The Rappahannock Line: Mobile Warfare Along a Frozen Front

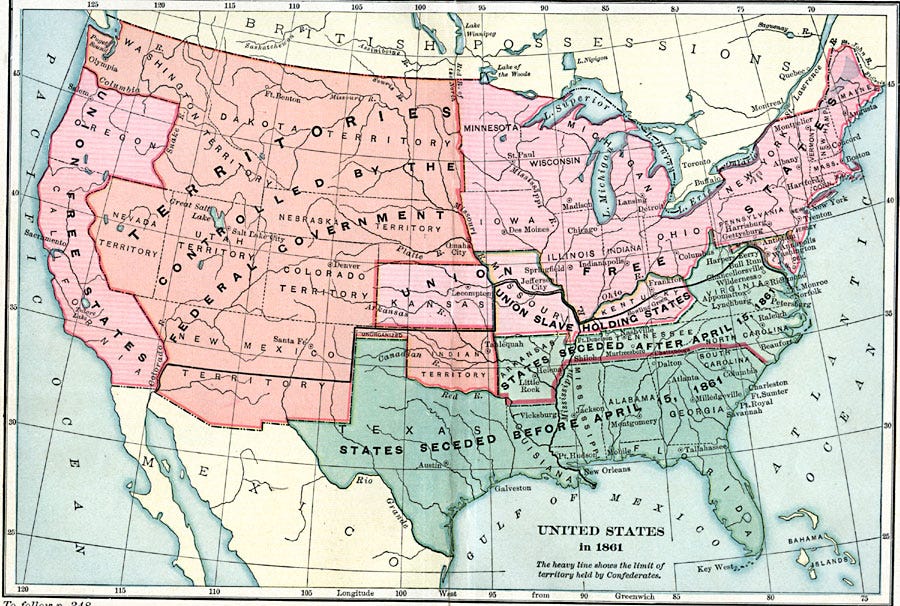

For the first three years of the American Civil War, the Rappahannock River was the effective boundary between North and South. Even as the war sprawled halfway across the North American continent, the attention of most observers remained focused on northern Virginia. This was the crucial theater, the contested ground between Washington, DC and Richmond, where the war was most likely to be decided. As such, operational considerations in this sector took on an outsized importance, shaping both sides’ strategies. And of these, the greatest was the Rappahannock: a modest river of some 300 kilometers in length.

A previous piece looked at how the French army of the early 18th century defended a comparably wide front through the use of fortresses, water obstacles, and entrenchments tens of kilometers long. Although nowhere near numerous enough to defend the entire line, local detachments could usually fend off an incursion long enough for the rest of the army to show up in strength. In this way, the army-in-being was able to defend an extended linear front which shifted but slowly as the attacking army painstakingly reduced one obstacle after another.

The influence of the Rappahannock was far more indirect. Most of the fighting took place well to its north, while Union forces made occasional forays to the south. Unlike northern France, northern Virginia had never been a frontier zone and lacked the same thicket of fortifications that had been built up over many centuries. This gave warfare a more fluid character: an adroit maneuver could get into the enemy’s depth, but would not necessarily advance the positional fight. This affected operational considerations throughout the whole of northern Virginia, shaping how both sides conducted offensive and defensive campaigns. And most notably, it resulted in a very mobile style of warfare that hovered around fixed lines.

The Eastern Theater

The American Civil War lasted a brutal four years, but even by late 1862 the cost was not obvious. The bloodiest campaigns lay ahead, and only a few actions—Antietam or Shiloh, for instance—reached the casualty tolls that characterized its last two years. Abraham Lincoln still saw his best chance at victory in the Eastern Theater, where he hoped to knock out the Confederacy with a few sharp blows. In particular, his focus was on the Army of Northern Virginia. Southern territory was vast, giving them plenty of room to withdraw even if Richmond was taken: only by destroying Lee’s army away from Richmond could he hope to bring the breakaway states back into the Union.

Confederate strategy, by comparison, was less clear-cut. There was no obvious way to defeat the North outright, so their immediate priorities were overwhelmingly defensive. Although Lincoln was probably correct that the early fall of Richmond would not end the war, it nevertheless would have been a heavy setback, making its defense a major objective. Both sides, therefore, had reason to concentrate their efforts on the Eastern Theater.

