Units Built for Purpose: Structure vs. Adaptability

A recent piece from the Modern War Institute looks at the problem of creating and sustaining breakthroughs on the modern battlefield. Identifying four tasks that an attacker must fulfill in order to defeat a well-organized defense—breakthrough, exploitation, consolidation, and sustainment—the author notes the difficulty of achieving this in the face of a contemporary defense. Russia failed to achieve the last three steps during the 2022 invasion, while Ukraine could not manage even manage the first in the 2023 counteroffensive.

Among many reasons for these failures, the piece highlights the lack of coordination at the division and corps levels in these operations. To that end, it proposes the creation of four types of division in the US Army, each organized around a specific function: a recon-strike division to create the initial penetration, an assault division to exploit it, a consolidation division to secure the gains, and a sustainment division to ensure continuity of operations.

Although the piece makes an interesting argument for how operations should be sequenced to achieve effects at tempo, I believe the focus on designing units around function instead of capability also reflects a misguided trend in Western defense circles. This is seen in many proposals for restructuring the US and European militaries, and is already seen in the USMC’s Marine Littoral Regiments.

The attraction is clear enough. Purpose-built units give higher-level commanders off-the-shelf tools to accomplish specific tasks, while giving individual units the opportunity to study the operational problem and gain experience training as a whole. However, there are many even greater downsides. Their design embeds a lot of assumptions that cannot be validated, creating the risk trapping units in dead ends as technology continues to advance at a rapid clip and new needs arise. The MWI piece on breakthrough units, as a clear articulation of a common perspective, presents a good occasion to examine the broader problem.

Breaking the Line

Assuming that a modern ground force can indeed break through a near-peer’s defensive lines without wholly relying on airpower, two difficult questions arise: the scale at which breakthroughs can be accomplished and the balance of forces for each effort. Both are highly variable.

