The Chain of Combat, Part 1

Classifying War

America’s two-decade involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq ranks as one of the most substantial commitments of military power outside its traditional role. An organization designed to fight major wars against peer competitors found itself engaged in a protracted police action, oriented around the prerogatives of counterinsurgency.

It is somewhat jarring, in retrospect, how readily the label “war” was attached to these conflicts. Certainly, there was occasional high-intensity fighting, some of which employed the full spectrum of military force. But the battlefield was explicitly not where victory was to be won: that was to be at polling centers and government councils. It is all the stranger, then, how these conflicts were dressed up in the ordinary vocabulary of military doctrine: counterinsurgency campaigns targeting the enemy’s center of gravity—the support of the people—were to be waged with the help of influence operations.

At the time, this seemed perfectly natural. There was lots of discussion about how warfare was changing, how wars in the future could take all kinds of forms—the military had to be ready to adapt. Some, such as advocates of the fourth-generation warfare model, went so far as to argue that the world was on the cusp of a phase transition in the nature of war itself.

Yet the prospect of conventional war loomed in the background. The growth of Chinese power and tensions with Russia revived American concerns over interstate conflict. Talk of COIN and asymmetric warfare began to dwindle long before the final US withdrawal from Afghanistan, as debates shifted back to weapons systems and high-tempo operational doctrine. With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, counterinsurgency became a distant memory.

None of this, however, has prompted a real reckoning with the manifest failures of COIN. The failure of US efforts is admitted easily enough, but counterinsurgency doctrine itself has not been put to any thorough reexamination. In the meantime, the shift of focus to “great power competition” has generated a new body of unofficial doctrine around “hybrid” or “gray-zone” warfare. Again, the glib use of the word “war” should concern us: it allows us to entertain the use of military force without really considering its purpose or effectiveness.

What Is War?

Rather than mire ourselves in a semantic debate about what constitutes a real war, let’s look at how we classify wars. There are several ways to do this: by intensity (from border skirmishes to total war), symmetry (insurgency vs. interstate conflict), style of combat (maneuver vs. attrition), and so forth.

Instead, let’s use what I call the chain of combat. This is the entire sequence of kinetic actions that precipitate the defeat of an adversary, extending from the smallest firefight to the largest theater maneuvers. The chain of combat runs parallel to the chain of command: an artillery battalion supports a brigade attack, which supports a divisional penetration, leading to a corps envelopment, etc.

The chain also extends through time, as one combat operation usually sets conditions for the next: from the opening bombardment to the myriad combats throughout to mopping-up operations after organized resistance has been broken, interrupted only by the time it takes to rest, refit, and plan the next phase.

This, at least, describes most major wars of the past few centuries: the Napoleonic Wars, the American Civil War, the Wars of German Unification, both World Wars, and the envisioned NATO-Soviet war in central Europe. Most modern doctrine was written for exactly this kind of war, in which both sides try to break the other’s ability to put up organized resistance. Success demands the traditional operational virtues such as speed, surprise, and overwhelming force on the objective, maintained at tempo until the enemy capitulates.

Such conflicts, in which the chain of combat runs uninterruptedly from individual soldiers up to the highest theater command, can be called full-scale wars. This should not be taken to indicate the length or intensity of a war: it describes the long and destructive World Wars just as well as the seven weeks of Desert Storm—or, for that matter, the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Which brings us back to our initial question: what makes the occupation which followed Saddam Hussein’s overthrow fundamentally different from the drive to Baghdad? Superficially, the war never ended. Sporadic fighting soon turned into a full-blown organized insurgency, answered by ongoing Coalition combat operations.

But the mission had ceased to focus on the military defeat of the adversary. A battalion might be tasked with pacifying specific armed groups in its AO, while its parent brigade’s mission was to set conditions for peaceful elections. Combat was mostly limited to small and disconnected ambushes and raids—with the exception of major clear-and-hold operations, engagements rarely exceeded company size. Both sides struck when they had the means and the opportunity, not to immediately exploit success—at most, a raid might yield intelligence which had to be acted on quickly to bag an insurgent leader. The same was true from the insurgent’s perspective: a successful attack was followed by disengagement, not exploitation, because it inevitably prompted an overwhelming reaction from the much stronger adversary. There was a break in the chain of combat, in other words.