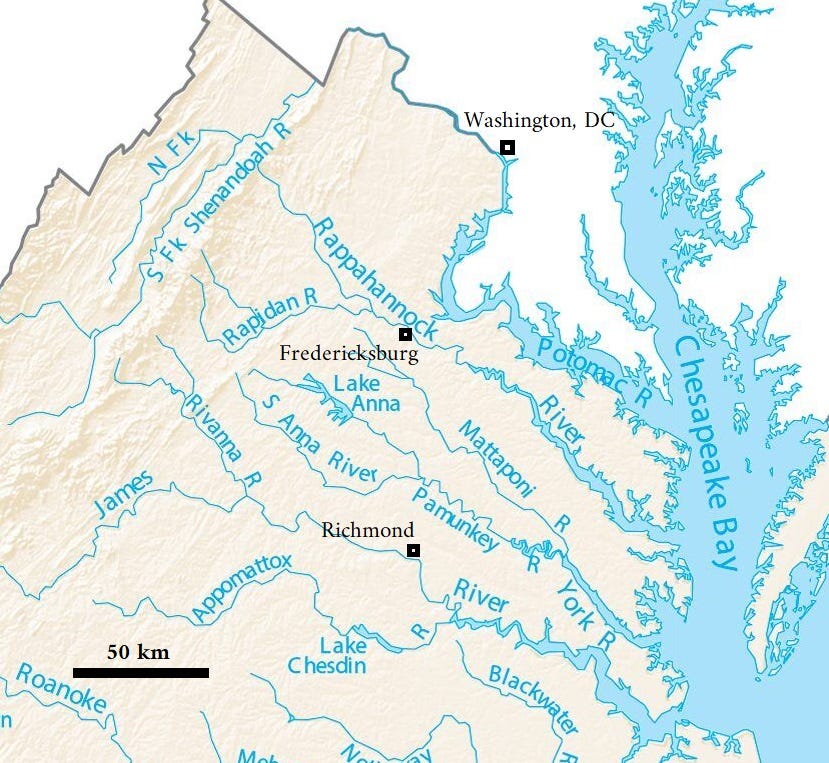

Northern Virginia is cut through by many rivers, which flow southeast from the Blue Ridge Mountains into the Chesapeake Bay. The two biggest of these are the Potomac, which forms the state’s northern border, and the James, which flows past Richmond. The Rappahannock lies halfway between these two. Not an especially large river on its upper course, it begins to widen about 15 km above Fredericksburg, where it is joined by a right-bank tributary, the Rapidan. The hilly country around the upper Rappahannock, combined with the secondary obstacle of the Rapidan, made this section difficult to traverse, while the river’s wider lower course had relatively few fords or bridges.

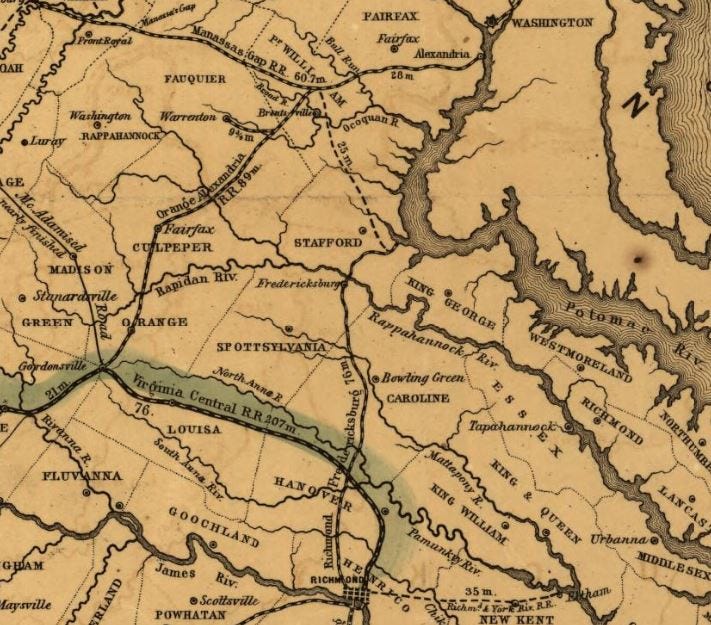

These difficulties were exacerbated by logistical questions. Whereas armies could range pretty freely along the front, they could not move far past their supply depots. The major rivers ran perpendicular to the direction of Union advance, ruling out their use as a supply artery, which left the Army of the Potomac constricted to two rail lines. The major north-south line was the Orange & Alexandria, which ran from the Potomac near Washington to a terminus at Gordonsville; from there, it linked up with the Central Virginia Line, which ran less than 100 km southeast to Richmond. This ran through open country with no major obstacles, where the Union could put its greater numbers to good use, but the single-track O&A line could not support large armies.