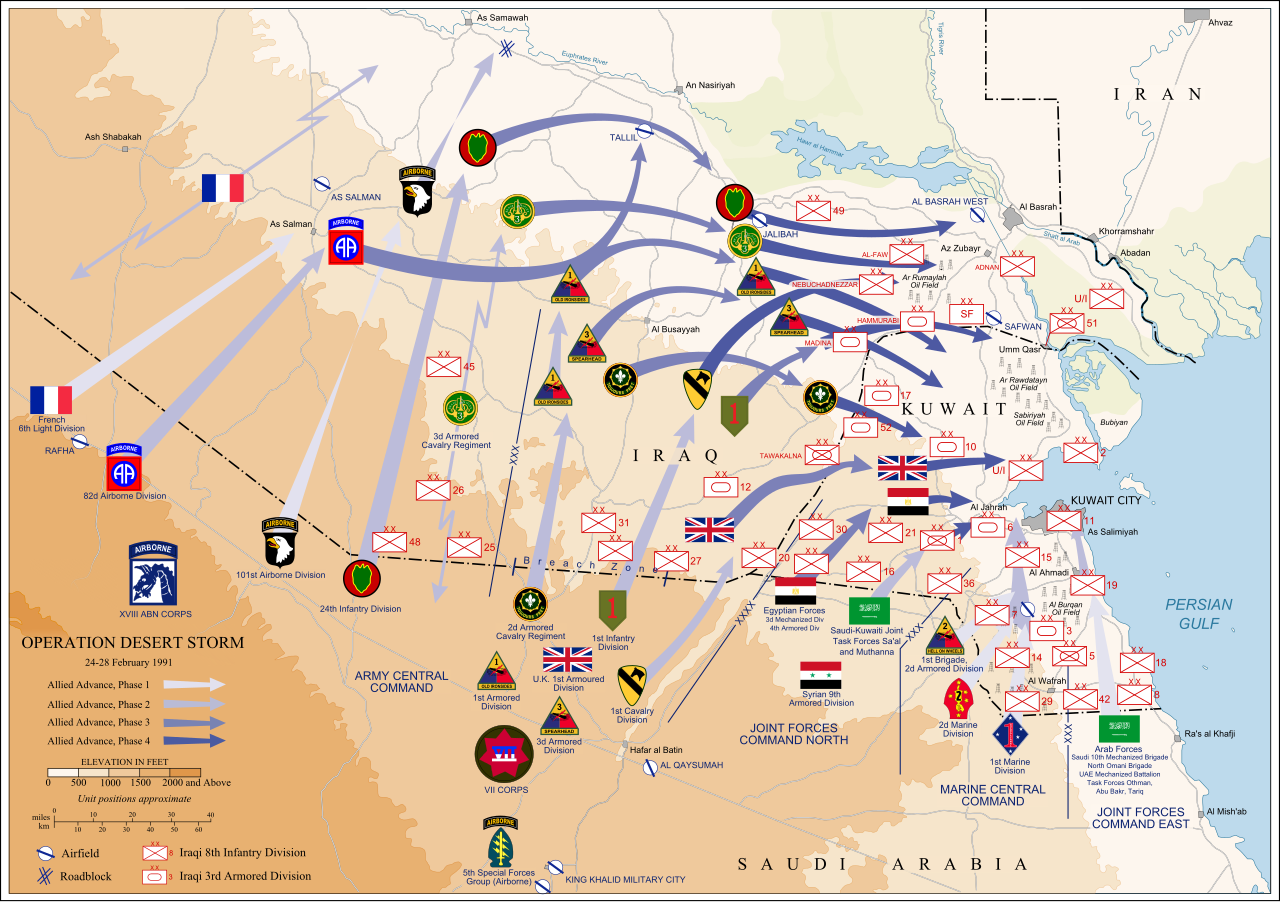

Tailoring individual divisions to the phases of a breakthrough reduces such an operation to a corps function, to be accomplished either by individually or online with other corps. This is very much akin to the ground campaign in Desert Storm, when VII Corps penetrated Iraqi lines and enveloped enemy forces facing the three corps on its right.

Yet that is just one example. In the second Iraq War, two much smaller corps advanced in parallel through the country, breaking through Iraqi defenses at the division level or below. In 1944, three entire army groups swept across Europe. While the latter involved many corps-sized breakthroughs, it also required the same at other echelons. Optimization at one scale does not necessarily translate to others.

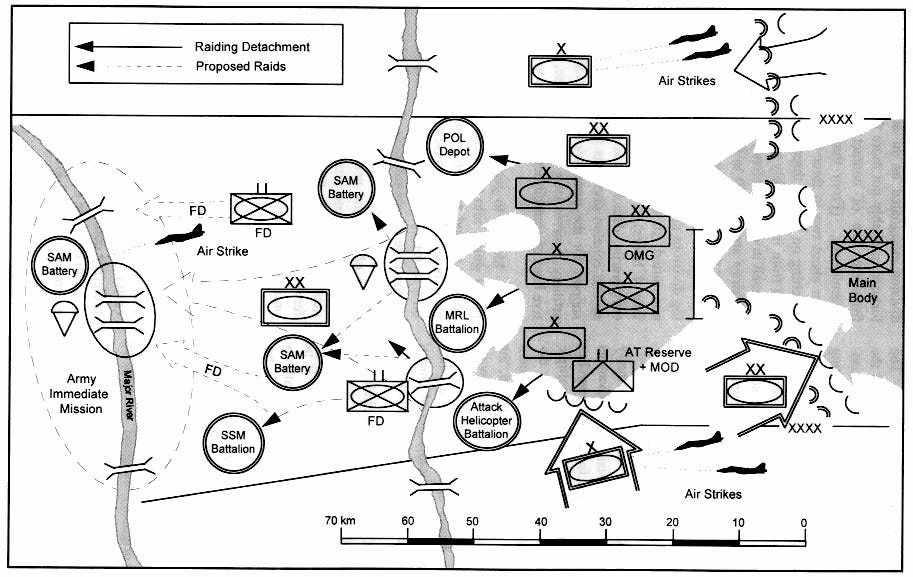

But let us suppose that these objections can be answered. A second difficulty is gauging the proportion of combat power necessary for each phase. This was a problem that vexed Soviet planners in the Second World War. Typically, the initial breakthrough would be created through attacks in one or two echelons, followed by a mobile group (usually a tank formation) which pass through the breach to attack the enemy’s depth. The aim was that the initial attack should be so successful that this exploitation force could glide cleanly through without suffering any delay or loss of momentum fighting through the remnants of enemy defenses.