Asymmetric conflicts in which the chain of combat is broken at the low tactical level can be called pure insurgencies. The purpose of all organized violence is ultimately political, but in an insurgency it is immediately so. Ambushing patrols is meant to alienate the occupier from the local population; raids on bomb-makers are intended to build confidence in local political allies. These tactics serve no higher military purpose: it would be ridiculous to speak of operational maneuver in an insurgency, for instance (although many have tried). Moreover, military force is far from the only—or even the primary—tool in achieving long-term objectives: diplomacy, economic aid, and the media are usually far more important.

Small Wars

In between the sporadic fighting of a pure insurgency and the coherent operations of full-scale war is a broad range of conflicts often referred to as small wars. This covers many different types of conflict, including larger-sized insurgencies, minor colonial wars, and intermittent warfare between neighboring states. Although these are very different from one another, their common element is how the chain of combat is broken at the higher tactical or operational level.

Larger-scale insurgencies

We see this in larger insurgencies, where fighters are organized into brigade- and division-sized units which can occasionally unite to mount major operations. This is only possible when the insurgents control base areas where they can operate with relative freedom, in which the government or occupying force can only maneuver with difficulty. This is similar, but not identical, to the second of Mao’s three-phase model of revolutionary warfare1 (the first resembles a pure insurgency, while the third aims to fight a full-scale war).

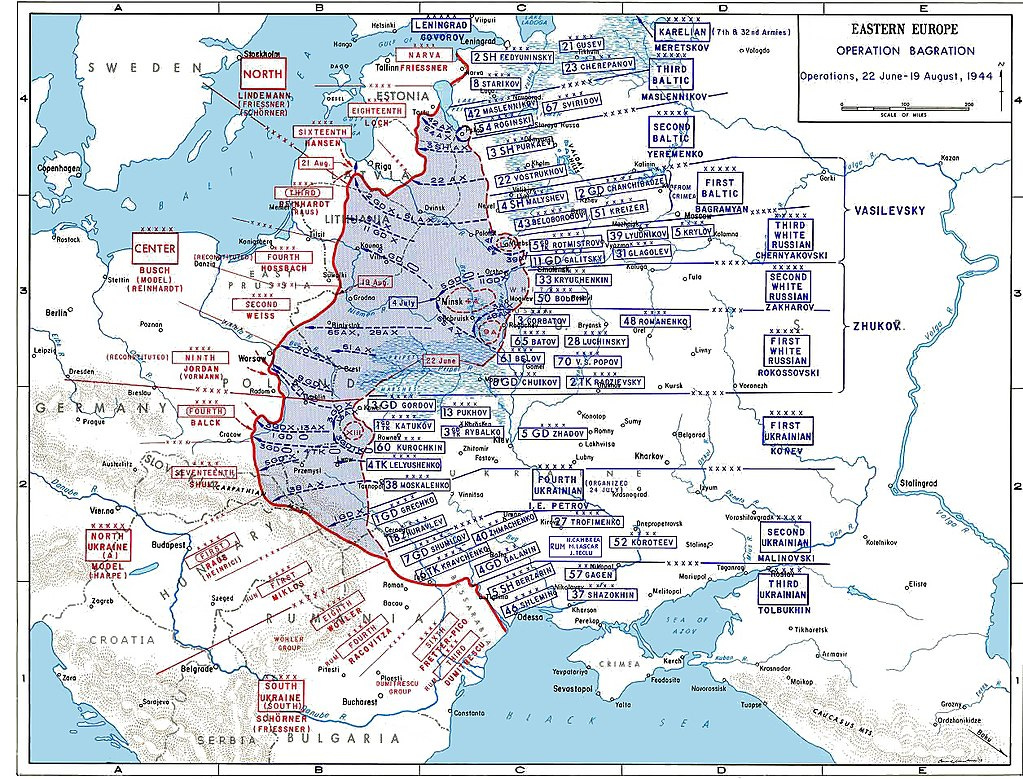

The most familiar example in American experience is the Vietnam War. Regular NVA formations fought alongside the Vietcong as a basically insurgent force, lacking the strength to sustain continuous operations against their enemies. North Vietnamese forces had protected basing areas in North Vietnam itself (off-limits to US ground forces for political reasons) and in the interior along the Ho Chi Minh trail. Fighting consisted of many large tactical engagements and US operational-level offensives.

