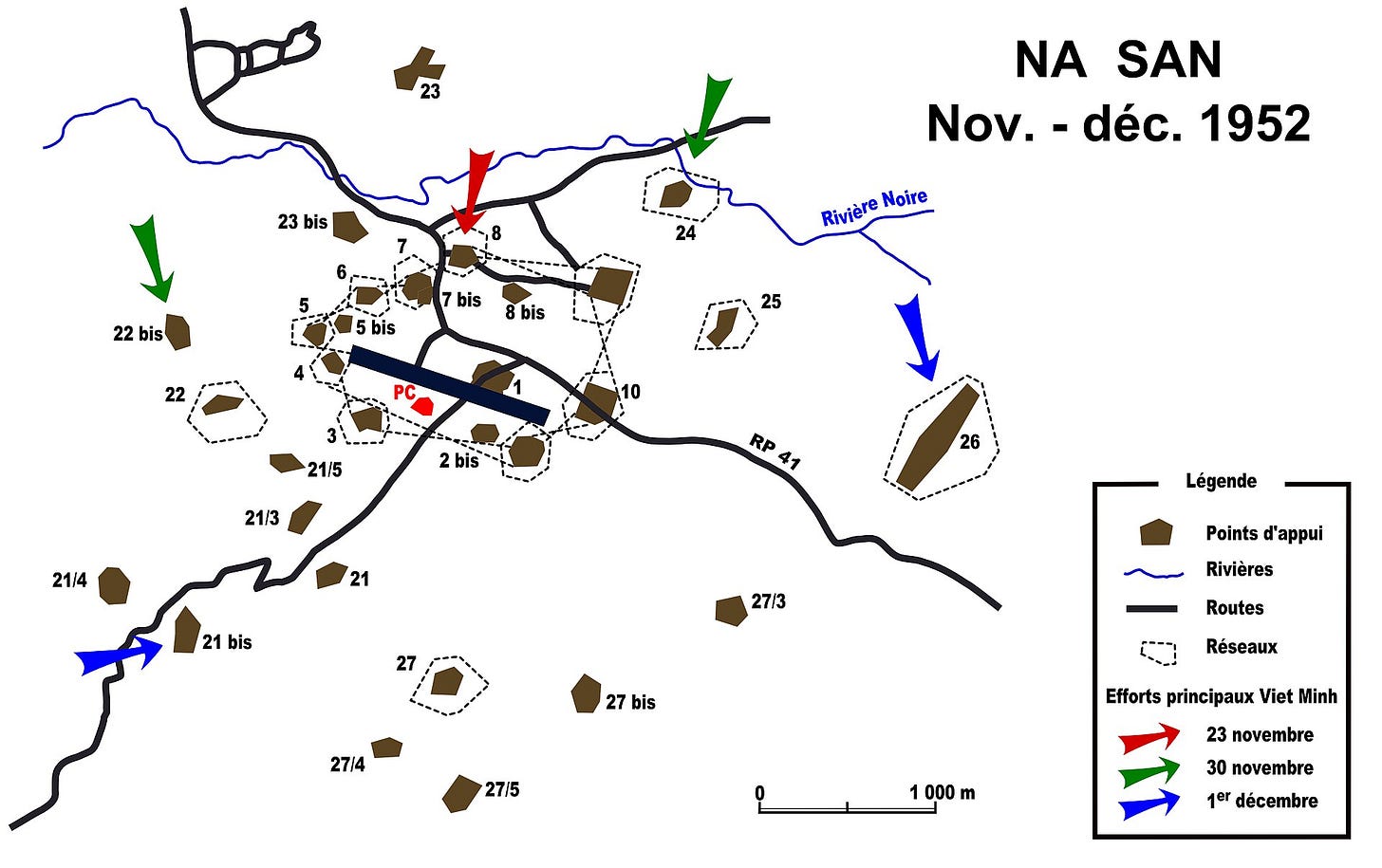

Dien Bien Phu offered both. Its remote location on Vietnam’s northwestern border posed a danger to Viet Minh supply lines into Laos, but made it easier for them to sustain an attack against it. Navarre also had reason to be confident in the location. In late 1952 Giap had launched yet another multi-division attack, this time on Na San, a base just 65 miles east of Dien Bien Phu. In a two-week battle, a much smaller French force held out against three Viet Minh divisions, inflicting heavy casualties. They were aided by two key factors: an airstrip that allowed resupply and reinforcement, and a network of strongpoints surrounding the main base. Both of these would be replicated on a larger scale at Dien Bien Phu.

In short, Navarre had found a suitable field to offer battle. The French occupied the area in strength in November 1953, and at the beginning of January the Vietnamese Politburo approved a major offensive against the fortress. Both sides spent the next few months building up their strength and constructing fighting positions. The French pushed 12,000 troops into the base, to be reinforced during the fighting, while the Viet Minh committed more than 50,000—over half their entire fighting strength. On 13 March, less than two months before the opening of peace talks in Geneva, Giap launched the assault.

Reaching Decision

The two-month Battle of Dien Bien Phu bore every hallmark of a decisive battle. Neither side had a complete picture of the other’s strengths and weaknesses going in, but both foresaw a reasonable chance at victory. In the end this favored the Viet Minh, who had received much more and better equipment than the French anticipated, negating their airpower advantage. Much of the outcome also came down to decisions made during the battle: the Viet Minh proved tactically flexible, Navarre committed forces elsewhere that could have been used to reinforce the outpost, and the Americans refused direct air support. Finally, the outcome brought a decisive end to the war. At the Geneva Conference, Paris was moved to allow Indochina’s independence and the partition of Vietnam, leaving the Viet Minh in control of the North.

It was a unique combination of political factors that allowed a decisive battle to be fought in the first place. Both sides faced pressure to end the war, a factor not usually present in small wars. French objectives were a politically-favorable exit from Indochina, not indefinite control. And in order to bring about such a battle, the French had to willingly run a high risk of defeat against a weaker foe. Nevertheless, it is a striking example of how a small war could be decided by the same logic that drove hoplites to form up on the plains of Leuctra.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

I define small wars as those in which combat can be conducted at the upper tactical or at most operational level. That is to say, strategic objectives cannot be accomplished be either side through military means alone. This usually arises from an asymmetry in strength, but not always: two powers commit too few forces to a theater to achieve any kind of decision, which in any case presupposes a larger conflict.

Dien Bien Phu once again proves you want ground artillery and not primarily air artillery, a lesson we the West and America can’t learn.

That’s not saying “no air, no CAS” it’s you must have ground artillery superiority or at least parity and not rely on air support, never mind air supply. Cannons aren’t sexy but they work in any weather. Mortars aren’t high tech but in the Army now it’s the first question we salts ask “you’re taking the mortars, right?”

The USMC are about to learn this lesson about organic artillery and armor again, and no “high tech rockets” aren’t the same. In WW2 there were early assaults in the Pacific and by the Army as well where they didn’t take enough artillery, cuz like Air. Costly.