Against Abstraction: Military Theory and Clarity of Thought

It is difficult to appreciate just how much Western—especially American—military thinking is pervaded with abstraction. So many common doctrinal terms are entwined with theoretical concepts that it is easy to inadvertently make some theoretical claim about the dynamics of warfare, either directly or indirectly.

Examples abound. A term like “center of gravity” does not just describe an aspect of a combatant’s system, but implicitly posits a single and specific source of strength that can be attacked. Maneuver theory builds upon this, elevating “maneuver” from physical movement to a position of advantage into a more abstract sort of action against the enemy’s center of gravity.

A number of other theories and doctrines have created elaborate theoretical constructs with terminologies to match: effects-based operations, network-centric warfare, and so forth. Less formally, John Boyd’s OODA loop, with its highly theoretical (and highly debatable) understanding of the dynamics of combat, has worked its way into the common lexicon.

By overloading common doctrinal terms with intellectual scaffolding, the effect has been more to obscure than to clarify. In all these cases, the theory itself is a matter of ongoing debate; we do not need to rehash those extensive arguments here, except to note that invoking them is liable to provoke a theoretical disagreement that distracts from the matter at hand. And even when two people largely agree on the underlying theory, they will often fiercely disagree over how those abstract concepts apply to reality

Anyone who has taken part in enough center-of-gravity analyses can readily attest to this. In that particular case, the doctrinal definition tries to render a question of judgment—what the focus of friendly efforts should be—into a matter of objective fact (more on this in a bit). More generally, excessive abstraction negates the very purpose of doctrinal terminology, which is to provide a commonly understood vocabulary for describing reality.

The Soviet Shadow

It was not always so. Doctrine up until the 1980s was far less bound up in theory. This is visible in the earliest expositions of AirLand Battle, the most elaborate doctrine of that era. Designed to defeat Soviet tank armies rolling across the North European Plain, it proposed an elaborate scheme to contain, isolate, and defeat them, using language that was remarkably concrete and straightforward. This changed in 1986, when AirLand Battle was formally made US Army doctrine with an updated version of FM 100-5 Operations, which introduced “center of gravity” into US doctrine. The Marine Corps followed three years later with FMFM-1, which articulated its own version of maneuver warfare.

The groundwork had already been laid even before these doctrines were published. Much of the growing interest in military theory was a product of late-Cold War paranoia, when fears of Soviet armor doctrine spurred a serious study of their military thought. American officers were much influenced by what they found, and began adopting the Soviet concept of an operational level of war in the 1970s—made formal doctrine with the 1982 version of FM 100-5.

Cognitive Capture

The official adoption of the “operational” was partly influenced by a 1980 paper by Edward Luttwak, which argued that the American military establishment suffered from a conceptual void. Failures to win decisive victories in Vietnam or Korea and the incremental progress in the European theater of WWII were said to spring not from material or organizational constraints, but rather from an intellectual misapprehension of the space between tactics and strategy.