The fighting occasionally blurred the lines between insurgency and conventional war, specifically during the 1968 Tet Offensive, which entailed simultaneous thrusts all across South Vietnam. But even this apparently strategic-level offensive with multiple operational-level axes of advance envisioned no higher military objective: its purpose was to delegitimize the South Vietnamese government and trigger uprising, not to destroy enemy forces outright.2 Only when US drawdowns brought North and South closer to parity could the NVA launch the Easter Offensive of 1972 with the aim of capturing Saigon—by that point, the conflict had transformed into a true full-scale war.

Another example of the shifting dynamics of insurgent small wars is Sri Lanka’s decades-long war civil war. The Tamil Tigers large parts of the country’s north and east, giving them freedom of action to launch a months-long campaign in 2000 to isolate and capture important strongpoints, which they managed to hold against subsequent assaults by the Sri Lankan Army. Government forces steadily increased their strength in the following years, however, and when fighting resumed in 2006 they were able to occupy all rebel-held territory, killing or capturing the Tigers’ leaders within a few years.

This shows a characteristic feature of large-scale insurgencies: they can be ended with military means simply by eliminating the leadership, even if political factors often preclude this. For the insurgents to win, on the other hand, they must transform into a regular army which can triumph on the battlefield—Mao’s formula for revolutionary movements, in other words. For all that these conflicts are similar to smaller-scale insurgencies in some ways, military force is the primary, if not the only, instrument of victory.

Colonial Wars

Organized insurgencies are the most common type of small war today, but historically there have been others. Colonial wars that fell short of outright conquest—what we might call gunboat diplomacy—share many of the same qualities.

The US occupation of Veracruz during the Mexican Revolution illustrates this. In 1914, a US Navy flotilla was dispatched to the Mexican seaport, where it blockaded the harbor and sent landing parties to capture the city. The aim of the seven-month occupation was neither to aid in the military defeat of Mexico nor to set conditions for follow-on operations, but to intercept arms shipments and put economic pressure on the government of Victoriano Huerta. Military intervention was only one tool along with diplomatic pressure, trade policy, and support to rebels, and of these it was probably the least important.