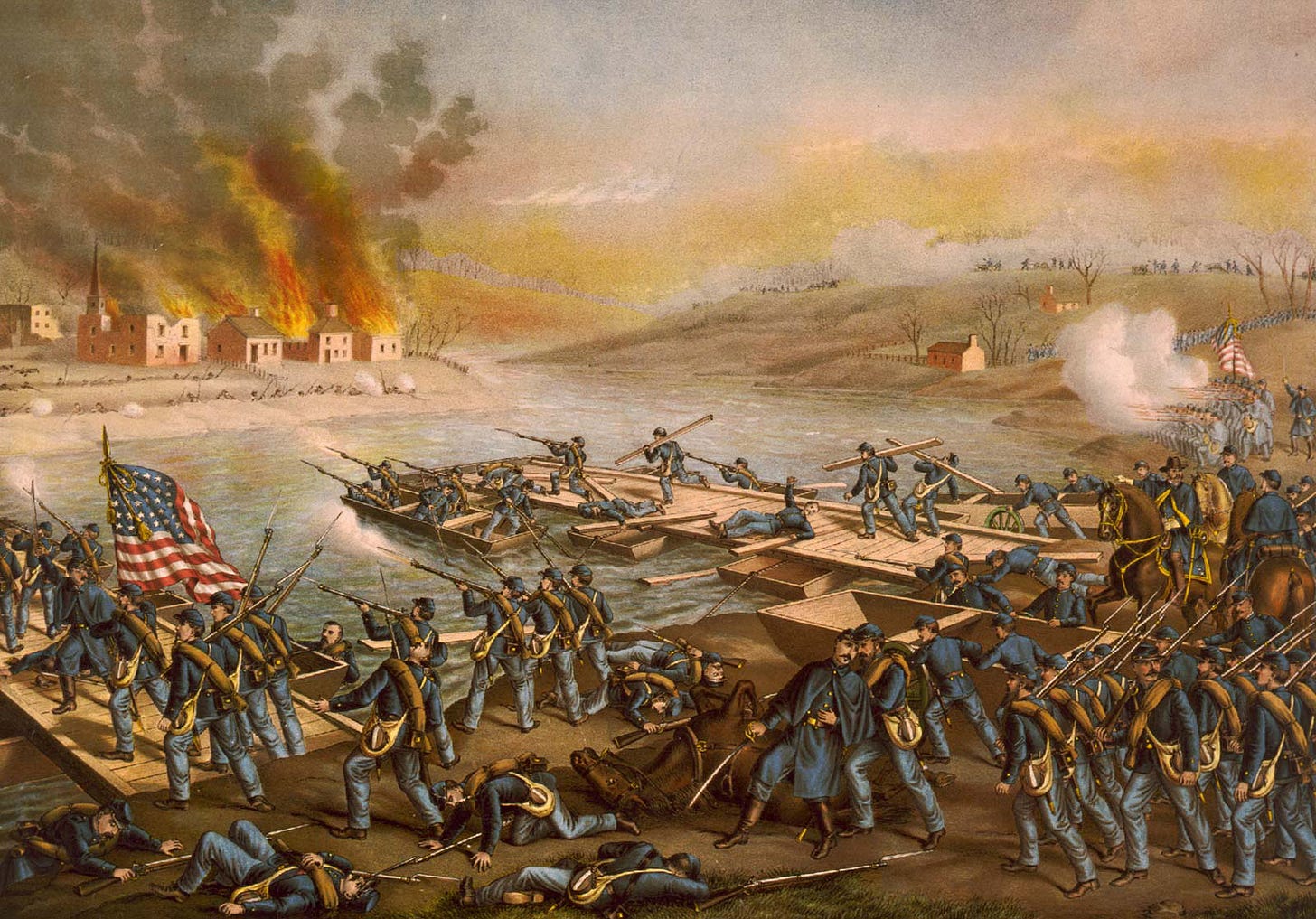

The Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Potomac Railroad had greater capacity. This spanned the short distance between the lower Potomac’s southwestern leg and the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg, whence it ran south to Richmond. On paper this was an ideal invasion route—a railhead easily supplied by river—but things were not so easy. The Rappahannock was much wider at Fredericksburg than further upstream, meaning it had to be bridged, and an attack there could be easily anticipated.