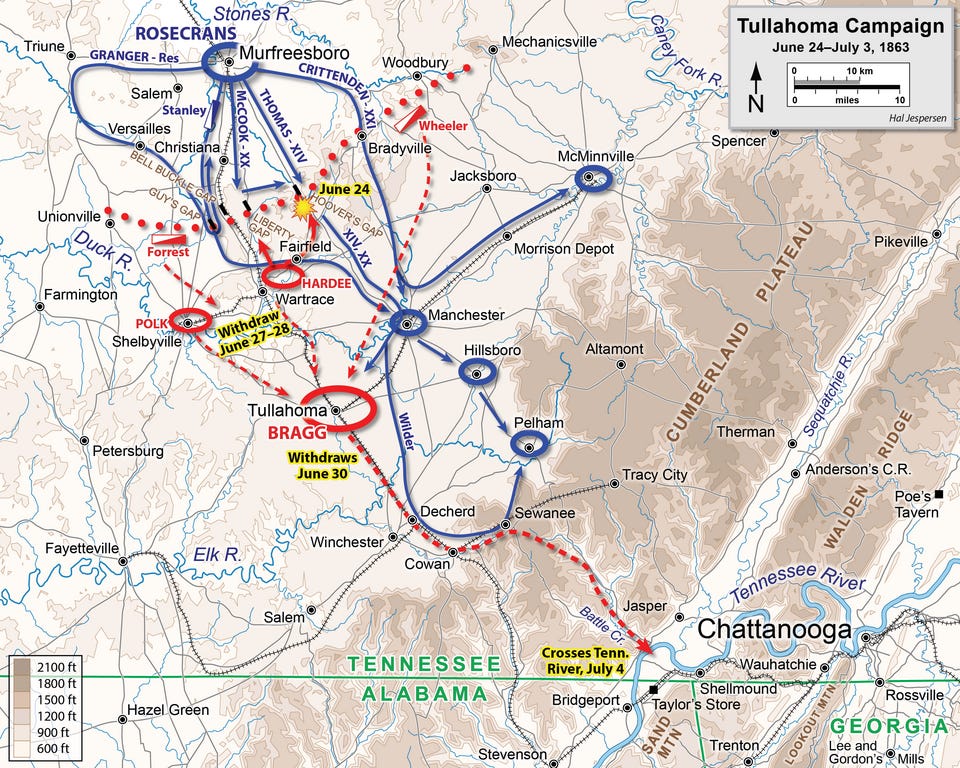

This argument encapsulates two errors which were shared by military thinkers more broadly. The first is a misunderstanding of the semantic shift that “strategy” had undergone. The word originally denoted just the maneuvers of a campaign—what we now call the operational—but expanded to encompass the entirety of the war effort. Later theorists imagined that operational art only “emerged” from between tactics and strategy at the end of the 19th century (a misunderstanding that originated with the Soviets themselves). In truth, we see “strategy” used during the American Civil War to refer to precisely those types of sweeping operational maneuvers that Luttwak insisted were lacking in American military art.

This points to the second, more serious, error: placing too much importance on intellectual frameworks. The reason that operational maneuver was not always exercised to its fullest potential in WWII had more to do with other factors: material constraints, risk calculation, overriding strategic priorities, etc. Commanders were aware of the possibility of more ambitious operations, and sometimes even entertained them, but decided that the benefits were not worth the costs (it should also be noted that those exceptional instances of operational maneuver that were undertaken didn’t always accomplish what they claimed).

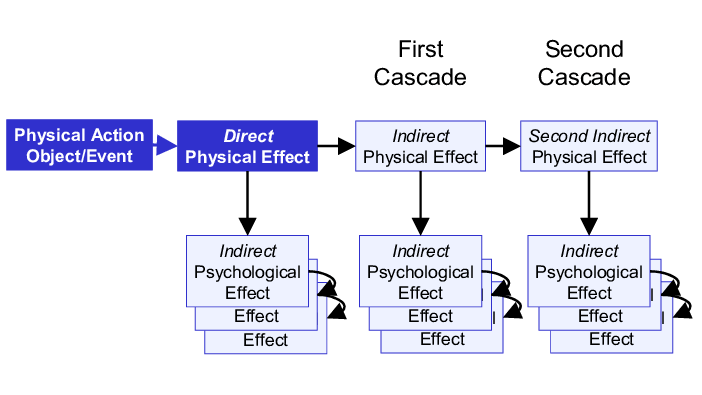

This focus on the mental aspects of warfare was part of the spirit of the age. This was around the time when John Boyd was giving lectures on his theory of decision cycles—the OODA loop—which singled out mental processes as the primary driver of the dynamics of combat. This later formed a core argument in support of network-centric warfare, a doctrine that advocated for tighter informational networks to connect sensors, weapons, and commanders.

In 1997, Israeli general Shimon Naveh published In Pursuit of Military Excellence: The Evolution of Operational Theory, which claimed to apply general systems theory to military operations. The book was a work of intellectual fraud which even plagiarized entire sets of endnotes.1 Happily, Naveh’s writing was so contorted that few even claim to have read him, and very little military theory since has approached his level of obscurantism; but it does seem to have popularized two buzzwords: “cognitive” and “systems thinking”.

Both terms proved popular among network-centric advocates (although the theory itself predated Naveh’s book), and the “cognitive domain” quickly became unofficial doctrine in the military establishment at large. It even worked its way into the current joint doctrine, which defines operational art as a “cognitive approach”—a gross reworking of an existing term that adds nothing of value.

The German School

Abstract concepts and excessive theorizing are not entirely new problems. Our use of the words “tactics” and “strategy” comes from an 18th-century milieu which loved applying classical terms to contemporary warfare, often to the detriment of clear thought. Jomini was notorious for imputing an elaborate system to Napoleon. Clausewitz himself used “center of gravity” in a more abstract sense, applying his original concept—a straightforwardly physical metaphor for large troop concentrations—more generally to such things as popular will or alliances (it is worth noting that he never finished reworking these sections of On War).