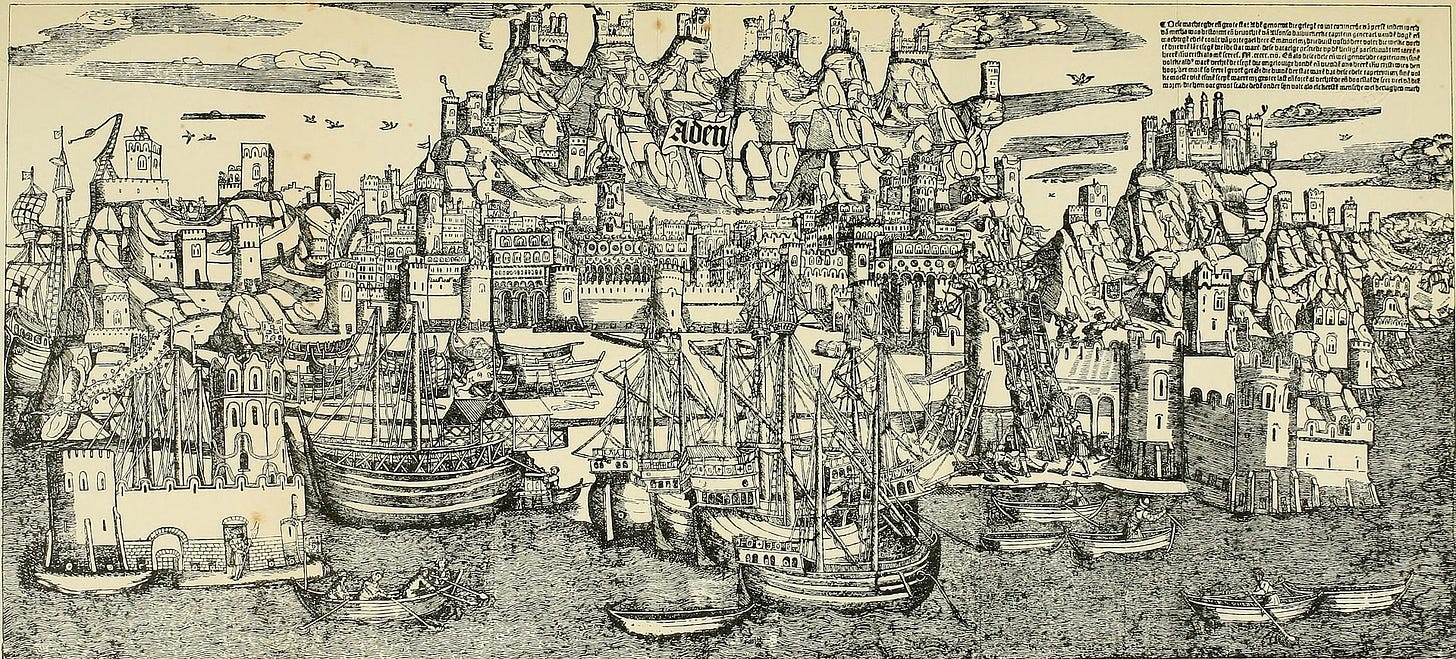

Small wars of this type were natural tools of colonial powers. Europeans during the Age of Exploration often outmatched their vassals and clients in overall strength, but they could not be everywhere at once. Punitive expeditions and occupation of port cities were far more economical uses of force than the outright conquests of the nineteenth century, and were easily augmented by commercial and diplomatic pressure: this struck directly at their client’s interests and left little room for a widening of the war.

Frontier Wars

Not all small wars demand a fundamental asymmetry in strength. It was common for endemic states of warfare to exist between premodern states, either in the form of seasonal raiding or episodic larger incursions. This is nowhere more clearly illustrated than on the frontier between Byzantium and the Arab Caliphate, where the two sides regularly clashed for over three centuries. There were several full-scale wars during this time, but most combat consisted of large-scale raids and limited incursions.

Warfare of this type aimed more for temporary economic gain than any permanent advantage. Seasonal fighting or multiyear periods of war were most often ended by treaty and the payment of tribute than any shift in the balance of power. It was rare for incursions to accomplish any true strategic objective, although they might well capture an operational objective, such as a key border fortress, which could prove useful in subsequent years. Seasonal wars were liable to escalate into full-scale war when one side assembled larger-than-usual forces and set their sights on more ambitious objectives, at which the defenders mobilized their entire military strength. This always required a conscious political decision, however.

To What End the Chain of Combat?

None of these categorizations should be too controversial. They might vary slightly from others’ definitions, but the only real difference is in framing. To what purpose the chain of combat, then?

Defining conflicts in terms of their ways and means makes it easier to understand hard-fought lessons from the past, in particular the reasons for failure. Coalition forces in Iraq and Afghanistan fought pure insurgencies more like small wars, with major operations intended to have decisive effects. In Vietnam, the US was caught between two paradigms, trying to fight a full-scale war in a limited theater. Success would have required either escalating to a true full-scale war (invading North Vietnam) or fighting as a proper small war. Against these examples, North Vietnam and the Taliban succeeded because they only attempted operations higher up the chain of combat when they had reached parity with their enemies.

In Part 2, we will look more at what this tells us about how wars are won and lost.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Marxist-Leninists classified wars according to their socio-economic purpose: imperialist, national liberation, and revolutionary.

Even so, the North Vietnamese leadership was wildly optimistic in their estimates of the South Vietnamese reaction. The real success of the offensive—delegitimizing the war with the American public—was entirely unintended.

Nice article. I think you should read Clausewitz’ book and see where he dovetails with your argument. Distilling him down to basics though is “war” is use of force to compel your enemy to do your will. He also lays out the spectrum from wars of limited aims and goals to unlimited war at the top end designed to completely (and he meant completely) destroy the enemy. The closest we ever probably got was WWII in the Pacific Theater if the Japanese didn’t capitulate after the atomic bombings.