The Peninsula Campaign

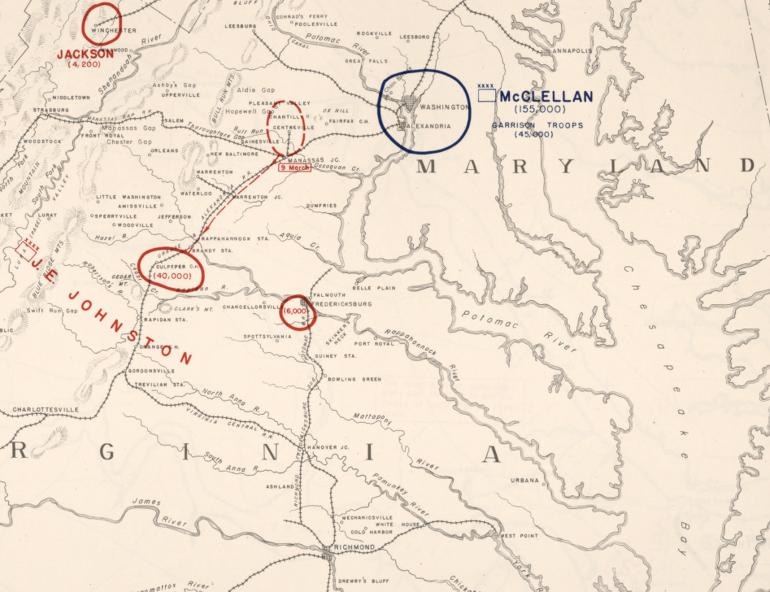

It was not until 1862 that this even came into question. Confederate victories in the first year in the war left them in control of the northern counties, almost to the Potomac itself. Joe Johnston’s Army of Northern Virginia posted itself at Centreville, just 30 km west of Washington, where it began digging in. This aggressive posture unnerved the risk-averse George McClellan, who in July was appointed the Union’s theater commander. He avoided any offensive action for the rest of the year, spending the autumn and winter building up the Army of the Potomac.

Yet as spring approached in 1862, McClellan resisted Lincoln’s urgings to march overland against the Confederates. He pointed out the operational difficulties posed by the Occoquan, a much narrower river than the Rappahannock, which would have to be crossed to get around the Confederates’ right flank—and the alternative of a long, exposed march around their left or an attack on their center were even worse. Instead, he proposed a seaborne offensive that circumvented this obstacle entirely: a flotilla would land on the right bank of the lower Rappahannock and march thence on Richmond.

Even on practical grounds, McClellan’s objections to Lincoln’s urgings were nonsense. Johnston’s numbers were far fewer and in a much less defensible position than his Union counterpart estimated. Moreover, his supply lines were stretched and he lacked the logistical apparatus to execute a quick withdrawal. Fearing a major Union offensive that spring, Johnston withdrew in March to the Rappahannock, the closest defensible obstacle. To Confederate eyes, at least, the river was their natural military frontier.

This threw a wrench in McClellan’s plans. Johnston was now in a position to contest his landing, so the Union general revised his objective. He shifted his landing point south to the Virginia Peninsula, to Richmond’s southeast. The plan had several merits to recommend it. The expedition could be supplied entirely by water, and a quick strike could take the Confederates by surprise. Lincoln reluctantly agreed to the plan, and the Army of the Potomac landed at the tip of the peninsula in late March.

McClellan was slow to advance, however, and after some promising early successes the Confederates were able to reposition their forces and contain his advance along the narrow approaches to Richmond. McClellan’s army was eventually forced to withdraw down the peninsula and reembark in their ships back to northern Virginia.