Given the high esteem which Clausewitz enjoyed in Prussia, it comes as something of a surprise how decidedly anti-theoretical that military tradition was. German officers made little use of abstract concepts, writing more about the practical aspects of training, maneuvers, and combat—their perspective could be summarized by Moltke’s description of strategy as “a system of expedients”. Their interest in Clausewitz lay more in the substance of his arguments than for his theoretical elaborations.

It is telling how they refashioned many of his terms to suit their own ends. Their use of the word Schwerpunkt (center of gravity) is a good illustration. All the way through World War II, German officers viewed it in very concrete terms: the Schwerpunkt was simply the main effort, where the most forces were naturally concentrated. Where a commander should place his center of gravity was a matter of judgment, but its actual identity was a straightforward matter of observable fact (in complete contrast to current understandings of the term).

The genesis of the operational level is another example. The concept of strategy was always somewhat open-ended at the top—from its adoption in the 18th century, some writers extended its bounds to the entire war effort—but its main focus was emphatically on the maneuvers of a single army in a single theater. Writing in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, when a single decisive campaign was usually enough to decide the entire war, Clausewitz redefined strategy as the use of tactics to win the entire war (although his actual usage did not necessarily reflect that definition).

This posed some awkwardness for later officers and theorists. The term straddled a yawning gap between the highest-order decision-making in a war and the much more limited maneuvers of a single field army—already becoming apparent after the Franco-Prussian War, itself a rapid war of just one campaign. In the following decades, German officers used Clausewitz’s definition of strategy to apply to the overall war effort, while pragmatically adopting the word operativ—which became operational in English—to maneuvers in the field. Terminology followed needs, with theory trailing distantly, if at all.

Form and Substance

Imperial Germany’s circumstances were very different from the present. No NATO country has fought a full-scale, long-duration war since Korea, allowing the weeds to grow thick. For all that, the theorizers often get much right. The maneuverist school injected much-needed vigor into the US military by arguing for speed, initiative, and decentralized control, even if their theoretical edifice was built on shaky foundations. Network-centric partisans were completely correct in their advocacy for more integration of information systems, as recent experience has shown.

This only goes to show that theoretical constructs are completely unnecessary in the first place. At best, they waste huge amounts of time and energy on fruitless debate. At worst, they lead to eventual disasters such as Ukraine suffered in summer 2023, when on American advice they attempted the sorts of bold maneuvers that material reality simply precluded.

The Ukraine War has done much to bring people back to earth. It is once more respectable to speak of attrition as a viable strategy, contra maneuverist dogma. Commentary focuses more on the concrete than the abstract (even using more direct terms like “axis” and “front” that had long fallen out of fashion). Completely separately, there has been growing pushback against the worst excesses of theory.

Institutional inertia is nonetheless strong, and it is easy to fall back on bad habits. I propose a few rules of thumb:

Doctrinal terms should be straightforward and objective, not intertwined with theoretical concepts. Their purpose is to establish a common basis for discussion, they should not provoke debate all on their own.

“Concepts” as a whole should be treated with suspicion outside of narrow bounds. Sophisticated thought grows from thorough knowledge and careful analysis, not appeals to abstraction.

The degree to which higher-order concepts are even practicable comes from competence at lower levels—“brilliance in the basics” is a good guideline, as always.

Thank you for reading the Bazaar of War. Most articles are free for all to read, but a subscription option is available to all who wish to support. Subscribers receive a pdf of the critical edition of the classic The Art of War in Italy: 1494-1529, and will have exclusive access to occasional pieces.

You can also support by purchasing Saladin the Strategist in paperback or Kindle format.

Hilariously, he equates the dynamics of a non-linear system with the evolution from linear tactics to deployments in depth. The one sense of “non-linear” refers to complex relationships between the variables governing a system, while the other simply means “not arranged in a line”.

The fall-off noted after the Cold War, is telling of the need for a concrete adversary. Abstraction runs wild as a result. Perhaps, the rise of China will present a chance to undo this trend.

This article is recommended as it opens up the discussion on how NATO should adapt for a hypothetical conflict with Russia. Is its current tactical-operational doctrine still relevant? Will a future conflict scenario resemble the Ukrainian theater of operations? Is maneuver warfare, as attempted in the summer of 2023, still a viable option? In short, an excellent article for fostering strategic and operational thinking.