This was a tricky balancing question. It took lots of trial and error to discover that forward echelons had to be much stronger than the mobile group with comparatively more tanks, while restricting their breakthroughs to a fairly narrow frontage. There was also the question of force composition: the Soviets consistently underestimated the quantity of artillery needed both to effect a penetration and to form a suitable mobile group.

The Limiting Factor

But the biggest problem plaguing the Soviets was straightforward material quantity. Only in the later years of the war did they have sufficient equipment to accomplish the tasks they set for themselves. Anticipating future material requirements in periods of rapid technological change is always difficult. Armies at the beginning of World War I scrambled to increase the number of machine guns and heavy artillery at the front. German divisions underwent a 12-fold increase in the number of machine guns between 1914 and 1918, while the French army increased its total heavy artillery by more than eight times.

The same phenomenon is evident today. Fighting in Ukraine has revealed just how woefully inadequate NATO assumptions were regarding drone requirements, and the rate of ongoing change will no doubt invalidate current estimates by the time of the next big war (to say nothing of the needs of different operating environments). But while both sides in Ukraine have experimented with many different permutations of force structure, force structure itself has been no substitute for quality and quantity of drones. To put it more generally:

Material capacity is the limiting factor, not force structure.

Designing a unit around a specific function is pointless without the right equipment and personnel, whereas a military with the right equipment and personnel can find many workable. Procurement is slow and difficult. It is easy to stand up a drone brigades, but difficult to supply the millions of drones at all echelons needed to fight a major war. It is easy to optimize a Marine Littoral Regiment for a specific problem set, but hard to acquire the missiles, radars, and surface connectors necessary to deny access in the Western Pacific.

Implementing Force

After basic material requirements, there is another fundamental question: how to employ them. Developing effective tactics and techniques for new weapons requires lots of experimentation, which in turn demands a certain flexibility in command relationships.

To use the 1940 example cited in the MWI article, German Panzer divisions went through many iterations in the prewar years. These divisions were not designed for a single specific purpose, however, but rather to make the most effective use of the tools at their disposal. Tanks of the interwar years were imagined in a variety of roles—trench breakers, infantry support vehicles, or as a type of substitute cavalry. Early iterations of the Panzer division envisioned closer cooperation between tanks and infantry, before experimentation showed that radios and motorized supporting units could allow them to maneuver independently.

These general-purpose units were the solid building blocks out of which larger operations were constructed. 1st Panzer Division, which formed the tip of the spear at Sedan, was not a purpose-built breakthrough unit, but a standard Panzer division reinforced with the requisite infantry, engineers, and artillery to break across the Meuse. It and its sister divisions then continued to develop the exploitation across northern France—their role was not limited to penetration.

So it is with any operation. Every scenario is always unique, and the devil is always in the details. Trying to front-load the planning process by embedding likely scenarios into force structure only ties their hands, and is no substitute for well-trained, well-equipped, versatile units.

Turning an Obstacle into an Advantage

A certain adaptability in command relationships are therefore paramount not just for experimenting with new tactics, but also in the actual conduct of operations. This is a tremendous challenge for all militaries, but presents a great opportunity for those which are quick to embrace it. Interoperable systems, common doctrine across services and arms, and a flexible command culture could prove far more important than attempts to tackle the problem from too far out.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Please like and share if you enjoyed, it helps more people find this. You can also support with a paid subscription, supporters receive the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529 and get access to exclusive pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist, in paperback or Kindle format.

Yes this doctrine looks suspiciously like “yeah but we would succeed where they failed” backseat quarterbacking. There are so many brittle assumptions in their 4-division 4-phase model. And if any assumption breaks you have the wrong units in the wrong place at the wrong time with the wrong equipment, wrong training and wrong doctrine.

We’re short materials and logistics officers, over strength and overstaffed combat arms … and prithee over theories-d and over PPT and over published;

solution: put down the lyre of Apollo and pick up the hammer and anvil of Vulcan. In plain words go into logistics AND industry - industry is also short people. If you want to remain in uniform get 3D printers aka Additive Manufacturing to print all those motors and other short parts, or manufacture drones at your level. DLA has approved libraries for additive manufacturing parts (3D printing) and the drones are now munitions and resources pushed along with approval to unit level- other units already doing same in Italy (173d).

>Think of what a Bullet on the x_ER that makes<

If you can’t fight, BUILD IT until you can…

Link to DLA additive manufacturing below. ⬇️