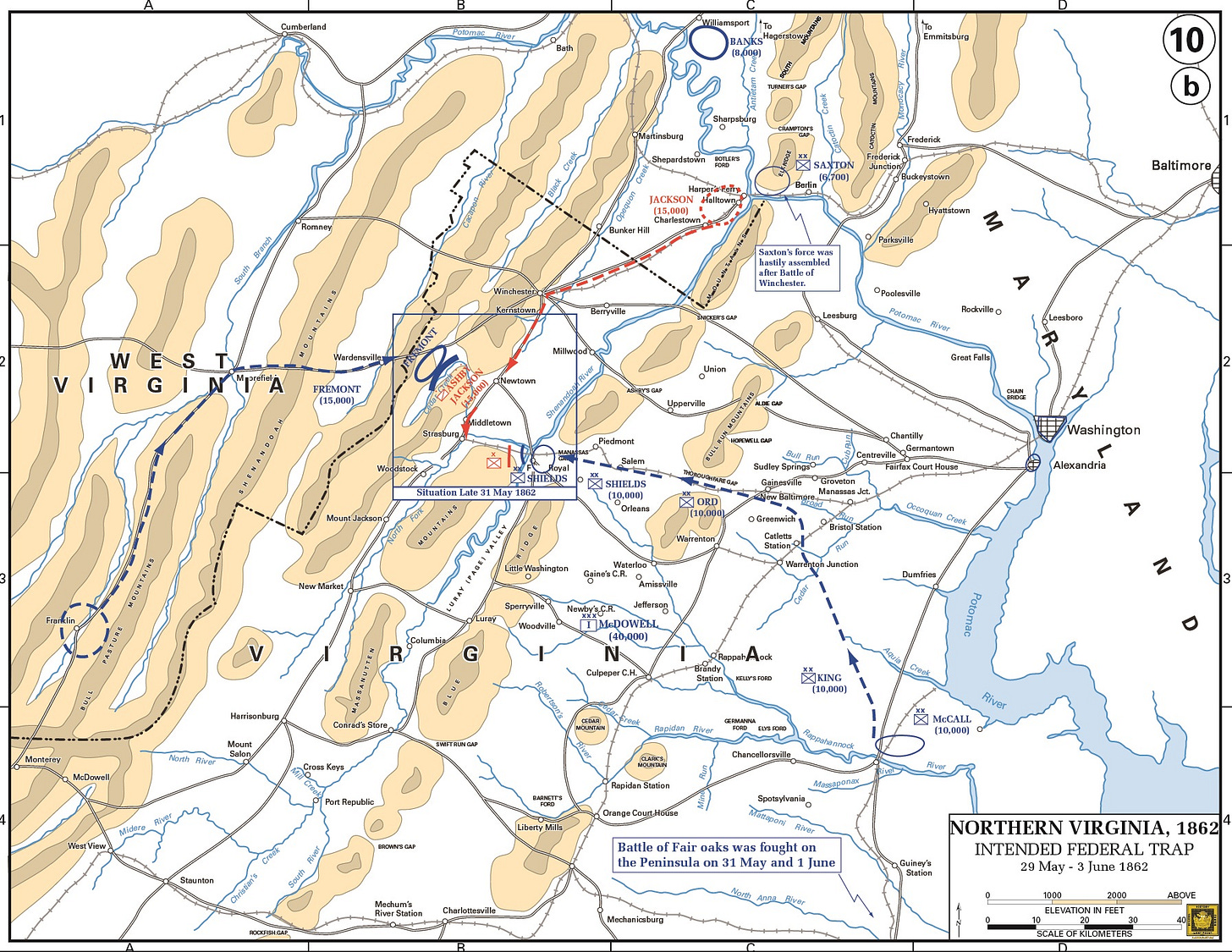

The operation did give Union forces the chance to pass forces over the Rappahannock, but this opportunity was also squandered. A large corps occupied Fredericksburg, and was tasked to proceed down the RF&P line to hit the Confederate flank. In the meantime, however, Stonewall Jackson had been active in the Shenandoah Valley and was tying down large numbers of Northern forces there. Even though Jackson was greatly outnumbered, Lincoln feared a move on Washington and diverted two divisions from Fredericksburg to the Valley, leaving the rest of the corps unable to do anything before McClellan’s withdrawal.

The failure of the Peninsula Campaign owed to many factors, but above all to a lack of boldness by military and political leadership. Although the plan was sound in principle, McClellan sacrificed the initiative which his bold landing had won, and Lincoln compounded the error by reassigning much-needed supporting forces to a chimerical pursuit. It should be noted in any case that success would have required careful synchronization over a large area—hardly less complex than a river-crossing operation would be.

The Northern Virginia Campaign

This failure nevertheless gave the Union the chance to cross the Rappahannock directly. In June 1862, Jackson marched out of the Valley to support Lee’s defense of Richmond, leaving no forces to speak of along the river’s upper reaches. Even before the Peninsula Campaign concluded, Lincoln constituted Union forces around the Valley into the Army of Virginia under John Pope. Its immediate task was to lift pressure on McClellan by crossing the Rappahannock in strength, then occupy the rail junction at Gordonsville to open the route to Richmond.

Pope arrayed his forces between the Rappahannock and Rapidan, but operations did not get underway until early August. By that time, McClellan had been defeated and Jackson was able to occupy Gordonsville. The Confederate general attacked and defeated Pope’s vanguard before the Union army could concentrate, driving them back toward the Rappahannock while buying Lee time to arrive in strength. Pope was also receiving reinforcements from McClellan, but these could not arrive as quickly, and he withdrew behind the river—making it a Union defensive line.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Bazaar of War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.